by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

Although only bi-annual, rather than quarterly, at the moment, Carnell continues to regularly release his anthology series, easily eclipsing Pohl’s Star series and Knight’s Orbit. Will it be lucky #13?

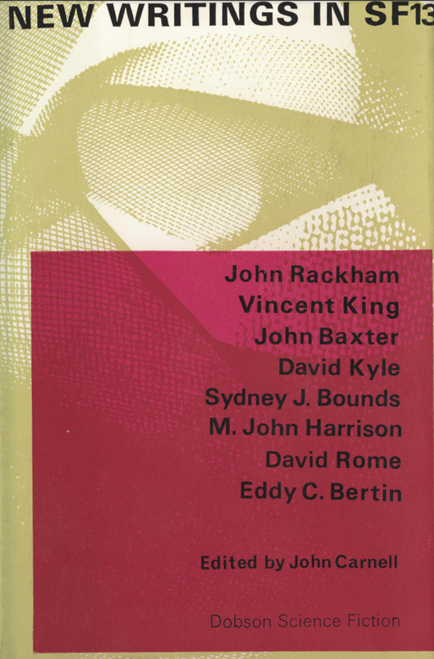

New Writings in S-F 13

Carnell notes there is an international flavour to this volume, with four Brits, Two Aussies, One American and One Belgian. Has any English Language SF publication series managed to have a male Belgian author before a woman author of any nationality? I think it may be a first! (International SF had both in its second issue.)

The Divided House by John Rackham

Leaving in 1984 on a ten-year voyage to look for intelligent life, Space-Farer IV now returns (due to time compression) in 2104. They find an Earth divided by genetics between the ruling Croms and their slaves, the Nandys, and the crew are split into the different camps.

I recently saw Judgement at Nuremburg on the BBC and this brought to my mind a scene where a witness on the sterilization procedure says:

My Mother…She was a hardworking woman, and it is not fair what you say. Here. I want to show you. I have here her picture. I would like you to look at it. I would like you to judge. I want that you tell me, was she feeble-minded? My mother! Was she feeble-minded? Was she?

This story addresses the question of eugenics, how we can judge one type of person to be inferior to another and how easy it is for science to be perverted. Important ideas.

And yet, I am not 100% sure I understand the conclusion he is meant to be reaching, nor the way in which it is delivered. I suspect this may be a story Rackham is planning to expand to novel length.

Three Stars for now.

Public Service by Sydney J. Bounds

On a densely populated island city, the fire service are reduced to a policy of containment instead of stopping fires. The poor are crying out for change, but what else can Fire Control do?

Reading this, I wondered if it was inspired by Kowloon Walled City, where the lack of access roads make it impossible for fire vehicles to enter. As such, it felt believable even in its exaggerated fashion, and Bounds put it together with great style. Dark, atmospheric but an all too realistic vision of the future.

Four Stars

The Ferryman on the River by David Kyle

The tower platform is a common site from which people throw themselves to their death. Hector is a salvager who takes away those who jump and offers them a new life. But is he salvation or slaver?

This is very much a stylistic piece, so your opinions will likely depend on how you feel about a regular switch between long run-on sentences full of descriptions and short clipped statements, in other words, how I write. I like it.

Four Stars

Testament by Vincent King

The Exploration Corps travel to 3m2t670, the last unexplored planetary system in the galaxy. Their mission, to determine if any other world has ever evolved life. We hear the record of Officer Dahndehr as his apparent discovery of the remnants of an ancient civilization turns to disaster.

King has tended to specialize in Vancian Medieval Futurism, but he manages to do well here in more common SFnal settings. It is a touch old fashioned, like a combination between Clarke and Ashton Smith, but he adds a unique style to it and has a twist in the tail I did not expect. Well done all round.

Four Stars

The Macbeth Expiation by M. John Harrison

On an unexplored planet an expedition shoots a group of alien beasts. When they return to the site, however, there is no sign of the encounter. Did they fail to hit them? Were they hallucinating in the first place? Or is something stranger going on?

This is described as a psychological thriller, and I would say that is accurate. It is a fairly atmospheric example, which makes us question what is real, albeit an unexceptional one.

A high three stars, probably a fourth for those who really enjoy the subgenre.

Representative by David Rome

Catton is an insurance salesman who is annoyed by his young neighbours, The Brownings. They laugh off his sales attempts and are convinced they will never need it. However, upon discovering a near identical couple have moved in next to his friends, he suspects something stranger is happening.

