by John Boston

Off Days

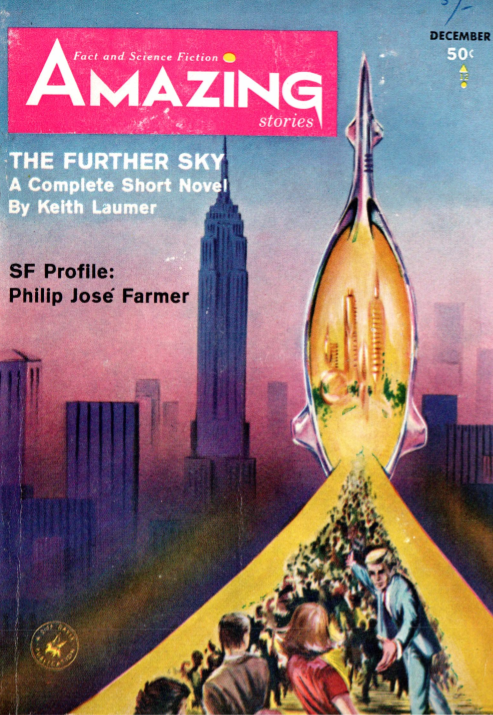

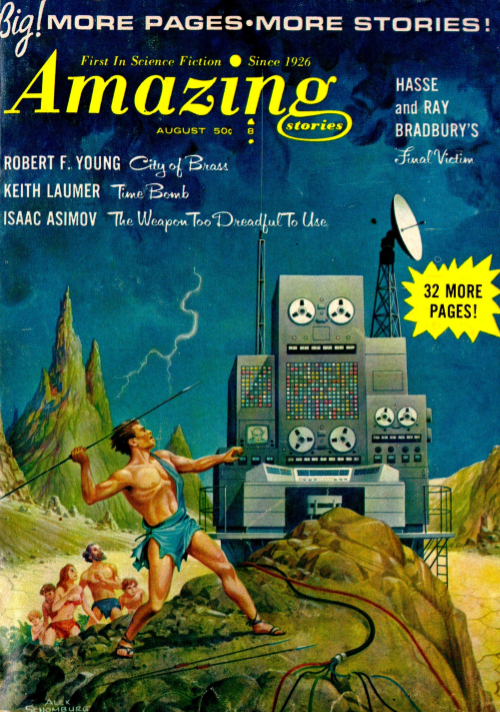

The December Amazing, boasting Cordwainer Smith, Murray Leinster, Edmond Hamilton, Robert Sheckley, and Chad Oliver, looks promising despite the hideous front cover by Hector Castellon. Unfortunately, the unifying theme of the issue is Off Days of Big Names.

by Hector Castellon

But first, let’s survey the terrain. The Smith and Leinster stories are new, and informed rumor has it they are the first purchases of the new editor after the exhaustion of Cele Lalli’s leavings. They are long, so the three reprints make up a smaller proportion of the magazine than in the previous issue, less than half of the total page count. Almost all the the issue’s contents are fiction. The editorial is one page, as is the letter column, and that’s it: no article, no book reviews.

The editorial by Joseph Ross cocks a fairly vapid snook at outside critics of SF, most recent example being Kurt Vonnegut, who isn’t entirely outside, and the letter column—both the letters and the editor’s responses—are calculated to cheer on the magazine and celebrate the true pulp quill, with a sideswipe at the previous editor’s attempts at something a little more elevated.

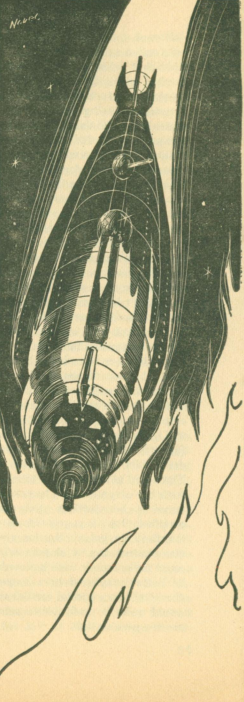

Killer Ship (Part 2 of 2), by Murray Leinster

The longest item is the conclusion of Murray Leinster’s serial Killer Ship, which inhabits the subgenre of Reactionary Science Fiction. This is not a political designation, but a description of stories that suggest—nay, insist—that the future will, conveniently for the lazy reader and writer, not be much different from the past. This one began last issue with: “He came of a long line of ship-captains, which probably explains the whole matter.”

