by Victoria Silverwolf

What's The Big Idea?

Science fiction writers often take novellas that have appeared in magazines and turn them into novels, to be published as books. Sometimes this doesn't require any expansion of the original at all, particularly if it's half of an Ace Double.

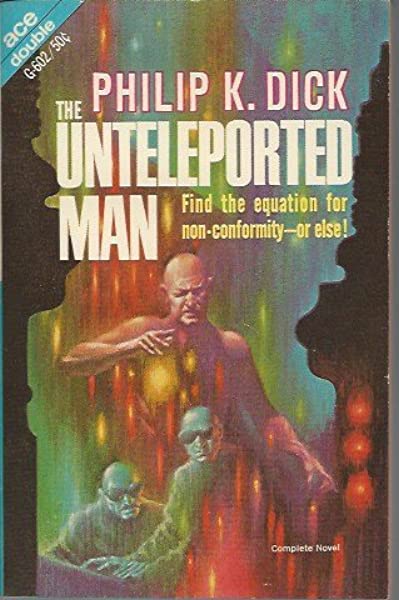

Case in point, as Rod Serling might say, is The Unteleported Man by Philip K. Dick, which appeared in the December 1964 issue of Fantastic.

Cover art by Lloyd Birmingham. It's not really a complete short novel, but you'll rarely see the word novella in a magazine.

It showed up as half of Ace Double G-602 without any changes. (In case you're wondering, the other half was something called The Mind Monsters by somebody named Howard L. Cory.)

Cover art by Kelly Freas. It's still not a complete novel.

On the other hand, an author can make use of the big (and profitable) idea of reusing old material by adding new stuff to it. One example is The Whole Man by John Brunner. The first half is original, while the second half makes use of two previously published novellas.

The cover art is anonymous, and deserves to be so, in my opinion.

With that background in mind, let's take a look at a recent example of stretching a novella into a novel.

What's The Story?

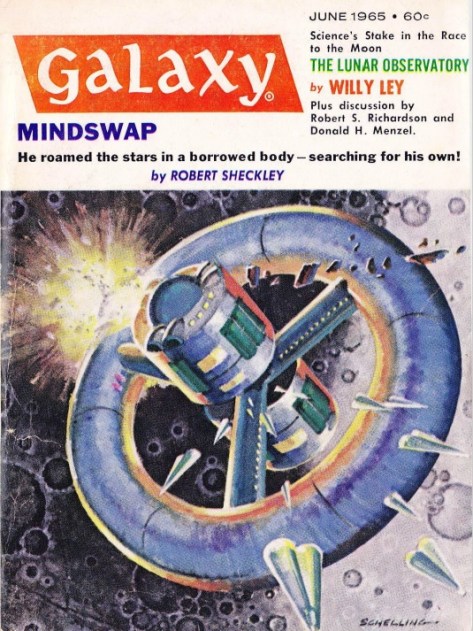

I'll start with the magazine version of Mindswap, Robert Sheckley's comic tale of a fellow whose consciousness goes bouncing around the universe from body to body. It appeared in the June 1965 issue of Galaxy.

Cover art by George Schelling. The table of contents calls Mindswap a, you guessed it, complete short novel.

Our Gracious Host didn't care for it, awarding it only two stars. That's a matter of taste of course, as I'll discuss later. For now, let me outline the plot, so we can compare it with the novel.

Marvin Flynn is a fellow who wants to travel to other planets, but who can't afford the extremely high price of space travel. Fortunately, the process of switching bodies with somebody, even over interstellar distances, is a lot cheaper. (Maybe not the most plausible premise in the world, but let's go with it.)

He answers an ad from a Martian who wants to mindswap with an Earthling. The bad news is that the Martian is a crook, who has already sold his body to a previous customer, and who runs off with Marvin's body. Marvin has to mindswap again, in order to avoid dying when he gets kicked out of the criminal's body.

