by Cora Buhlert

A Cold Night in Munich

In my last article, I wrote that a feeling of hope and optimism was permeating West Germany ever since the general election last fall. Sadly, on February 13, 1970, those good vibrations were disrupted by a reminder of the darkest time of German history.

It was a cold Friday night in the Glockenbach neighbourhood of Munich. The shops on Reichenbachstraße had already closed for the night and in the Victorian apartment buildings lining the street, people were enjoying the start of the weekend.

On of the buildings along Reichenbachstraße is the Munich synagogue, built in 1931. It was the only synagogue in Munich to survive the Reichskristallnacht on November 9, 1938, because the Munich fire brigade stopped the Nazi mob from setting fire to the building, insisting that a fire would spread out of control and burn down the entire densely populated street.

After World War II, the synagogue reopened and now serves as the main synagogue for the Jewish population of Munich. The Jewish congregation of Munich also purchased an adjacent Victorian apartment building to serve as a community centre, library, restaurant, kindergarten and as a home for elderly members of the congregation and students.

Shortly before nine PM, an unknown person or persons entered the community centre, took the elevator to the top floor and spread gasoline in the wooden stairwell on their way down. Then, they struck a match, lit the gasoline and fled. The resulting fire spread rapidly through the old building.

At the time of the arson attack, fifty people were inside the community centre, celebrating the sabbath. Forty-three of them were rescued by neighbours and the Munich fire brigade. However, the fire in the stairwell had cut off access to the upper floors of the building, trapping several resident in their rooms.

Twenty-one-year-old medical student Sara Elassari, who lived on the top floor, managed to escape through the window and scramble down a drain pipe, from where she was rescued by the fire brigade. Seventy-one-year-old Meir Max Blum, who had returned from the US to his city of birth only the year before, jumped from a window and succumbed to his injuries. Six other residents aged between fifty-nine and seventy-one were found dead in their rooms. All seven victims had survived the Holocaust – some in hiding, some in exile, some imprisoned in concentration camps – only to be murdered in their homes in supposedly peaceful West Germany.

Too Many Suspects

As of this writing, we do not know who is responsible for this terrible tragedy. The Munich police are following various leads. The obvious suspects would be the far right, since West Germany has no shortage of old and new Nazis. However, there is also evidence pointing at an eighteen-year-old far left radical with a history of arson, because Anti-Semitism does not thrive only among the right.

Finally, the arson attack might also be connected to the Middle East conflict, especially since a Palestinian terrorist group had tried to hijack an El Al plane during a stopover at Munich-Riem airport only three days before. The hijack attempt failed, but one passenger, thirty-two-year-old German-Israeli businessman Arie Katzenstein, was killed and ten other people were injured, some of them critically. On February 17, another hijack attempt was foiled, also at Munich-Riem airport but thankfully without casualties. Were the same terrorists also responsible for the arson attack? So far, we don't know.

However, the sad truth remains that twenty-five years after the end of the Third Reich, eight Jewish people (the seven victims of the arson attack as well as the victim of the airport attack) were murdered and several others injured in the heart of Munich. The old venom of Anti-Semitism is back, if it ever left in the first place.

Nuclear War as Comedy

When the world outside becomes too terrible to bear, the cinema offers a respite for an hour or two. And so I headed out to see a movie that debuted at last year's Berlin Film Festival, but is only now reaching West German cinemas. And since the movie was billed as a comedy, it would seem to guarantee a good time.

The movie in question is The Bed Sitting Room, the latest film by maverick director Richard Lester. Best known for helming the two Beatles movies A Hard Day's Night and Help!, Lester has also made a name for himself with anarchic comedies such as The Knack …and How to Get It or A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. However, it's How I Won the War, an anti-war black comedy starring John Lennon, which piqued my interest in Lester's work, because parts of it were filmed around the corner from where I live with tenth-graders of Achim high school serving as extras and the Weser bridge in Achim-Uesen standing in for the Rhine bridge in Remagen, though no one who knows the Uesen bridge was even remotely fooled.

