[Today is the last day to get your Worldcon membership! Register here to be able to vote for the Hugos.]

by Cora Buhlert

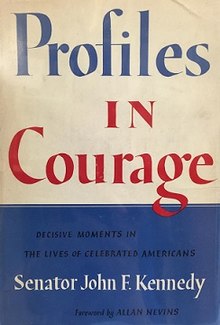

The Newest from Andre Norton

1963 is almost history and here in Germany, I'm getting ready for New Year's Eve. I have friends coming over, a bowl full of spaceman's punch, plenty of nibbles, champagne in the fridge, a record player with all the latest albums and fireworks to welcome the new year.

I've been a good girl and so Santa brought me presents, including science fiction paperbacks from the US. I dug into one of the books right on Christmas Eve, even before Gruß an Bord, a radio program sending greetings to the crews of German ships around the globe, had finished.

That book was Ordeal in Otherwhere by Andre Norton, whose real name is Alice Marie Norton. I've heard of Norton before, right here at the Journey, but so far I've never read anything by her. Time to rectify that.

Ordeal in Otherwhere is the sequel to a novel entitled Storm over Warlock. I haven't read it, though Terra – Utopische Romane ran a translation last year. Not that it matters much, for Ordeal in Otherwhere is perfectly understandable, even if you haven't read the earlier book.

The story, in brief

The novel starts with our protagonist, a young lady named Charis Nordholm, on the run. Via flashbacks, the reader learns that Charis came to the colony world Demeter with her father, a government education officer. The colonists, a religious cult, were wary of the government and considered Charis "unfemale" because of her education. Then disaster struck in the form of a plague, which first killed the government agents, including Charis' father, and then spread to the colonists, hitting only men and post-pubescent boys. The superstitious colonists blamed the government and hunted down survivors like Charis.

With any other author, this religion versus science conflict would have been the story, for there is certainly novel's worth of material here. And indeed, I wonder whether Andre Norton wrote that novel elsewhere. But here, the events on Demeter are merely background, By chapter two, Charis has left Demeter behind, never to be seen again except in a dream sequence. Though I wonder what became of the colonists and if they survived.

Charis' salvation come in the form of a dodgy trader whose rocket ship just happens to land at the very moment Charis is recaptured. The trader sells indentured workers to the colonists in exchange for Charis. A teenaged girl indentured to a space captain of questionable morality raises all sorts of unpleasant possibilities. But Norton's books are marketed as juveniles and so Charis' virtue remains intact. The trader sells Charis to the merchant captain Jagan who miraculously has no unsavoury designs either. Jagan has a trading permit for Warlock, a planet inhabited by matriarchal aliens, the Wyvern. The Wyvern refuse to negotiate with men, so Jagan needs a woman. The first one went mad, so now it's Charis' turn.

Charis manages to send a message to a government outpost on Warlock. But before help can arrive, she finds herself compelled to walk across Warlock to meet the Wyvern. En route, Charis also finds a friend, the curl-cat Tsstu. There is a dreamlike, almost psychedelic quality to Charis' journey. Andre Norton has a gift for evocative descriptions of alien landscapes, which she employs to full effect here.

Charis' sojourn among the Wyvern, who teach her telepathy and teleportation, is brief, then Charis uses her newfound abilities to return to the trading post, only to find it destroyed, everybody inside dead. However, Charis also meets a new allies, Survey Corps cadet Shann Lantee and his pet wolverine Taggi. Shann is the protagonist of Storm Over Warlock. He is also – and that's sadly still remarkable even in our otherwise progressive genre – described as a black man. Alas, the cover – an otherwise accurate illustration of Charis, Shann, Tsstu and Taggi – completely ignores this.

Shann believes pirates are responsible for the attack on the trading post. However, a mysterious spear found on site points at the Wyvern. Both theories are sort of correct, because outlaws have freed Wyvern males from female control and are using them as muscle. In retaliation, the Wyvern females want to attack all humans. Only Charis can prevent this.

After many travails, Charis finds Shann a prisoner of the Wyvern, unresponsive and trapped inside a dream. Joining forces with Taggi and Tsstu, Charis enters Shann's dream prison and breaks him out. In the process, a mental bond is forged between all four of them.

It turns out that the pirate attack is a corporate takeover. A company has sent mercenaries to gain control of Warlock.The mercenaries have taken over the government base. They also have a device that can nullify the Wyvern’s power. And only Charis, Shann and their animal companions can stop them.

Shann is taken prisoner once more, but Charis escapes and warns the Wyvern and Shann's boss Ragnar Thorvald. But the plan to retake the base hinges on Charis, who stumbles into the base, babbling about snakes. The mercenaries take her to the medbay, which conveniently is also where Shann is held, catatonic in an attempt to avoid interrogation. With help from Tsstu, Taggi and his mate Togi, Charis manages to revive him.

