by Rosemary Benton

When I read that there was to be a film adaptation of Shirley Jackson's 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House I was over the moon. In this time of character driven thrillers blasting onto the silver screen thanks to Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles, I was excited yet apprehensive to have one of my favorite author's books translated into a film script. Upon learning that the talent of Robert Wise, director of The Day the Earth Stood Still and West Side Story, was going to be attached to the project I felt I could rest easy. Now that I have seen the end result I confidently predict that this movie will be remembered for the horror genre treasure that it is! Simply put, Robert Wise's The Haunting pays homage to its predecessors of gothic horror, yet breaks new ground in what has been an increasingly campy genre.

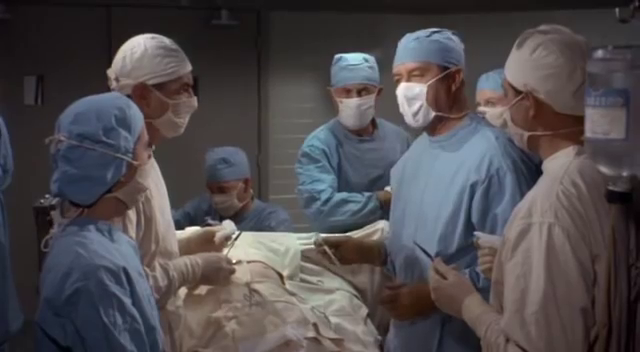

Like many horror movies before it, The Haunting sticks with the tried and true premise of a group of persons trying to maintain their grip on reality as they weather several nights in an allegedly cursed manor. Ultimately one of them snaps, but whether or not it was a mental breakdown due to desperation or supernatural forces remains the crux of the mystery. In the case of The Haunting, anthropologist Dr. John Markway leads a group of volunteers through an experiment to instigate supernatural events within the old Hill House estate for the sake of scientific discovery. They attempt to endure the terror of ghosts hauntings, cryptic messages scrawled on the walls, and subtle poltergeist events. Some more successfully than others.

If Robert Wise had left The Haunting with just these bare essentials the whole experience would have been simply average. Thankfully he and the screenplay adaptor, Nelson Gidding, did not settle for something so mundane.

Everything about The Haunting speaks to the clash of modernity versus old beliefs. All aspects of the story incorporate this battle in some way. Perhaps most blatantly we have Luke Sanderson (Russ Tamblyn), the college-boy heir to Hill House who is determined not to be put off by the house's colorful past. Stubbornly flippant and skeptical, we see that Luke is still deeply unnerved by the progressively frightening hauntings, yet unwilling to abandon the hope of turning the house into financial profit.

Richard Johnson's character Dr. John Markway holds the role of leader within the small group staying at Hill House. In speaking with Eleanor "Nell" Lance (Julie Harris) he admits that he rebelled against the idea of becoming "a practical man" like his lawyer father, instead choosing to study anthropology in combination with his long held interest in ghosts. It is his hope to further his understanding of spiritual powers by finding a logic to hauntings – to put a scientific understanding of spirituality in line with human evolution both past and future. Dr. Markway never lets go of his belief that scientific theory can be applied to Hill House, even at the end. But he does come away from the experience with a healthier respect for the forces he is toying with.

And then there is Claire Bloom's character Theodora aka "Theo". "Theo" is an enigma of a person, both guarded yet warm, and possessing either a mastery of cold reading or powerful psychic abilities. She fills the group's role of the femme fatale, and by all genre traditions should be the corrupting influence of the party who leads the men astray with her fashionable beauty and strong will. Yet Theo is not given a romantic role with either Luke or Dr. Markway. Indeed, she seems indifferent to them in an aloof, but not snide, way. Her sexuality is nonexistent, and other than regularly embracing and comforting Eleanor (who enthusiastically returns the gestures and seeks out Theo on her own at all hours of the day and night) she does not physically interact with any other character. It is also revealed that she is an independent, insightful woman who lives in her own apartment and does not have a boyfriend.