Having enjoyed Lester's previous movies, I was eager to see his latest. Of course, the title The Bed Sitting Room sounds like one of those dreary kitchen sink dramas that are popular with socially conscious British directors. But this is a Richard Lester film and Lester doesn't do dreary.

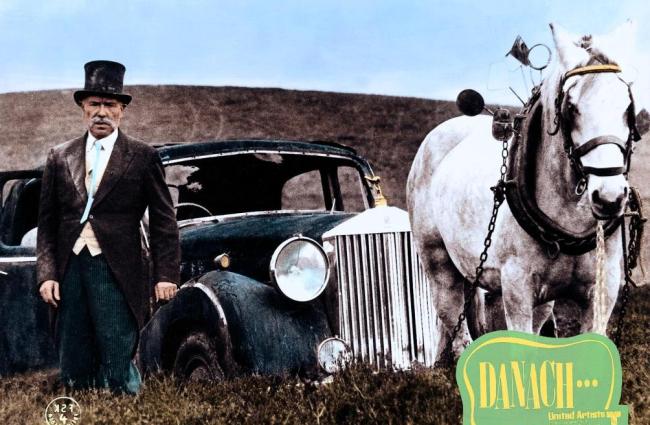

In many ways, the German title Danach (After) is more fitting, because The Bed Sitting Room is a movie about the aftermath of a nuclear war that lasted all of two minutes and twenty-eight seconds, including the time taken to sign the peace treaty. In a completely devastated Britain, a handful of survivors try to carry on a semblance of normality, while dealing with radiation, mutations, disease and each other. Sounds like a downer, right?

Keep Calm and Carry On

However, this is a Richard Lester film and so instead of a serious movie about the aftermath of a nuclear war, we get a black comedy. The royal family was incinerated along with forty million other Britons, so Britain is now ruled by Mrs. Ethel Shroake of 393A High Street, Leytonstone, former charwoman to Queen Elizabeth II and closest in line of succession to the throne. She certainly looks regal mounted on a horse beneath an arc of triumph fashioned from old refrigerators.

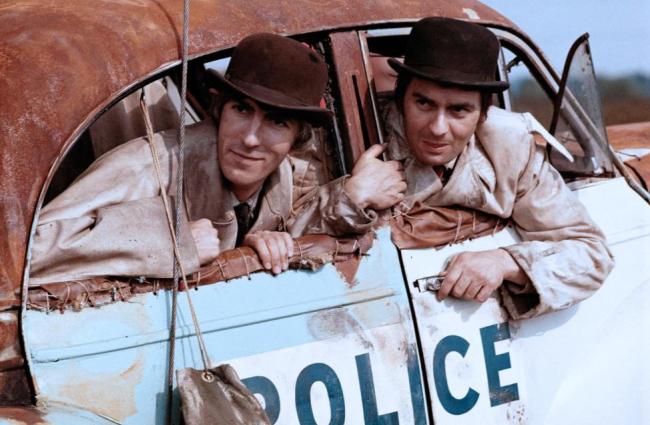

Other British institutions carry on as well. The BBC is reduced to a single newsreader in a tattered suit who dashes from survivor to survivor to deliver the news sitting inside a broken television set. The National Health Service has been reduced to comedian Marty Feldman clad in a nurse uniform. The police consists of two officers patrolling what remains of Britain in the wreck of a Morris Minor suspended from a hot air balloon. St. Paul's Cathedral is mostly submerged and the vicar is performing services underwater.

Then there is Lord Fortnum of Alamein (Ralph Richardson) who has a problem. He is mutating due to radiation and slowly turning into a bed setting room. This is quite upsetting for him, because a bed sitting room is not at all a suitable form for a Lord. Nor is he the only one thus afflicted. In the course of the movie, a woman turns into a cupboard and her husband transforms into a parrot. The cupboard furnishes the bed sitting room, somewhat alleviating the post-war housing crisis, while the parrot feeds the survivors.