The novel culminates in a standoff between Charis, Shann, Taggi and Tsstu on one side and the Wyvern males on the other. Shann and Charis broker a peace between the Wyvern males and females, so no one can exploit the rift between the sexes (which makes me wonder how they manage to reproduce) anymore.

Thorvald is impressed and drafts Charis as well as Tsstu and Taggi into service. Charis doesn't mind, because by now she has become fond of Shann and not just because of their mind link either.

My Observations

Charis is a likable protagonist, a smart and resourceful young woman of the kind that is still too rare in our genre. She spends much of the novel reacting to events, but towards the end, Charis is clearly in control and even Thorvald must bow to her will. Charis also rescues Shann repeatedly.

Unfortunately, Charis is the only competent human female we encounter – all others are either aliens, animals, nameless colonists or Charis' crazed predecessor. Besides, neither the government nor the villainous corporation consider sending women to Warlock, though that's a no brainer. In many ways, human society or what we see of it is the polar opposite of Wyvern society, a world where men hold all the power and women, particularly educated women like Charis, are a rarity. In fact, I wonder if Norton wanted to make just this point or whether she unconsciously defaulted to genre conventions.

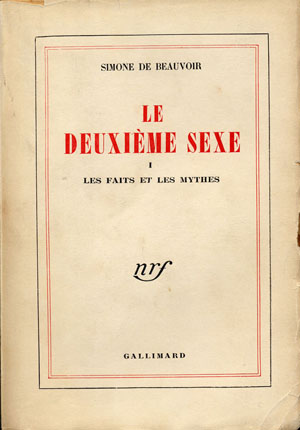

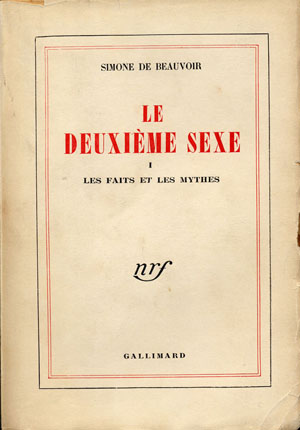

The genuinely alien Wyvern are neither portrayed as pure menace nor as beyond reproach – after all, the females control the males and consider them mindless brutes incapable of rational thought. The portrayal of an alien society where the rift between males and females is so great that they barely seem part of the same species brings to mind books such as Le Deuxième Sexe (The Second Sex) by French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir or The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan, both of which diagnose the same problem in our society. I have no idea whether Andre Norton has read either book, but Ordeal in Otherwhere almost feels like a response to these and similar works.

Ordeal in Otherwhere is science fantasy rather than science fiction. There are spaceships and blasters, but Norton never gives much detail about either. Even the nullifier, the device on which the plot hinges, is never described nor do we learn where it came from. Meanwhile, "the Power" is basically magic, controlled via mystical symbols. Norton even acknowledges this, since the Wyvern females are referred to as witches throughout the novel. This seems to be a recurring theme with Norton, as her earlier novel Witch World shows.

The hint of romance between Charis and Shann feels like an afterthought. True, Charis is quite taken with Shann from their first meeting on and worries much more about him than she ever thinks about her late father. We don't know Shann's feelings, because we never get any insight into him; Charis is the sole point-of-view character. Nonetheless, the romance feels oddly chaste. There is no kiss, let alone more. Holding hands is as far as Charis and Shann go. Even when Charis searches the unconscious Shann for useful items or when they sleep huddled together in a cave, Shann's head resting in Charis' lap, there is no hint of physical passion. This total lack of sex is not limited to Charis and Shann either – absolutely no one in this novel, whether human or Wyvern, seems to have sex with the possible exception of Taggi and Togi, since they have cubs.

I'm no big fan of animal companions, since they often seem too anthropomorphic. However, I really liked Tsstu and Taggi. Both are fully rounded characters in their own right, yet it's clear that their thought processes are very alien, when Charis links with them. Animal companions seem to be another recurring theme with Andre Norton. At one point, Charis asks Shann whether he is a Beastmaster, which happens to be the title of an earlier Norton novel. Coincidentally, I had to look up what sort of animal a wolverine is. I had assumed a wolf-like creature, but it turns out a wolverine is what we call "Vielfraß" (eats a lot) in German.

Summing up

Overall, I enjoyed Ordeal in Otherwhere, though there are some issues with the novel. The plot moves at a brisk pace, so brisk that I occasionally had to flip back to check if I hadn't accidentally skipped a page or two. There is easily material for two or three novels here and so Ordeal in Otherwhere feels rushed. Nonetheless, I will seek out other books by Andre Norton.

An enjoyable adventure in the grand old planetary romance tradition. Four stars.

