by Gideon Marcus

The other shoe dropped on February 17: Star Trek is officially canceled. Moreover, ABC won't pick it up for its "Second Season" in January. Fan efforts are being directed at CBS, but I can't say the prospects are promising.

One has to wonder if the decision was made due to the spate of lousy episodes that have plagued the second half of the Third Season. On the other hand, the decision was probably made based on the reaction to the first half of the season, which was actually quite good, so maybe Trek was always destined for the block.

This makes the latest episode, what appears to be the penultimate (if, indeed, they even air the last episode sometime in May after eight weeks of reruns and substitutions), particularly bittersweet. "All Our Yesterdays" is possibly Trek's finest hour, even as the clock ticks the show's last minutes.

That the show is so good comes as no surprise; writer Jean Lisette Aroeste wrote the sublime "Is There in Truth No Beauty", and director Marvin Chomsky ran the excellent "Day of the Dove". It is also an unique episode in many ways, from the profusion of excellent sets, to the complete absence of the Enterprise from the show (a phenomenon I cannot recall occurring in any prior episode).

For those who missed it, Kirk, Spock, and McCoy beam down to the planet of Sarpedon, a civilized world doomed to be destroyed when its star, Beta Niobe, goes nova—in just a handful of hours. I guess they're there to pick up refugees (if so, there won't be very many…)

The Big Three find themselves in what looks like a post office or safety deposit box annex attended by an elderly Mr. Atoz. This fellow, assisted by several kindly replicas, is a "librarian" who has used his "Atavachron" (a great name for a time machine) to send all of the citizens of Sarpedon into the past, where they will be safe from the stellar explosion. Mr. Atoz assumes the three officers are Sarpedonites who are late to the party, and he gives them run of the archive to find eras to jaunt to.

"You've run up some considerable overdue book fines, young man!"

Well, through misadventure, Kirk ends up in Cromwellian England, where he is locked up under accusation of witchcraft, and McCoy and Spock end up in the planet's last Ice Age, risking frostbite and worse. Apparently, Sarpedon's past is identical to that of Earth, which would be egregious if we hadn't seen similar phenomena in "Miri" and "Bread and Circuses". Indeed, this is actually a welcome data point rather than risible.

"You're under arrest, guv'nor…for overdue book fines!"

"It's colder than a witch's left…" "Agreed, Doctor."

Luckily for Kirk, his judge is one of the refugees from the future, who helps him find the portal back to the library. Luckily for the other two, a lovely woman named Zarabeth, exiled from a time prior to the Enterprise's era, rescues them and gives them refuge in her cave. She quickly falls for Spock (who wouldn't?) and the half-Vulcan finds himself reverting to savagery as a result of his psychic bond with primordial Vulcans of five thousand years ago. Spock peeves at McCoy, moons at Zarabeth, and acts the least Spocklike we've seen him since "This Side of Paradise" in a very honest and affecting way.

Bones convinces Spock to go back to where they arrived in the Ice Age so as to find their way back to the library, which they manage with the help of Kirk. Returned to his time, Spock becomes himself again, but not without a touch of subdued regret at the loss of yet another opportunity at love.

The pacing for this episode is leisurely but consistent, really letting us soak in the environs, the characters, their emotions. The Act-end cliffhangers are unusual and sometimes not even danger points. All of the cast turn in masterful performances, and the guests do as well—standouts include Mr. Atoz (the actor last seen in "Bread and Circuses") and the magistrate who saves Kirk. Mariette Hartley (Zarabeth) is fine, and there is no question that she is lovely, but it's the pickpocket who Kirk rescues in his era, with her period speech and game manner, who is truly memorable. The optical effects are stunning, particularly the Atavachron portal effect.

"Just give the book back. No one will press charges."

Though something of a cul de sac in terms of development of the setting (time travel on Sarpedon only goes to Sarpedon, and the system blows itself up at the end of the episode), it is the opposite of a bottle show. There is absolutely nothing wrong with this episode, and so much that is right.

Five stars

Historically Inaccurate

by Erica Frank

In this episode, we see a mirror-image of the usual dynamic between Spock and Doctor McCoy. The doctor is the rational one, driven to find a solution that lets them get back to the Enterprise—while Spock is distracted by strange circumstances and a pretty lady, and he risks isolating them both because of his emotions.

He attacked McCoy over the epithet "pointy-eared Vulcan"… and although the insult was clear in McCoy's voice, it's also a simple fact: Spock is a Vulcan and his ears are pointy. McCoy has said more directly insulting things to him in the past, but this was apparently his breaking point.

