[Have you gotten your copy of Rediscovery: Science Fiction by Women (1958-1963)? It's got some of the best science fiction of the Silver Age, many of the stories first appearing in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction!)

by Gideon Marcus

The Good Fight

1964 has been a year of struggle. The struggle to integrate our nation, the struggle against disorder in the cities, titanic power struggles in the U.S., the U.K. and now the U.S.S.R. The struggle to hold on to South Vietnam, to preserve Congo as a whole nation. The struggle of folk, rock, Motown, country, and surf against the inexorable British invasion.

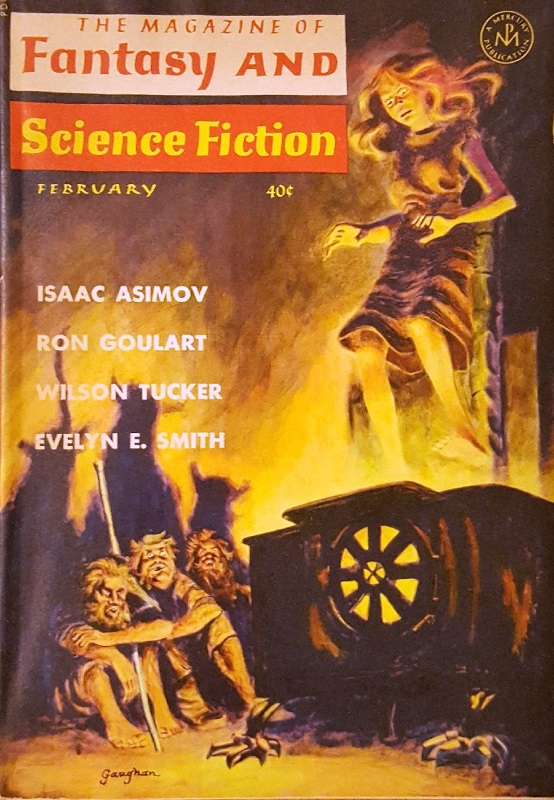

So it's no wonder that this month's Fantasy and Science Fiction makes struggle the central component of so many of its stories. This magazine is wont to have "All Star Issues" — this one is an "All Theme Issue":

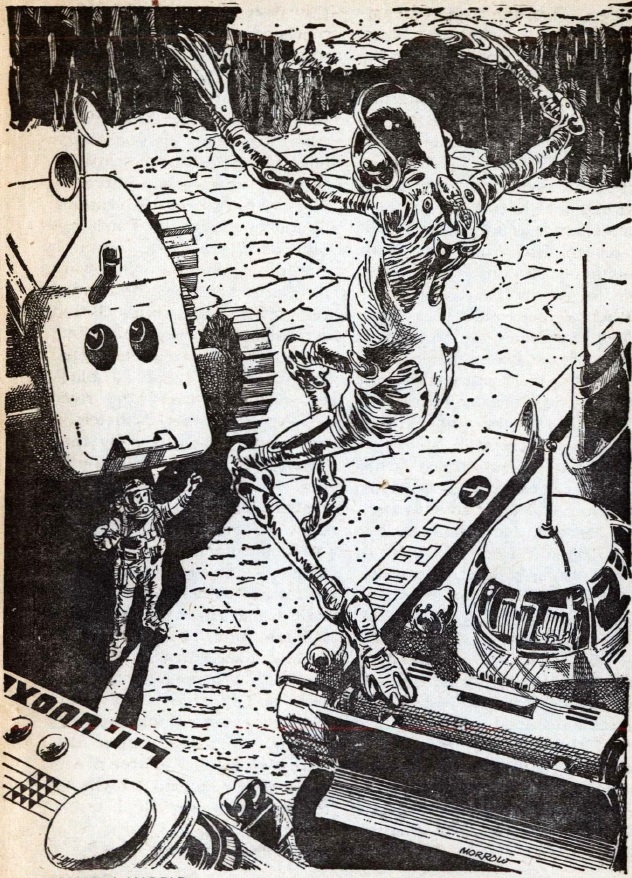

by Ed Emshwiller

The Issues at Hand

Greenplace, by Tom Purdom

Purdom, who just wrote the excellent I want the Stars (review coming in the next Galactoscope), depicts a 21st Century in which immortality has created a stranglehold on politics. Canny machine bosses can hold on to power indefinitely. Nicholson is a man who would break this power, loading himself up on psychically enhancing drugs and personally investigating "Greenplace", a stronghold neighborhood of the 8th Congressional District. There, he encounters resistance, violence, and a secret…

Remarkable for its melange of interesting ideas and surreal execution, it's a little too consciously weird for true effectiveness. Three stars.

After Everything, What? by Dick Moore

Two thousand years ago, genetic supermen ruled the galaxy. They weren't dictators; rather, they were created by humans to be the best that humanity could be (that's what the story says — I'm not endorsing eugenics). After a century of dominance, they all died out.

It's a well-written piece, but the conclusion is obvious from the beginning: the ubermenschen struggled against boredom…and lost.

