by Brian Collins

Our journey through this long (560 pages, in fact) and ambitious anthology continues. The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One is, as Robert Silverberg more or less explains it, a survey of short genre SF from the Gernsback years up to just before the founding of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. These 26 stories are a mix of those the SFWA voted on and those which Silverberg had chosen at his own discretion. The oldest story here, Stanley Weinbaum's "A Martian Odyssey," was published in 1934, while the newest, Roger Zelazny's "A Rose for Ecclesiastes," appeared relatively recently, in 1963. Most of these stories appeared prior to the Journey's advent.

Last time we read "Mimsey Were the Borogoves," a splendid story by C. L. Moore and the late great Henry Kuttner, under one of their joint pseudonyms. What do the next nine stories have in store for us?

Huddling Place, by Clifford D. Simak

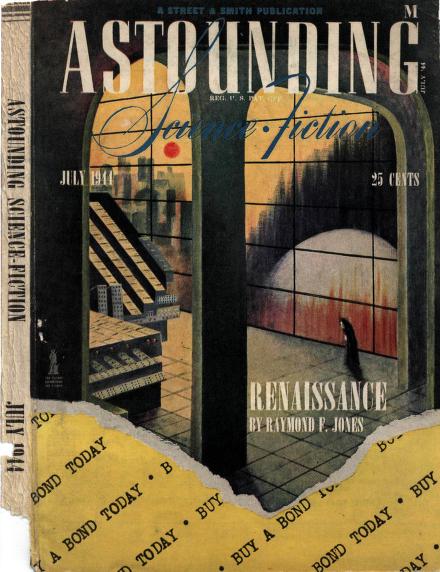

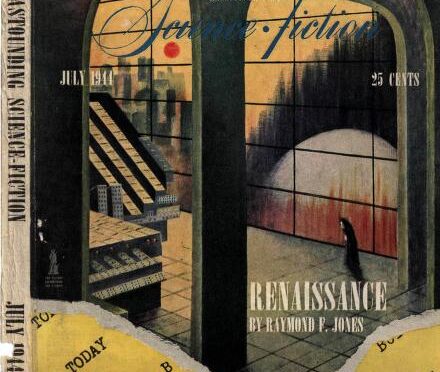

Simak's landmark novel City was published in 1952, although most of the stories comprising it predate the book by several years. "Huddling Place" was published in the July 1944 issue of Astounding, and while it does work on its own, it's best understood in the context of City's timeline. Jerome Webster is a brilliant doctor who tragically also suffers from agoraphobia, in a future where urban life on Earth is dying and people are living farther apart from each other on average. Jenkins, a robot butler who serves the Websters, is a recurring figure in City, although you wouldn't guess it from just this one outing. Simak has garnered a reputation for being "hokey" and unassuming, which makes the grimness of Webster's dilemma rather shocking to read now. The conflict is simple, and there are only a few characters, this being much like a one-act play; but Simak sticks the knife in the reader and twists it with such expertise that the simplicity becomes an asset.

And the ending sent chills down my spine. Five stars.

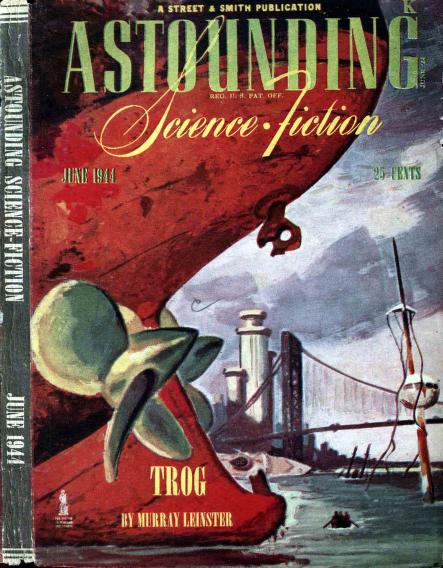

We go slightly backwards, to the June 1944 issue of Astounding, for what is probably Fredric Brown's most famous story, despite it being in some ways uncharacteristic for the author. You may recall (or maybe not) that Brown tended to write short and rather humorous SF stories; but "Arena" is a novelette, and also quite serious for Brown. The premise is simple: a human space fleet has come face-to-face with an equally powerful alien space fleet. When it looks like both fleets are about to blow each other to smithereens, a third party (some kind of higher intelligence) intervenes. Bob Carson of the human side is teleported to a mysterious desert planet with blue sand, to fight off with a warrior from the alien side. Winner take all. The loser will not only die, but so will their entire race. "Arena" was credited as the inspiration for the Star Trek episode of the same name, albeit their endings are different. While it treads no new ground, and while its implied politics are odious (the aliens are clearly stand-ins for imperial Japan), its entertainment value is hard to deny.