This is another example of what I term “Exurban Uncanny”, which often turns up in New Writings, unnerving stories about the sterileness of new towns. This is a pretty good story of this type, if rather obvious.

Three Stars

The Beach by John Baxter

People live in the warm embrace of the beach. Swimming, partying and in full contentment. One day Jael suddenly notices that buildings exist beyond the beach and leaves to investigate.

I am not sure what to make of this. Is it meant to be a mockery of surf bums? A stylistic experiment? An exploration of how people cope with trauma?

Whatever it is, Baxter writes it well enough to earn Three Stars.

The City, Dying by Eddy C. Bertin

In breathless and experimental style, Bertin tells of Wade’s attempts to find meaning whilst living in a police state. But, in such a place, what is reality and what is nightmare?

Apparently, this was originally written for a Belgian literary contest, then translated into Dutch and further into English, revised by the author each time. However, you wouldn’t know it. It reads incredibly well and makes use of the kind of typographical experiments en vogue in New Worlds.

Yet, it doesn’t feel like it is doing anything particularly new; rather it is what might happen if Kafka had submitted a piece to Michael Moorcock.

A high three stars

Keep Calm and Carry On

So, overall, this was a pretty solid volume of his series. Nothing that would rise to an all time classic but nothing I did not find interesting to read. Will the series continue its success? Given the British John C. has been editing SF publications for just as long as his American counterpart, I don’t see either of them putting down their red pens any time soon.

by Victoria Silverwolf

Laughing to Keep From Crying?

The latest Ace Double (H-91) contains two short novels (probably novellas, really) with plots that seem comic, at first glance, but are treated mostly in a serious manner. Let's take a look at them.

Murphy's Law

The shorter of the two presents a situation in which anything that could go wrong does go wrong.

Target: Terra, by Laurence M. Janifer and S. J. Treibich

Cover art by Jack Gaughan.

Some folks are inside a space station carrying nuclear weapons to be used against the Enemy should war break out. Our hapless hero, Intelligence Officer Angelo DiStefano, has to deal with artificial gravity that changes from zero to three times Earth normal, and everything in between, at random. His magnetic boots wander around on their own. The food machine produces inedible stuff that looks like weirdly colored snakes.

Bad enough, but when he finds out that the station's weapons are aimed at every major city on Earth, Good Guys or Bad Guys, he's got real problems.

So far, the story seems like a black comedy farce. I was taken by surprise, therefore, when an expository chapter reveals that the majority of Asians died in a plague that didn't harm non-Asians. Not exactly funny. Anyway, that's got something to do with the surviving Asians getting ready to attack the others, which will cause the station's missiles to launch.

(I should mention that the station has run out of sex suppressant, so the only woman aboard has a paranoid fear of being raped. Sorry, I'm not laughing.)

Angelo tries to figure out who's trying to wipe out all life on Earth. Aliens? A mad saboteur? And what can be done to prevent total Armageddon?

There's a lot of quirky characters, from a "midget" electronics genius to a captain who never leaves the bridge. Besides the distasteful content I mentioned above, there's also another armed space station containing Africans. The implication that there's a sort of racial Cold War going on doesn't fit very well with the silly slapstick that starts the story.

Two stars.

Far Out Music

The other, slightly longer, half of the book features a musical group set on going where no one has ever rocked and rolled before.

The Proxima Project, by John Rackham

Cover art by John Schoenherr.

Horace McCool is a rich guy who is obsessed with the band's female singer. The members of the Trippers call themselves Jim, Jem, Johnny, and Yum-Yum. Nobody knows their real names, or anything else about them.

Horace wants to marry Yum-Yum, even though he's never even met her. When he manages to make his way backstage during a concert, she's not interested at all. (Her utter disdain may be best demonstrated by the fact that she casually strips nude in front of him in order to take a shower.) Unable to take a very firm No! for an answer, Howard gives her a gift that has a tracking unit hidden in it. With his loyal secretary, who has her own crush on one of the male members of the group, Horace follows Yum-Yum and the others to a mansion on the Moon, and then much further.

Sounds like a romantic comedy, doesn't it? And yet there's a serious tone to much of the story. The four members of the Trippers are super-geniuses who only started the band so they could raise enough money for their secret project. They're cynical about the rest of the human species, and just want to get away from Earth forever, even if it means a seemingly suicidal one-way voyage.

Horace's mad passion seems way out of character for an otherwise sensible fellow. The climax of the story strained credibility to the breaking point. I suppose the author might be saying something about the worship of celebrities and the Generation Gap, but it's not a profound work in any way.

