[The Journey meets extraordinary people in its travels, many of whom go one to join the endeavor. A fan we met at the most recently attended convention tore into the back issues and promptly fell in love with one of the featured stories. It led to an epiphany, which resulted in this lovely article you see below, on navigating the Symplegades of sex and gender in our modern year of 1964…]

by Napoleon Doom

There’s something undeniably rewarding about stumbling upon a piece of literature that resonates with you. “A Matter of Proportion” by Anne Walker, had lain in wait for me like a literary landmine, set in 1959. Though the piece is now five years old, considering the social milieu at present, this is worth revisiting, and not just because it’s an excellent read.

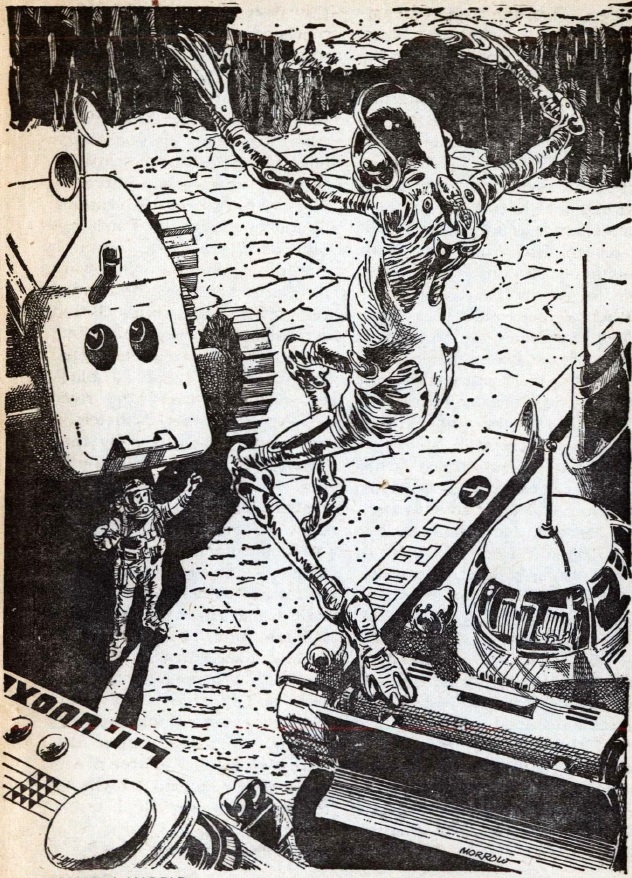

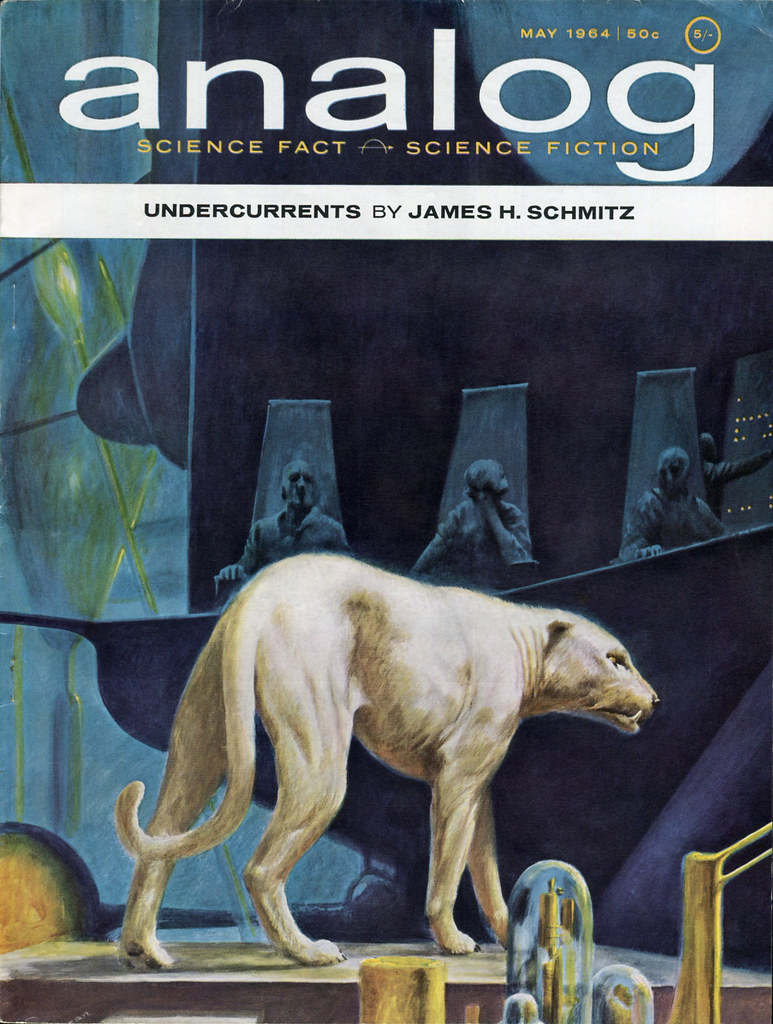

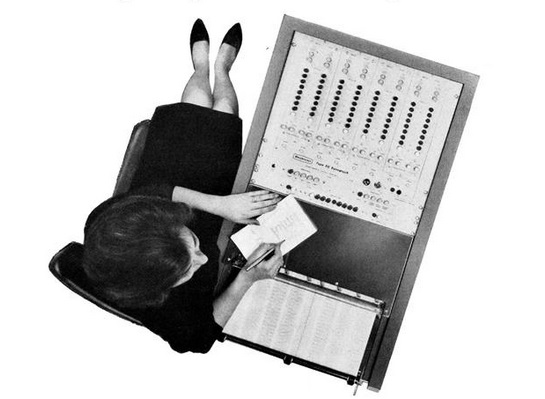

The story is narrated through Special Corps Squad Leader, Willie. Their squad is charged with laying mines to stop a nebulous enemy force, simply called Invader. Upon my first reading (and prompted by the art accompanying the story), I presumed Willie to be male.

However, on subsequent readings, I took notice of how careful the author was to never address Willie by specific pronouns. Aside from the singular use of the term “Daddy-o,” by second in command Clyde Esterbrook, the narrator is addressed in the neutral. This use of slang may be more indicative of Willie’s position as the head of the unit, or perhaps even Clyde’s own beatnik leanings than of Willie.

When the Special Ops team is planting mines along an elevated railway, Willie “felt the hum in the rails that every tank-town-reared kid knows.” There is a conscious effort to avoid claiming Willie as a tank-town boy or girl.