Four stars.

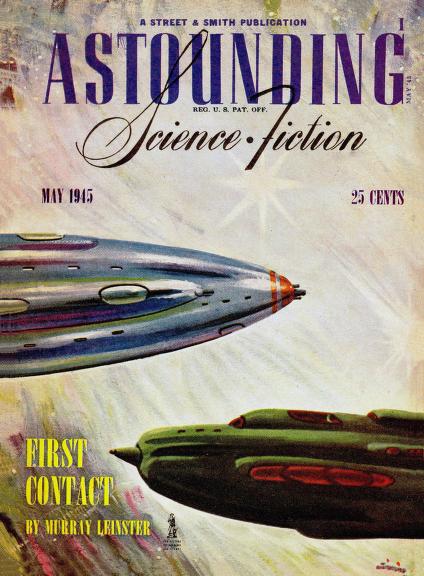

First Contact, by Murray Leinster

Murray Leinster is a pseudonym for Will F. Jenkins, but we all know him by the former name. "First Contact" appeared in the May 1945 issue of Astounding, as part of an impressive run of stories (see also "A Logic Named Joe" and "Pipeline to Pluto") as by either Leinster or Jenkins. I remember the X Minus One adaptation of this story from back when I was in high school, although the ending had been changed drastically. The premise is just as simple as that of Brown's "Arena," and these two stories being placed back-to-back in the book is an ingenious move on Silverberg's part. Once again human and alien ships meet, but this time by accident, and each ship is by its lonesome. These are both intelligent races, but they do not have a shared language—or so it seems. Again, the dilemma is quite reminiscent of Star Trek, albeit Leinster anticipates that show by a good 20 years. Leinster takes a radically different approach from Brown with how one ought to deal with intelligent alien life, and it's an approach that I think will speak more to today's readers. Personally, I loved it. The technique is undeniably of the 1940s (the way the human shipmates talk, for instance), but the actual substance of "First Contact" still reads as modern.

Five stars.

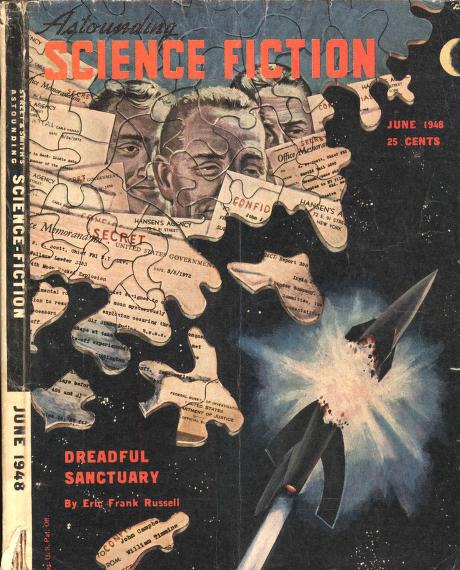

That Only a Mother, by Judith Merril

This is the only story in the book solely written by a woman, which says something either about the field's history (by that I mean its penchant for male chauvinism) or the author's preferences (his penchant for male chauvinism). "That Only a Mother" was Judith Merril's first story, appearing in the June 1948 issue of Astounding, and it's almost certainly her most famous story to this day, although I've never quite been able to wrap my head around why this one in particular continues to be reprinted with such regularity. A housewife has a baby on the way, but she's also been subjected to nuclear radiation, though her husband insists everything should be fine. The ending is the part that everyone remembers. Merril mostly relates these events through letters, which is a method of storytelling I'm not terribly fond of. A big advantage this story has, aside from the ending being memorable in its grotesquery, is that it showed how a nuclear scenario might affect domestic life, in a way that seems less in line with Astounding and more so with Galaxy, which launched just two years later.

A high three stars.