You'd think if he wanted McCoy to shut up, he'd use the Vulcan neck pinch on him. Instead, he grabs him by the throat and brings him in close.

We are supposed to believe that tensions have come to a head because Spock is stuck in the past and atavistic patterns are controlling his behavior. That Spock reverts to savagery because the Vulcans of several thousand years ago were warlike barbarians who ate "animal flesh" and fought for dominance over petty insults.

The problem with that is…

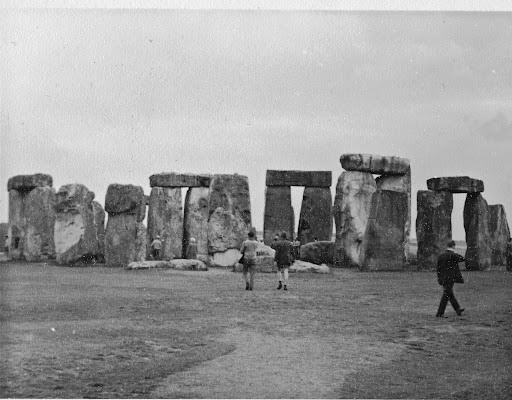

Five thousand years ago on Earth, the Aegean Bronze Age was starting. Imhotep built the Step Pyramid of Djoser; around the same time, Stonehenge was built. Those were ancient human cultures, but they were not so alien from modern humans that a person transported to that time would find their entire nature changed. A modern human thrown back to that time — even with their cell structure and brain patterns adjusted to fit in — would act much like humans do today.

Our records show that human activities and motivations have been very similar throughout history, even as our technology and religions have changed. People complained about politicians, bemoaned their rebellious teenagers, and mourned the passing of beloved pets. Some fought over minor differences and more sensible people denounced those who could not get along with their neighbors. Some were involved in huge, elaborate projects that would not see completion in their lifetimes, and yet they found reason to participate and build on the work of those who had gone before.

Visitors at Stonehenge, perhaps considering what life might have been like 5,000 years ago on Earth.

"Stonehenge 1960s" photo by Annabel M, CC-BY 2.0

Are we to believe that Vulcans were violent barbarians much more recently than humans? That while humans were developing cuneiform and hieroglyphs, establishing the basics of accounting and medical texts, Vulcans were irrational and vicious—but have since surpassed humans in technology and developed powerful psychic abilities?

Something about this doesn't add up. I can more easily believe that Spock, badly disoriented by the trip through time and deeply worried about his friend's survival, latched onto the first viable way to cope: Accept that they are stuck here and focus on surviving in their new home.

Of course, this is only plausible if one believes that Spock would give up his friendship with Kirk for a life with McCoy and a woman he met an hour ago. That possibility raises even more questions.

Four stars. I can quibble over some of the "science," but the character dynamics were riveting.

Treasure from Trash

by Joe Reid

This week’s episode of Star Trek contained many interesting elements: a star about to go Nova, eliminating a solar system and the desperate race to find survivors. A man with duplicate copies of himself. A civilization with the power to travel in time. All interesting concepts that could fill volumes of science fiction. Sadly, these concepts were cheapened by the unnecessary common plot devices which ran rampant in this episode. From jumping to conclusions to failing to ask questions, there didn’t appear to be any characters in this episode unwilling to make critical mistakes that made situations worse than they already were.

Let’s start our examination on an individual level with Kirk and Atoz. Kirk and crew went to a doomed planet where everyone was gone, looking for people to save. Atoz, having saved everyone, was perplexed as to why these newcomers hadn’t escaped yet. This left us with a comedy of errors that shouldn’t have occurred. Had Kirk or Atoz not jumped to conclusions and taken a minute to fully introduce themselves and state their purposes, all parties would have been allowed to move on with their respective businesses without incident. Instead, we were forced to bear witness to two men fighting so hard to save each other they were willing to almost kill each other.

"Kirk, go to your room!"

The second cause of frustration in this episode revolved around the fact that questions were never asked during the times when people were the safest. Again, our two subjects are Atoz and Kirk, but mainly Kirk. Had Kirk asked before he leapt to aid the sound of a screaming woman, he might have saved himself some trouble. Even Spock and McCoy fell into the same situation, chasing after Kirk’s voice as he had the woman. Have none of them ever been taught that the time to ask questions is when you are still at the library, not after you’ve left? Eventually Kirk and crew were able to formulate questions after they found themselves in predicaments. They discovered the answers which led to their salvations. All completely avoidable.

