by Gideon Marcus

A slow burn

The British love writing about the end of the world.

Whether it's J.G. Ballard depicting a drowning world, Nevil Shute showing us clouds of atomic radiation slowly enveloping the globe, the cinema showing the day the Earth caught fire, or John Wyndham terrorizing a blind world with man-eating plants, the UK has been fertile ground for a particular kind of disaster story. While presenting global catastrophes is not unique to Britain, U.K. authors are more apt to focus on the social ramifications, and also the aftermath, rather than the more flashy destruction scenes. Moreover, British SF tends to take its time with disasters, letting you stop for a contemplative tea rather than maintaining a continuous mad dash. Of course, Americans write contemplative post-disaster too (viz. Pat Frank's Alas, Babylon, but it's rarer.

Brian Aldiss, the vanguard of the British "New Wave" of science fiction, had already made his mark in this genre with Hothouse, a portrayal of Earth's far-future where humans have reverted to knee-high savages and plants have displaced virtually all of the animal kingdom. A popular series and then a fix-up book, Hothouse was a hit, winning a Hugo a couple of years back.

Now, the prolific Oxonion (by residence, not degree) has produced the latest in inexorable aftermath fiction: Greybeard.

Winding down

The basic premise of Greybeard is like a cross between On the Beach and John Christopher's The Death of Grass (No Blade of Grass in the United States). In 1981, orbital atomic tests cause the Earth's protective Van Allen Belts to waver, and the Earth is scoured with extraterrestrial radiations. Most large mammals are adversely affected; they sicken and die, they cease to breed true. Humans are hit worst of all: half the world's children succumb to the ensuing illness, and virtually all humanity is rendered sterile.

Aldiss begins his story in 2029, after society has largely collapsed. The viewpoint character is Algernon Timberlane, generally known as "Greybeard" for his signature adornment. Of course, some fifty years after "the Accident", everyone is grey, but Algy stands out for being among the youngest of humanity's remnants, a spry 54-year-old in a world of old coots. An intellectual and possessed of vigor, and also married to one of the youngest and loveliest women yet living (Martha Broughton), Greybeard stands out, and he has many years left for adventure.

Adventure he does, in a sort of quiet, understated fashion. From the first chapter, the book wends in two chronological directions. Going forward, Algy and Martha leave their authoritarian community of Sparcot after it is overrun with feral stoats, their goal to reach the coast and see what's left of the world before it decays completely to a natural state. Going backward, we journey stepwise to the immediate aftermath of the Accident, first to the warlord era of 2018, then to the world wars of 2001 as nations struggled to secure the last viable children, and finally to Algy's youth, before humanity is certain of its doomed status.

A British manner of storytelling

Greybeard does an excellent job of exploring humanity with a hollowed out spot where its legacy should be. It's a fascinating study, a story of old people (men and women equally represented) in a field normally dominated by the young. At first, our species tries to carry on, business as usual. We then fall by stages into strife and then a senescent blurriness. In other words, as a race, we age and begin to die.

Aldiss is never in a hurry to tell his story, letting the reader soak in the sights and smells of the slowly decaying civilization. At the same time, neither does the pace lag, with Algy moving around quite a bit and meeting an interesting ragtag of other survivors. The book is in many ways a travelogue of southeast England, with Aldiss' home of Oxford featuring prominently. This intimate familiarity with the region adds verisimilitude to a very immediate-feeling tale.

The author also cuts the subtle horror of the situation with an arch sense of humor; for instance, the journalistic organization Algy joins after the wars, in order to document the last days of humanity, is called Documentation of Universal Contemporary History, for which Timberline is assigned to the English branch. Yes — DOUCH(E). The advancing senility of the people Greybeard meets is at once deeply chilling and comically ridiculous. In other words, the situation is hopeless but not serious.

Hope or despair at the bottom of the box?

Of course, the overriding question on everyone's mind (particularly the reader's) is whether or not there are any viable children left on the planet. There are hints given throughout; however, certain verification yea or nay is reserved for the very end. Either answer would work, but would result in wildly different tales and messages. I liked the path Aldiss chose.

In any event, Greybeard is definitely one of the stronger books of the year, and another excellent outing by Mr. Aldiss. Four stars.

photo by John Bulmer

[We have exciting news! Journey Press, the publishing company founded by the team behind Galactic Journey, has just launched its first book. We know you will enjoy Rediscovery: Science Fiction by Women (1958-1963), a curated set of fourteen excellent stories introduced by the rising stars of 2019.