Two stars.

A is for Anywhere

Next on my reading list is a book that takes its two protagonists on another wild journey, but not into outer space.

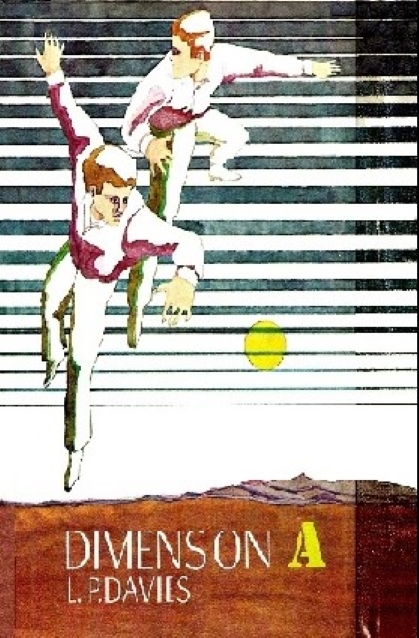

Dimension A, by L. P. Davies

The narrator is a teenage boy who gets a message from a buddy of the same age. It seems that the other fellow's uncle disappeared, along with his mysterious helper. Enlisting the aid of a scientist, for whom the narrator works, they try to figure out what happened.

Not much of a mystery, really, because we find out right away that the uncle was working on a way to reach a parallel reality known as (you guessed it) Dimension A. (Does that mean our own universe is Dimension B?)

What with one thing and another, the two kids accidentally land in Dimension A, and don't see a way back. They have to deal with hallucinations created by an unseen entity behind a green mist, as well as primitive humans who somehow manage to have ray guns. Can they find the missing uncle and make their way home?

The novel seems intended for younger readers, mostly because of the age of the two main characters. The language isn't overly simple, and adults of any age can read it without feeling they're being talked down to. The book doesn't try to be anything but an imaginative science fiction adventure story, and it succeeds at that modest goal.

Three stars.

New and Improved?

Two well-known writers recently published expanded versions of earlier works.

Into the Slave Nebula, by John Brunner

This is a revision of one half of an Ace Double from 1960. (D-421, to be exact. The other half was Dr. Futurity by Philip K. Dick.)

Cover art by Ed Emshwiller.

I haven't read it, so I can't compare it with the new version.

Cover art by Kelly Freas.

At some time in the far future, Earth is a place of wealth and leisure. Robots and androids (artificially grown humans, with blue skin to identify them) do the work, while other folks enjoy themselves.

(There's a brief mention of people who have lost their wealth through foolish behavior. They're known as the Dispossessed. Otherwise, poverty doesn't exist.)

During a time of wild celebration, the protagonist stumbles across an android who has been severely beaten and maimed. Another android, knowing his fellow slave can't survive, puts him out of his misery with an injection. The protagonist is horrified by what happened to the dead android, but it's just considered destruction of property instead of murder.

(Given the different skin color of the android and their legal position in society, an analogy with American slavery prior to the Civil War seems likely.)

Adding to the mystery is the discovery of a dead man nearby with a knife in his chest. A police detective comes by, but doesn't seem very interested in solving the case.

The surviving android, noticing that our hero is sympathetic, slips him an item taken from the dead man. It reveals that he was a very important person everywhere but Earth. This sends the protagonist on a journey to several different colonized planets, where he learns the dark secret behind the manufacturing of the androids. Along the way, people keep trying to kill him.

(There's a plot twist that made me want to call the book Blue Like Me, but that seemed too frivolous.)

Not in the same league as the author's groundbreaking masterpiece Stand on Zanzibar, but a competent science fiction novel.

Three stars.

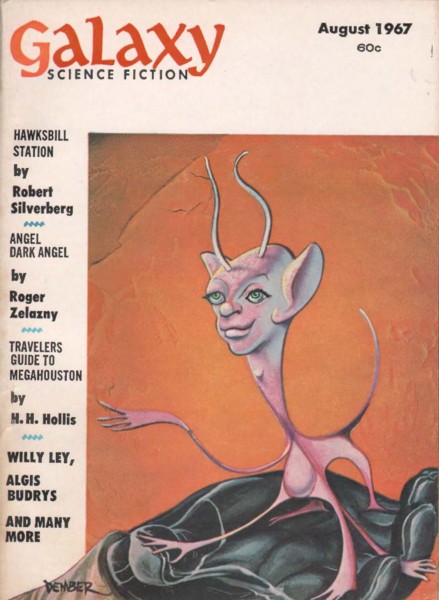

Hawksbill Station, by Robert Silverberg

The novella Hawksbill Station appeared in the August 1967 issue of Galaxy.