Having no other choice, he winds up in an alien body, working as an egg catcher. These aren't ordinary eggs. They talk, for one thing. In addition to that, the dinosaur-like beings who produce the eggs hunt down those hunting the eggs. Facing a very unpleasant demise in the jaws of one of these creatures, Marvin mindswaps once more.

This time he's in the body of an insectoid alien, and he has a ticking ring in his nose that might be a bomb, ready to go off in the near future.

Things are already complicated enough, but it gets a lot weirder. You see, the act of mindswapping tends to cause the swapper to perceive reality in odd ways. The story turns into a parody of cowboy fiction when Marvin hallucinates that he's in the Old West.

Without going into too much detail about a complex plot, let me just say that Marvin falls in love, loses the woman he adores, searches for her with the help of a peculiar companion, confronts the villain who stole his body, and winds up back on Earth. There's a twist at the end.

What's New?

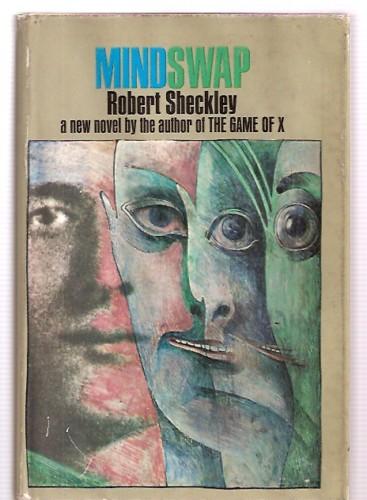

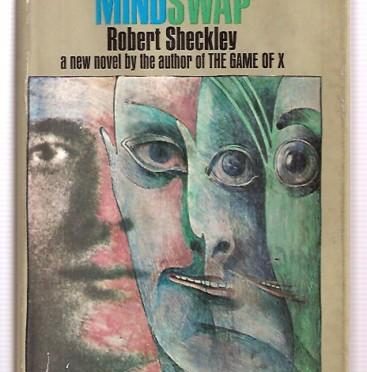

Mindswap just came out as a hardcover novel from Delacorte Press. Is it worth paying the three dollars and ninety-five cents they're asking at the bookstore? Let's find out. (Or you could just wait for the paperback edition, which should cost just about as much as the magazine did.)

Cover art by James McMullan. By the way, The Game of X isn't science fiction, but a comic spy novel.

At first, there seems to be very little difference between the novella and the novel. That changes at Chapter 24 (out of 33) or, if you prefer, on page 151 (out of 216.) Either way, that means that not quite one-third of the book is new.

In the short version, Marvin runs into the Martian crook a lot quicker. In the long version, there's a major section of the book where he gets involved in a swashbuckling adventure. Reality has completely broken down at this point, so you'll just have to accept the fact that he starts acting and talking like somebody in an Errol Flynn movie. After that, we get the same twist ending as in the magazine.

What's So Funny?

Appreciation of comedy is very much an individual thing; more so, I think, than appreciation of any other form of art. Maybe I like the Marx Brothers and you like the Three Stooges. Each of us would have a difficult time convincing the other of the superiority of our differing preferences. Without arguing for the merits of Sheckley's work, allow me to discuss the various forms of humor he employs.

Slapstick

Maybe we can define this as amusement at another person's woes, as long as they're ludicrous. When Marvin is about to get his head bitten off by a dinosaur, or when he expects to have the bomb in his nose explode, we can laugh at his anxiety.

Parody

I've already mentioned the spoofs of Western and swashbuckling fiction. There's also a section where, for ridiculous reasons, characters start speaking in pseudo-Shakespearean verse. The novel as a whole seems to be a parody of science fiction itself.

Wordplay

This occurs all through the book. Right at the start we hear Marvin and his buddy talk in futuristic slang that borrows from other languages. (Might Sheckley be making fun of the Anthony Burgess novel A Clockwork Orange?)

The author delights in silly names, of which there are dozens, if not hundreds, scattered throughout the novel. Marvin's companion during his search for his lost love alternates speaking in a thick, stereotypical Mexican accent and formal English. During the swashbuckling section, everybody talks in a highfalutin' fashion that you'd only hear in a romantic novel or a Hollywood movie.