If you enjoy Galactic Journey, you'll want to purchase a copy today — available physically and virtually!]

![[August 31, 1964] Grow old along with me (Brian Aldiss' <i>Greybeard</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640831cover-329x372.jpg)

![[August 29,1964] Coming to You Live via Satellite](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Mrs_ODonahue.jpg)

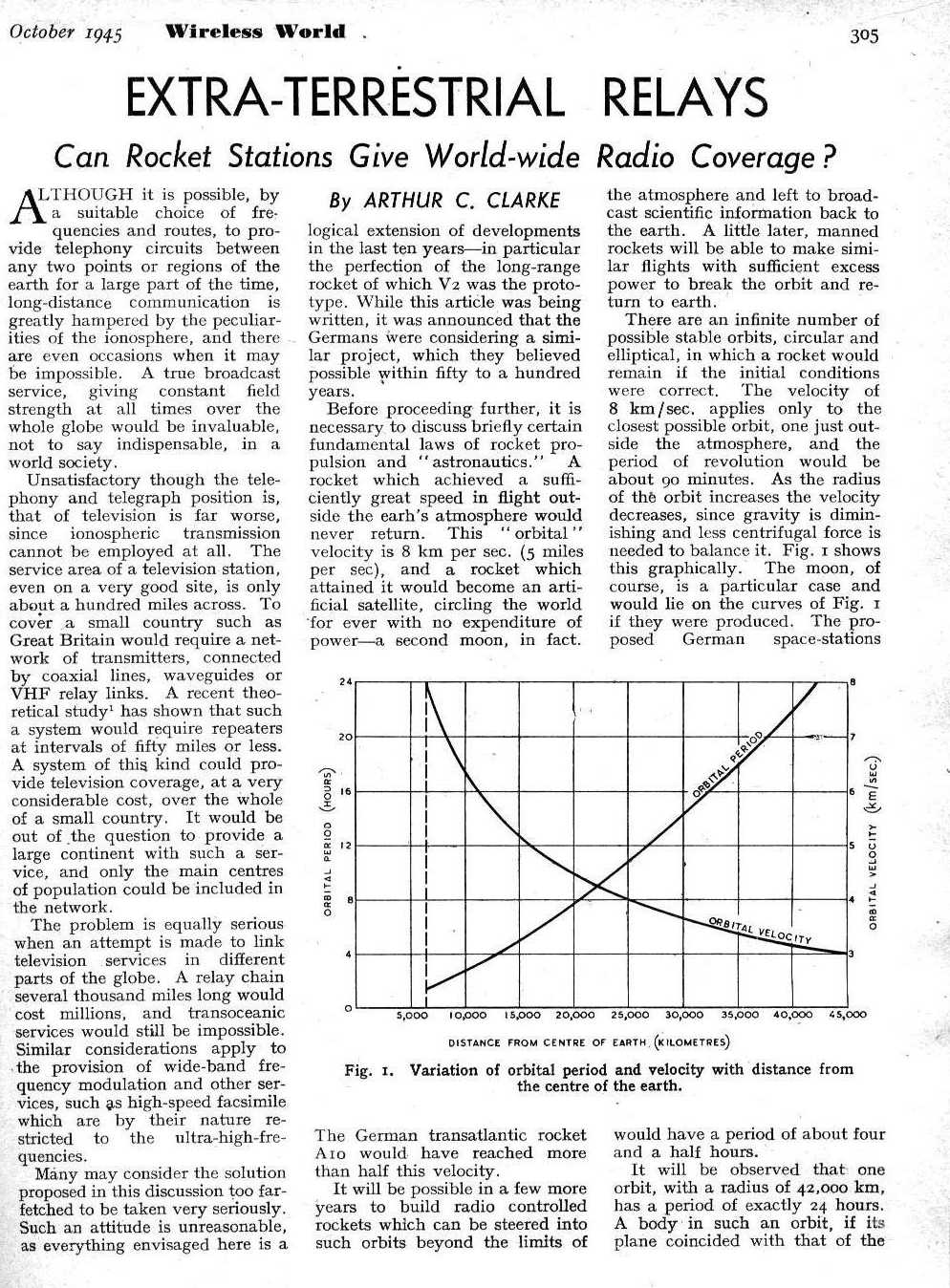

The first two pages of Mr. Clarke's seminal article on communications satellites. As a science fiction author, I guess he couldn't resist the title.

The first two pages of Mr. Clarke's seminal article on communications satellites. As a science fiction author, I guess he couldn't resist the title.