Cover art by Sol Dember.

The Noble Editor gave it a positive review when it first appeared. Will the novel be better, worse, or about the same?

Cover art by Pat Steir.

In the twenty-first century, the United States is under a totalitarian (but superficially benign) government. Capital punishment is banned, but political prisoners are sent back in time about one billion years. Since travel to the future is impossible, this is equivalent to a life sentence.

The protagonist is the de facto leader of the exiles. (All male, by the way; there's another prison colony for women millions of years apart from the men. The novel never visits the female prisoners, and that might make for an interesting sequel.) He's more or less sane, unlike many of the other guys. One is trying to make a woman out of mud. Another is trying to use ESP to escape. Yet another attempts to contact aliens.

The situation changes when a new prisoner arrives. He's younger than usual, for one thing. More telling is the fact that he claims to be a economist, but doesn't known a darn thing about economics. What is he doing here?

If you've read the novella, you know that's the same plot. What's been added is a series of flashbacks, showing how the main character became a revolutionary and how he was betrayed and imprisoned. (These sections also feature the novel's only female character. She doesn't show up too much, but her fate adds a certain poignancy.)

The flashbacks make the character and the world in which he lives seem more real, but they're not absolutely necessary. Whether you prefer the leaner novella or the richer novel is a matter of taste. There isn't a big difference in quality, if any.

Four stars.

by Gideon Marcus

The Spawn of the Death Machine, by Ted White

Ted White has done it again…in more ways than one.

Some of you may remember Rosemary Benton's stellar review of Android Avenger, in which she gave five stars to the tale of Bob Tanner, a cyborg and revolutionary in a staid, computer-run future.

In the luridly (but appropriately) titled Spawn of the Death machine, Bob Tanner is back, and so is Ted White in fine form.

First, a little background, from the horse's mouth:

SPAWN was sold originally to Paperback Library, but was not my first submission to them (through my agent). The first book I submitted to them (in outline) was BY FURIES POSSESSED. They said they were looking for an Ace-Book-type book, so I figured, wothell archy, how about the sequel to an Ace Book? Which SPAWN is, being the sequel to ANDROID AVENGER (original title, changed by Don Wollheim, was THE DEATH MACHINE). That they bought.

The cover of the original edition of SPAWN was by Jeff Jones, who showed me the painting before I'd finished the book. The protagonist is holding a knife and defending the girl. So I wrote that into the book as a scene. But the art director decided to "improve" the cover and had the knife repainted (crudely) as a sword, and had shackles added to the girl, twisting her body in an anatomically absurd position. Pissed Jeff off no end, and me too.

Per Ted, Jeff is working on rewriting the rules of conduct for cover artists (keeping original paintings, selling only one-time repro rights). If successful, it will be a boon for all artists.

Anyway, as for the story…

Bob Tanner is wakened inside some sort of vault, naked, amnesiac. The robot brain inside exhorts him to explore the outside world, to spend a year amongst the humans, then report back with what he finds.

It turns out that civilization is long passed. He first arrives at the ruins of New York, the outskirts of which are inhabited by the most primitive of survivors, generations removed from the civilization Tanner only remembers in fragments. He is captured but escapes, taking with him the young Rifka, a captive member of the tribe.

Thus begins a series of adventures including a tangle with a bear, a run-in with a more advanced town with a mayor who doesn't let newcomers leave, a widespread constellation of farming communities at a 19th Century level of technology, and even a super-advanced enclave run by a group of individuals who were once the underdogs of society.

Through it all, Tanner becomes increasingly aware of his non-human nature—his metal bones, his ability to breathe fire, the hyperspeed he is capable of in brief spurts. And, at last, he discovers who he really is and decides what destiny he will forge for himself.

As is typical for Ted's books, I tore through this novel in short order. The man can't write a dull sentence even with a gun to his head. He takes the most cliché of settings and turns it into something fresh, certainly a damnsight better than Zelazny's recent stab at postapocalypse with Damnation Alley.

This may sound silly, but what I really liked about the book is that it's a romance. And not a "superman claims grateful damsel as prize" romance, but a believable progression of a relationship. Rifka is a well-realized character, one imbued with passion and an independent nature and set of priorities. It's not surprising that Ted draws her with such care—she is named after his wife, Robin Postal (Rifka means Robin in Yiddish). But, in general, the author is good with his female characters, surprising not just for the genre, but for the pulpy subgenre and venue.