When Willie delves into the unusual past of second in command, Clyde Esterbrook, he responds, "You're the only person who's equipped for it. Maybe you'd get it, Willie." The use of the term “person” here, instead of man or woman, keeps Willie’s gender objective. The reader is allowed to embody this character, and ascribe the gender of their choosing.

I’ve struggled of late with being seen as an ill fit for my gender. How lovely a notion to not be held hostage by it! With Betty Freidan’s “The Feminine Mystique” flying off the shelves, women for the first time feel free to take an introspective look at themselves and what it is they truly want from life. While this is potentially a step forward, the truth is that at this moment in time, we have no point of reference for what a self-actualized “person” looks like, only a self-actualized man. Ergo, the natural inclination is to imitate the masculine, and forsake all things feminine in pursuit of self-fulfilment. There’s an irony in that.

We see this in the fashions coming out of Europe. Shift dresses, devoid of waistlines, disguise the curves indicative of womanhood. Femininity must be hidden. This isn’t equality; it is conceding that women are inferior and erasing them.

Yet I have a sickness, perhaps even a perversion. I confess, I have a love for all things feminine and glamorous. This is exacerbated by the fact that I am, myself, a woman.

Femininity, even in its most unadorned form, is viewed as a kind of manipulation. The mere feminine form forces some people to feel things against their will, licentious, disgraceful things. Perhaps because of this, women are encouraged to be understated and subdued — that is, if they want respect. A sound, intelligent woman must become the picture of neutrality for society to condone her. She exists not for herself, but to graciously reflect the wants of those around her — just as Willie does for the reader.

