by Gideon Marcus

The New Frontier

Tomorrow, history will be made: the first Saturn V, largest rocket in the history of the world, will take off. If successful, Project Apollo's launch vehicle will be "man-rated", and one hurdle between humanity and the moon will have been cleared.

Of course, we'll have full coverage of the event after it happens, but this sneak preview makes a dandy segue. For today's article is on a literary type of explorer: Galaxy magazine. Unlike Apollo, Galaxy, which started in 1950, is a tried, tested, and even somewhat tired entity. Back in 1959, Galaxy moved to a larger, but bimonthly, format. This has not been an entirely successful endeavor, and in few issues are the problems more glaring than in this one. For if an editor needs to fill up 196 pages every other month (not to mention the 164 pages of one or two sister magazines), that editor's standards must sometimes slip…

The Old Frontier

by Gray Morrow

Outpost of Empire, by Poul Anderson

Out on the edge of space lies the mineral-poor planet of Freehold. Thinly settled by humans, and then also by the alien Arulians, it lies just outside the Empire. A growing insurgency threatens to topple the existing order, and Ridenour, an imperial troubleshooter, is sent in to monitor the situation.

by Gray Morrow

Sounds pretty nifty, but it's not. The first twenty pages of this seventy-page piece are nothing but characters explaining the story to each other. Skimming the rest of the tale, I determined that it's all more of the same. Moreover, Poul doesn't even try to disguise what he's doing. He spotlights it by having his endlessly explaining protagonist marvel at what a pedant he's being–and when other characters do the same thing, he inwardly notes how much a pedant they're being.

As Kris notes:

Rule 1 of writing: If your characters are finding what you are doing contrived, so will the reader.

The whole thing is written in that archaic style Poul reverts to when given the chance, though there's no reason to do so in this book. He also can't resist being a bit sexist, even in a story that takes place thousands of years from now. Dig this gem:

"But in the parks, roses and Jasmine were abloom; and elsewhere the taverns brawled with merriment. The male citizens were happily acquiring the money that the Imperialists brought with them; the females were still more happily helping spend it."

Because in the future, women don't work; they are parasites on the real producers–the men.

Feh. One star.

That already gets us nearly halfway through the book. Things do not immediately improve…

The South Waterford Rumple Club, by Richard Wilson

by Jack Gaughan

Aliens drop bags of counterfeit money on a small American town. Economic collapse ensues, facilitating an extraterrestrial takeover.

I was about to write that Wilson was an unknown name to me, but looking through the archives, I see he's made several appearances in science fiction magazines over the past two years. He's just eminently forgettable. This story does not change the trend. For one, he spends a couple of pages giving a history lesson as to why an influx of fake currency is such a deadly weapon–akin to anthrax and mustard gas. And then we get a tedious demonstration of such an attack, followed by a couple of pages of (not well thought out) aftermath.

This is the sort of inferior stuff that filled the lesser mags of the '50s. It doesn't belong here.

Two stars.

Thank goodness for Silverbob. From here on, out, the issue is quite good. But you have to make it to page 96! (or simply skip the dross)

King of the Golden World, by Robert Silverberg

Elena, a human, has married Haugan, chief of a tribe of aliens that lives on an island dominated by twin volcanic mounts. Theirs is a genuine love, despite their divergent evolutions, but full understanding still eludes the Earth woman. Though the mountain on which the village is sited is clearly about to erupt, Haugan seems in no hurry to evacuate his people. It is only on the eve of disaster that Elena learns the true, alien nature of Haugan's people. Will she embrace it or be repelled?

This is really quite a sensitive story, timeless and nuanced. I suspect it was influenced by Silverberg's recent nonfiction histories of the original American inhabitants (collectively referred to as "Indians").

Four stars.

For Your Information: Astronautics International, by Willy Ley

Ten years ago, it was enough to keep up with the Soviets and the Americans if you wanted to know what was up in space. These days, Earth's orbit has become a truly international province, and this month's article focuses on the efforts of the non-superpowers, of which there are many.

As a space buff, articles on satellites always score extra marks with me, so I hope our tastes are aligned. Four stars.

Black Corridor, by Fritz Leiber

A man awakens, naked, without memories, inside a featureless corridor. Ahead of him lie two doors: one is labeled "Water", the other "Air". Behind him a wall moves toward him implacably. Choose…or die.

But beyond the first pair of doors is another, and another. Is this a test? Will the test end? And what is its purpose?

Less a science fiction story and more a metaphor for life itself, this piece's worth depends solely on the execution. Thankfully, Leiber is up to the task.

Four stars.

The Red Euphoric Bands, by Philip Latham

A comet is heading straight for an Earth on the brink of atomic war. Is it our doom…or our salvation?

