by John Boston

Adventures in Miscellany

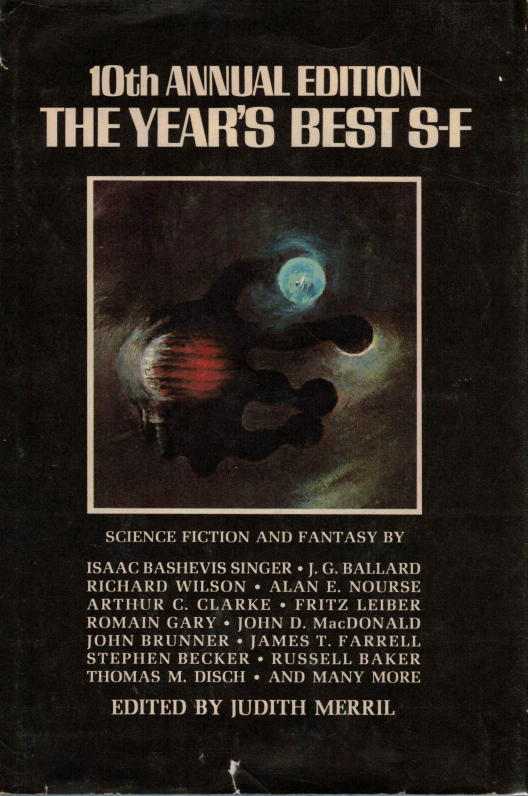

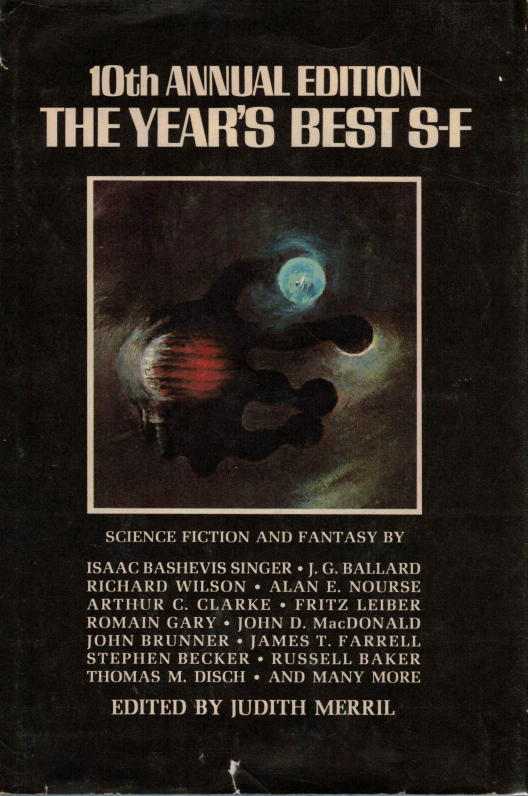

If it’s 1965, then it must be time for Judith Merril’s annual anthology from 1964. Admittedly, it’s pretty late in the year, which likely has to do with Merril’s change of publishers. After five years with Simon and Schuster, the new volume is from Delacorte Press, an imprint of Dell Publishing, which has published these anthologies in paperback since their inception in the mid-1950s. But here it is, styled 10th Annual Edition THE YEAR’S BEST SF, in time for the Christmas trade.

by G. Ziel

Over the years these anthologies have become larger. The growth is mostly in density; the page count has gone up a bit (400 pages this year), but the amount of text per page has grown remarkably from the early Gnome Press volumes.

The books have also grown much more miscellaneous. Their contents were initially drawn mostly from the familiar SF magazines, with a few other items from the well-known slick magazines. No more. This volume includes a gallimaufry of stories, quasi-stories, satirical essays, and what have you from sources as various as The Socialist Call, motive (sic—official magazine of the Methodist Student Movement), New Directions, and Cosmopolitan. (No cartoons this year, unlike last year’s book.)

This is all in service of Merril’s editorial philosophy of science fiction, which is that it doesn’t exist—or, at least, that there’s no difference between it and everything else, or at least something else. (See her soliloquy in the previous volume on what “S” and “F” really stand for, quoted in my previous comment on this series. The theme is continued here in her between-stories commentary, like a background noise you stop noticing after a while). You may find this view intellectually incoherent, but, like the feller (or Feller) said, by their fruits ye shall know them, and Merril makes a pretty interesting fruit salad. (Even if I have a bone to pick with parts of it.)