by Norman Nodel

There follows a genealogy of the protagonist Captain Trent’s space- and sea-faring ancestors back to the eighteenth century, followed by several paragraphs about the similarity between the dangers of space travel and those of eighteenth-century sea voyaging, complete with Trent’s ancestor sailing into port with the hanged bodies of pirates swinging from the yardarms. There’s no indication of what Trent knows or how he has been influenced by these ancestors’ doings, so how his lineage “explains the whole matter” is a bit murky.

A couple of pages later, after it is disclosed that the ship-owners who have hired Captain Trent for a trading voyage in pirate-infested waters, er, space, would be just as happy if he gets pirated so they can collect the insurance: “It didn’t bother him. He came of a long line of ship-captains, and others had accepted similar commands in their time.”

Six pages further on, when it appears Trent’s ship has spotted a lurking pirate: “The report of a reading on the drive-detector was equivalent to a bellowed ‘Sail ho!’ from a sailing brig’s crosstrees. Trent’s painstaking use of signal-analysis instruments was equal to his ancestor’s going aloft to use his telescope on a minute speck at the horizon. What might follow could continue to duplicate in utterly changed conditions what had happened in simpler times, in sailing-ship days.”

Later still: “The arrival of the Yarrow in port on Sira was not too much unlike the arrival of a much earlier Captain Trent at a seaport on Earth in the eighteenth century.” I will spare you the extensive elaboration. And I can’t resist one more, towards the end as the Captain and his men are mustering for the final battle: “When they gathered, crowding, to get into the Yarrow’s spaceboats, the feel of things was curiously like a forgotten incident in the life of a Captain Trent of the late eighteenth century.” (Again, spare the details.) There is no suggestion that the current Captain Trent is in any way aware of this incident. Hey, the author just said it’s forgotten!

At this point it is tempting to ask, Why bother? Why not just swing by the library and pick up a stack of old C.S. Forester novels, and take your eighteenth century straight?

Another conspicuous feature is its pervasive verbosity. Consider the following passage, right after the discovery that there’s another spaceship lying low very close. Trent throws a switch that turns on the signal-analyzing instruments and goes to work. Now:

“There was silence save for that small assortment of noises any ship makes while it is driving. It means that the ship is going somewhere, hence that it will eventually arrive somewhere. A ship in port with all operating devices cut off seems gruesomely dead. Few spacemen will stay aboard-ship in a spaceport. It is too still. The silence is too oppressive. They go aground and will do anything at all rather than loaf on a really silent ship. But there were all sorts of tiny noises assuring that the Yarrow was alive. The air apparatus hummed faintly. The temperature-control made small, unrelated sounds. Somewhere somebody off-watch had a tiny microtape player on, the Aldonian music too soft to be heard unless one listened especially for it.”

Next: “The signal-analyzer clicked.” Intermission over! Story starts up again!

And here’s another one, short but telling. Captain Trent and the captain of a pirate-bashed ship whose crew Trent has rescued are about to travel from one ship to the other. “The Yarrow’s bulk loomed up not forty feet away, but beneath and between the ships lay an unthinkable abyss. Stars shown up from between their feet. One could fall for millions of years and never cease to plummet through nothingness.” Then they snap on lines and are hauled across the 40 feet, sans plummeting or any actual risk or fear of it.

A little later (we’re up to page 29 of the October issue), there is a long description of the pirates repairing the damage to their ship that Captain Trent inflicted by ramming them. This is actually a nice vivid word-picture. But then:

“While this highly necessary work went on, the stars watched abstractedly. They were not interested. They were suns, with families of planets of their own; besides, some of them had comets and meteoric streams and asteroid belts to take up their attention. There was nothing really novel in mere mechanical repair-work some thousands of millions of miles away from even the nearest of them.”