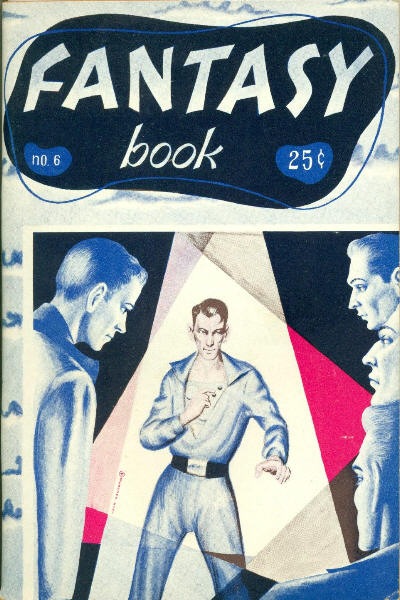

Scanners Live in Vain, by Cordwainer Smith

The book gives the copyright date of this story as 1948, but "Scanners Live in Vain" was published in a little magazine called Fantasy Book in 1950, though I can't find the issue month. The late Cordwainer Smith (alias for Paul Linebarger) was one of the few true mavericks of genre SF, and "Scanners Live in Vain" was his first story. This is a remarkable debut, if also bloated and a little too overwhelming. Writers, both in the '50s and now, find workarounds for how humanity might traverse the stars as painlessly as possible; but for Smith pain is the name of the game. Martel is a Scanner, which is to say he's basically an astronaut whose senses are selectively numbed so that he may survive "the Great Pain of Space." However, Martel and his fellow Scanners run into an existential problem: a new method of space travel that, if successful, would render their grueling sensory deprivation obsolete, and so put Scanners out of a job. I'm simplifying the plot massively; the truth is that Smith not only gives us a very different depiction of space travel from the norm but spins a flew plates while doing so. Despite being the first story set in Smith's Instrumentality of Mankind universe, it's not the most accessible; but the effort is well worth it.

Incidentally, a very young Jack Gaughan did the cover for this issue of Fantasy Book, illustrating Smith's story. That's right, a single issue of this long-forgotten fanzine helped kick off the careers of two major talents.

Four stars.

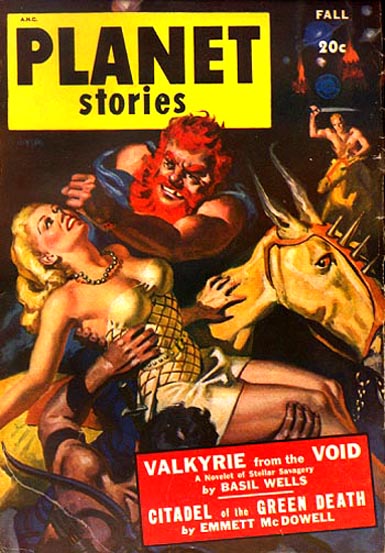

Mars Is Heaven!, by Ray Bradbury

Bradbury has barely written anything worth a damn in over a decade, but back in the '40s and early '50s he was a hungry young talent. "Mars Is Heaven!" appeared in the Fall 1948 issue of Planet Stories, and will strike many as familiar, since it appeared in The Martian Chronicles under a different title. Bradbury's version of Mars barely counted as SFnal, even in 1948, and in the case of this story it's a Mars that borders on outright fantasy. An expedition team has landed on the red planet, only to find, once they emerge from their ship, that it's not so red after all—in fact it resembles rural Illinois far more than Mars. The explorers find people from their past lives, even those they know to be dead, and they know something is up but they can't quite put a finger on it. The twist is apparent, but it still manages to be chilling. This would have made for a good Twilight Zone episode. My problem with Bradbury is that he often overindulges in sentimentality; but "Mars Is Heaven!," which is really as much horror as it is SF, sees him on good behavior.

Four stars.

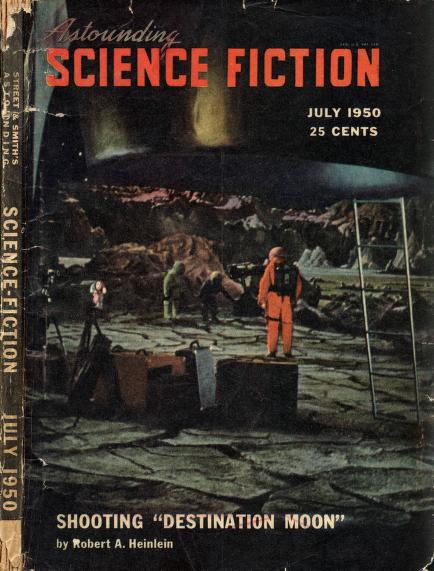

The Little Black Bag, by C. M. Kornbluth

C. M. Kornbluth died in 1958, at just 34, but he had already written a lifetime's worth of short fiction. "The Little Black Bag" appeared in the July 1950 issue of Astounding, and it seems to be set in the same grim future as another Kornbluth story, "The Marching Morons." Humanity has collectively declined in intelligence, leaving even important hospital work to be done via automation. One of these automated medical kits gets sent back to what would have been the present day, left in the hands of a drunken back-alley doctor and a young woman who has plans of her own. Kornbluth's view of humanity is—let's say dim. The fact that "The Little Black Bag" was published in Astounding is a bit of a surprise, given that Kornbluth would mostly move over to Galaxy and F&SF; but it's also quite a bleak story, one which does not have a hero and which is bathed in blood and nefarious scheming. That it's also a little too long for its own good does little to offset it being one of the darkest stories in the whole book.