Three stars.

Treat, by Walter H. Kerr

It used to be that, on Halloween, people would wear scary masks so that when they encountered bonafide spooks on their day of free reign, they would be mistaken for compatriots. Nowadays, the shoe is on the other foot — spooks can only freely walk the Earth on Oct. 31 since everyone mistakes their frightening faces for masks.

Cute? Three stars.

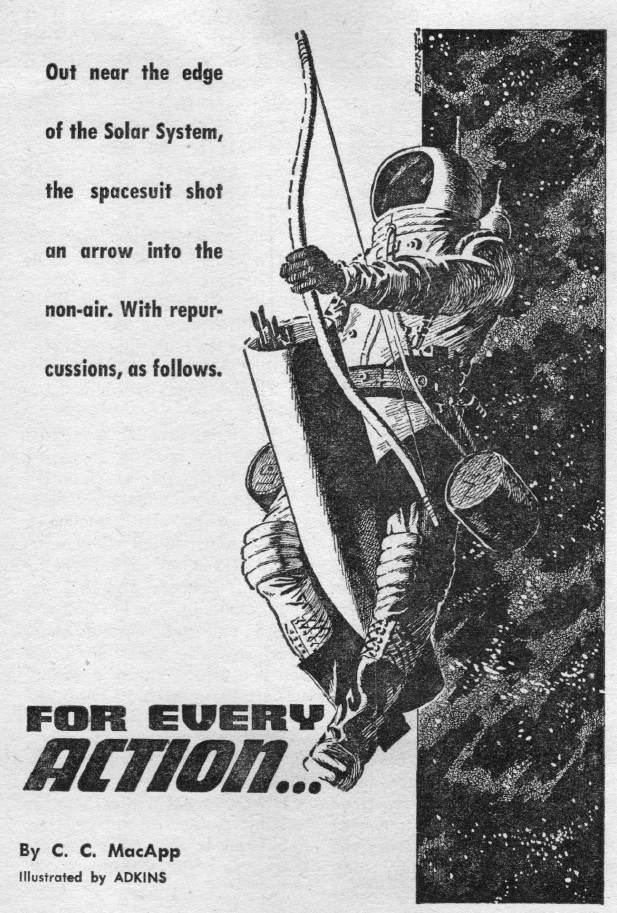

Breakthrough, by Jack Sharkey

Here, the struggle is Man vs. Machine. A chess-playing computer betrays its sentience by developing a sense of humor. So its creator, tormented with feelings of inferiority, shoots the machine dead.

Sharkey can be good. More often he can be bad. Here, Sharkey is about as bad as he ever gets.

One star.

Dark Conception, by Louis J. A. Adams

When the Savior comes again, will it be in the form of another virgin birth? And what happens when the new Mary happens to be Black?

This is the first piece of the issue that has some of the old F&SF power, but the ending doesn't pack a lot of punch since the conclusion is telegraphed, and the author doesn't do much with it.

Three stars for this missed opportunity of a tale.

One Man's Dream, by Sydney Van Scyoc

Against age, all mortals struggle in vain. A Mr. Rybik has himself "tanked" in life-sustaining fluids in the hopes of purchasing a few more years. But not for himself — he wants to preserve the other personality who lives in his head, the pulp adventurer called Anderson. This Anderson is more real to him than even his wife or his kids, entertaining, sustaining, allowing Rybik to enjoy a life of vicarious excitement.

But when Rybik's money runs out, he finds that no one in the real world wants to pony up dough to save a crazy dreamer who neglected his family. Can Anderson save him now?

Well crafted, it engages while it lasts, and then sort of fades away. Like Anderson.

Three stars.

The New Encyclopaedist – III, by Stephen Becker

Another of these faux articles written for an encyclopaedia, copyright 2100 A.D. This one details a latter day crusade against immorality by a McCarthy parody. Mostly a bore, though there is one genuinely funny line.

Two stars.

Where Do You Live, Queen Esther? by Avram Davidson

Esther is a Creole house-servant. Her struggle is with her employer, Eleanor Raidy, who treats her poorly. In typically overwritten fashion, the author details Esther's revenge. Only Avram can make seven pages feel like 20.

I understand Davidson is quitting the editorship of F&SF to devote more time to his writing. If this is the kind of stuff we can look forward to, he might consider an altogether different career. And it's a reprint, no less!

Two stars.

The Black of Night, by Isaac Asimov

Dr. A's article for the month details the struggle to answer Olbers' paradox: if the universe be infinite, and stars evenly distributed, why isn't the night sky as bright as the day's?

As one might guess, the issue is with the postulates. Neither are correct, as we now know. Asimov does his usual fine job explaining things for the layman.

Four stars.

On the House, by R. C. FitzPatrick

In the earlier story, Dark Conception, the husband of the pregnant Mary confronts Mary's doctor. Both husband and doctor are Black, but the husband considers the doctor a "Tom" and won't be satisfied with mere equality:

"I don' want what you want, man. I want what they got and for them to be like me now. I want to lead me a lynch mob and hang someone who looks at one of our girls. I want to rend me some of my land to one of them and let them get one payment behind. I want them to try to send they kids to our school. I want 'em to give me back myself like I was before, when I didn't hurt so bad that I better off dead."