![[August 27, 1964] Change..? ( <i>New Worlds</i>, September-October 1964)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640827newworlds-1-553x372.jpg)

![[August 23rd, 1964] The Reign Of Boredom (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Reign Of Terror [Part 1])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640823allisforgiven-672x372.jpg)

![[August 21, 1964] The Good News (September 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640821cover-672x372.jpg)

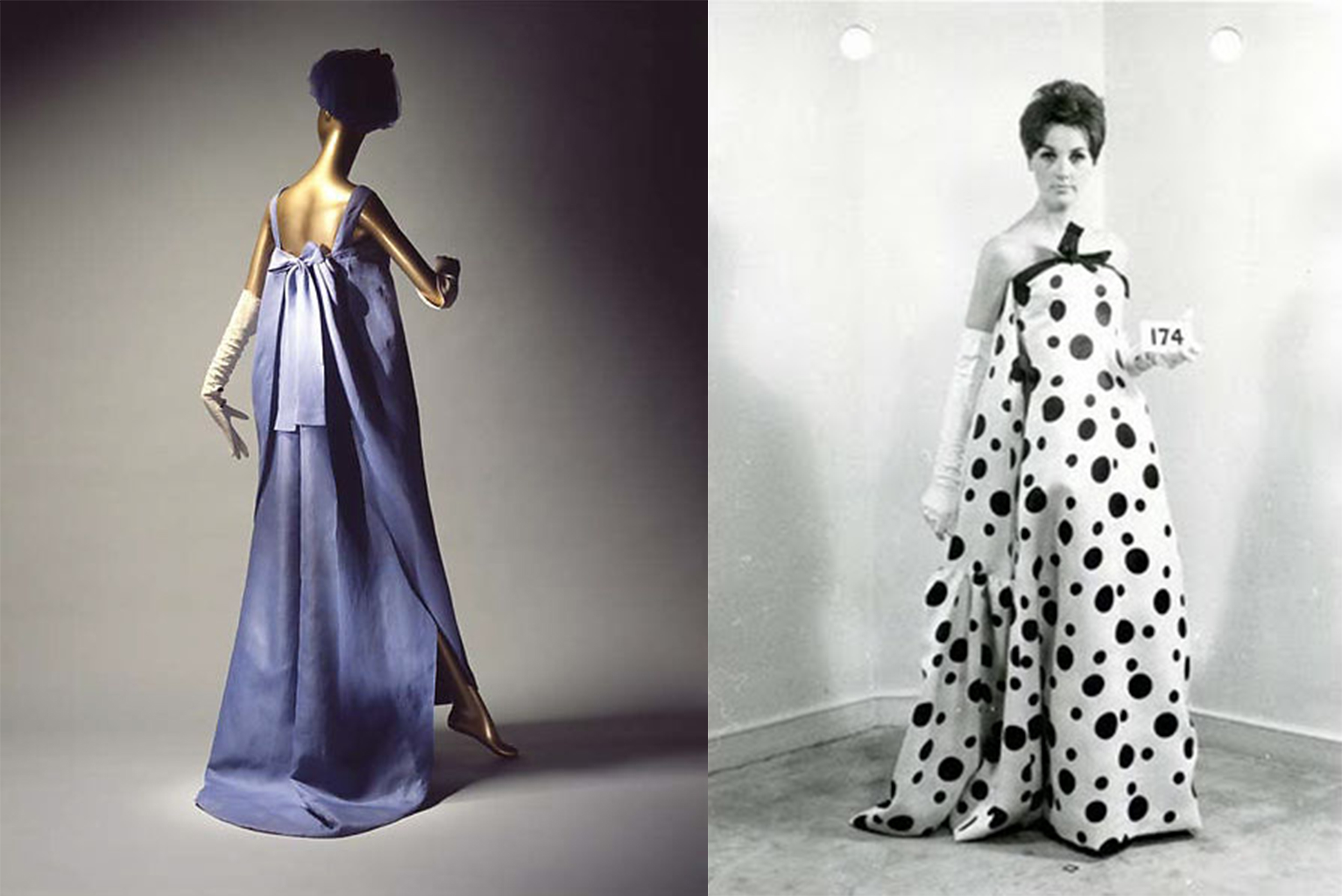

![[August 19, 1964] Seasonal Musings: Fall/Winter 1964](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640819a01-564x372.jpg)

![[August 13, 1964] Plus ça change (September 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/amz0964cover-2-649x372.png)