Unfortunately it’s hard to review a salad this big without sorting out its ingredients, which Merril might say defeats her purpose. Nonetheless, onwards. The book can only be discussed in layers.

Usual Suspects

The top layer, analytically speaking, is the first-class, or at least pretty good, SF and F from genre sources. The outstanding items here are J.G. Ballard’s The Terminal Beach from New Worlds and Roger Zelazny’s A Rose for Ecclesiastes from F&SF—and stop right there: Merril’s benign eclecticism is nowhere better illustrated than in the contrast between Ballard, driving avant-garde style and imagery and his preoccupation with psychological “inner space” into the genre’s brain like an ice pick, and Zelazny, rehabilitating the old-fashioned pseudo-other-wordly costume drama of the pulps with high style and intellectual decoration. Runners-up include Thomas Disch’s chilly Descending from Fantastic, John Brunner’s well-turned gimmick story The Last Lonely Man from New Worlds (the only story also to have appeared in the Wollheim/Carr best of the year volume), Norman Kagan’s audaciously zany The Mathenauts from If, and Kit Reed’s sprightly self-help/morality tale Automatic Tiger from F&SF.

Barely making the cut is Mack Reynolds’s Pacifist, also from F&SF, a sharp piece of political didacticism about a pacifist underground that uses decidedly non-pacifist means to fight against warmongering politicians, unfortunately too contrived to have much impact. Surprisingly, Arthur Porges, perpetrator of the dreadful Ensign Ruyter stories in Amazing, rises briefly from the muck with the affecting Problem Child, from Analog, about a professor of mathematics whose wife died bearing a mentally retarded child; the child proves to be anything but retarded in one significant way. This one gets “better than expected” credit. So does Training Talk, by the militantly eccentric David R. Bunch (Fantastic), in which he outdoes himself in grotesque lyricism (“It was one of those days when cheer came out of a rubbery sky in great splotches and globs of half-snow and eased down the windowpanes like breakups of little glaciers.”), complementing his even more grotesque plot. Edging into this category is The Search, a poem by (Merril says) high school student Bruce Simonds, from F&SF, which is minor but clever, pointed, and readable.

All right, downhill to the next layer, the less distinguished selections from the SF magazines, ranging from the merely competent or inconsequential to the actively dreary. There are several supposedly humorous trifles. Fritz Leiber’s Be of Good Cheer, from Galaxy, is an epistolary satire, a letter from a robot at the Bureau of Public Morale to a Senior Citizen (as they are known these days) reassuring her unconvincingly that the absence of humans and prevalence of robots that she observes is nothing to worry about. Larry Eisenberg’s The Pirokin Effect, from Amazing, is a more slapsticky satire about extraterrestrial signals received in a restaurant kitchen which may or may not be from the Lost Tribes of Israel, now resident on Mars; this one is distinguished from the Leiber story by actually being mildly amusing. The same is true of Family Portrait by new author Morgan Kent, from Fantastic, a vignette about the mundane domestic life of a family that proves to have unusual talents.

The same is unfortunately not true of The New Encyclopaedist, from F&SF, by Stephen Becker, a novelist (see last year’s A Covenant with Death) and translator of some repute, with no prior SF credits. This comprises several satirical encyclopedia entries about events in the near future, but their main purpose seems to be to prove the author’s superior sensibilities, and they’re more tedious than funny. I’m guessing the New Yorker rejected them. Czech author Josef Nesvadba’s The Last Secret Weapon of the Third Reich belongs here as much as anywhere—it’s from his collection Vampires Ltd., which is apparently devoted to SF stories. It’s a frenetic black comedy about a last-ditch Nazi effort to generate a new fighting force with a process for developing embryos to adulthood within seven days of conception; the story is less effective than it should be since . . . gosh . . . Nazis are kind of hard to satirize.

