We're breaking up this month's Galactoscope in two—and the dross leads the back. The next three books are all sub-mediocre, but the reviews are well worth the price of admission!

by Victoria Silverwolf

Apologies to Canadian songbird Joni Mitchell for stealing the title of her song, which appears on last year's album Clouds.

Singer Judy Collins released a version in 1968, but Mitchell wrote it, so this is the definitive version. The cover of the album is a self-portrait, by the way.

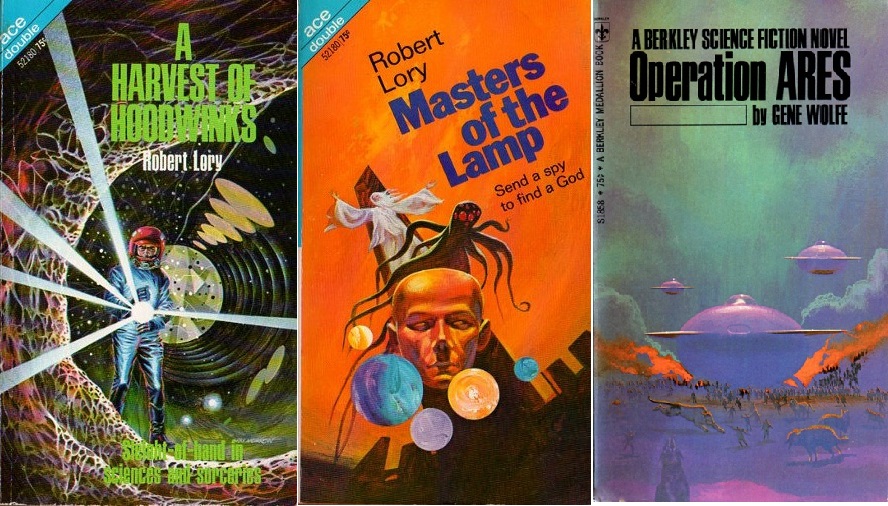

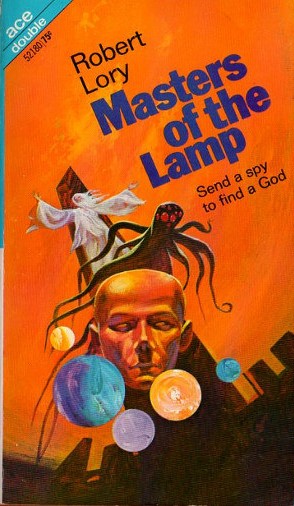

I mention this because both sides of the latest Ace Double paperback (number 52180, seventy-five cents at your local drugstore) are by the same author, Robert Lory. One is a collection of short stories, the other is a novel. Let's look at the first side, now.

Cover art by Gray Morrow.

An introduction by the author explains the title of the collection by claiming that all these tales feature deception of some kind. Many of them appeared in various magazines, others are original.

Archimedes' Lever (retitling of The Courteous of Ghoor, If, February 1968)

Cover art by Vaughn Bode.

A seemingly ordinary guy gets transported to an alien world. The humanoid who greets him tells the fellow that he has the power to move things around the universe with his mind. The man is supposed to train his inherent talent to the point where he can move Earth to another star.

Why? Because the sun is about to blow up. Of course, there's more going on than meets the eye.

My esteemed colleague David Levinson gave this yarn a high two stars, calling it a nothing of a story. Fair enough. Readable, forgettable.

Mar-ti-an (F&SF, May 1964)

Cover art by Ed Emshwiller.

A Martian criminal is exiled to Earth and winds up with a bunch of hillbillies.

Boy, this is bad. The Noble Editor gave it one star, suggesting that the editor find better joke stories. I can't argue with that. The hillbilly stereotypes make Snuffy Smith look like a refined, elegant gentleman of grace and intelligence.