At the end of the day, these mistakes lead to the exploration of fantastical places with many surprises. The journey to the frozen wastes, where Spock and McCoy find the lonely and beautiful prisoner, pushes Spock and McCoy to the brink both physically and emotionally. Kirk has to find unwilling allies in a strange past to save himself from his own prison, and after all that, has to fight to prevent re-imprisonment to save the lives of this crew. I found it amazing that this episode was able to push beyond the cheap narrative devices to deliver a worthy hour of TV. It ultimately rewarded the viewer’s patience for putting up with these forgivable follies to get to some good sci-fi at the end. All gripes aside, I enjoyed watching “All Our Yesterdays”.

Four stars.

I liked the episode well enough, and it's a decent note to go out on (if that's the case), but I don't think I rate it as highly as any of the reviewers. Spock's atavism is probably my biggest complaint, though Gideon's explanation for it seems reasonable. If Spock can sense the bewilderment and deaths of a spaceship-full of Vulcans, then a whole planet of illogical, squabbling Vulcans is bound to have an effect on him. Erica's counterargument, however, is equally sound.

I didn't care for either of guests in Kirk's part of the story. The magistrate came across to me as a cut-rate Charles Laughton. The woman cut-purse's accent was atrocious; half music hall Irish, half Dick van Dyke in Mary Poppins. Mariette Harley has been better in other things I've seen her in, though her performance was certainly enhanced by the handiwork of Bill Theiss.

Can we also mention the idiocy of entering a star system where the star is predicted to explode in a matter of hours? That doesn't seem to be the sort of thing you could predict with more precision than "soon" or "in the next few months." Better hope the error bars on that prediction are really, really small.

"Are we to believe that Vulcans were violent barbarians much more recently than humans? That while humans were developing cuneiform and hieroglyphs, establishing the basics of accounting and medical texts, Vulcans were irrational and vicious—but have since surpassed humans in technology and developed powerful psychic abilities?"

Hmm. How about this: Vulcan emotional control is a conscious choice; therefore, promoters of emotional control (from Surak on down to Sarek's generation) have always taught (and by now believe) propaganda that says for Vulcans the only alternative to logic and emotional control is a life that is nasty, brutish and short, even though this propaganda is historically inaccurate. And the stress of Spock's current situation, combined with his subconscious belief that he's back not just in (what would for humans be) a time of less advanced but still complex and cultured societies but in fact in a time of brute chaos, Spock's emotional control breaks, and he begins to act in the way he's always been (carefully) taught that lack of emotional control will lead to.

This also explains why Vulcans have an attitude about humans – humans don't have Vulcan levels of emotional control, but they aren't savages everywhere and all the time – thus humans are living threats to Vulcan pro-emotional control propaganda.

"That while humans were developing cuneiform and hieroglyphs, establishing the basics of accounting and medical texts, Vulcans were irrational and vicious—but have since surpassed humans in technology and developed powerful psychic abilities?"

Civilizations develop at different speeds. China was far in advance of Europe at around 1 AD, but they have lagged behind the West since around 1700.

Also, we have no idea what the relative technology level of the Vulcans is. We have seen no Vulcan space ships. We know they crew a starship…with an American name. Yes, they have psionic powers, but we do not know if those were developed after or before the Romulan/Vulcan split, nor when the split occurred.

"Vulcan, like Earth, had its aggressive colonising period. Savage, even by Earth standards."

That's all we know.

My field notes…

Wig Trek: yes, the magistrate

Cave Trek: yes

Fog Trek: snow fog

Doinnggg Trek: no

Love Trek: yes

Relevance Trek: gloriously no

If this is the last Star Trek teleplay, the series is going out with a very good one indeed, worthy of the first season. But it needed to be shown during the (often unsatisfactory) third season because the Ice Age change in Spock’s character and the crisis in the Spock-McCoy conflict would not have had the impacts that they do have, if the show had been aired earlier in the Star Trek’s run. (Surely, after this experience, we must assume that McCoy left off baiting Spock forever. If this is the final Star Trek teleplay, it is good to have that bit of formerly unfinished business cleared up.)