In addition to Lord Fortnum of Alamein, the closest thing to a protagonist this film has is Penelope (Rita Tushingham) who survived the war on the London Underground together with her parents. The family has been riding the Circle Line for the three years and subsist on raiding the chocolate vending machines on the station platforms. The London Underground surviving a nuclear war is one of the more believable things happening in this film. Though the Circle Line is a sub-surface line and would probably be destroyed, whereas deep level lines such as the Picadilly, Northern, Central and Victoria lines have a higher chance of survival.

Penelope's parents are worried about her, because she doesn't get out enough, tends to wander off and is also gaining weight. To the viewer, it's bleedingly obvious that Penelope is pregnant, though her parents are quite oblivious – at least until Penelope is late to return from one of her occasional walks. So her father goes in search of her and finds her in a compromising position on the floor of a tube car with a young man named Alan. After some misgivings, Penelope's parents accept Alan and he joins the family as they finally leave the tube to go in search of medical attention for the pregnant Penelope.

In a highly memorable image, the tube escalator drops Penelope, her parents and Alan onto an enormous pile of broken dishes. Other memorable visuals include wrecked cars half buried in the remnants of a motorway and a man digging through an enormous pile of boots. Lester shot the movie in various landfills and garbage dumps, lending the surroundings a highly surreal quality.

Mutations and Marriages

Lord Fortnum finally does turn into a bed sitting room, though he insists that his "doctor" Captain Bules Martin (who is very much not a doctor and not much of a soldier either) put a sign in the window saying "No coloureds, no children and definitely no coloured children", because even as a bed sitting room, Lord Fortnum maintains his racism and class prejudice.

Meanwhile, Penelope's father sees a chance for political advancement – he wants to become prime minister – and arranges a marriage between Penelope and Captain Martin, neither of whom is at all interested in this arrangement, since Penelope is in love with Alan and Captain Martin more interested in his old friend Nigel than his new bride.

Things look grim, when Penelope's baby is born dead after seventeen months of pregnancy and the bed sitting room that used to be Lord Fortnum of Alamein is about to be knocked down. But the voice of God – and Lord Fortnum – intervenes in the nick of time. The police inspector – his sergeant has been transformed into a dog – informs the assembled population that scientists have developed a cure for the mutation problem via full body transplants and that it only took the entire population of South Wales to find it.

Penelope and Alan have another healthy baby and live happily ever after with the dog that used to be a police sergeant. Captain Martin and Nigel move into the bed sitting and live happily ever after as well. It all ends with a heartfelt intonation of "God Save Mrs. Ethel Shroake."

Nuclear War is a Laugh

The Bed Sitting Room is an utterly hilarious movie. There were many moments where I came close to rolling on the floor with laughter. On the other hand, it is also a deeply depressing movie, because it shows the survivors of a nuclear war trying to carry on and maintain a semblance normalcy under conditions that are anything but.

The Bed Sitting Room is to Peter Watkins' The War Game as Dr. Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is to Fail Safe. Both tackle the same subject, nuclear war and its aftermath, but one treats it as a tragedy, the other as an extremely bleak tragedy. The Bed Sitting Room will make you laugh, but the laughter will also stick in your throat.

Five stars and God Save Mrs. Ethel Shroake of 393A High Street, Leytonstone.

And now I hand over to my esteemed colleague Fiona Moore who also chanced to watch The Bed Sitting Room recently and offers her take below.

by Fiona Moore

Poster for The Bed Sitting room

“We’ve got to keep going.” “Why?” “Because we’re British.”

Last year’s movie adaptation of Spike Milligan and John Antrobus’ stage play, The Bed Sitting Room, directed by Richard Lester, has finally been released to critical acclaim in this country. A surrealist, absurdist comedy set in a near-future Britain devastated by a nuclear war, it’s being cited as a comedically nightmarish take on the anti-war genre, The War Game by way of Monty Python, or perhaps a cinematic expansion of Philip K Dick’s tragicomic story “The Days of Perky Pat”.

I have a slightly different take on it, and would argue that its postwar setting is simply a frame for a skewering of late twentieth century British society.