Fitzpatrick's On the House is a deal with the Devil story, but the protagonist is a Black woman, and all she wants is to change places with "one of them".

It's another piece that would do a lot better with development beyond the punchline, but I at least appreciate the variation on the theme.

Three stars.

Portrait of the Artist, by Harry Harrison

If there is going to be one struggle that defines the modern age, it's the struggle to reconcile automation with personal dignity. Harrison, in this piece, shows the mental devastation that happens when even such an imagination-laden field as comic artistry can be done by a machine.

It was pretty good up to the end where (if you'll pardon the unintentional pun, given how the story ends), Harrison fails to stick the landing.

Three stars.

Hag, by Russell F. Letson, Jr.

Is a witch's pox effective against modern vaccination?

Another pleasant (if forgettable) prose poem.

Three stars.

Oversight, by Richard Olin

Wacky doctor wins his struggle against aging by infusing his cells with planaria (flatworm) DNA. It has unintended consequences.

Another story with an obvious ending — and this one doesn't make biological sense.

Olin's last (and first) story was better. Two stars.

The Third Coordinate, by Adam Smith

We end with the struggle to reach the stars. The concept is novel: humanity has invented a teleporter, but while direction can be controlled, distance cannot. What its operators need is three known destinations, coordinates that can be used to calibrate the device so that accurate ranging can be done.

Great idea. Very poor execution. Nothing happens for the first 20 pages but some of the clunkiest exposition and character development I've read in a while. And there's no tension in the end, either. Pilot succeeds, end of story.

Two stars, and a hope that the theme gets picked up by someone with more chops.

Summing Up

As it turns out, the biggest struggle this month was finishing the damned magazine. Conflict is vital to any story, but it's only one component. Execution and development matter, too. Even Davidson's story intros have lapsed into badness. I'm looking forward to the editor's departure from F&SF; any change has to be an improvement, right?

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[October 20, 1964] The Struggle (November 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641020cover-660x372.jpg)

![[September 8, 1964] It's War! (The October 1964 <i>Galaxy</i> and the 1964 Hugos)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640908cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 8, 1964] Rough Patch (June 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640508cover-672x372.jpg)

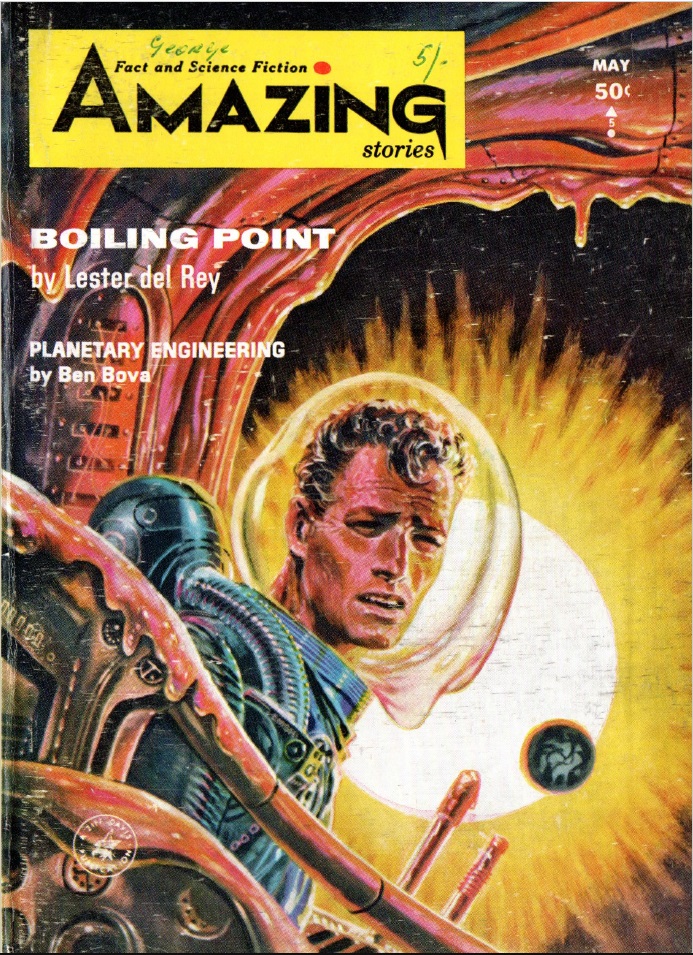

![[April 14, 1964] COOKING WITH ASH (the May 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640414cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 9, 1964] Deviant from the Norm (April 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640309cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 21, 1964] For the fans (March 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640219cover-665x372.jpg)

![[January 18, 1964] Pig's Lipstick (February 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640418cover-554x372.jpg)

![[October 12, 1963] WHIPLASH (the November 1963 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631012cover-672x372.jpg)