There are also a couple of yokel epics here, which is almost always bad news. Sonny, by Rick Raphael, from Analog (where else?) is a dreary attempt at humor about a kid from West Virginia whose psionic talents come to light after he is drafted into the Army. The Man Who Found Proteus, by the always promising but never quite delivering Robert H. Rohrer, Jr., from Fantastic, features a caricatured semi-literate miner encountering a hungry shape-changing monster and coming off no better than you’d expect.

Several other more conventional SF stories are just not very lively. Richard Wilson’s The Carson Effect, from Worlds of Tomorrow, like much of his work to my taste, is a rather limp account of strange human behavior in what everybody thinks are the last days, but prove not to be, a denouement explained by a gimmick reminiscent of Hawthorne’s Rappaccini’s Daughter. The Carson of the title is Rachel. Jack Sharkey’s The Twerlik, from Worlds of Tomorrow, is an alien contact story in which the alien, a planet-encompassing plant, tries to make sense of explorers from Earth landing in a spaceship; it’s an earnest effort (unusually for this author) that doesn’t quite revive a hackneyed theme. A Miracle Too Many, by Philip H. Smith and Alan E. Nourse, from F&SF, concerns a doctor who wishes he could save all his patients, and suddenly he can, with grim consequences that are all too obvious. Its problem is not ennui but predictability.

That’s an awful lot of lackluster for a book with “Best” in the title. More on that problem later.

