by John Boston

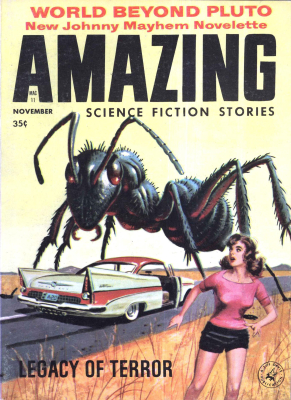

Last month, I asked: can they keep it up? Amazing’s marked increase in quality, that is. Well, no, not this month anyway.

The May 1962 Amazing labors under a large handicap: half of it is given over to The Airlords of Han by Philip Francis Nowlan, the second Buck Rogers novella, reprinted from the March 1929 issue. It starts with a synopsis by Anthony (the Buck has not yet passed) of his emergence from 500 years of suspended animation to discover an America dominated by "the Airlords of Han, fierce Mongolians, who . . . had in their blood a taint not of this earth." But now, the Americans hiding in the woods have mostly retaken the continent while the Han remain huddled in their cities; “the positions of the Yellow and the White Races in America had been reversed.” So it’s Yellow Peril time again!

The good news: Nowlan is quite a facile writer for his time, his style livelier and less stilted than in many of these alleged Classic Reprints. But the substance often gets tedious fast, consisting in good part of catalogues of military tactics, weapons, and the uniforms of the various Gangs (led by Bosses) of rusticated Americans. Here Anthony describes a weapon he designed:

It was a long-gun which I had adapted for bayonet tactics such as American troops used in the First World War, in the Twentieth Century. It was about the length of the ancient rifle, and was fitted with a short knife bayonet. The stock, however, was replaced by a narrow ax-blade and a spike. It had two hand-guards also. It was fired from the waist position.

“In hand-to-hand work one lunged with the bayonet in a vicious, swinging up-thrust, following through with an up-thrust of the ax-blade as one rushed in on one’s opponent, and then a down-thrust of the butt-spike, developing into a down-slice of the bayonet, and a final upward jerk of the bayonet at the throat and chin with a shortened grip on the barrel, which had been allowed to slide through the hands at the completion of the down-slice.”

One wonders if Nowlan might better have been employed writing technical manuals. There are similarly detailed, and much longer, discussions of the opposing forces’ technology—chapter IV is titled “Han Electrono-Science” and V is “American Ultronic Science,” three to four pages each. Even when something actually begins to happen (as Anthony puts it beginning chapter VI, “But to return to my narrative. . .”), Nowlan quickly reverts to verbose digression. When Anthony is captured by the Han, Nowlan spends nearly a page on their physical appearance and their uniforms and gear. He also sociologizes for many pages describing the decadent Han society, which is ultimately dominated by the repairmen, who control the machines on which everyone depends—and no one wants to tangle with their “Yun-Yun.” Later, there is considerably more action, but it too becomes tedious—pages of slaughter and destruction abetted by escalating super-science.

Admittedly, Nowlan is more progressive concerning the role of women than most writers of his era. While his precis of Han society contains a rather bigoted description of women’s place, among the Americans, “men and girls” (as the author puts it) seem more or less equal, both participating in combat. The girls appear to relish their roles, as witness Wilma, Anthony’s wife:

“Like a shriek of the Valkyrie, Wilma’s battle cry rang in my ear as she, too, shot herself like a rocket at a red-coated figure. . . . [Digression while Anthony kills a Han]

“And from the corner of my eye I saw Wilma bury her bayonet in her opponents, screaming in ecstatic joy.”

Despite the racist theme, with passing references to “evil yellow faces” and the “morally degraded race,” plus a disquisition on how the Han lack souls, Nowlan ultimately tries to have it both ways. After the genocide of the Hans, Anthony travels the world and finds everybody pretty nice—“the noble brown-skinned Caucasians of India, the sturdy Balkanites of Southern Europe, [and] the simple, spiritual Blacks of Africa, today one of the leading races of the world, although in the Twentieth Century we regarded them as inferior.” It was just those damn Hans, who weren’t really human but sprang up when extraterrestrials raped the Tibetans.

Sorry, it doesn’t wash. It’s as if D.W. Griffith had ended Birth of a Nation, his famous movie glorifying the Ku Klux Klan, with a placard saying “Just kidding, folks.”

In this time of the Freedom Riders and the sit-ins—but also the time when I hear vile racial slurs virtually daily in this near-Southern small town—who needs this crap? I know, it’s historically important. But so is, say, James Buchanan, and I don’t hear anyone clamoring to bring him back.

One star, and a big “Bah, humbug.”