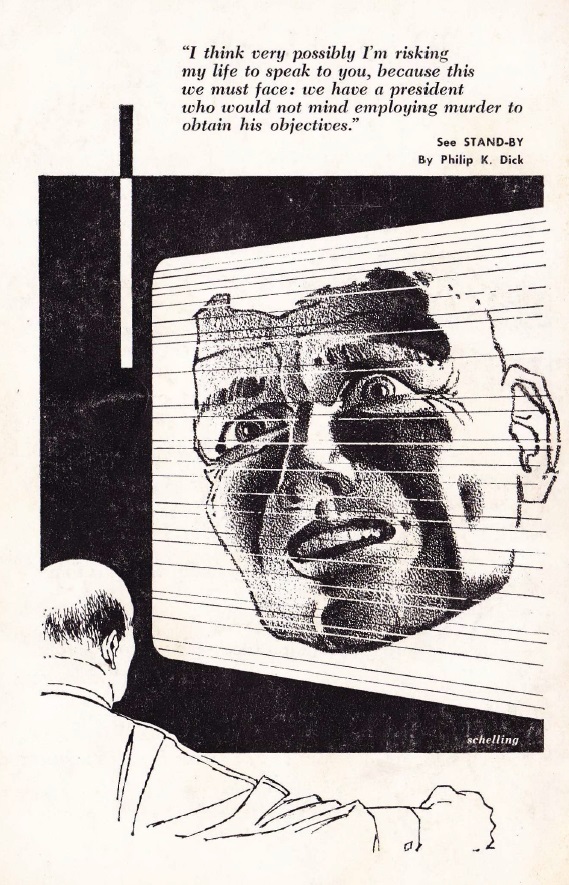

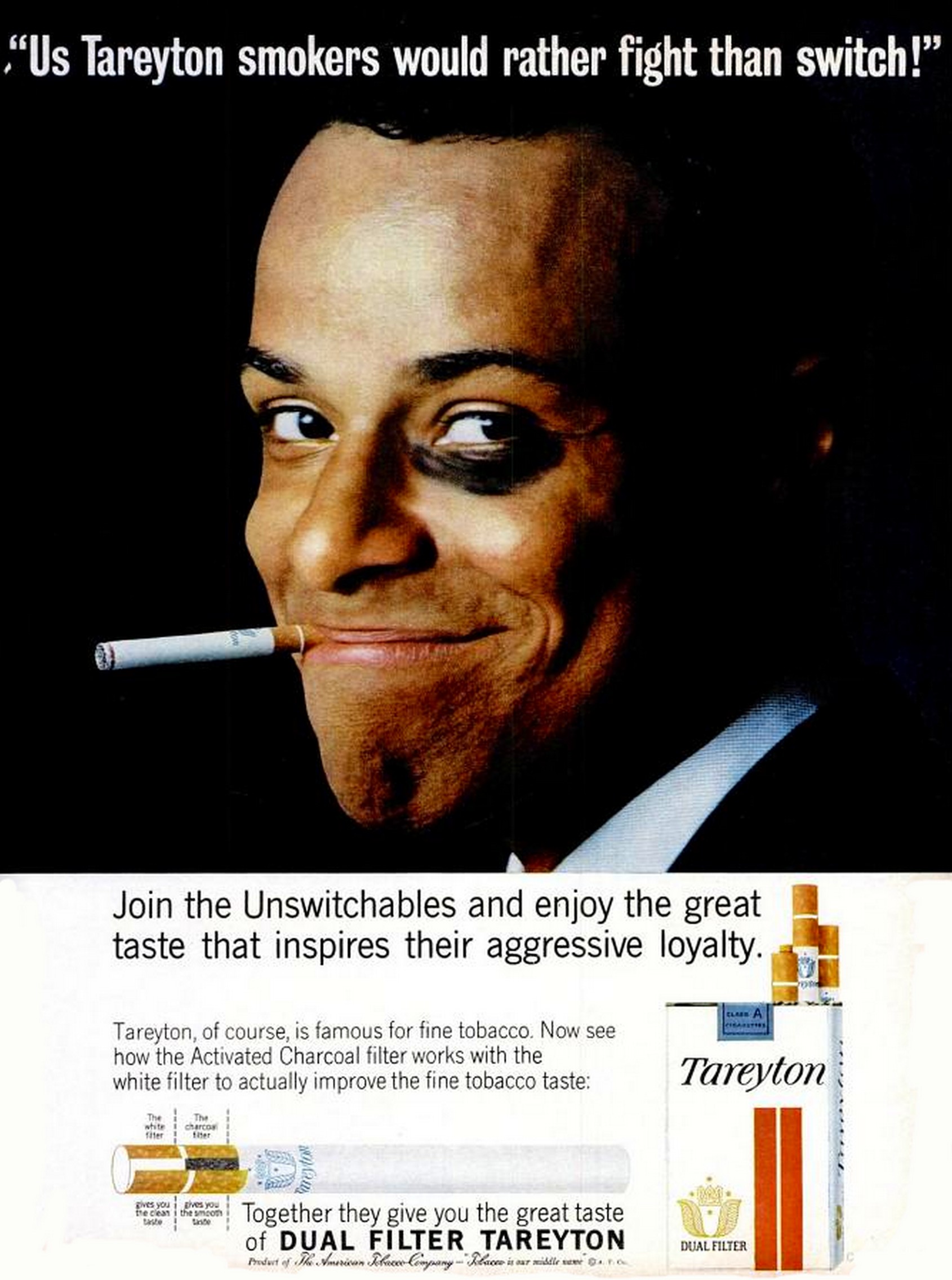

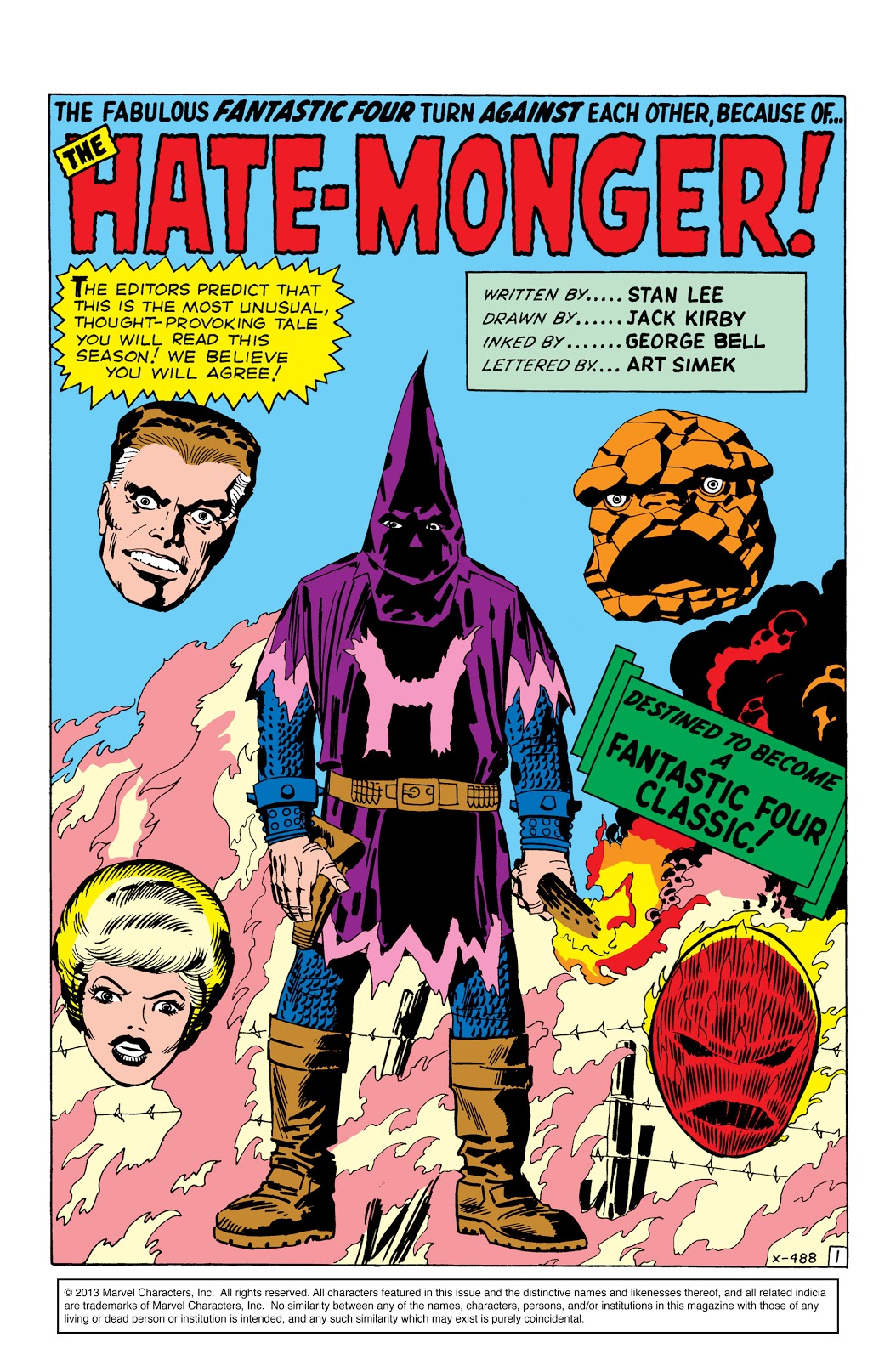

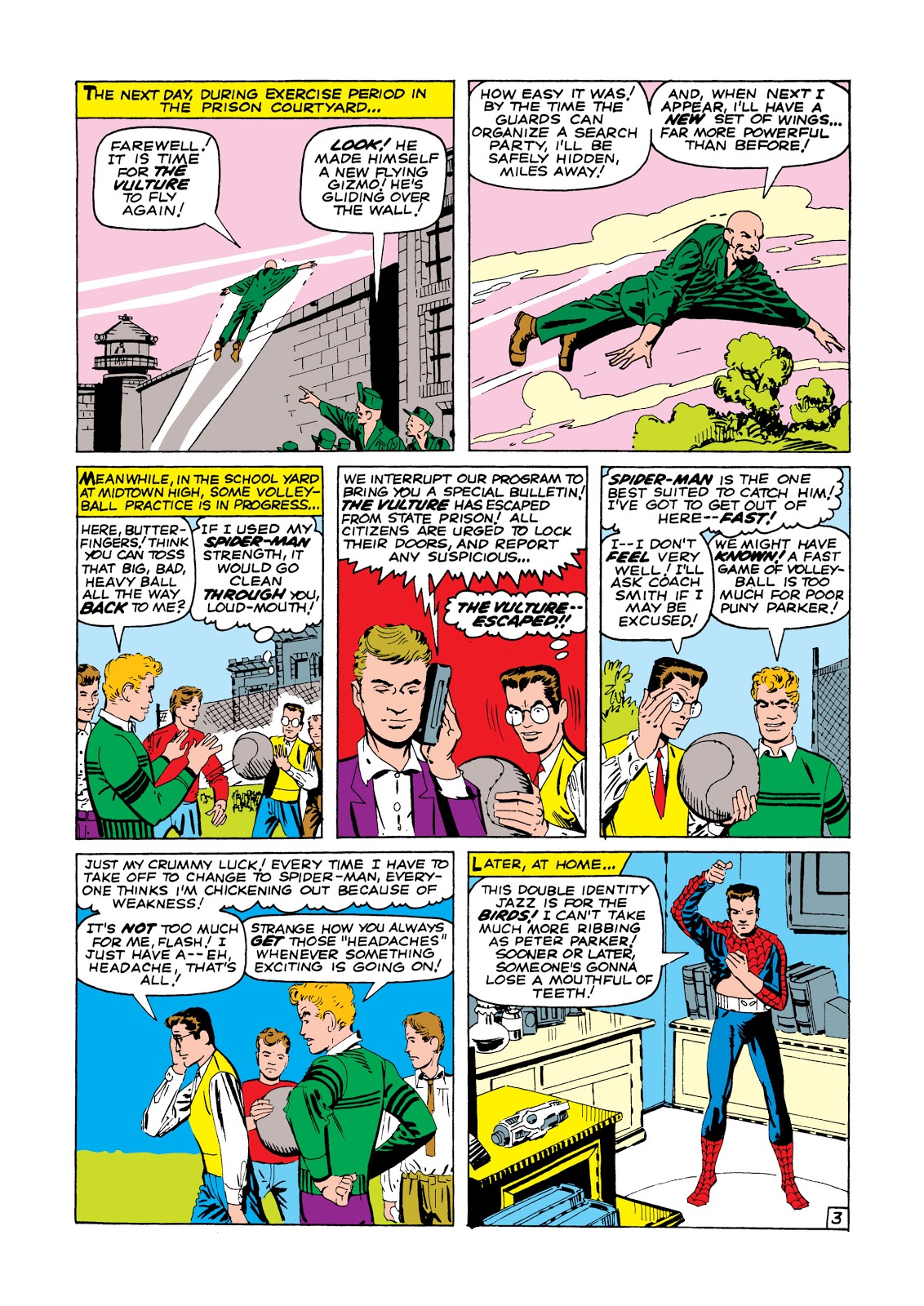

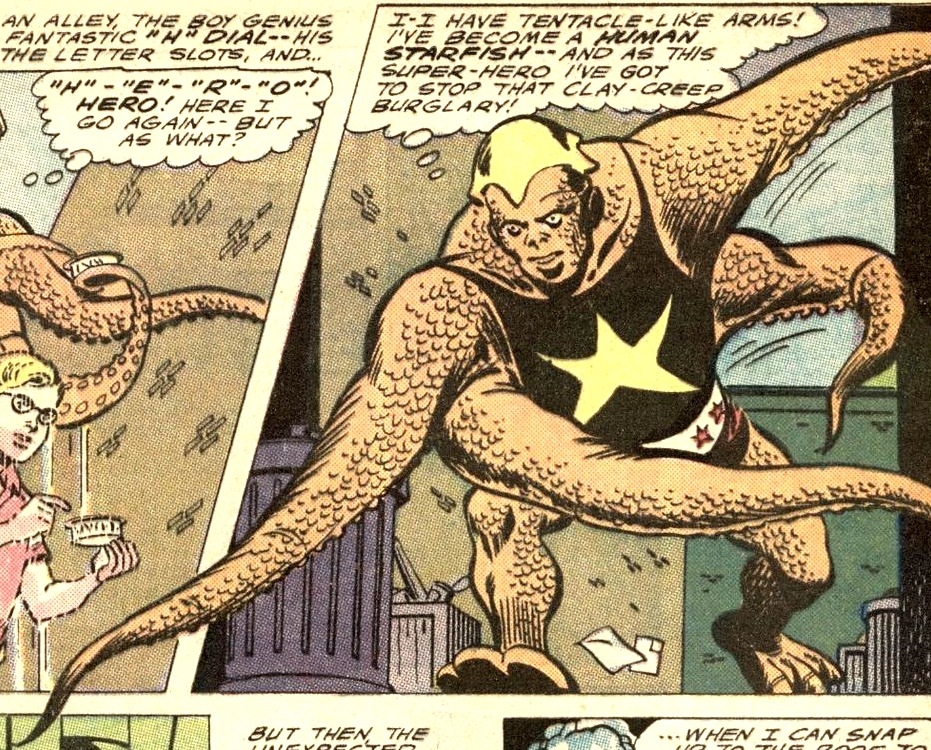

Theo is well aware of her disquieting insightfulness. Though she presents herself as confident, even indifferent, she is sensitive to how the others perceive her. She is especially hurt when Eleanor tells her that she is a "mistake of nature". Although it is implied that this could simply refer to her psychic abilities, the comradery and tension that exists in their friendship especially with regard to Eleanor’s growing friendliness toward Dr. Markway, would lead the audience to make other conclusions. Yet she continues to try to help Eleanor from hurting herself. As an implied lesbian character she is refreshingly not predatory nor joyfully cruel. She is a modern woman of many layers, and a very different queer character from other popular cultural representations that are circulating via pulp novels, comics, television and movies.