Neighboring Provinces

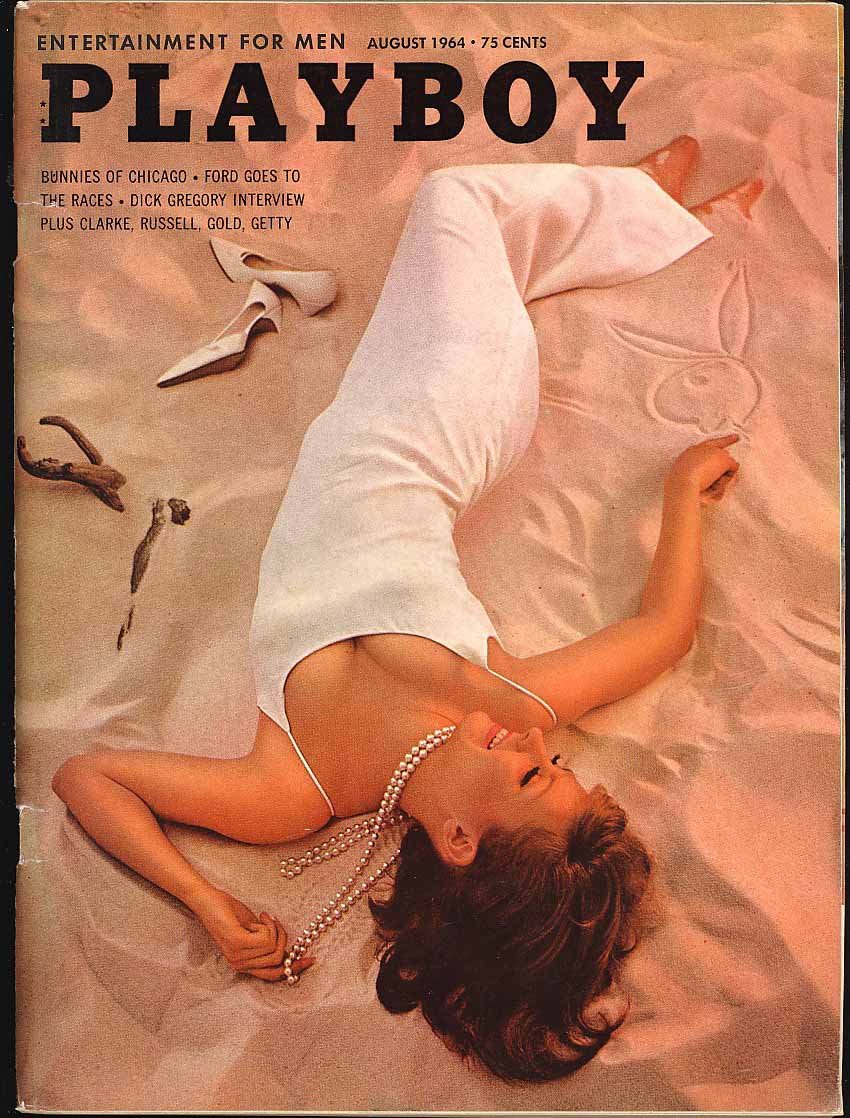

The next stratum consists of fairly straightforward SF/F that Merril has trawled or excavated from the established mainstream magazines in the way of SF/F. A couple of these are by well-established (or –remembered) genre names. One of the best in the book is Arthur C. Clarke’s The Shining Ones, from Playboy, about an encounter with the fauna of the sea, rendered with the same dignified enthusiasm as Clarke’s portrayals of human encounters with the Moon and the other planets. This is a writer who will never lose his sense of wonder, or his discipline in writing about it. Interestingly, the plot takes off from the notion of powering a city with energy derived from temperature differentials between oceanic depths and the surface. Maybe somebody should try that sometime. The other big name is John D. MacDonald, who wrote a lot of quite good SF from 1948 to 1953 but gave it up for crime fiction. Unfortunately his The Legend of Joe Lee from Cosmopolitan is unimpressive, a lame sort of ghost story about a teen-age hot-rodder whom the cops can’t catch, for reasons revealed at the end.

The others in this category are all satirical extrapolations of things the authors have seen around them, a standard maneuver in standard SF and a game that anyone can play—though not always well. The best of the lot is A Living Doll by Robert Wallace, from Harper’s; Wallace is said to be a photographer for Life, and the story to have been inspired by an encounter in a toy store with a doll that spoke to him and nibbled his finger. The narrator’s sullen and sadistic daughter wants a doll for Christmas, along with some needles and pins and a book on Voodoo. He discovers that dolls have become more sophisticated than he realized, and purchases one who proves to mix a mean Martini and to discourse knowledgeably about Mexican art—a considerable improvement over his daughter. The rest follows logically. Almost as good is Frank Roberts’s It Could Be You, from the Australian Coast to Coast (which seem to be an annual anthology of stories from the previous year, just like this one). In the future, it posits, the populace will be kept entertained by a televised game: one person in the city is selected to be killed, with a hundred thousand-pound prize to the winner; and clues narrowing down the victim’s identity are given through the day to build suspense (a man; never wears a hat; black hair; blue eyes; etc.). This is not exactly a new idea to readers of the SF magazines, but it’s sharply written and no longer than it needs to be. James D. Houston’s Gas Mask, from Nugget, one of many cheap Playboy imitations, is a reasonably well done “if this goes on” piece about future traffic problems and people’s adaptation to them.

And there are selections from places you wouldn’t think to look, but Merril always casts a wide net. The satirical motif continues, unfortunately in combinations of facile, arch and ponderous. Russell Baker’s A Sinister Metamorphosis is apparently one of his regular columns from The New York Times, taking off from the theme that sociologists “thought the machines would gradually become more like people. Nobody expected people to become more like machines.” James T. Farrell’s A Benefactor of Humanity—the one from the Socialist Call—is about a man who can’t read but loves books; however, he dislikes authors, and devises a machine to replace them. It’s overlong and not funny. Hap Cawood’s one-page Synchromocracy, from motive, is a rather undeveloped sketch of government by computer and constant public opinion polling.

