by Gideon Marcus

I have a friend, a gentle and curious soul, whose hobby is to procure aged military rations and try them out. Though they are often long past their expiration date, nevertheless, Steve tucks into this hoary stuff like it's haute cuisine. C-Rats from the last war, rations from the Great War — why, I once even saw him sample Bully Beef from the Boer War. He's essentially indulging in culinary Russian Roulette. Like, crazy right?

This month, I was Steve, and the November 1963 Analog was the bullet in the revolver.

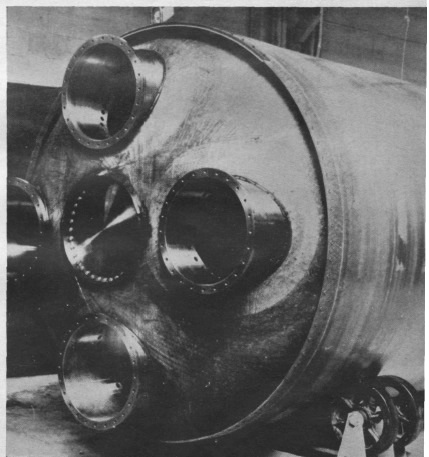

Seagoing "Space" Ships, by Charles Layng

The non-fiction piece this month is about the pair of blue-ocean tracking ships that were custom built for the Air Force. I'd read about them in Aviation Weekly so I was keen to learn more. Sadly, Mr. Layng takes a potentially fascinating topic and buries it under dull technical minutiae. It's not enough that an article tell you how something works; it must tell you why it's important. Two stars.

Take the Reason Prisoner, by John J. McGuire

Prisons in the future are run by the military, and convicts have short sentences. Rather than while away their lives for nickels and dimes at Joliet, instead they are hypno-conditioned with drugs and psychotherapy such that they can be released quickly.

At least, I think that's the premise. The story features one General Bennington on the day of his appointment to warden at Duncannon Processing Prison, where he is eager to address the recidivism rate. His efforts are immediately stymied when a fresh batch of 35 convicts riots and seizes control of the facility, their conditioning subverted by a guard on the take. One prisoner, a psychopathic serial killer with a taste for flashy murder, wends a bloody course through Harrisburg, Pennsylvania before being caught.

What's never addressed is why the conditioning is not effective treatment when the process is administered properly, nor even how the whole setup came to be or is supposed to work. Moreover, there is a glib tone of authoritarianism throughout the piece, with the end degenerating into a paean for the death penalty. It's a difficult read, to boot, sketchy and confusing. I think the author was trying for "experimental."

In fact, John J. McGuire is a marginal writer, having published little, and less on his own (most was in collaboration with H. Beam Piper). This is a common theme with the authors running through this issue, as you'll see.

One star.

Pleasant Journey, by Richard F. Thieme

What if a simple chair-and-helmet contraption could send you into a private nirvana, a perfectly real simulacrum of a personal paradise? Imagine the potential for addiction, the detrimental effect on society.

Thieme, a brand new author, affords us a vivid glimpse at the experience of using a such a machine, though in just two bedsheet pages, he can't expand much upon the consequences. Three stars.

Interview, by Frank A. Javor

Javor's fourth story, Interview is another vignette, an "if this goes on" piece extrapolating current trends in news reporting in which the crisis is often exaggerated (if not outright manufactured) for dramatic value. Three stars.

Where I Wasn't Going (Part 2 of 2), by Walt Richmond and Leigh Richmond

I decided to give this serial a second chance. After all — maybe it just had a rough start. I nearly fell asleep just during the summary, a technical snooze-fest. The story, itself, is about the romp that ensues after a couple of space-station based scientists develop a reactionless drive, the test of which accidentally destroys Thule Air Force Base in Greenland.

Sound like a comedy? It's not supposed to be. Unless you find bad dialogue, bigoted caricature characters, and sheer dullness funny. And yes, this is the first published creation of the Richmonds. One star.

Problem of Command, by Christopher Anvil

Last up is a piece written to order for Editor Campbell in which an ambitious colonel throws away his chance at Brigadier's star when he argues against a plan, advanced by his boss, to destroy the Soviet Union with a wonder weapon. Turns out, of course, that his boss and his boss' boss were in collusion to find an officer with the gumption to stand up to their superior. And for bonus, it appears the brave-hearted General-to-be will win his boss' boss' daughter in the bargain for his daring.

Two stars. Even if the plot is laughable, the story is written in English. Anvil, by the way, is the only experienced author in the issue.

That squishy sound you hear is my collecting brain tissue back into my skull. At 1.8 stars, the November 1963 issue of Analog is the worst issue of the magazine since it changed its name from Astounding. Worse yet, this has been a lousy month for magazines in general. Fantastic rated a dismal 2.2 while IF got just 2.3 stars. Amazing's and World of Tomorrow's 2.8s are no great shakes, and frankly, I'd rate Amazing's "good" stories lower than John Boston did. As for WoT, the best part of that mag is Dick's All we Marsmen, and that may not appeal to all of you.

Only New Worlds (3.2) and F&SF (3.6) broke the 3-star barrier, the latter also containing my favorite story of the month: Eight O'Clock in the Morning (Fred Saberhagen's Goodlife in WoT was a close second.) Woman authors composed just two out of thirty nine pieces.

So why do I keep doing this? Why do I tempt fate every month? I'm starting to wonder that, myself. Hopefully, it's for your amusement and edification (I suffer so you don't have to). And there is always the junkie's hope that I'll find a really good fix that lasts.

Here's hoping…

![[November 1, 1963] Bitter taste (November 1963 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631101cover-451x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1963] Worse than it looks (October 1963 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631001cover-649x372.jpg)

![[Sep. 1, 1963] How to Fail at Writing by not Really Trying (September 1963 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630831cover-672x372.jpg)