I also really appreciate that one gets a pretty full picture of Bob Tanner even without having read the first book (in fact, I haven't, though it's on my shelf—it's really tough to find the time to read everything; even stuff you know is good). Honestly, the only real demerit to the book is its structure, really a series of vignettes. In that way, it is reminiscent of Omha Abides, C.C. MacApp's recent After-The-Apocalypse novel. Sure, White writes it better than most anyone else, but it still suffers from the disjointed, episodic nature of it.

Still, 4.5 stars, and I'm sure it'll make the Galactic Stars or at least get honorable mention this year.

by Jason Sacks

Star Well, by Alexei Panshin

I have a new favorite science fiction writer whose work I’m going to track. His name is Alexei Panshin and he’s had a terrific 1968.

Several months ago I reviewed Panshin’s novel Rite of Passage and found it intriguing, with great atmospherics, complex characters and a clever attitude which seemed to tell the story in multiple dimensions. Panshin told his story with a slightly ironic reserve to it, an approach which gave a detached commentary on the events, as if the narrator of the tale was someone looking back fondly at the events which shaped her.

That element is on display again in his newest novel, Star Well, but this time that ironic detached commentary reads like wry takes on the world readers are experiencing in the novel. For instance:

The apparently frightening and hopeless situation may turn out to have a candy-cream interior. That has been the main premise of the happy ending since the return of Ulysses.

Or he brings in a cute, clever meta-commentary about plot elements which gives the reader an aha! kind of feeling:

When managers of illicit traffic meet, their biggest plaint is the employment problem. In a word, henchmen. There are all too few young crooks willing to take training service under older and more accomplished men.

… a commentary which then goes into a detailed explanation of why it’s so dang hard to get good help these days, especially in a star base many light years away from anything important.

In short, these excerpts read like a bit of postmodern commentary on the space opera of Robert Heinlein. And since Panshin has written a monograph about Heinlein (Heinlein in Dimension, available through your local library, I’m sure), that reference has to be intentional.

The lead character here is one Anthony Villiers, a kind of lazy trust fund baby who’s spending his life just wandering the Nashurite Empire, occasionally drifting when he has cash, occasionally grifting when he doesn’t have cash. He’s aristocratic and hates getting his hands dirty, but he also has a gentlemanly aspect about him which makes Villiers feel charming and kind.

Villiers finds himself at the Star Well, a space port/gambling hall/shopping stopover which has been drilled into an asteroid in an area of space in which “the stars don’t grow”; in other words, a simple stopover for travelers who need a warm bed and maybe a touch of the illicit while on their way to their final destination. As such, it’s a perfect place for illegal smuggling and inept, corrupt bureaucrats who are striving to improve their social position or at least their bank accounts.

As you might guess, Villiers can’t help but get involved in the events at the Star Well, becoming quite the reluctant hero as he finds himself in conflict with Godwin, a man of low birth who yearns to be aristocratic, and Godwin’s boss Hisan Bashir Shirabi, a man with a massive inferiority complex who yearns to be like Villiers. Our protagonist also becomes unexpectedly close friends with the fifteen-year-old Louisa Parini, who traveled to Star Well en route to a stuffy finishing school but who craves adventure.

This is all so lightweight and enjoyable, and this whole charming souffle of a novel comes in at a mere 154 very quick pages – just like a Heinlein juvenile. And just like one of the juvies, there’s plenty of hints we’ll see more of Anthony Villiers in the future as he continues his peripatetic wanderings. I hope to spend many years following our besotted aristocrat as he wanders through the Nashurite Empire.

3.5 stars

As John Boston noted in his review of Heinlein in Dimension … Heinlein blew his cork over that book.

Interesting account of a Panshin – Heinlein confrontation here:

https://groups.google.com/g/rec.arts.sf.written/c/u-33vcVJKdk?pli=1

"Keep Calm and Carry On"

That's an obscure reference. Near as I can tell that's the slogan from a poster that the UK planned to distribute during the War, but which Her Majesty's government never actually used (I'll bet there are some copies still lying around in government warehouses though – if someone from the next generation finds them, it will no doubt be puzzling for them).

You know I could swear I saw some of them around when I was younger but maybe it is a false memory.

I was reminded of it when I recently read a copy of Walt Reed's Illustrator in America, and it has an drawing from Life Magazine of a London Underground Station with one of these posters up:

https://archive.org/details/illustratoriname0000reed_z1w0/page/132/mode/2up?view=theater