On the one hand, the storytelling and the science are quite excellent. On the other, the conclusion is silly. Moreover, there is a fundamental fault in this otherwise accurate piece: a comet with a two light year orbit would have a period of around six billion years–too high to serve the purposes of the story.

Thus, three stars.

Galactic Consumer Report No. 3: A Survey of the Membership, by John Brunner

The first galactic survey, conducted by Good Buy magazine, turned out to be something of a fiasco–too many beings responded, and they were just too variegated to provide anything like a profile of "an average consumer". Yet, you couldn't call the exercise less than successful…

This series tends to be silly and throw-away, but this installment I liked a lot. Why? Because it's almost like a Theodore Thomas article from his F&SF column–a couple dozen story seeds all in one piece. So many stories feature aliens that are little more than humans in costume. This one presents some real aliens. It also made me laugh a few times.

So, four stars.

Handicap, by Larry Niven

by Jack Gaughan

On the former Kzin world of Down, orbiting a feeble red dwarf, humans have established an agricultural colony. In addition to its colorful history, Down offers another attraction: the Grogs. These are comical-looking, human-sized creatures that have two phases in life. At first, they are four-legged creatures with a dog-like intelligence. In this form, they rove the deserts of Down, hunting and mating. Eventually, the females anchor themselves to a rock, where they stay the rest of their lives.

And yet, these creatures have enormous brains, suggesting a great intelligence. Why did they evolve them, and what can they do with them? Garvey, an entrepreneur whose line is making prosthetics for "Handicapped" species, ones without manipulative organs of their own (e.g. dolphins, the enormous Bandersnatchi of planet Jinx), smells an opportunity.

Handicap, like last year's A Relic of Empire, expands what is becoming a sweeping common universe, tying in the Kzinti of The Warriors, the Thrintun of World of Ptavvs, and the hyperdrive era of Beowulf Shaeffer. What I really like about Niven is that he isn't in a hurry to tell his story. There are asides and subplots, weaving a meandering course through entertaining vignettes, before tying everything together at the end. Niven's universe feels lived in, and all of its facets are interesting. That there's a nifty story at the heart of Handicap is a bonus…though my eyebrows were raised a bit by this exchange:

Garvey: "For as long as we expand to other stars we're going to meet more and more handless, toolless, helpless civilizations. Sometimes we won't even recognize them. What are we going to do about them?"

Jilson (a guide): "Build Dolphin's Hands for them."

Garvey: "Well, yes, but we can't just give them away. Once one species starts depending on another, they become parasites."

This feels a bit like an indictment of welfare, foreign aid…or assistance to the handicapped. I would not jump to concluding that Garvey's views necessarily represent Niven's views, but I also would not be surprised, as he is a hereditary millionaire, and the plutocracy often thinks ill of public demands on their wealth. I will simply note that I think Garvey is being short-sighted. Isn't it worth the investment of a little charity to create an entirely new potential market of both imports and exports? If you give away limbs to the crippled, schools to the poor, food to the starving, will they really just sit on their duffs? Or will they simply now be unencumbered members of society, ready to participate fully? I submit that equalization of opportunity through government assistance and charity actually serves capitalism rather than subverts it.

Well, that's a tiny quibble, and again, just because Garvey thinks this way doesn't mean the author does. If anything, I'm glad he gave me something to think about–along with a good story!

Four stars.

The Fairly Civil Service, by Harry Harrison

by Jack Gaughan

A day in the life of the postal clerk of the future. A particularly bad, seemingly endless day. The kind that tries a person's soul…or tests one's abilities.

Harrison is reliably good. He does not disappoint here. Four stars.

To the Black Beyond

Having trudged through a barren literary landscape for half the span of a magazine, it was comforting to have solid ground to trod for the latter half. But now that the Galaxy is done, I am once again adrift. Who knows what lies in store within the covers of the next magazine or paperback that will cross my desk? Like the expanses of space, it's all an unknown adventure.

Luckily, there are still enough treasures waiting to be found to make the journey worth it!

![[November 8, 1967] Four to go (December 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/671108cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 6, 1967] Reaching the Peak (Doctor Who: The Abominable Snowmen [Part 2])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/671106snowmenonthemountain.jpg)

![[November 4, 1967] Conflicts (December 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/IF-1967-12-Cover-672x372.jpg)

Joan Baez is arrested in Oakland.

Joan Baez is arrested in Oakland. Fr. Berrigan pouring blood into a file drawer.