Four stars.

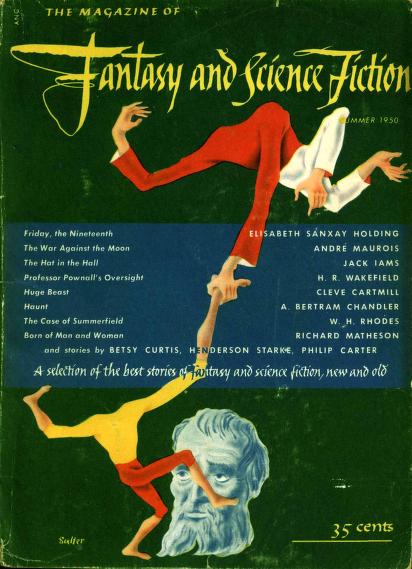

Born of Man and Woman, by Richard Matheson

Matheson is doing well for himself, having written quite a few film and TV scripts. It's easy to forget that he started writing short fiction, with "Born of Man and Woman" being his first story, published in the Summer 1950 issue of F&SF. This is very short, only being a few pages, and it's arguably not even SF. We read the diary entries of some child, who is apparently afflicted with some horrific mutation, and who lives chained to the wall in his parents' basement. It's one of the most unnerving, and at the same time one of the most touching stories I've ever read; and while Matheson has since moved on to bigger and better things, there's purity to "Born of Man and Woman" that understandably has made it one of the most popular stories in F&SF's history.

Five stars.

Coming Attraction, by Fritz Leiber

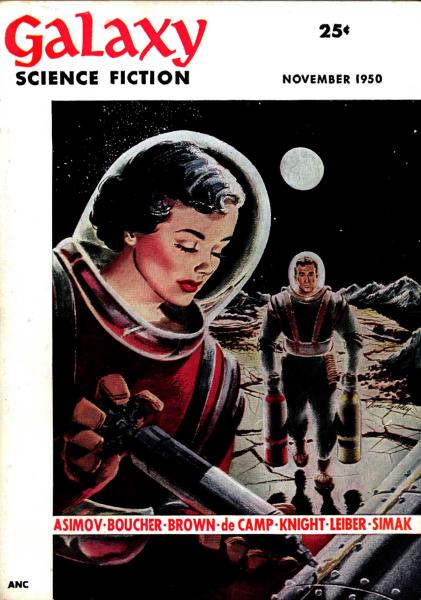

By this point, at the end of 1950, two of Astounding's biggest rivals had made it to newsstands: F&SF and Galaxy. "Coming Attraction" appeared in the November 1950 issue of Galaxy, only its second issue, but Fritz Leiber was already a veteran of the field by this point. "Coming Attraction" is a strange amalgamation of science fiction and detective fiction clichés, yet it's not a mystery and there is no detective figure. 20 years later and it still reads as unique, although I do sometimes wonder if, as technology advances and the Cold War progresses, we might see more SF-detective stories like this one. The premise is that an Englishman comes to America as a tourist, but he finds a very different America from what we now know, World War III having transpired and with parts of the country being irradiated. Hazmat suits became so deeply associated with American culture that they caught on to a degree as a fashion statement, with women often choosing to wear protective face masks in public. It's light on plot, being more concerned with setting a tone and a certain image (a femme fatale whose face is hidden) in the reader's mind.

But Leiber is a master at this sort of thing.

Four stars.

Exceptional Quality… So Far

Five out of the nine stories covered in this segment are from Astounding, but as we move deeper into the '50s it should become apparent that this supremacy will not last much longer. F&SF launched in the fall of 1949, with Galaxy following almost exactly a year later. The first half of the '50s saw a truly staggering quantity and diversity and SF being published, with well over a dozen magazines active in the US in 1953 alone; yet this diversity of output goes pretty much unseen in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One. In part this can be attributed to about half the stories included being the result of a popularity contest on the SFWA's part. People who are now hardened professionals were once hungry readers themselves, and they likely would have found their favorite stories in a magazine that sold well compared to one that didn't. The exceptions, such as the Bradbury and Smith pieces, can, for instance, be attributed to Bradbury still being one of the most famous American authors, be it in or out of SF. "Scanners Live in Vain" gained notoriety, if I remember correctly, from being included in a hardcover anthology that Frederik Pohl had edited many years ago. Smith himself, while he may be dead, is still a much-admired figure.