Illogic

Reminiscent of Lewis Carroll's Mad Hatter, Sheckley's characters often reason in ways that might seem superficially logical, but which expose their inside-out and upside-down thinking.

The Martian detective searching for the criminal (I didn't mention him, did I?) figures that probability is on his side; he's failed to solve 158 cases, so he's bound to solve this one.

The hermit who mindswaps Marvin from the egg hunter's body into the insectoid body (I didn't mention him either, did I?) speaks in verse because he thinks it protects him from the dinosaurs. His proof? That he hasn't been killed yet.

The pseudo-Mexican helping Marvin in his search (I did mention him, didn't I?) has an unusual theory of searching; just go somewhere and wait, so that the searcher becomes the searchee.

Overall, I have to say that the book amused me. It doesn't have quite the same satiric bite as some other Sheckley works, but it made me smile all the way through.

Three and one-half stars.

What's Next?

I'm sure that other writers will continue to turn stories into novels. (The series of linked stories by Robert Silverberg that started with Blue Fire and which recently ended, or so it seems, with Open the Sky cries out to be a novel.)

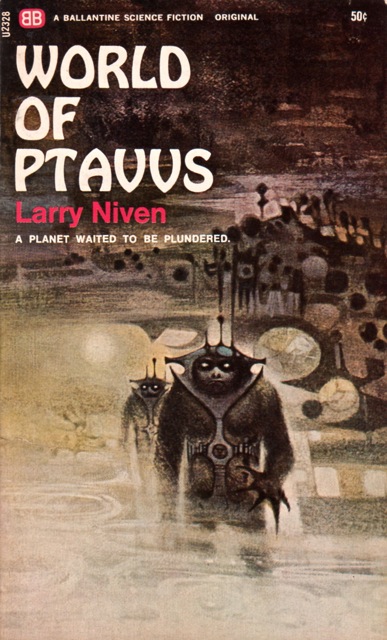

My sources in the publishing industry tell me that Larry Niven's impressive novella World of Ptavvs has been expanded into a novel, and will appear in a few months. Here's a sneak preview.