Happy new year, from all of us at the Journey! Here's to a bright 1964…

![[January 14, 1964] Out Of The Frying Pan (Dr. Who: <i>The Daleks </i>| Episodes 1-4)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640114plungerofdoom-672x372.png)

![[January 12, 1964] SINKING OUT OF SIGHT (the February 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640112cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 10, 1964] Journey to the Stars, Journey into the Self (<i>Starswarm</i>, by Brian Aldiss)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1964] A Taste of Homely (February 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640108cover-570x372.jpg)

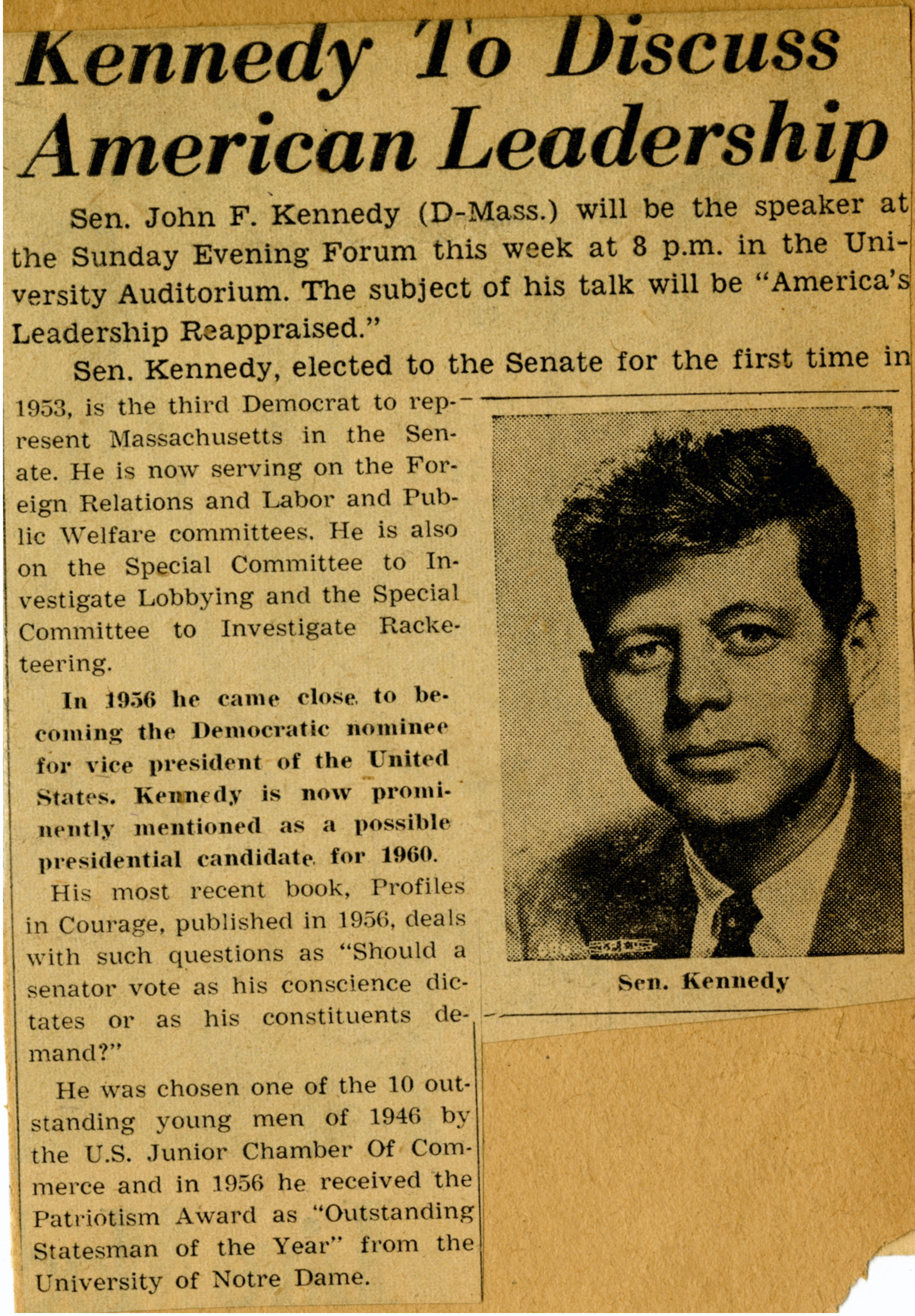

![[January 6, 1964] JFK & me](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640104arelnkennedy-672x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1964] Something borrowed, something blue (Ace Double F-253)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/640106f253-1-672x372.jpg)

![[January 2, 1964] All's well that ends well (January 1964 <i>Analog</i> science fiction)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640102cover-653x372.jpg)

![[December 31, 1963] A not unpleasant ordeal (<i>Ordeal in Otherwhere</i> by Andre Norton)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631231Cover_Ordeal_in_Otherwhere-419x372.jpg)

![[December 29, 1963] Meet the Unknown (<i>Twilight Zone</i>, Season 5, Episodes 9-12)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631229b-672x372.png)