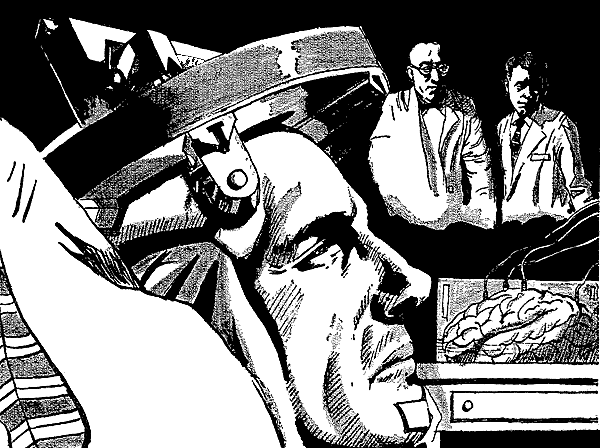

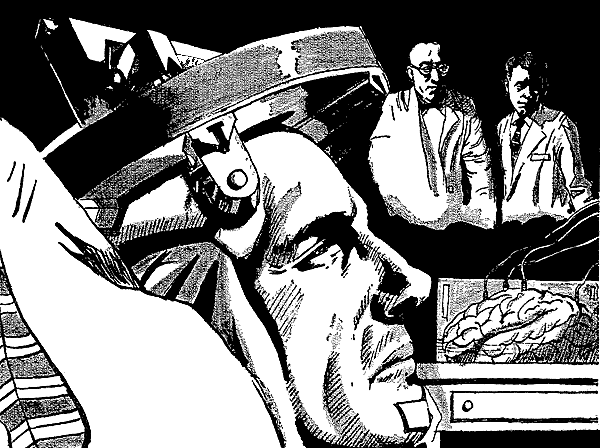

Willie clearly lives in a distant future. Co-ed military forces, lead by a person of unresolved gender aren’t the only suggestion of this. In Willie’s time, walkie-talkies have been abandoned in favour of “ICEG—inter-cortical encephalograph”. These are communication devices “planted in [an operative’s] temporal bone”, allowing all members of a team to enjoy a sort of mechanical telepathy.

This collective mind becomes the driving force behind this story, as the special ops team rides piggyback on ICEG mate, Clyde Esterbrook’s, senses. They watch through Clyde’s own eyes as he performs impossible feats of bravery, with an almost preternatural grace. This piques their curiosity. Who is Clyde, and how did he come by these uncanny skills?