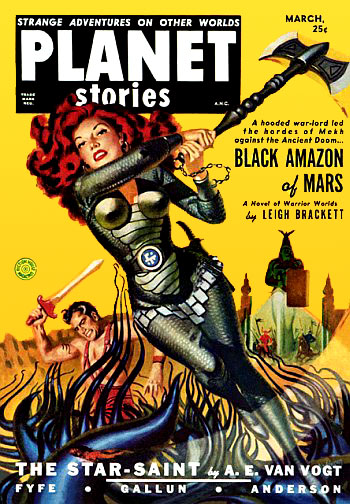

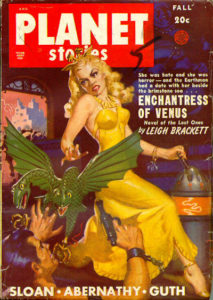

![[August 11, 1964] Leigh Brackett Times Two: The Secret of Sinharat and People of the Talisman (Ace Double M-101)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Planet_Stories_March_1951_cover-350x372.jpg)

Though upon closer examination

Though upon closer examination

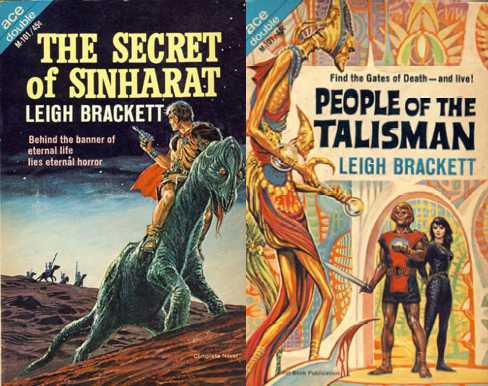

Of course, there are also differences. The Valley of Creation is set on Earth, in a hidden valley in the Himalaya, while The Secret of Sinharat is set on Mars. And Eric John Stark is a much more developed and interesting character than the rather bland Eric Nelson. Nonetheless, the parallels are striking. Edmond Hamilton and Leigh Brackett are not known to collaborate like C.L. Moore and her late husband Henry Kuttner did. But given the similarities of both stories and the fact that they were written around the same time, I wonder whether Brackett and Hamilton did not both write their own version of the same basic idea.

Of course, there are also differences. The Valley of Creation is set on Earth, in a hidden valley in the Himalaya, while The Secret of Sinharat is set on Mars. And Eric John Stark is a much more developed and interesting character than the rather bland Eric Nelson. Nonetheless, the parallels are striking. Edmond Hamilton and Leigh Brackett are not known to collaborate like C.L. Moore and her late husband Henry Kuttner did. But given the similarities of both stories and the fact that they were written around the same time, I wonder whether Brackett and Hamilton did not both write their own version of the same basic idea.