Farther Out

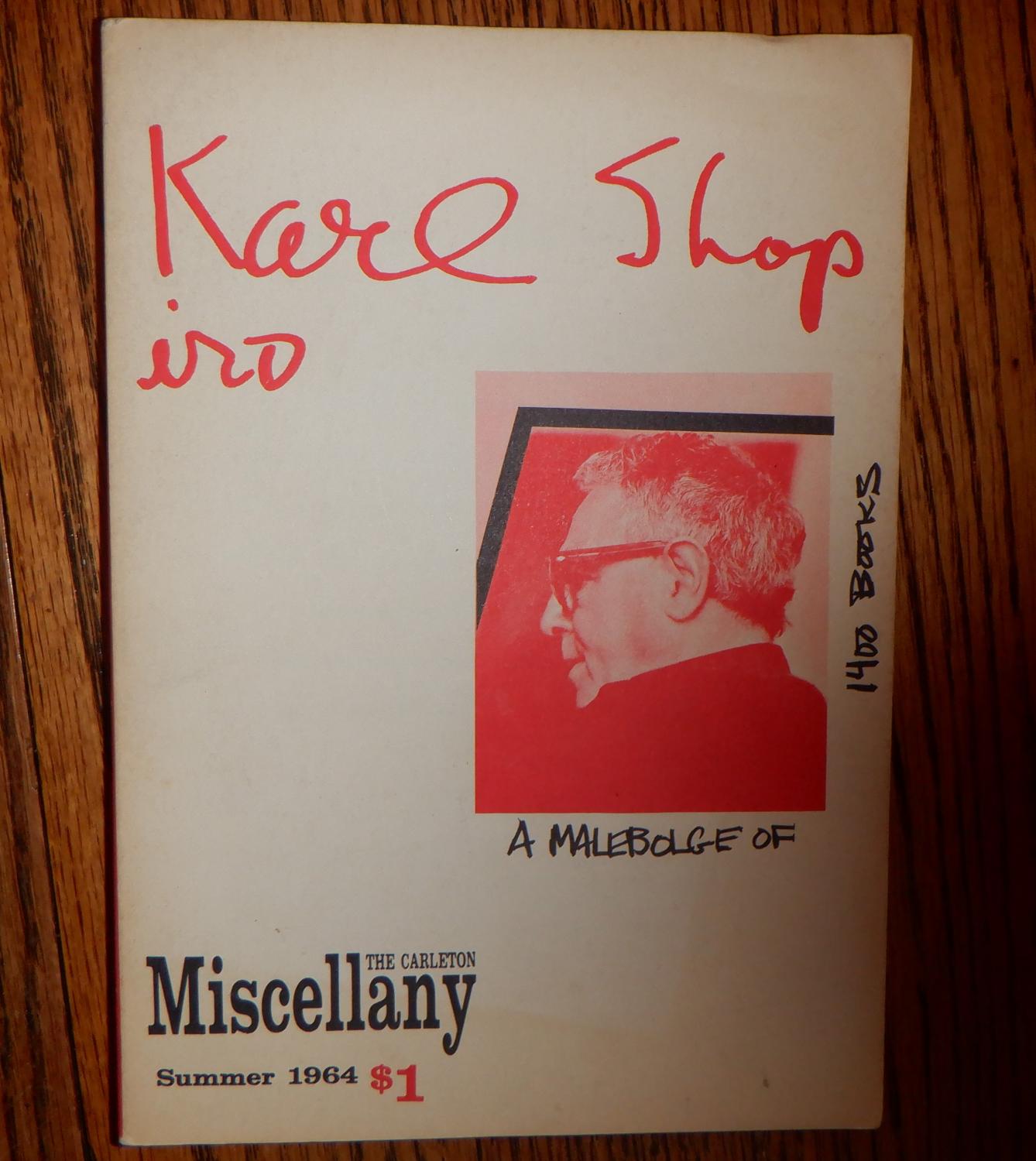

From here, things just get weird, for better or worse. Donald Hall, a well-known poet and former poetry editor of the Paris Review, is present with The Wonderful Dog Suit, from the Carleton Miscellany (literary magazine of Carleton College), about a precocious child who is given a dog suit, and takes to it; the dog becomes rather shaggy by the end. I suppose this is brilliance taking a day off. The Red Egg, by Jose Maria Gironella, apparently a well-established Spanish writer, is a jolly tale about a cancer which flees its home on the skin of a laboratory mouse and takes to the air, feeding on industrial smoke and other toxic delicacies, terrorizing the populace while contemplating which human victim to descend upon. It’s quite entertaining, but the point is elusive; too profound for me, I guess. This first appeared in a collection titled Journeys to the Improbable, collecting the author’s “psychic experience” over a period of two years.

Probably the weirdest item here—since I can detect no element of anything resembling S or F even by Merril’s ecumenical standard—is Romain Gary’s Decadence, from Saga (the men’s magazine? Really?) by way of Gary’s collection Hissing Tales. A group of mobsters goes to Italy to meet their charismatic leader, who after taking over a union was prosecuted and deported; now he’s eligible to return, but they find he has meanwhile become an acclaimed modernist sculptor with a rather different outlook than they had expected. M.E. White’s The Power of Positive Thinking, from New Directions, is a first-person story told by a smart, fanatically religious schoolgirl which amounts to a horror story with no trace of fantasy, the horror only suggested, but heightened by the relentless mundanity of the account.