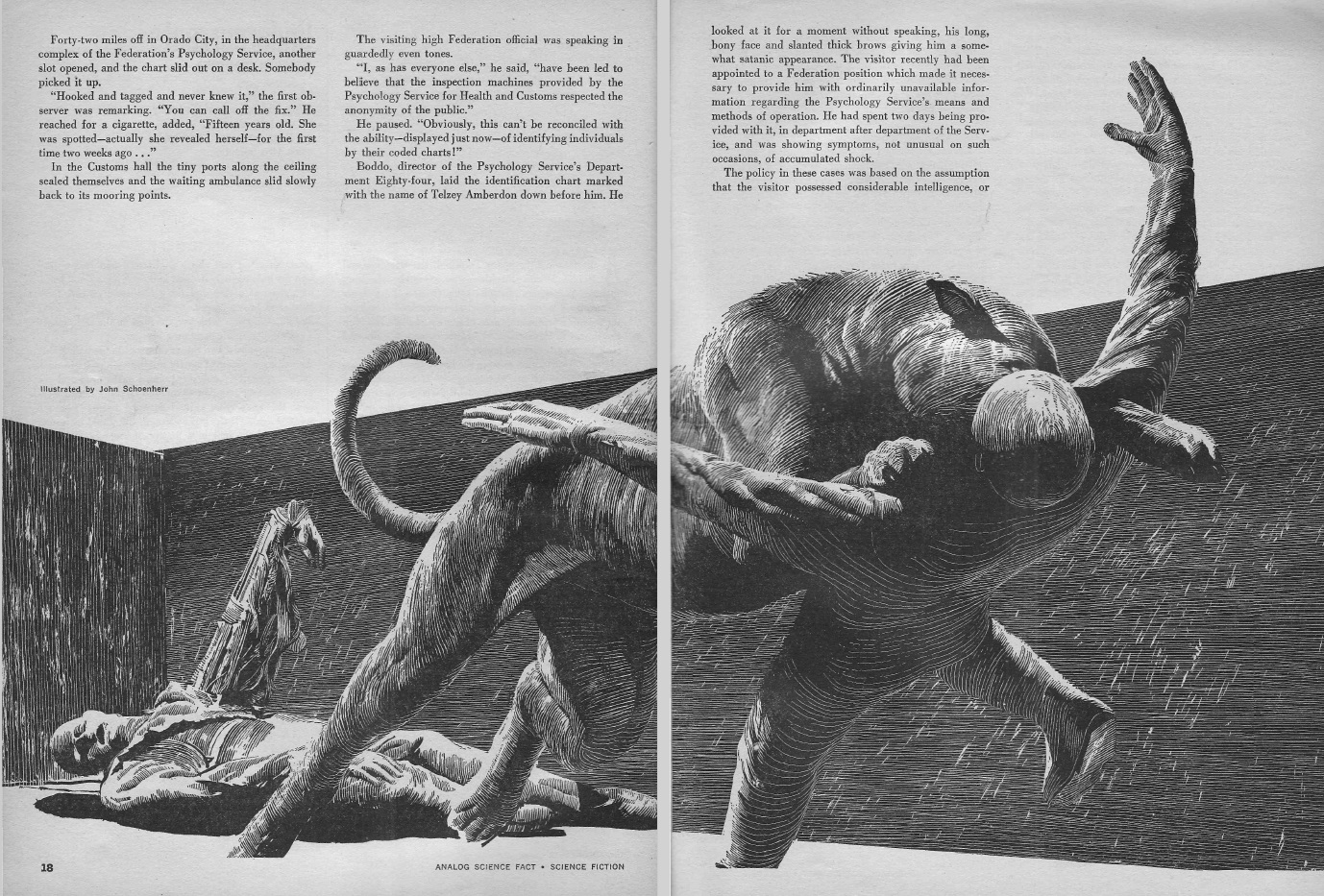

Clyde is perhaps as much an anomaly as Willie. He is described as a “big, bronze, Latin-Indian with incongruous hazel eyes.” I imagine a non-white person among the higher brass would be something quite shocking to many enlisted men. Clyde of course seems unbothered by what others may think of him. Rather than feeling violated by their compatriots digging through his skull, Clyde seems pleased by the opportunity to scatter his heroic chestnuts.

“There's always a way… if you're fighting for what you really want.”

Brave though he may be, Clyde proves far more reluctant to divulge memories from his past. When Clyde lays claim to having been a survivor of Operation Armada, Willie immediately knows something is amiss. That particular mission had only one survivor, Edwin Scott. He had been a medical student, rendered paraplegic by the ordeal. Scott had been a “snub-nosed redhead” and Clyde most definitely was not.

Bothered by his deception, Willie asks Clyde what he knows about Edwin Scott. Clyde’s answer is one that could never have been anticipated.

"Well, I was Edwin Scott, Will."

Clyde goes on to make the claim that the body he now inhabits was formerly that of “a man called Marco da Sanhao”, a former wrestler from Brazil. He had been rendered brain dead during a bombing, and thus became specimen for an experimental brain transplant procedure. Edwin Scott was willing to do whatever it took to be the recipient of this abandoned body and escape his wheelchair.

Scott, an educated white man, enjoying all the benefits granted to him by society – save the limitations of his disability- elected to live the rest of their life as a person of colour. Race, every bit as much as gender, is used to consign people to a certain station in life. Scott’s freedom however, is not one defined by race. The promise of having returned function of his body outweighed any fear of judgement.

While we can’t know the political climate of Willie and Clyde’s world, we live day to day in that of their creator. Willie and Clyde represent two methods of coping with the mercurial demands of society, which is what I imagine Invader is symbolic of. Invader has no real name, no affiliation, no identifiable features, not even a clearly understood motive. It is simply a force that attacks and compels those who would oppose it into submission.

In the battle against Invader, Willie fights camouflaged in shades of neutral, becoming invisible and pliant. For civilians, like you and me, our minds are an escape. We have a certain freedom that Willie no longer enjoys now that their mind is one with the ICEG collective.

Clyde, conversely, undergoes a metamorphosis into something more conspicuous, a “big, bronze, Latin-Indian with incongruous hazel eyes.” He is unafraid of the societal consequences if it means he has a chance for his own self-fulfilment. At the same time, he believes this fulfilment can only come from shedding his disabled body.

As a female author, I was especially struck by Walker’s execution of these two characters. I am well aware of the prevailing attitude towards women authors as being subpar. Women, they say, are consumed by sentimentality, and romantic caprices. Their work lacks substance or innovation, and is just a pale imitation of the craft. Like Clyde, I had come to see myself as being handicapped. It’s why I adopted a male nom de plum, hoping to have my work evaluated on its merits alone.