And it goes on, and on, appearing everywhere like water seeping up through the floorboards of a flooding house. It’s enough to make a body wonder if paying by the word is really such a good policy.

Oh, yes, there is also a story here, fitfully visible through the padding and the constant eruptions of the eighteenth century. Trent takes on a job carrying a cargo through pirate territory, partly to make some money and party because he hates pirates. He has an encounter with some pirates, captures some of their crew, and rescues the boss’s daughter (boss meaning owner of the pirated spaceship, and also a planetary president). She thinks he’s the cat’s meow for rescuing her, and he sort of likes her too, but duty calls. Then everybody foolishly thinks it’s safe to travel again because Trent defeated this lot of pirates. The boss’s daughter gets kidnapped by pirates again. Trent cleverly figures out where she and the other hostages must be, goes there with his crew, confronts the pirates in their lair, rescues boss’s daughter again, wedding bells clearly to follow.

There are some clever plot twists along the hackneyed way, as one would expect from a guy who’s been at this for well over four decades. There are also characters, sort of. Captain Trent is the strong laconic guy who may have inner turmoil but keeps it to himself. Everybody else is essentially a cartoon, notably Trent’s crew, who play a big part in his success, and who are essentially a bunch of roughnecks the Captain has recruited from barroom brawls and who follow him because he’s a pretty good brawler too. Finally, there is the definitive happy ending: “This novel will be published in the winter by Ace Books under the title ‘SPACE CAPTAIN.’ ”

One star for both parts. That’s the average of two stars for smooth professionalism, and zero stars for polished vacuity; life’s too short to waste time on this.

On the Sand Planet, by Cordwainer Smith

All right, Henry, wheel that one out and release it to the next of kin. Who’s on the next slab? Oh, Cordwainer Smith. Sounds promising. Except . . .

On the Sand Planet seems to be the last in the Instrumentality series featuring one Casher O’Neill that began with On the Gem Planet and On the Storm Planet, with Three to a Given Star tangentially related. They were all published in Galaxy, to considerable praise from the Traveler. But . . . if the others appeared in Galaxy, what is this one doing here at the bottom of the market? Unfortunately, suspicions confirmed.

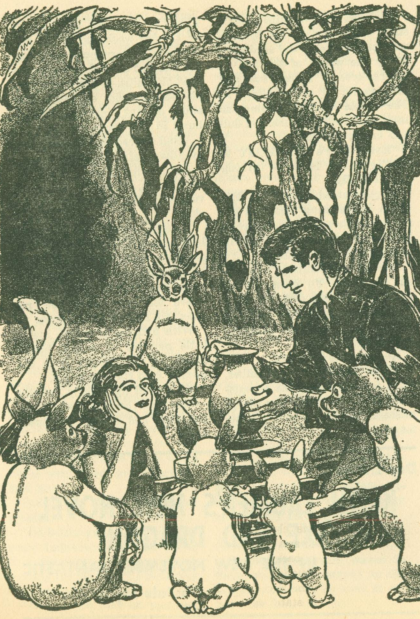

by Jack Gaughan

Casher O’Neill has been on a mission to relieve his home planet Mizzer of the tyrant Wedder, and to that end has circuitously toured the galaxy and has obtained various superpowers, apparently courtesy of T’ruth, an Underperson derived from a turtle. That’s all before this story opens. Now, he’s landing on Mizzer again, walks into town and into Wedder’s citadel, and using his superpowers, rearranges Wedder’s head and portions of his supporting anatomy, turning him into a pussycat. Metaphorically, I mean. While he’s at it, Casher restores the intelligence of an idiot child.

Now that Casher is done with his life’s work, he drops in on his mother, who has mixed feelings about him, and his daughter, who has her own life and would just as soon he went away. So he decides to go to the Ninth Nile (this city Kazeer is at the confluence of a whole lot of Niles, it seems), though he is warned he will need iron shoes for the volcanic glass.