Which brings me to Eleanor Lance. Like everyone else she is a mess of mixed messages, although her story is particularly heartbreaking. Unlike the independent and powerful Theo, Nell is a frightening portrayal of what subjugation under the traditional roles of a woman can do to a person. Emotionally fragile due to a lifetime of societal isolation by her controlling mother and judgmental sister, Julie Harris' fascinatingly fills both the roles of the spinster and the romantic lead. After her mother passes and she no longer needs to serve as her caretaker, Nell is clearly left without a purpose and resented for it. She's so desperate for a shred of independence that she steals the family car knowing full well that it will mean she is no longer welcome at her sister's house. She is so starved for human connection that she simpers right up to the strangers she meets at Hill House, even though her deep rooted insecurity causes her to constantly question their dedication to looking out for her.

Nell's desire for deeper affection and understanding causes her to fall in love with the bright future Dr. Markway represents. But when she finds out he is married and is determined to "save her" by sending her away from Hill House, her mental breakdown becomes complete. If she can't find love with people, then she reasons her destiny must be with the house – to be there for it to love, to need, and to keep close. All of this culminates in the evil of the house claiming her for itself and adding her to the many tragedies it has already collected. Perhaps most heartbreaking of all is the audience's understanding that Nell never really had a chance in the first place, and will only be truly remembered as more than a passing thought by her friend Theo.

From a film theory perspective The Haunting is a daring, modern reinvention of the classic gothic thrillers which propelled Universal Studios to horror stardom in the 20s-40s, and Hammer Film Productions in the 50s. The film features a cast of classic horror film archetypes: a sheltered young woman whose romance we follow through the film, a femme fatale, a dapper and worldly man of reason, and a snide fool with more money than sense.

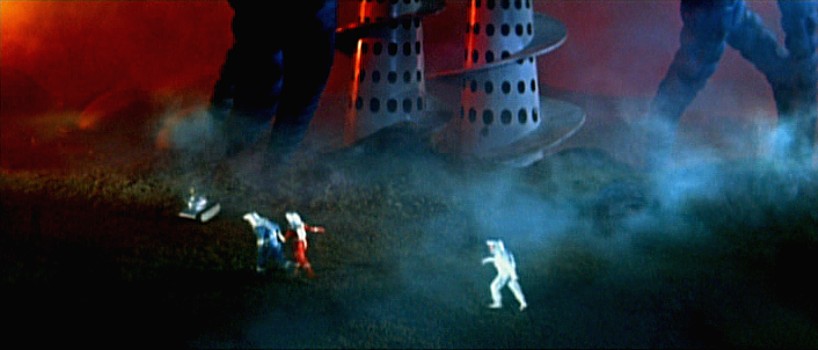

The set of the film is even faithful to the tastes of earlier horror films complete with a brooding Neo Gothic mansion decorated in opulent Rococo fit for any villainous monster or malevolent spirit. Even the story setup has resonances of earlier horror stories. In particular I would point to the paranormal investigation story thread that leads our cast of eclectic persons to gather at Hill House. We see a similar beginning in William Castle's film House on Haunted Hill (1959) and Roger Corman's House of Usher (1960), both of which likewise feature the examination of a cursed property and the doomed people within it.

But in this cornucopia of tributes to the haunted house subgenre and gothic horror in general, there is a subversiveness that is absolutely thrilling. The Haunting restlessly vibrates with a need to break away from the obvious tricks of the genre to which it belongs and create something new, and I believe that by the end of the film it does just that. Unfortunately, it seems that initial reception of the film is not wholeheartedly in agreement with me.

So far The Haunting has been received with subdued enthusiasm. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times, bemoaned the fact that the atmospheric, antique setting and chilling near-misses of Julie Harris barely kept the film afloat. Crowther concluded that the The Haunting, "makes more goose pimples than sense", and doesn't work to its gothic strengths by falling back on more classic horror moments. 1 Crowther, Bosley. "The Screen: An Old-Fashioned Chiller: Julie Harris and Claire Bloom in 'Haunting'." The New York Times [New York] 19 Sep.1963: Print.

What seems to be the most obvious missed point about such criticism is that The Haunting is not a period piece, and that a gothic setting does not come with an obligation to conform to the now cliché horror cinematography/story structure/character arcs of other haunted house stories. And really, how would doing so play better for the audience? Yes, it would give them something more familiar, but in horror unpredictability makes for a far more memorable experience. I award five stars to this atmospheric and challenging film.