In my dour notes on “The Savage Curtain” I wrote that, this season, romance has been a recurrent plot element – or even plot filler. We had romances for Kirk, McCoy, Scotty, and Chekhov. I erroneously included Spock in the list, but, really, his flirtation with the woman in the suspended city (“Cloud Minders”) may be passed over in tactful silence and probably shouldn’t count as a romance. But here we had a genuine romantic element for Spock, and, as with the Spock romance plots in each of the previous seasons (“The Side of Paradise,” “Amok Time”), this one appears in a teleplay that is better than the series average.

Nimoy and Mariette Hartley conjure believable, affecting dramatic chemistry. I said (approximately) in one of my earlier field reports that, for me, the gold standard for this is the performance of Robert Culp and Salome Jens in the Outer Limits teleplay “Corpus Earthling.” That remains true, but this Star Trek isn’t put to shame if it’s placed next to that show.

After so much face-painting of woman guest stars, one is happy that this device for a producing token “alien” look was skipped in this show.

Good casting was also done for the cutpurse woman and the magistrate in Kirk’s adventure. She looks like she’s had a hard life, while he conveys both knowledge that Kirk needs and, especially, a life of fear in that time – though a long time after watching this one, we might wonder why he chose that time and place for refuge in the past. Maybe he was sent there against his will, like Zarabeth. But you can’t answer all the questions in 48 minutes or so.

This teleplay is much better written than what we have been seeing lately. There’s no obvious artificial gimmick added to try to juice up a lackluster story; the imminent nova doesn’t come across so much as an obvious gimmick as the legitimate reason for the Enterprise being in the area in the first place. And the script doesn’t feel padded.

In the last few seconds we see the planet vaporized by its sun’s nova. This image underscores the note of loss verbalized just before, when Spock tells McCoy that “she” is “dead and buried” long ago. And the Enterprise sails away. That is, we have a conclusion to this television series, if this is the end, that is very fine. It’s understated but moving, easily one of the most moving bits in the whole three-year series.

Now, if that’s the end of new Star Treks, a couple of thoughts.

First, it looks like Relevance Trek has come to its end without broadcasting a Women’s Liberation show. Star Trek as Relevance Trek did hippies-and-cult-leader (“The Way to Eden”), racial prejudice (“Let That Be Your Last Battlefield”), class exploitation (“The Cloud Minders”), Vietnam (in the guise of “A Private Little War”), American anxiety about Communist China (“The Omega Glory”), “overpopulation” (“The Mark of Gideon”), and perhaps others I’m not remembering. The topicality was obvious in each of these and none of them was much good.

With Relevance Trek, you get the feeling that the script writer is looking at you over the top of the puppet-box stage and silently asking, “Hey you, do you get the point?” or sitting at your side nudging you in the ribs and whispering the same question.

Other than Women’s Liberation and – if the network allowed it – illicit drug use – what would have been left for Relevance Trek? Sex education in the schools?

Second – I found myself thinking, “Suppose Star Trek had run for just one season of 25 shows.” What would be the Star Trek season if it included only the better shows, the shows that really counted in one way or another? Maybe they had a cool idea or a special suspensefulness or an outstanding visual appeal or especially let one or more of the actors show what they could do, or maybe the show was just especially exciting.

Me, I’d come back to a criterion that I mentioned in a recent dispatch. The justification of a genre or entertainment medium is that it can do well something worth doing that could not be done so well any other way.

“The City on the Edge of Forever,” naturally, comes to mind, with the issue of changing history or not, and the sense of wonder surrounding the main story. Worth doing, but not possible to do outside science fiction or science fantasy.

So, with this criterion in mind, we could rule out the teleplays that are basically routine capers adapted to Star Trek’s givens but that could with little change have been Man from UNCLE shows or the like. Which are the shows we think were especially good at realizing what a science fiction space travel adventure series could do and that could not be done so well by some other type of entertainment? What weight do you give to sense of wonder?

Everything else being equal, shows in which problems are solved by the exercise of characters’ specific traits and by applied science will rate higher than ones that use more adventitious elements. For an example of a show that failed: in the wretched “Plato’s Stepchildren,” the “godlike” folk owe their powers to a naturally growing substance of some kind – I forget the details, some kind of baloney. It’s bogus.

Another criterion for making a selection could recognize that Star Trek relied too often on certain plot devices, notably “godlike” aliens. Which is the best one(s), with (most, at least, of the) others being ones we could rule out? For example, who needs “Catspaw”? The only thing that schlocky show had going for it was the brief bit at the end when the real appearance of the aliens is revealed. Wow! But the rest was bunk.