At the Ninth Nile, Casher meets D’alma, an elderly dog-underperson and an old acquaintance, who accompanies him, first to the gaudy City of Hopeless Hope, where everyone seems to be engaged in the practice of one religion or another, and D’alma warns that they are “the ones who are so sure that they are right that they never will be right.” Then, to the place of the Jwinds, “the perfect ones,” who destroy intruders who don’t meet their high standards. But Casher, who contains multitudes in his enhanced cranium, is too much for them. On to Mortoval, where a gatekeeper lets them pass when Casher again musters his superpowers to invoke “old multitudes of crying throngs.” The gatekeeper asks, “How can I cope with you?”

“ ‘Make us us,’ said Casher firmly.

“ ‘Make you you,’ replied the machine. ‘Make you you. How can I make you you when I do not know who you are, when you flit like ghosts and you confuse my computers?’ ”

On to Kermesse Dorgueil, where D’alma warns “here we may lose our way because this is the place where all the happy things of this world come together, but where the man and the two pieces of wood never filter through,” and a guy named Howard explains, “We live well here, and we have a nice life, not like those two places across the river that stay away from life,” and they make no claim to perfection.

Here Casher encounters a woman, Celalta, who is dancing and singing, having resigned as a lady of the Instrumentality, and Casher recruits her as traveling companion by grabbing her wrist and not letting go. Also he introduces himself by telepathy-dump, including “the two pieces of wood, the image of a man in pain,” and tells her it’s “the call of the First Forbidden One and the Second Forbidden One and the Third Forbidden One.” The Trinity, like you’ve never seen them (or it) before! I guess.

Onward, past the Deep Dry Lake of the Damned Irene, resisting the temptation to lie down with the skeletons and die, to “the final source and the mystery, the Quel of the Thirteenth Nile,” where there are trees and caves, and fruits, melons, and grain growing, and evidence that other people used to live there, and also some surviving chickens running around. Celalta declares, “We’re Adam and Eve in a way. It’s not up to us to be given a god or to be given a faith. It’s up to us to find the power, and this is the quietest and last of the searching places.” Et cetera. Celalta says she’ll start the fire if O’Neill will go catch some chickens.

Well, this is pretty ridiculous. It’s obviously some sort of religious allegory, reminding me a little of my ill-fated glancing encounter with The Pilgrim’s Progress, told in an often sonorous style but a plain vocabulary, like a negotiation between the King James Bible and Fun with Dick and Jane (that’s not a complaint). But the point is a little elusive. I get that at least one of the two is thinking about Adam and Eve, since she says it straight out. But then what? Mr. Smith owes us one more story in the series, catching up with Casher and Celalta and their inevitable children after ten years or so in isolation, living on feral chickens roasted in a cave. But you know it won’t happen.

Two stars for this shaggy God epic. As exasperating follies go, it’s at least readable and amusing.

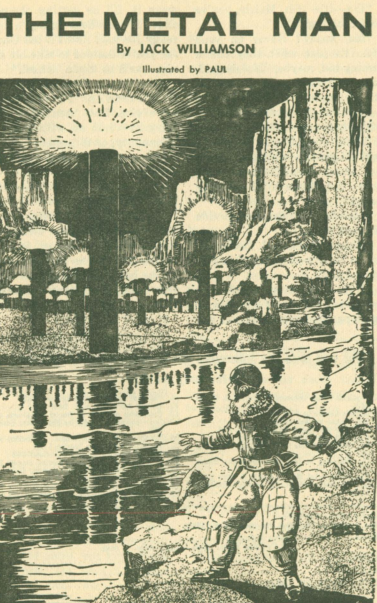

The Comet Doom, by Edmond Hamilton

The reprints are an exceedingly mixed bag. Surprisingly, the best is also the most archaic, Edmond Hamilton’s The Comet Doom, from the January 1928 Amazing. There’s a big green comet passing by, and it turns out it’s inhabited by atomic-powered metal beings with tentacles who used to have organic bodies but gave them up. These folks have about used up the comet’s resources and want to replenish their stores by carrying off a handy planet, ours to be precise. In fact they have just yanked the Earth out of its orbit. To further their scheme, they land on a lake island and snatch our heroes, Coburn and Hanley, and offer them metal bodies and immortality if they will help out in the liquidation of their species.