[September 21, 1963] Old Horror and Modern Women (Robert Wise's The Haunting)

1963, horror, film, Rosemary Benton, Robert Wise, haunted house, The Haunting, The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley Jackson

![[September 21, 1963] Old Horror and Modern Women (Robert Wise's <i>The Haunting</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630921hauntingposter-439x372.jpeg)

![[September 19, 1963] Out of Sight (<i>The Man with the X-Ray Eyes</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630919title.png)

![[September 17, 1963] Places of refuge (October 1963 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630917cover-672x372.jpg)

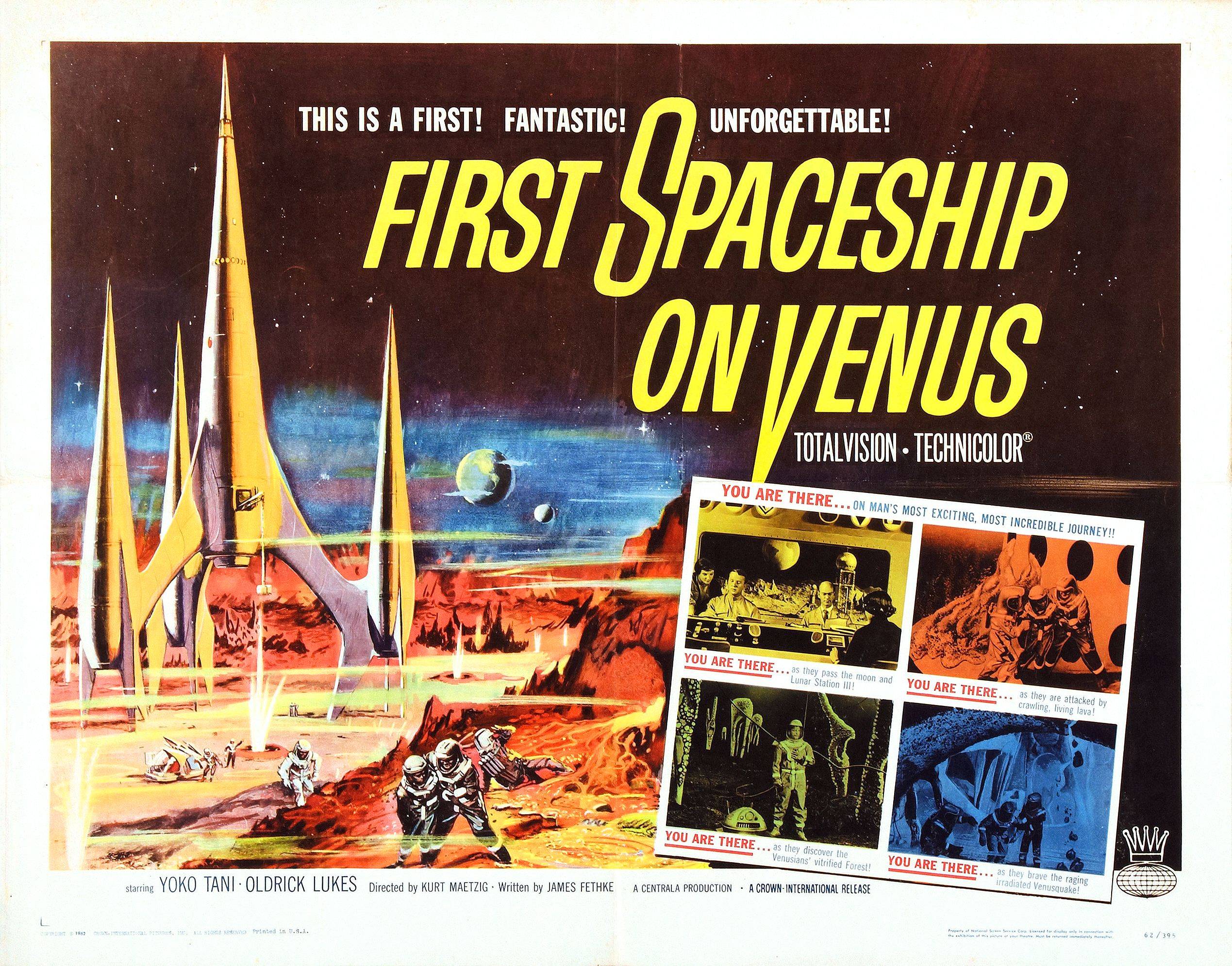

![[September 15, 1963] <i>The Silent Star</i>: A cinematic extravaganza from beyond the Iron Curtain](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630915German_poster-672x372.jpg)