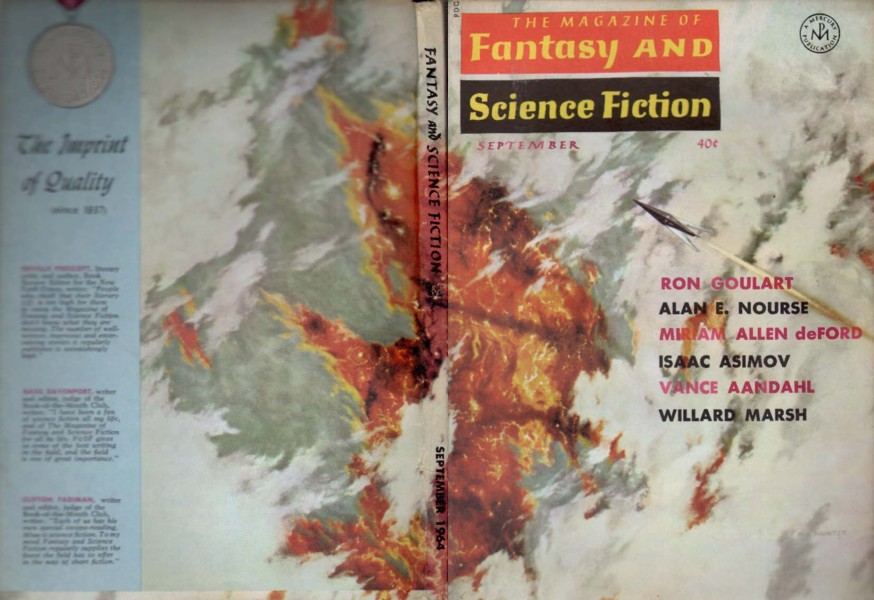

The Star Party (F&SF, September 1964)

Wraparound cover art by Mel Hunter.

The narrator and his wife attend a cocktail party. In attendance is a mystic, who can accurately describe someone's astrological sign, in detail, just by looking at that person. The woman, however, is a mystery.

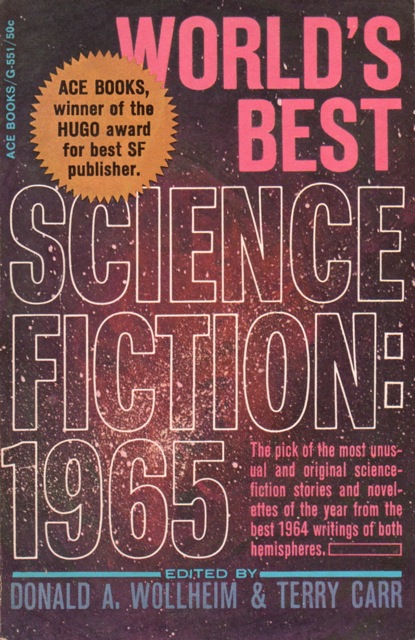

The Noble Editor was more generous with this story, giving it three stars. Heck, it even wound up in World's Best Science Fiction: 1965, edited by Donald A. Wolheim and Terry Carr.

No cover art credit.

My esteemed colleague John Boston reviewed the above book, and called Lory's contribution an annoyingly slick rendition of an original but silly idea.

The first time I read this, I also found it to be a trivial tale with a goofy twist. On going over it again, I began to appreciate the author's biting satire of the decadence of upper middle class folks, the men lecherous drunks and the women shameless flirts.

Overall, three stars is about right.

Futility is Zuck (original)

A robot at a factory slices a guy into a zillion pieces. It seems the robots are unionized, and view the human worker, who gives them oil, as unacceptable. They also refuse to accept a cheap machine to do the job, and insist on an expensive one. What can management do?

A nutty, if somewhat grim, satire on labor relations. The strategy that management uses to defeat the killer robot is pretty wacky, too.

Two stars.

Snowbird and the Seven Warfs (original)

Somebody from another world shows up out of nowhere and forces a guy to play a televised game show. Each wrong answer causes one of his body parts to vanish, without any apparent harm. It's all a big mistake, but how can the game show host make it up to the guy?

Very broad comedy with a punchline that turns it into a mildly dirty joke.

Two stars.