Hanley goes for it, Coburn escapes. About this time, Marlin—the story’s narrator—is passing by the island in a boat which is half-destroyed by the comet, swims to shore, and encounters Coburn, who recruits him to the human cause. They attack the cometeers and Coburn is killed, but the already-transplanted Hanley, in a final moment of human loyalty, destroys the machine that is steering Earth towards the comet, along with the comet-people present. Doom is foiled.

This one is reasonably readable, mostly done in a style that reflects close attention to H.G. Wells, with echoes of both The Star and The War of the Worlds, despite the pulpish plot. Two stars by today’s standards, probably a standout by those of its time.

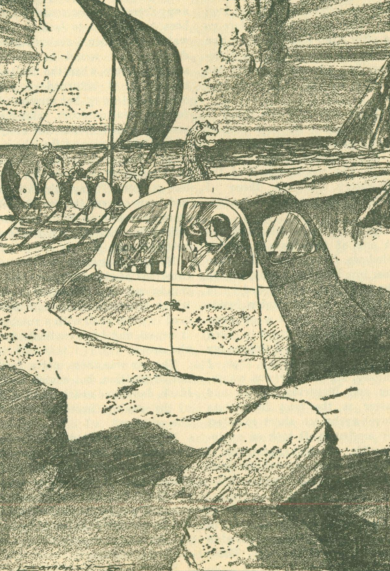

Restricted Area, by Robert Sheckley

The other reprints are from the brief high-budget, and relatively high-brow, flowering of the Ziff-Davis magazines during 1952 and 1953, immediately after the magazine went from pulp size to digest size. Robert Sheckley’s Restricted Area, from the June-July 1953 Amazing, is one of the slick but empty and cartoony pieces he produced in quantity at the beginning of his career, along with the more incisive ones.

by Greisha Dotzenko

Space explorers land on a paradisical planet–wonderful climate, no germs, no rocks, lots of colorful friendly animals ready to hang out and play, and a giant steel shaft ascending to the clouds. But after a while, the animals start to slow down and keel over. Connect the dots. Glib and facile, and the author knows it—this one hasn’t been in any of Sheckley’s multiple collections to date. Two stars, barely.