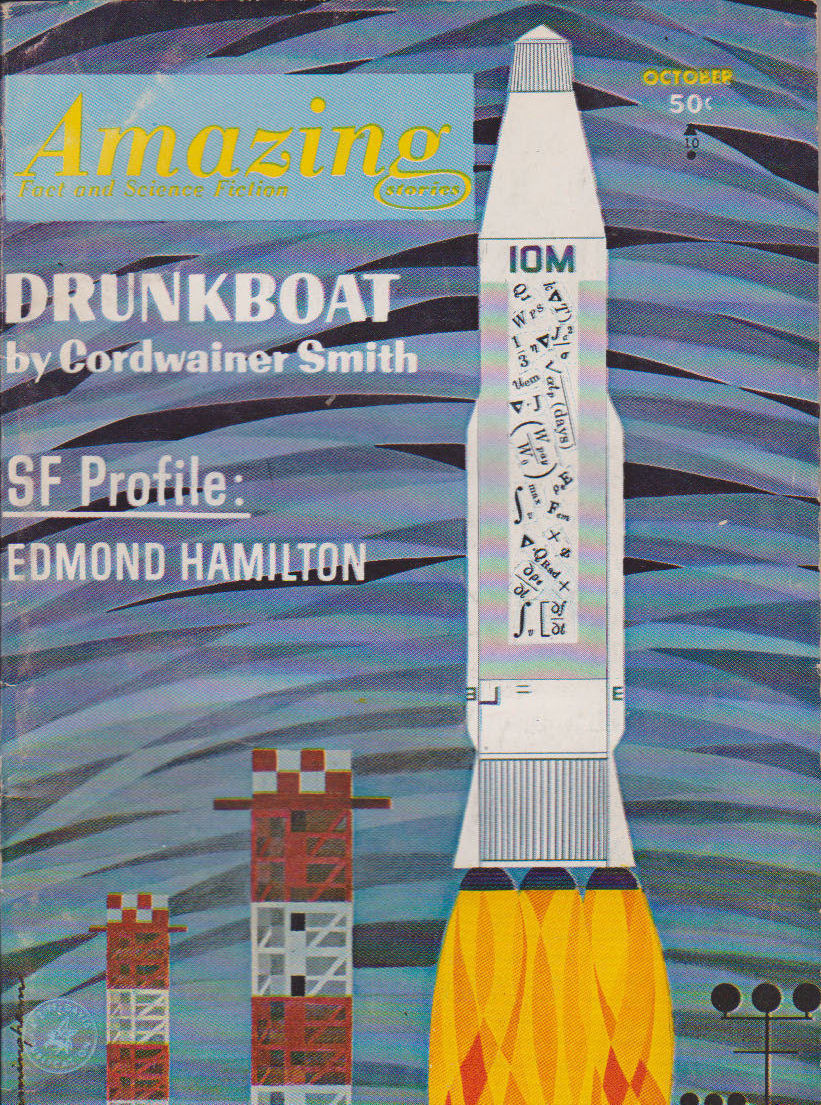

![[September 13, 1963] COMING UP FOR AIR (the October 1963 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630913cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 11, 1963] Has Marvel Comics become Mighty?](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630911ff21-cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 9, 1963] Great Expectations (October 1963 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630909cover-444x372.jpg)

![[September 5, 1963] Oh Brave New World (the 1963 Worldcon)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630902gj-640x372.jpg)

![[September 3, 1963] An unspoken Bond (Ian Fleming's <i>On Her Majesty’s Secret Service</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630902OHMSS-cover-252x372.jpg)

![[Sep. 1, 1963] How to Fail at Writing by not Really Trying (September 1963 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630831cover-672x372.jpg)