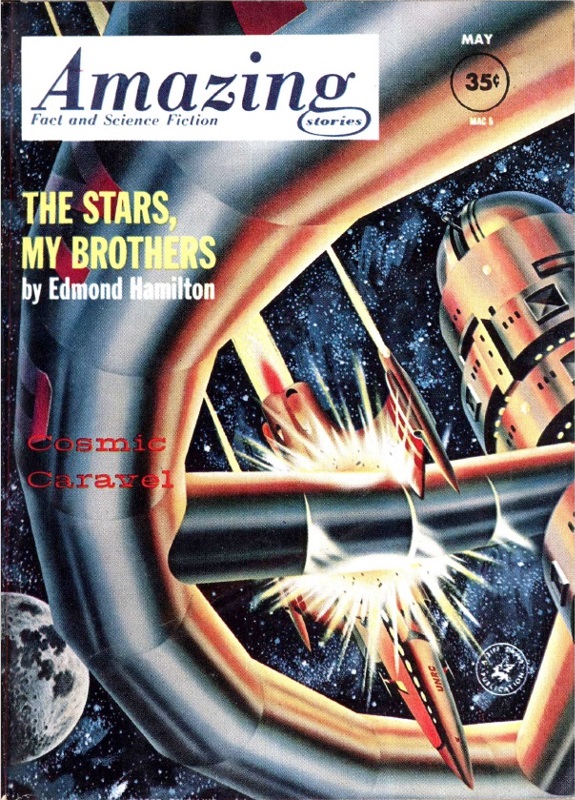

The lead story is Edmond Hamilton’s longish novelet The Stars, My Brothers, which could have been titled Across the Galaxy in a Bad Mood. Scientist Reed Kieran is killed in a space accident, but finds himself a century later waking up in a starship en route to Altair . He is surprisingly un-delighted at receiving a new life in a new age, and it doesn’t help that his resurrectors are not very nice and don’t want to tell him much. Eventually he learns that they are from the Humanity Party, which believes that “humans should not be ruled by non-humans,” and they have illicitly revived him to be a symbol in a campaign against the planet Sako, where a more intelligent and civilized reptilian species dominates a human population that is “very low in the scale of civilization.” Shaking with rage, Kieran declares, “I have no more use for the idea of the innate sacred superiority of one species over another than I had for that of one kind of man over another.” Now that’s a nice thought, especially after The Airlords of Han.

They land on Sako and are promptly attacked by the primitive humans. Treks and chases ensue and eventually we meet the reptilians, who it turns out are managing the local humans reasonably humanely, like we (sometimes) manage animal populations. The whole thing is as unconvincing as it is didactic, and Kieran’s noble sentiments can’t redeem it. There’s a romantic subtheme that is as sour and implausible as the rest of it. There’s also a conspicuous failure of craft at the beginning: though the actual story doesn’t start until Kieran’s resurrection, there are four and a half pages of mostly irrelevant background—a tenth of the total length—about Kieran’s previous life and how he came to be left dead in his spacesuit, including such data as his street address in Midland Springs, Ohio. One may wonder whether this story was cut down—but not enough or not carefully—from a novel-length piece Hamilton started for one of his now-defunct ‘50s markets. Anyway, two stars mitigated by the author’s good intentions.

John Jakes’s The Protector is a purposefully heavy-handed short story about a guy who after the nuclear war serves as the “protector” for a small town of survivors, or so it seems, and to say anything more would give the whole thing away. It’s effectively oppressive but there’s not much story left when the style and attitude dissipate. Two stars.

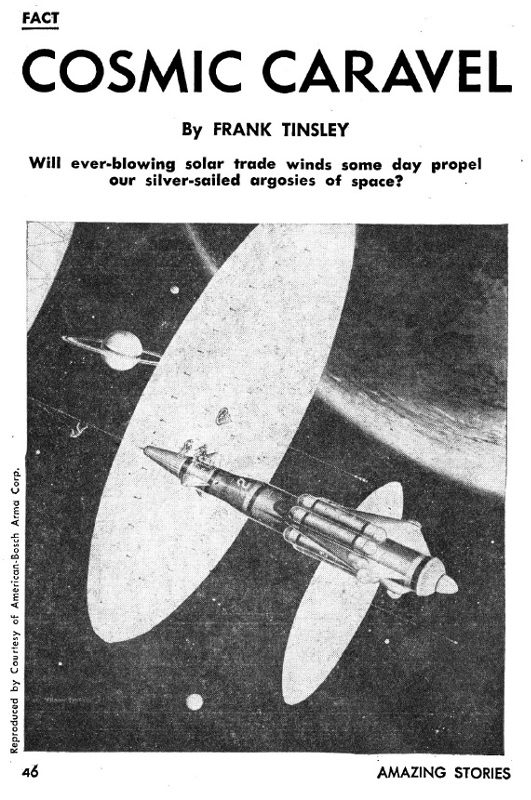

Frank Tinsley is back with a science article, Cosmic Caravel, concerning spaceships which may be constructed in orbit and propelled by gigantic sails to catch the “Solar Wind” or “Photon Breeze.” Interesting idea, but the usual dull rendering from Tinsley. Two stars.

Benedict Breadfruit. That is all.

[Yikes! Months like this make me feel like a harsh taskmaster. Let's hear a round of applause for poor young Boston, who suffered so. I am grateful, in particular, for his taking on the Buck Rogers tale. Better luck next time, Master John! (Ed.)]