Like many writers, I insert myself into my stories. I enter the literary world not as an androgynous omnipresence like Willie, but as a man. In my dreams, graphic novels and audio-dramas, I fashioned myself a new body from words and pictures of my own creation. This body, the body of Napoléon Doom, doesn’t have to live shrouded and subdued in exchange for respect. Napoléon can be flamboyant and bold without apologies- in fact people adore him for it, he’s such an iconoclast!

It’s a fantasy of course. People celebrate effeminate men like those long-haired The Beatles, or the mod boys of Carnaby street, so long as they remain on stage or in magazines. In the mundane world, such men are far from adored. They are ridiculed, or worse, violently brutalized as punishment for their failure to conform. Perhaps they too force some people to feel things against their will, licentious, disgraceful things.

In much the same way, I imagine Edwin Scott fantasized about life inside Da Sanhao’s body. In wartime, Clyde was appreciated for his strength and cunning. People might have been willing to overlook the fact that he was a “big, bronze, Latin-Indian” so long as he served a function in Special Ops. However, Clyde has never existed in the mundane world.

Scott had experience with the injustices suffered by the handicapped. He chose to abandon his body because of them. As Clyde, he has yet to experience racial prejudice. We can hope that in this distant future, society has evolved to be more accepting. The problem with society of course, is that it’s made up of people, and people are notoriously intolerant of differences.

I’m well aware of the sideways glances I receive, and the whispers that go on behind my back. I’m a sad throwback to a bygone era when glamour and beauty were cherished rather than denounced as tools of oppression. Mocking people like me helps others distinguish themselves as sophisticated and modern by comparison. Yet, I’m satisfied with myself, or rather selves. The rest of the world seems split into factions, all equipped at birth with their own ICEGs. They are one mind, with many eyes, easily falling in step with the unwritten rules reverberating through their heads. I am not among them.

I think about my nieces and nephews, and the future they might live in. Regardless of gender, there will be some flaw, some difference that they will be shamed for. I have no expectations of this world becoming a more sensitive, caring place. I instead hope that they will learn to be confident, and satisfied in themselves, rather than living costumed in the expectations of others.

I wonder how Clyde will fare? He can never take his costume off.

[You can meet Napoleon Doom and see her amazing projects at her own abode…]

![[May 16, 1964] A Mirror to Progress (Chester Anderson and Michael Kurland's <i>Ten Years to Doomsday</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640516cover-595x372.jpg)

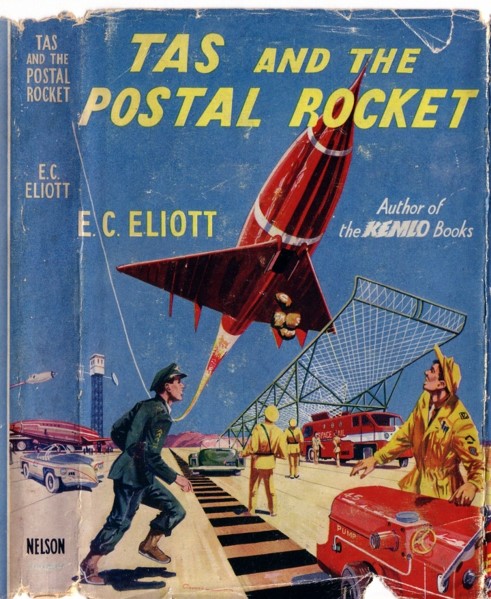

![[May 14, 1964] Special delivery! (getting your mail via rocket)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640514Taspostalrocket-491x372.jpg)

![[May 12, 1964] Secrets Beyond Human Understanding (<i>The Outer Limits</i>, Season One, Episodes 29-32)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640512a-672x372.jpg)

![[May 10, 1964] STUCK IN THE MIDDLE (the June 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640510cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 8, 1964] Rough Patch (June 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640508cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 6, 1964] The Predicament: <i>Transit</i> by Edmund Cooper](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640506transitamazon-375x372.jpg)

![[May 4, 1964] A Matter of Proportion, Revisited](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640504napdress2-672x372.jpg)

![[May 2, 1964] The Big Time (May 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640502cover-672x372.jpg)

![[April 30, 1964] Mary Mary Quite Contrary: Mary Quant and the Modern Woman](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640430a03-672x372.jpg)

![[April 28, 1964] Out With the Old…. (<i>New Worlds, May-June 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640428cover-555x372.jpg)