The book closes with Yachid and Yechida by Isaac Bashevis Singer, from his collection Short Friday. Singer is among other things the book reviewer for the Jewish Daily Forward, and the story was translated from Yiddish. It is a theological fantasy about dead souls condemned to Sheol, a/k/a Earth, and their posthumous lives there, and it is absolutely captivating, one of the best things in the book. This Singer really has something going; if he works at it, he might crack F&SF.

Summing Up

So, what to make of this “best SF” anthology, in which much of the SF/F is just not very interesting and is outshone by some of the loose marbles Merril has found in other yards? At least part of the problem is her seeming unwillingness to include longer stories, which of course would displace multiple shorter ones and yield a less crowded contents page. But much of the best SF writing these days is at novella length or close to it; consider Jack Vance’s The Kragen and Roger Zelazny’s The Graveyard Heart, from Fantastic, and Gordon R. Dickson’s Soldier, Ask Not and Wyman Guin’s A Man of the Renaissance, from Galaxy. Merril would probably be better advised to devote a little more space to substance and less to short trifles.

But still, there’s a lot here—much of it quite good, much of it unexpected, and some of it both. This anthology series is still in a class by itself.

by Gideon Marcus

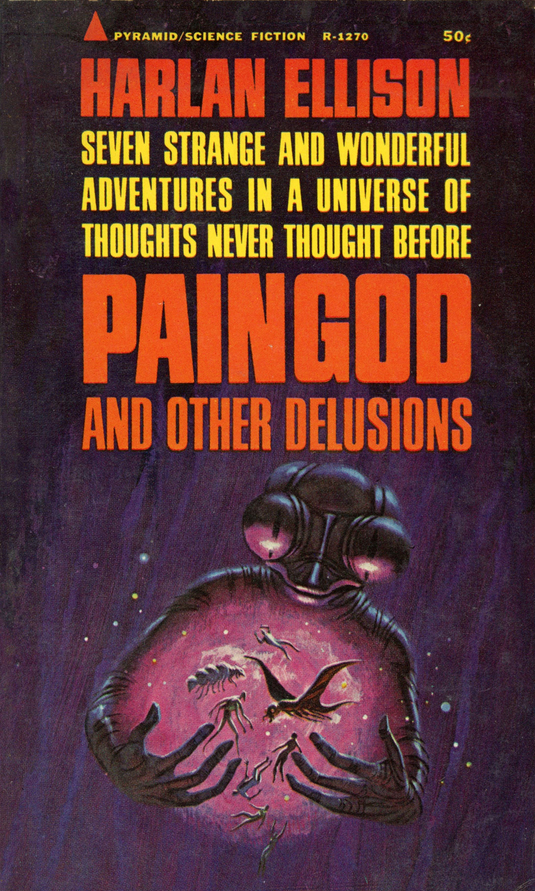

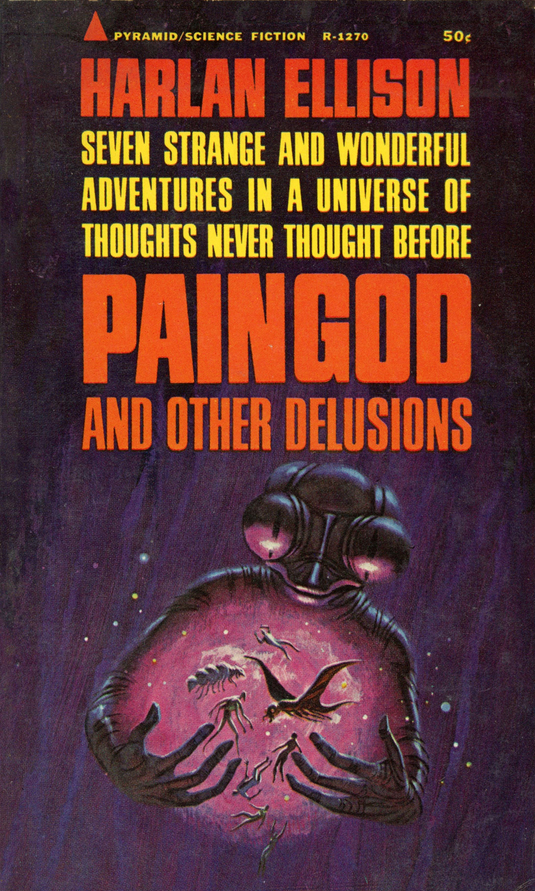

Paingod and Other Delusions

Three years ago, Harlan Ellison released his first collection of science fiction stories. It was a fine collection, representing the era of his writing career before he struck out for Hollywood to become a big-time screenwriter (some of his work not surviving to the small screen unscathed…)

Now he's back with a new collection. A mix of stories recently written and others excavated from the vault, it offers up a strange combination of mature and callow Ellison, though none of it is unworthy. Dig it:

by Jack Gaughan

Introduction

After seven stabs at it, Harlan reportedly threw up his hands and decided he wasn't going to write an introduction. Instead, we get a several page nontroduction that is probably worth the price of the book in and of itself. I read it aloud to my family while we were waiting to get into a new sushi place in town. It's excellent, funny, self deprecatory, and illuminating.

Paingod

If God is Love, why does He allow pain to exist? This moving, brilliant story tries to answer this question. Nominated for the Galactic Star last year and covered previously by Victoria Silverwolf, there's a reason it leads this book.

Five stars.

"Repent, Harlequin!" said the Ticktockman

In an increasingly time-ordered world, the wildest rebel is he who would gum up the works of society.