Cover art by Norman Adams

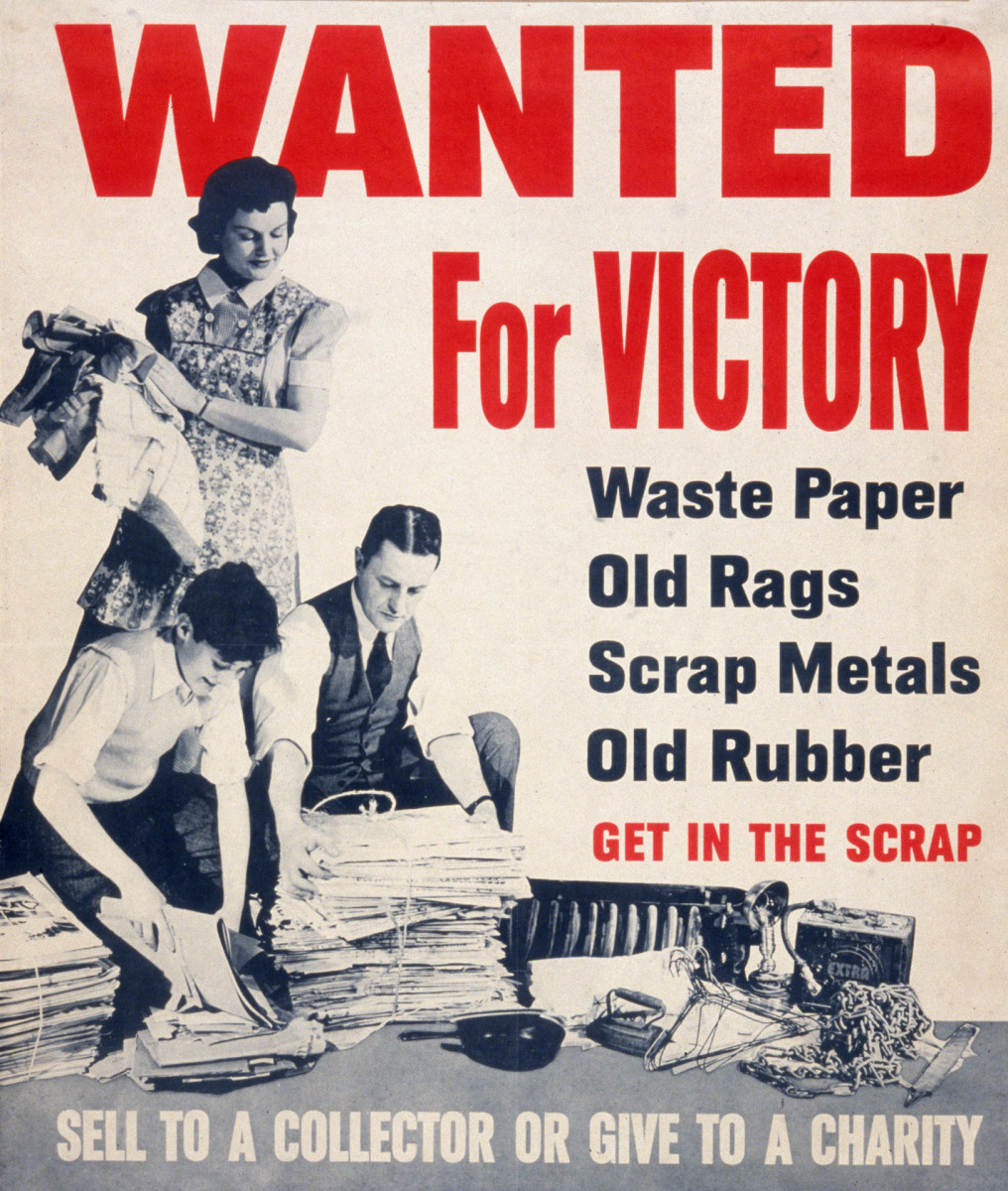

And just to prove that authors aren't the only ones to reuse old material, just take a look at this book from 1963.

Look familiar?

All of us should heed the example of writers, artists, and publishers, and reuse whatever we can. It's the patriotic thing to do.

Junior looks like he might be searching through old science fiction magazines.

If you want to hear some great current music, then tune in to KGJ, our radio station! We never reuse the old songs!

Do we know that MINDSWAP was expanded from novella to novel, as opposed to being pared down from novel to novella? As the center of gravity of SF publication shifts from magazines to books, I gather it is now increasingly common to sell longer works for book publication and then seek magazine publication pending appearance of the book, making what adjustments are necessary to fit the magazine's space and other requirements.

I found Mindswap delightfully entertaining. And I can predict I'll reread it a few more times in the future.

The key to enjoying Sheckley's longer works is don't consume them all at once. A little Sheckley goes a long way. And it's easy to divvy Sheckley's novels into bite-size pieces since he naturally plots his longer works as a series of standalone sketches.

Depending on my mood, those sketches can flop or dazzle. And I can tell you from experience that the Theory of Searches actually works.

Looking forward to the World of Ptavvs expansion.

Sheckley's MINDSWAP and DIMENSION OF MIRACLES are two of the funniest and most inventive satires I have ever had the pleasure to read.

"The Journey of Joenes" AKA "Journey Beyond Tomorrow" is in the same category as well. Good stuff.

Thanks for the explanation about the difference between the magazine and book versions. Very useful. If Pohl got rid of the medieval adventure section (my memory is hazy on the details) then that strikes me as a judicious piece of editing.

I believe at least three of Wilson Tucker's science fiction novels were revised by the author and republished. A prime example is his Ice and Iron (hardcover) and Ice & Iron (paperback). Frank M. Robinson did the same with The Power after more than 40 years.