My cup runneth over!

When I started this column, I had worried that the increasing paucity of new science fiction would mean I'd run out of things to write about. Now, here we are seven months later, and I have a back-log of items on which to report. I suppose I shall just have to write constantly to get it all out. I hope you don't mind…

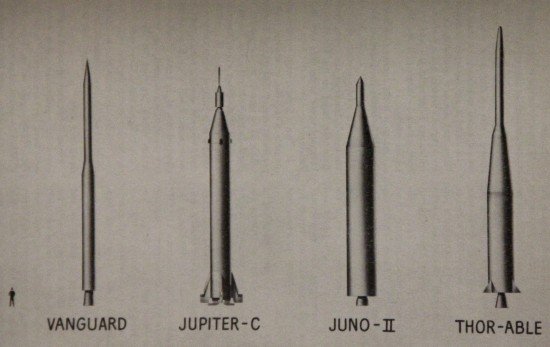

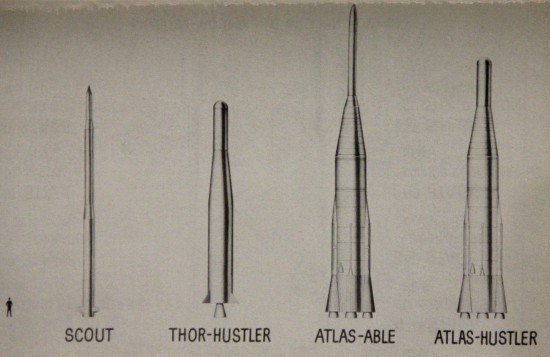

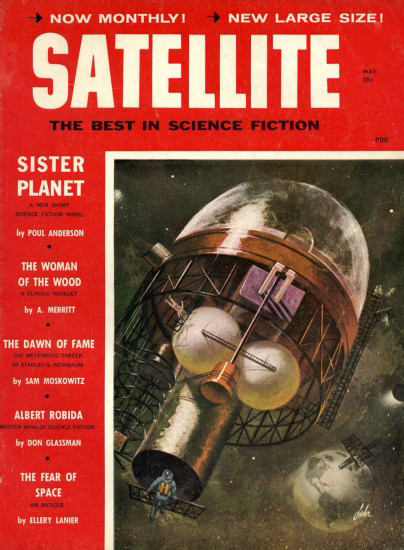

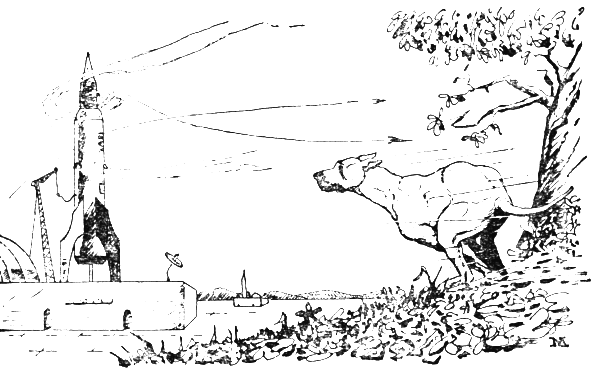

First in the queue, I wanted to wrap up the Homer Newell article I reported on five days ago, about America's new stable of rocket boosters. Last time, I talked about the new rockets expected to be in used by 1960. Now, let's press on a few more years into the future for a truly exciting sneak peek.

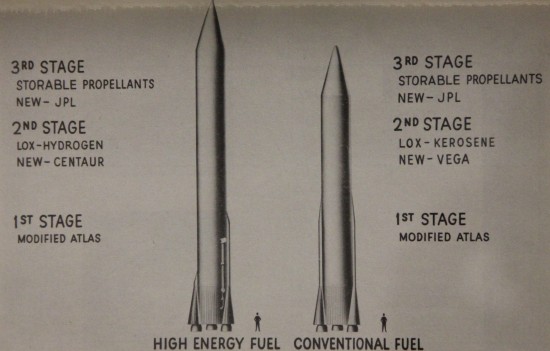

With the exception of the Vanguard and (soon-to-be) Scout, all of our space rockets are really borrowed military missiles. But as time goes on, we will see more purpose-built boosters that will be more powerful and efficient. The first true space rocket vehicles will be second stages designed to go on the Atlas ICBM, currently our biggest military missile.

The smaller of them, the Vega, is a purely civilian design that will be developed from the first stage of the Vanguard. The Atlas-Vega will to launch satellites into geo-stationary orbit for the first time. A bit of explanation as to the import of this: the Earth rotates on its axis every 24 hours. The period of a satellite's orbit is dependent solely on its distance from Earth–the closet the satellite orbits, the shorter the period. Right now, our best rockets can barely get satellites into a low orbit with a period of about 90 minutes. But the Atlas-Vega will propel satellites up to a height where the period matches the period of the Earth's rotation. This means the satellites will, to a ground observer, appear to be stationary (or at least will wobble about around a fixed place in the sky). Arthur Clarke wrote about the value of these satellites more than a decade ago; they will be way-stations for global communications.

An even bigger stage is the Centaur, which will launch truly massive payloads to the moon and to the planets. By the middle of the next decade, expect orbiting laboratories around Earth's closest celestial neighbors. To me, this is more exciting than sending a person into space, who probably won't be able to do much but give entertaining color commentary.

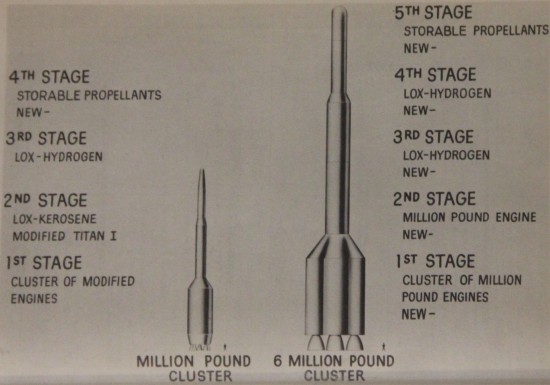

The real wave of the future is likely to be Von Braun's new brainchild–the Saturn family of rockets. These boosters are being developed completely from scratch and will be an order of magnitude bigger than anything currently in the pipeline. The biggest of them, the Nova, will be capable of landing 20 tons on the moon in one go! We may well see people on the moon by 1967.

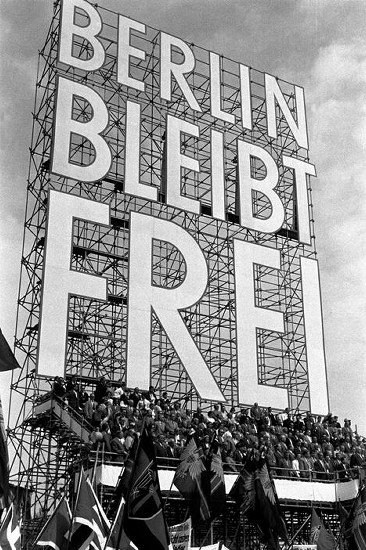

My favorite part of the article is Dr. Newell's personal appeal to us, the citizen-scientists of the nation, to send in proposals for experiments. NASA is brand-new, and they need all the help they can get to develop not just the hardware, but the ideas that will drive the creation of the hardware. It's scientific democracy and it's greatest, and perhaps it will prove an advantage over the Soviet system.

Day-after-tomorrow: Invisible Invaders! There are A-movies, and there are B-movies. This was not an A-movie. The popcorn was yummy, though!

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.