I didn't much care for this story when I first reviewed it, finding it a bit overwrought and consciously artistic. Ellison's introduction, in which he explains his congenital inability to mark time accurately, makes the piece much more understandable. I'd had trouble relating in part because my time sense is preternaturally perfect (I can tell you what time it is even after being asleep for hours). So, with the story now in context, I can understand the enthusiasm with which it's been received.

Four stars.

The Crackpots

An exploration of a planet of misfits, who it turns out are the real movers and shakers of the galactic federation.

Based on the odd characters Ellison observed when manning an adult book stand on 42nd Street, this is an older piece, and it shows. About ten pages too long and a little obtuse, but even young, imperfect Ellison is usually worth reading.

Three stars.

Bright Eyes

The former masters of the Earth have been diminished by war to just one representative and his oversized rodent sidekick. Like a salmon swimming upstream, he returns to the blasted surface to witness the destruction one last time.

Inspired by a piece of art (that later accompanied the story—you can see it at Victoria's original review—it's a vivid piece.

Four stars.

The Discarded

A plague turns a number of humans into "monsters", who are exiled to an orbiting colony. When a new outbreak occurs, suddenly the discarded find themselves valued as the potential source of a cure. But will normal humans ever really tolerate the deviant?

I will go out on a limb here — this is my favorite story of the collection, one I enjoyed when I first read it in the 1959 issue of Fantastic. It's a much more effective "misfit" piece than the previous story.

Five stars.

Wanted in Surgery

Automated surgeons displace their human counterparts. Are they truly infallible? And is it ethical to find fault in them?

This piece doesn't work on a lot of levels, plausibility-wise and narratively, as even Ellison concedes. I suppose it's here to fill space and to make sure it got in some collection.

Two stars.

Deeper than the Darkness

Another misfit, this time about a pyrokinetic recruited to destroy the star of an enemy race. Fools be they who expect a hated rebel to suddenly be overcome with patriotism…

This is another flawed, early piece that shows Ellison's potential without realizing it.

Three stars.

Summing Up

Two fives, two fours, two threes, and a two, not to mention a great Intro. If that's not worth four bits, I'm not sure what is. Get it!

![[November 8, 1969] Arabesques (December 1969 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/COVERARTSMALL.jpg)

![[December 24, 1965] Gallimaufry <i>du Saison</i>(<i>The Year's best Science Fiction</i> and <i>Paingod and Other Delusions</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651224covers-672x372.jpg)

![[August 21, 1964] The Good News (September 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640821cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 17, 1964] It's all Downhill(April 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640317cover-667x372.jpg)