Fr. Berrigan pouring blood into a file drawer. Futuristic combat in The City of Yesterday. Art by Chaffee

Futuristic combat in The City of Yesterday. Art by Chaffee![[November 2, 1967] Trouble and Toil (<i>Star Trek</i>: Catspaw)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671102title-672x372.jpg)

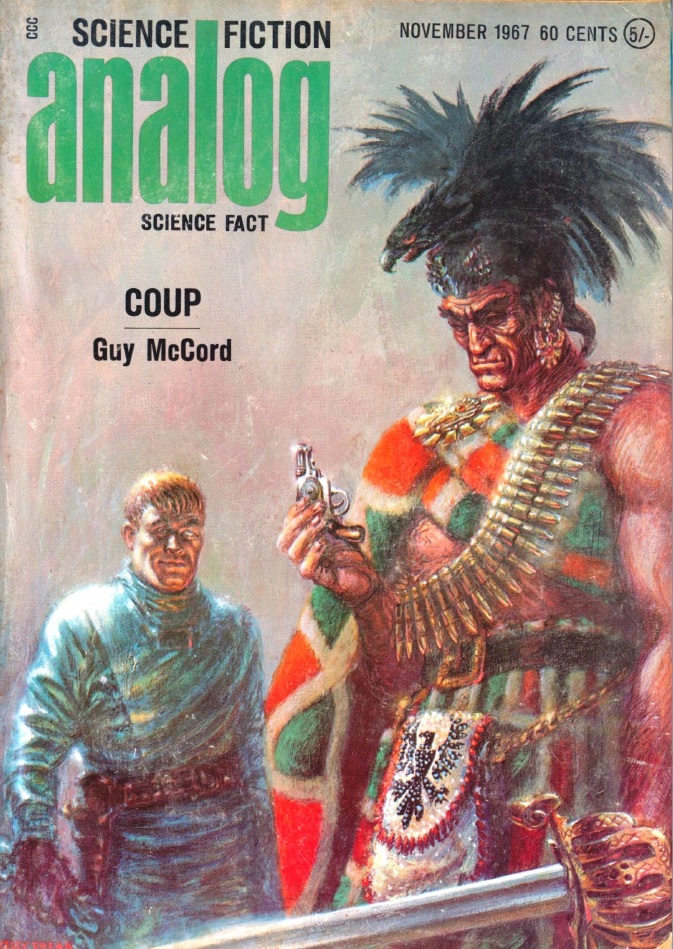

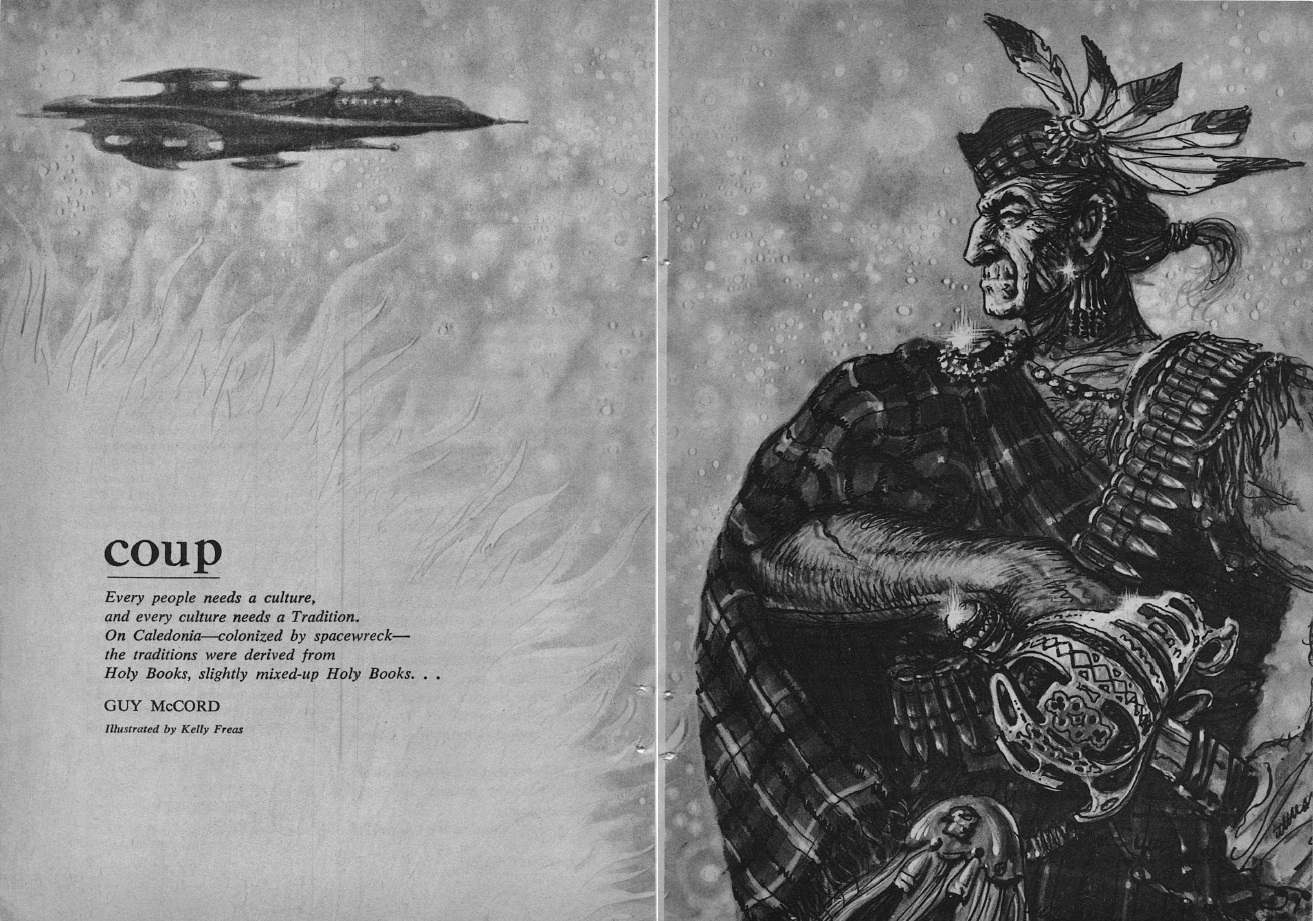

![[October 31, 1967] Same ol' (November 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671031cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 28, 1967] Unveiling Venus – at Least a Little (Venera-4 and Mariner-5)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Venus-desert.png)

![[October 26, 1967] Duet in G(ray) (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Doomsday Machine")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671026title-672x372.jpg)

![[October 24, 1967] War, Anti-utopias and Near-Future Apocalypses <i>New Worlds</i>, November 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/New-Worlds-November-1967-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Vivienne Young

Cover by Vivienne Young An example of the logic shown in this article. Not sure I understood this!

An example of the logic shown in this article. Not sure I understood this!

Example of Self's imagery.

