by Fiona Moore

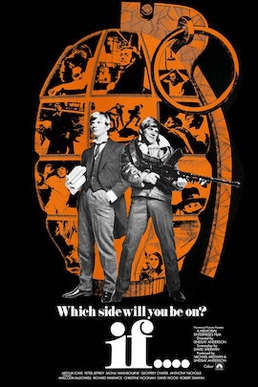

If…. is a movie which came out a couple of years ago, but is rapidly becoming a staple of the college film society scene here in the UK and overseas. It’s firmly within the satirical-surrealist tradition that characterises the likes of The Prisoner (with whom If… shares an editor, South African activist Ian Rakoff), Monty Python, and The Bed Sitting Room. The question is, how well does that stand up as time and cinematic fashion move on?

The story is set at a British all-male boarding school, where young men from the privileged classes learn the rigid, brutal, complex hierarchies and rules which will characterise their adult lives as well. Through the lens of a new arrival, we encounter a world where senior prefects enforce a rigid regime, obsessed with trivialities like hair length and permitted foods but enforcing this through corporal punishment; where younger students are forced to act as servants to their elders, with an implied sexual dimension to this servitude; where religion and the military bolster and reinforce the regime. However, the school also has its rebellious counterculture in the form of three young men, the “Crusaders”, led by Travis (played by newcomer Malcolm McDowell, whose performance here has reportedly led to Stanley Kubrick casting him in his forthcoming adaptation of A Clockwork Orange). their rebellion begins with minor acts of disobedience like growing a moustache, but grows in commitment and brutality until the climax of the story.

As the confrontation between the rebels and the establishment intensifies, the film becomes more and more surreal. The headmaster keeps the chaplain in a drawer in his office; a teacher’s wife wanders naked through the dormitories dreamily touching objects; a cache of weapons emerges from under the chapel. This builds to the film’s final scene, where the rebels face off against the establishment at a school benefactors’ assembly, with blue-rinsed ladies and men dressed as medieval knights wielding tommy-guns against the Crusaders. Significantly, and despite Travis frequently wishing aloud for death during the story, the film ends with none of the rebels dead, as if to suggest that they survived despite the odds.

Travis and The Girl share a tender moment

Travis and The Girl share a tender moment

If… manages to do much better than some of its stablemates in its treatment of sexuality. A homosexual relationship between two of the students is matter-of-factly portrayed in a sensitive and loving manner, as a counter to the exploitative treatment of the “fags” (as the servants are known) by the prefects. The negative impact of these boarding schools on the psychosexual development of young men is highlighted when one of the Crusaders confesses that girls make him nervous because “you never know what they’re thinking.”

Rupert Webster as the beautiful Philips, finding true love

Rupert Webster as the beautiful Philips, finding true love

The treatment of women is not perfect, but it is at least better than a lot of other surrealist British comedies (sadly a low bar, but nonetheless). There is only one young woman in the story (Christine Noonan) and she is nameless; she might not even exist, since she seems at times to be only a physical manifestation of the Crusaders’ rebellion. However, she is not a pliant love-interest: she slaps Travis when he kisses her without asking permission, and later on initiates a savage, violent love-play by growling and scratching at him. She wields a tommy-gun alongside the boys at the end of the story, metaphorically indicating that any rebellion must include women if it is not compromised. The abovementioned scene of the naked wife in the dormitory isn’t played for laughs or prurience, but suggests a woman whose sexuality is repressed by patriarchy, and who is coming into her own in later life.

Women's liberation? Christine Noonan wields a gun

Women's liberation? Christine Noonan wields a gun

Religion is a key running theme in the story. The movie begins with a quote from Proverbs, and throughout we see the church existing as an adjunct to, and support of, the state, with regular chapel services reinforcing the school’s messages. However, the boys also engage in ironic hymn-singing as a subversive activity, the weapons cache is found under the chapel, and of course the rebels are identified as Crusaders. The contrast is therefore between a compromised and complicit official religion, and a rebellion which is in the actual spirit of Christianity, supporting the oppressed rather than the oppressor.

There are other elements of pointed social satire. The school’s headmaster (Peter Jeffrey) isn’t the ancient conservative type one might expect, but young, dynamic and talking about science and the challenges of the future, in an implication that all politicians, Labour as well as Tory, are corrupted by complicity with the establishment. There’s a savage scene where a history master (the always delightful Graham Crowden) tries to interest his charges in critical thinking, but in the end gives up due to their lack of response, and simply quizzes them on banal facts and figures, showing how the students themselves participate in their own oppression by rejecting attempts at a more expansive education.

Class struggle: the school assembly

Class struggle: the school assembly

Rising young director Lindsay Anderson makes a virtue of the film’s low budget: shooting the whole story in a single location gives it an appropriately claustrophobic feeling of being cut off from reality. There is a simple practical reason behind the movie’s constant shifts from colour to black and white (namely, that the crew ran out of budget for colour film), but it adds to the sense of surrealism, with suggestions of antiquity and of longing for a past which could never exist.

While the film is already starting to feel like the product of another era, and while it’s not exactly the most subtle of stories, nonetheless it can hold its own with movies made by much more experienced and sophisticated casts and crews. Four stars.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

That's telling them. That society resembles our own, senseless laws rigidly enforced and cruelty for a mistake or deviation. A Clockwork Orange, which I note you were waiting for fifty-odd years ago, showed contention in suppressed families underprivileged families. I wish the issues were more current, but they have in fact lasted from when nobody usually had much to say about them to not having any opportunity to say anything. Galactic Journey is like a time closure in this matter.

Had trouble posting earlier. I remember thinking that the color scenes were the indications of unreality breaking into the eccentric, but realistic view of a boarding school, but I could be misremembering how the movie worked.