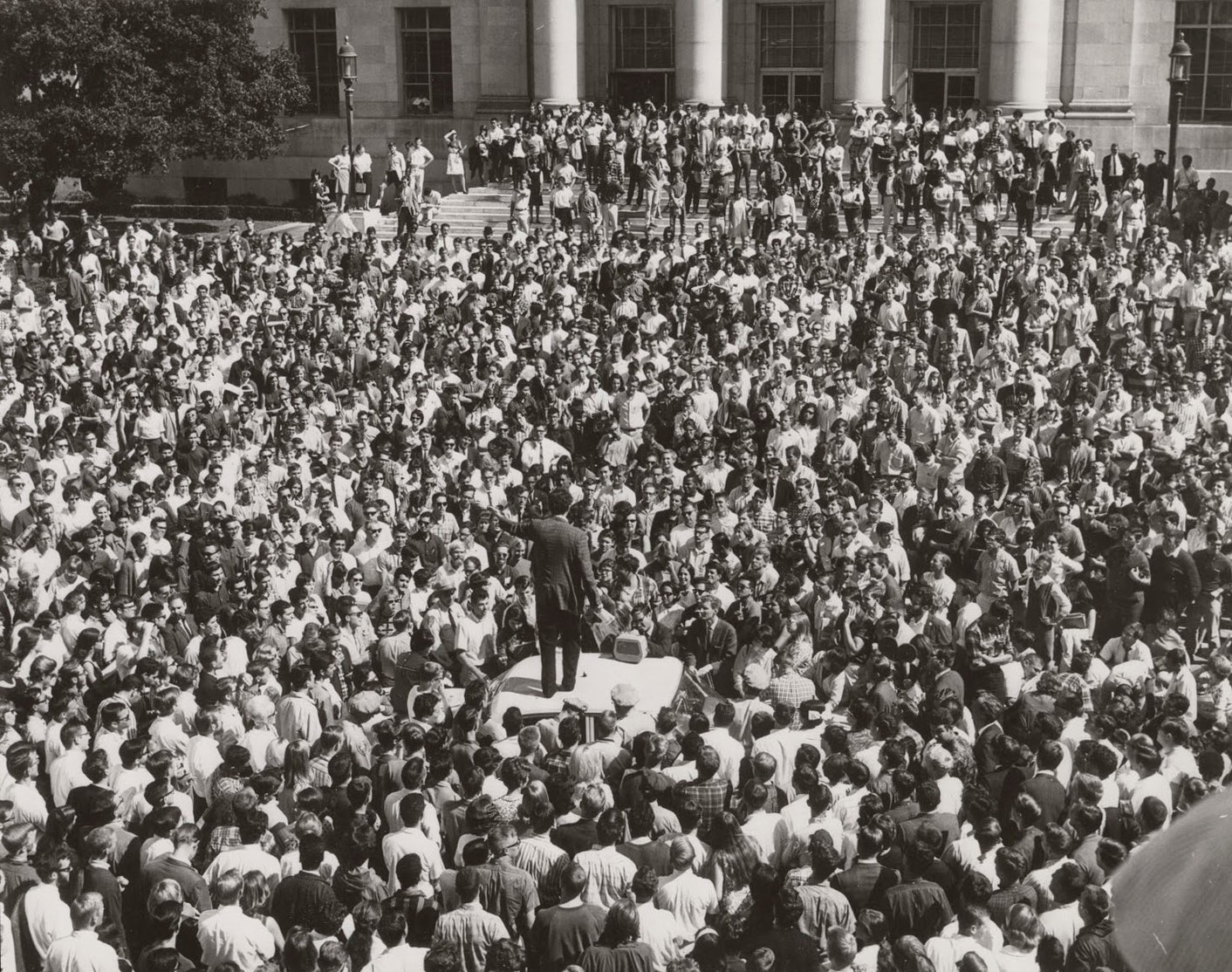

Final Exam, by Chad Oliver

by Ashman

Final Exam by the sometimes redoubtable Chad Oliver, from the November/December 1952 Fantastic, is also from what we might call the Intermission, or Respite, between the Ziff-Davis magazines’ last gasp as pulps and their monotonous and purposely formulaic low-budget era of the mid- and late 1950s. Like much of Oliver’s work, it reflects his anthropological bent (actually, a pretty straight-line bent—he’s become an anthropology professor at the University of Texas), but strikes an unusually sour note. Professor La Farge’s class in Advanced Martian History is on a field trip to see and condescend to some of the colorful and primitive surviving Martians, but the time for the Martians to turn the tables has arrived in this heavy-handed satire. Two stars, barely.

Summing Up

Well, a couple more hours we’ll never get back, and not much to show for it, except an eccentric misfire from a sometimes brilliant writer, and a tolerable relic of a bygone era. Next?

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[November 12, 1965] Doldrumming (December 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/amz-1265-cover-481x372.png)

![[September 12, 1965] So Far . . . Well, Fair (October 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/amz1065-cover-497x372.png)

![[July 14, 1965] The New Dispensation (August 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/amz0865-cover-500x372.png)

![[May 12, 1965] Da Capo (June 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/amz-0665-cover-391x372.png)

![[April 12, 1965] Not Long Before the End (May 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650412cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 12, 1965] Sic Transit (April 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/amz-0465-cover-672x372.png)

![[February 12, 1965] Mirabile Dictu, Sotto Voce (March 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/amz-0365-cover-524x372.png)

![[January 12, 1965] Last Minute Reprieve (the February 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/amz-0265-cover-1-521x372.png)

![[December 13, 1964] Save us from Yourselves (January 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/641213cover-480x372.jpg)

![[November 11, 1964] Unloading (December 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/amazing-6412-cover-493x372.png)