Because this massive book is partly the result of a popularity contest, in which authors reflected on a field whose formation they themselves helped to shape, there is naturally some bias. Not to mention, it seems like everyone feels like they owe John W. Campbell a goddamn favor. These are the stories that Silverberg and the rest of the SFWA consider to be important, but they're not necessarily the best. Fritz Leiber has written better stories than "Coming Attraction" while "Huddling Place" isn't even the best story from City (which really speaks to that novel's quality).

Nevertheless, being about two-thirds into this book, you would be utterly foolish to not get yourself a copy.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

Goshes ! This is an excellent article. Yeah Campbell at Astounding set up the goals for modern prose science fiction 1938 to 1950, … then fumbled. All the great work in SF went to Galaxy and F&SF. The innovation and invention in the 1950s is breath taking. Great SF prose was yet to come, but me-thinks just about every basic story idea there could in SF was fabricated in the 1950s.

And the reason for JWC fumbling the ball can be explained by one word: Dianetics.

In 1950 huge sections of the May, August & October issues (along with January 1951, which due to Street & Smith's publishing schedule was another 1950 issue in all but name) were taken up by the new science of the mind.

Campbell alienated Alfred Bester , in JWC's Street and Smith office by forcing him to read Hubbard's nonsense. Campbell irritated Heinlein at a home dinner with his tweaking of Hubbard. Then JWC indulged in his pseudoscience , "Hieronymus machine" and Dean Drive, which soured a lot of people.

Heinlein and Asimov tolerated him (Asimov he still liked his old mentor). It was noticeable that it was Galaxy that was publishing Dick, Pohl, Kornbluth, Bradbury, Bester … lots … with new and clever SF.

In later life, Asimov expressed the debt he felt to Campbell as the man who'd 'created' him as a writer — Asimov being fairly honest about how he'd been an obviously intelligent kid without apparent writing talent whom Campbell had molded into a writer as much for an experiment as anything else — while noting that he'd found Campbell's politics and crankery increasingly unbearable. Indeed, in the 1950s he often placed his short stories with Robert Lowdnes's second and third-tier magazines rather than deal with Campbell, though ASF was still the top-paying market.

Campbell's problems went way beyond dianetics. Probably Asimov's fellow Futurian Donald Wollheim — the most successful Marxist publisher in American history — had the correct diagnosis back in the 1940s: Campbell was always a fascist. If a glib theory about the inferiority of some human group or other appeared, Campbell was usually attracted to it like a fly to feces, so by his Late Senile Period in the 1960s he was writing editorials about how the blacks in LA were rioting because they missed being slaves and how cigarettes were good for you and their carcinogenic properties were a smear by the anti-tobacco lobby. (Shortly before he died from lung cancer at the age of 61.)

And yet. Even in his Late Senile Period, Campbell was responsible for printing Herbert's Dune and Tiptree's first few stories, which are still influences today. In the 1940s, his influence was absolutely transformative — even ASF's covers under Campbell looked like nothing in American magazine SF before.

In the end there are some figures whose contributions are so central — forex, Richard Wagner in the arts or Linus Pauling in the sciences — that you just have to hold your nose when it comes to their politics and accept that that's who they were.

JWC's influence on SF art is unjustly forgotten. ASF from 1938 on started having , covers , at least, that differed from the BEMs and Bra Bras so common on the pulps of the day. In time Campbell found artists like Cartier, Kelly Freas and Ed Emshwiller. By the 1950s ASF displayed 'domesticated' science fiction illustrations. The writers had mastered this kind of verisimilitude in the 1940s , now it had graphic expression. As far as I know it was JWC who was responsible for this.

Al J.: 'As far as I know it was JWC who was responsible for this.'

I agree. And not just verisimilitudinous/semi-realist, but also outright modernist stylization and design choices sometimes.

Look at this as early as September 1940 (!) forex.

Or this in June 1943 —

https://www.luminist.org/archives/SF/AST/AST_1943_06_L.jpg

These alongside the well-known 'classic' 1940s ASF covers from the 1940s, such as for Kuttner-Moore's Fury in 1947 —

https://grangerartondemand.com/featured/astounding-science-fiction-1947-hubert-rogers.html

Or for Heinlein's Waldo in 1942 —

https://www.luminist.org/archives/SF/AST/AST_1942_08_L.jpg