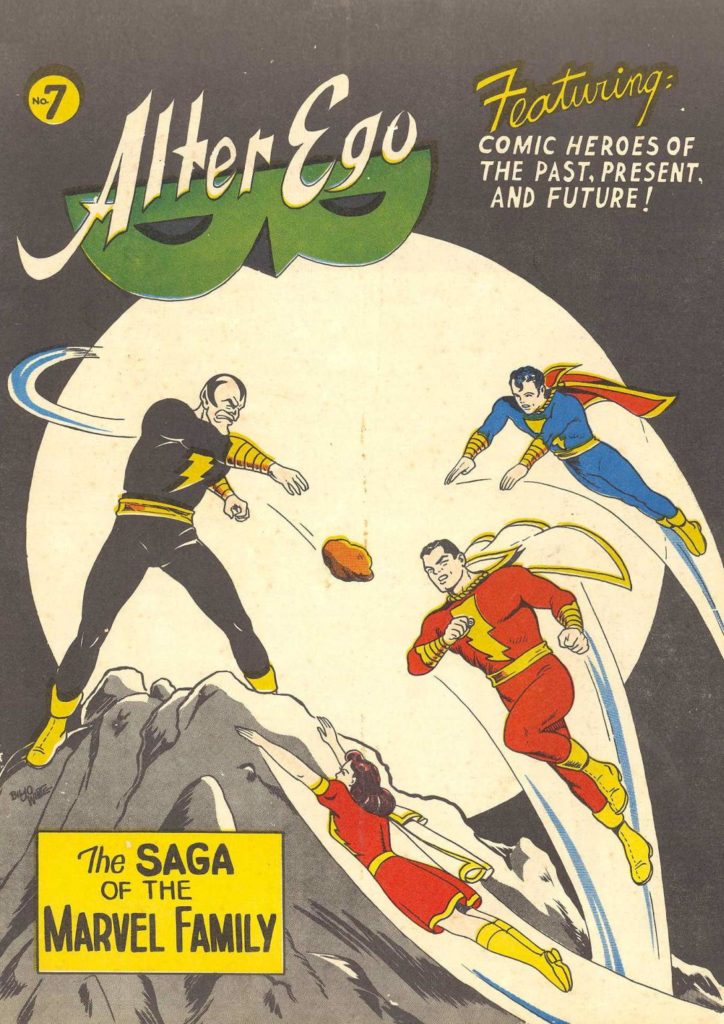

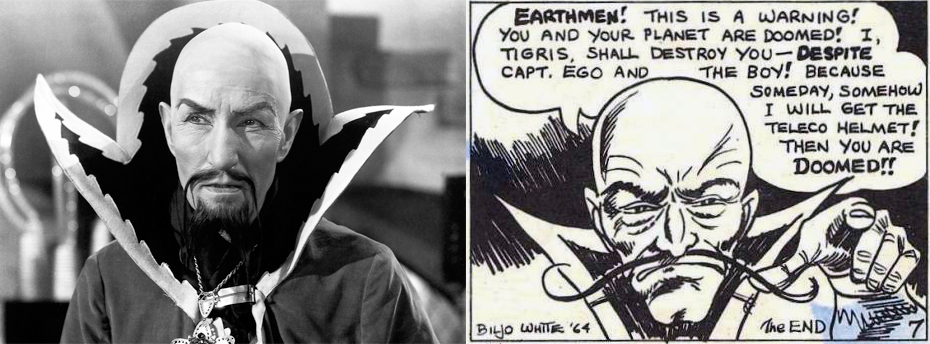

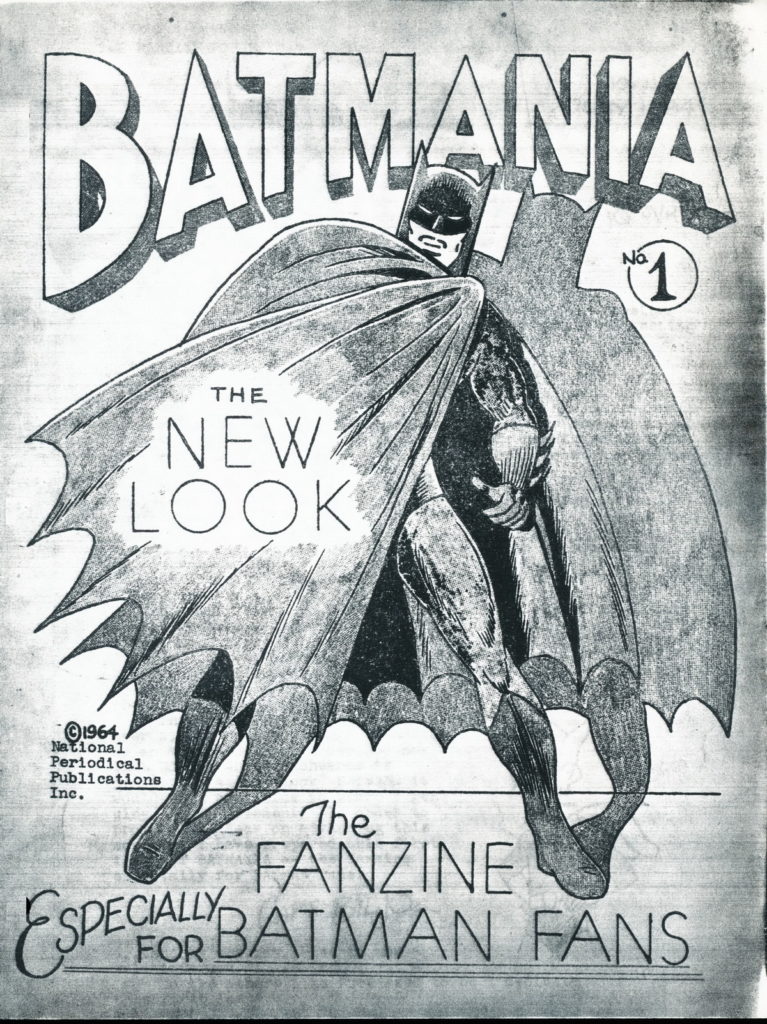

![[August 9, 1964] Heroic Considerations (Fall 1964 <em>Alter Ego</em>, July 1964 <em>Batmania</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640809AlterEgo7-cvr-672x372.jpg)