We have a middle-class nuclear (see what I did there) family straight out of a sitcom, consisting of Father (Arthur Lowe), Mother (Mona Washbourne), Penelope (Rita Tushingham) and her lover Alan (Richard Warwick), who start the movie literally living on the Tube (as many Londoners feel we do in a more metaphorical sense). No one appears to be driving the train, but it goes along anyway. The family’s petty concerns about things like whether or not Alan is suitable for Penelope, having the right train tickets, and whether or not they look like vagrants are more central to their lives than the fact that they emerge from the Underground into a devastated wasteland full of crockery and cars.

Life in a desert of consumer goods

Life in a desert of consumer goods

We have a member of the aristocracy, Lord Fortnum, who is physically turning into a bed-sitting room and is anxious that he should be in a good neighbourhood (“put a sign in my window—no coloureds!” he shouts upon learning that he is in fact in Paddington). We have a blatantly unhinged nurse named National Health Service (Marty Feldman), who insists that Mona Washbourne is dead because her death certificate has been issued; we have another confused individual named The Army (Ronald Fraser) and another called The BBC (Frank Thornton, who wanders the wilderness giving news bulletins). When Penelope, having been pregnant for eighteen months, gives birth, National Health Service tries to keep the child in the womb instead, as there’s no point in coming out.

The BBC doing his job

The BBC doing his job

The general impression is of a society that is degenerating into chaos, ruled by people who literally are property, and whose once-celebrated institutions have fallen into absurd bureaucracy. Throughout it, people keep to social rituals even though there is plainly no use for these any more, singing “God Save Mrs Ethel Shroake” (the closest surviving person to the throne), and one man (Henry Woolf) desperately riding an exercise bike in order to keep a lightbulb burning, saying that “electricity is the lifeblood of civilisation”. As society breaks down, people become more selfish and cruel. Father turns into a parrot and is eaten by the people in the bedsitter; Penelope’s baby dies and her bedsit-mates are oblivious to her grief; everyone avoids saying the word “bomb” and, when they do, it seemingly causes a wrecking ball to come out of the wilderness and attack the bedsitting room. The story is plotless, episodic and absurd, making as little sense as anything does these days.

While the ending is optimistic, it’s one which suggests Britian has to go through hell in order to achieve a new equilibrium, and the final scene has Penelope and Alan in a field of poppies, making anyone who’s seen Oh What a Lovely War wonder if they haven’t, in fact, died.

I feel like a stuck record saying this but, as with just about all British comedy (and indeed New Wave SF) at the moment, the main criticism I have is that this is largely an all-male revue. The only female characters are Penelope and Mother, who are walking ciphers whose lives are controlled by the men around them. No satire of British society can really be complete, in my opinion, unless it addresses the chauvinism that pervades our political, social and economic systems.

Nonetheless, as a scathing movie that contains much to offend the Establishment, it’s very much worth a watch and is likely to become a firm favourite of the student film societies and the local cinema’s more arty repertory evenings. Four stars.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

This is a strange one that has stayed in my memory. Thanks for the reviews!

Thank you both for your reviews.

I think the comparison to The War Game is apt in another way, in that it is built around a series of stark images that stick in the mind. Even though The Bed Sitting Room has some memorable dialogue, I almost think of it as a gallery of experimental artworks you would see in a trendy gallery in West London.

The point Fiona makes about the current sense in British media is also apt. I think it has come from the fact that the UK is no longer either the biggest economy in Europe nor a world power and has to now compete with many other countries in production of goods. Unfortunately, rather than simply seeing them as symptoms of modernity all countries are facing, many writers and politicians seem to have become apocalyptic about it. Even though there are fewer days lost to strikes than in the US, the Unions must be secret puppeteers controlling the nation. There has been a slight increase in violent crime, the country is in lawless anarchy. A minor US official makes some disparaging remarks about Wilson, clearly an American backef coup is imminent.

I actually enjoy this type of science fiction exploring these themes, but it seems to have almost become a core part of the British Psyche today, that total societal collapse is only a day away.