Example of Self's imagery. Uncredited image, but it looks like a Douthwaite, who is credited in the magazine.

Uncredited image, but it looks like a Douthwaite, who is credited in the magazine. Another uncredited image that looks like a Douthwaite.

Another uncredited image that looks like a Douthwaite. Sharing the horror in full – another poetic gem – well, they seem to be liked by some!

Sharing the horror in full – another poetic gem – well, they seem to be liked by some! Illustration by Cawthorn

Illustration by Cawthorn The future of energy?

The future of energy?

An advertisement from this month's magazine that shows how different book sales and New Worlds magazine is, perhaps? How many of these authors are mentioned in detail in the magazine these days?

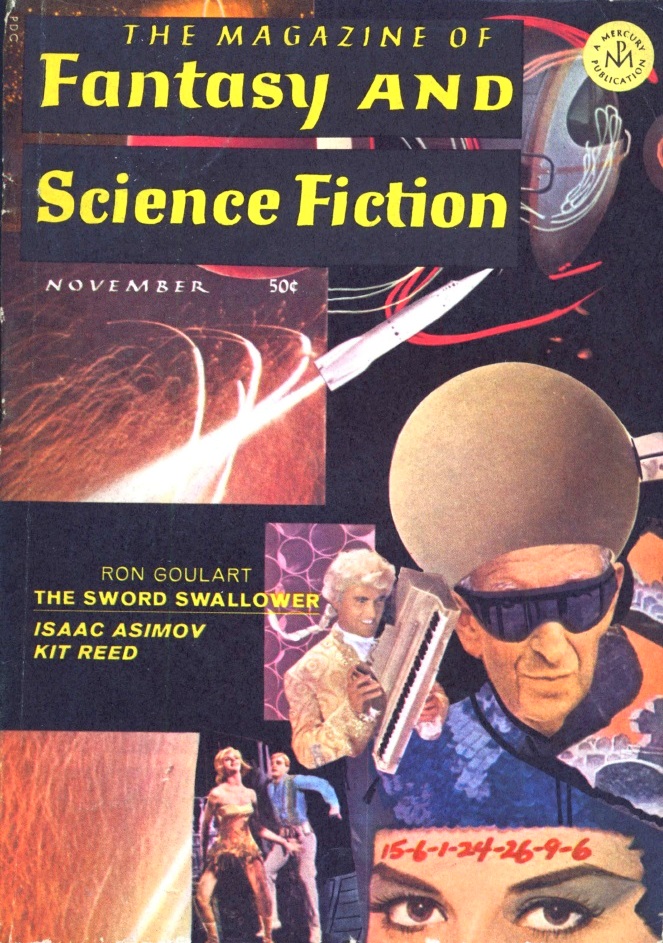

An advertisement from this month's magazine that shows how different book sales and New Worlds magazine is, perhaps? How many of these authors are mentioned in detail in the magazine these days?![[October 22, 1967] Equal Opportunity Employer (November 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671022cover-663x372.jpg)

![[October 20, 1967] Spoils the Bunch (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Apple")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671020title-672x372.jpg)