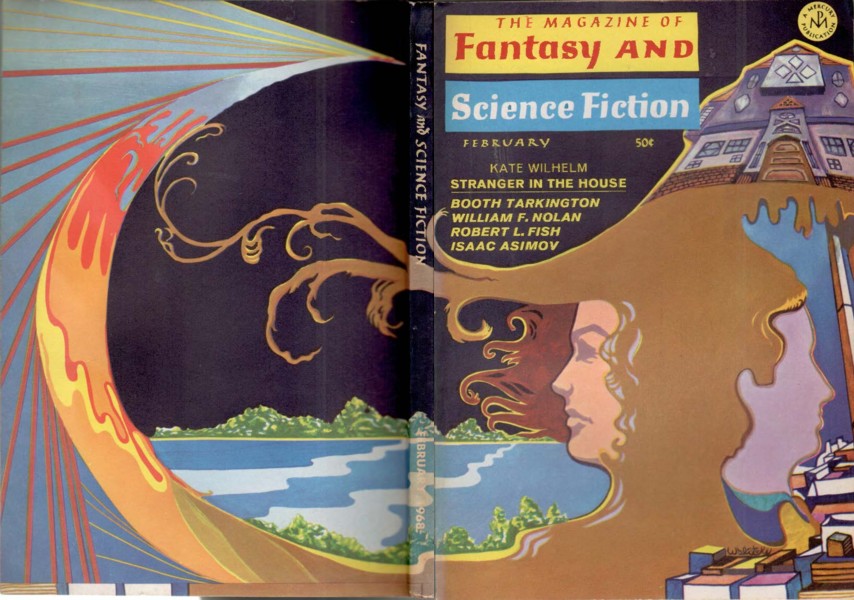

The Locator (F&SF, February 1968)

Wraparound cover art by Ronald Walotsky.

A fellow very carefully records every place where a genuine UFO from outer space has landed. He predicts, with great accuracy, when and where another one will show up. Maybe a little too accurately, in fact.

An extended joke with a decent punchline. The Noble Editor gave it three stars. He must have been in a good mood. It's OK, but trivial.

Two stars.

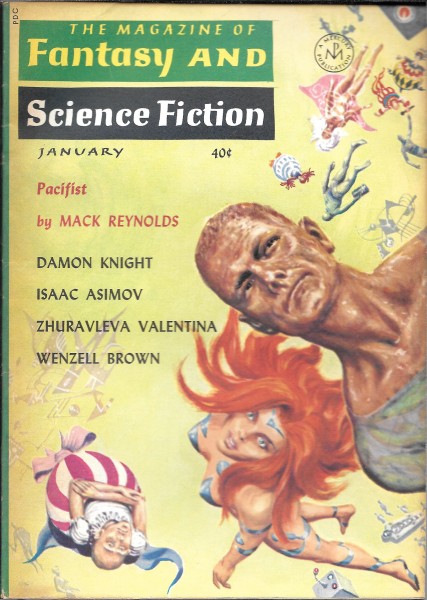

Appointment at Ten O'Clock (F&SF, January 1964)

Cover art by Ed Emshwiller.

A man finds himself living the same morning over and over again, each time ending in his death. What's the little man in the green hat got to do with it? And how can he change the situation for the better?

The Noble Editor awarded this one another three stars, and I agree. The premise is intriguing, in a Twilight Zone kind of way. The conclusion is a bit risqué, but tasteful. Not bad at all.

Only a God (original)

Gigantic reptilian aliens worship an equally huge bird, to whom they offer members of their own species as sacrifices. A tiny being (obviously a human being) shows up. Could this be a new god?

A rather deft satire on religion. The aliens quote verses from their holy book in a way that suggests the Bible. Only the most conservative persons of faith should be offended. The target of the author's poison pen is more those who would manipulate religion for their own ends than faith itself.

Three stars.

The Fall of All-Father (original)

Among some cavepeople, one man has access to all the women. A man and woman show up in a saucer of sorts. (Spaceship or time machine? I'm not sure.) One caveman wants the new woman for himself, since he can't defeat the guy who has all the women. The visiting woman balks at that, but the pair help him in another way.

Eh. Not much to say about this one. Not very interesting.

Two stars.

Because of Purple Elephants (original)

A ten-year-old boy and his four-year-old brother go exploring. They discover a crashed spaceship with one alien left alive but near death.

People on Earth already know that the aliens have been sending scouts, trying to discover if they can survive there. If so, they plan to take over. The response of the Earth authorities is to have them killed on sight.

The dying alien asks for water telepathically. How should the older boy react?

I have to admit that this one took me by surprise. I was expecting a sentimental ending (the boy saves the alien's life, the two species learn to live together) or maybe some kind of humorous punchline. What I didn't expect was a conclusion that really hit me hard.

For that reason, a rare four stars for this author.

Rolling Robert (original)

A kid is born with a round bump on his elbow. Eventually, the bump absorbs the rest of his body, so he becomes a living ball. For some reason, eggheads think he's a genius. A real kid genius challenges him to a duel.

This is extremely silly stuff. I can imagine the author giggling as he wrote it.

Two stars.

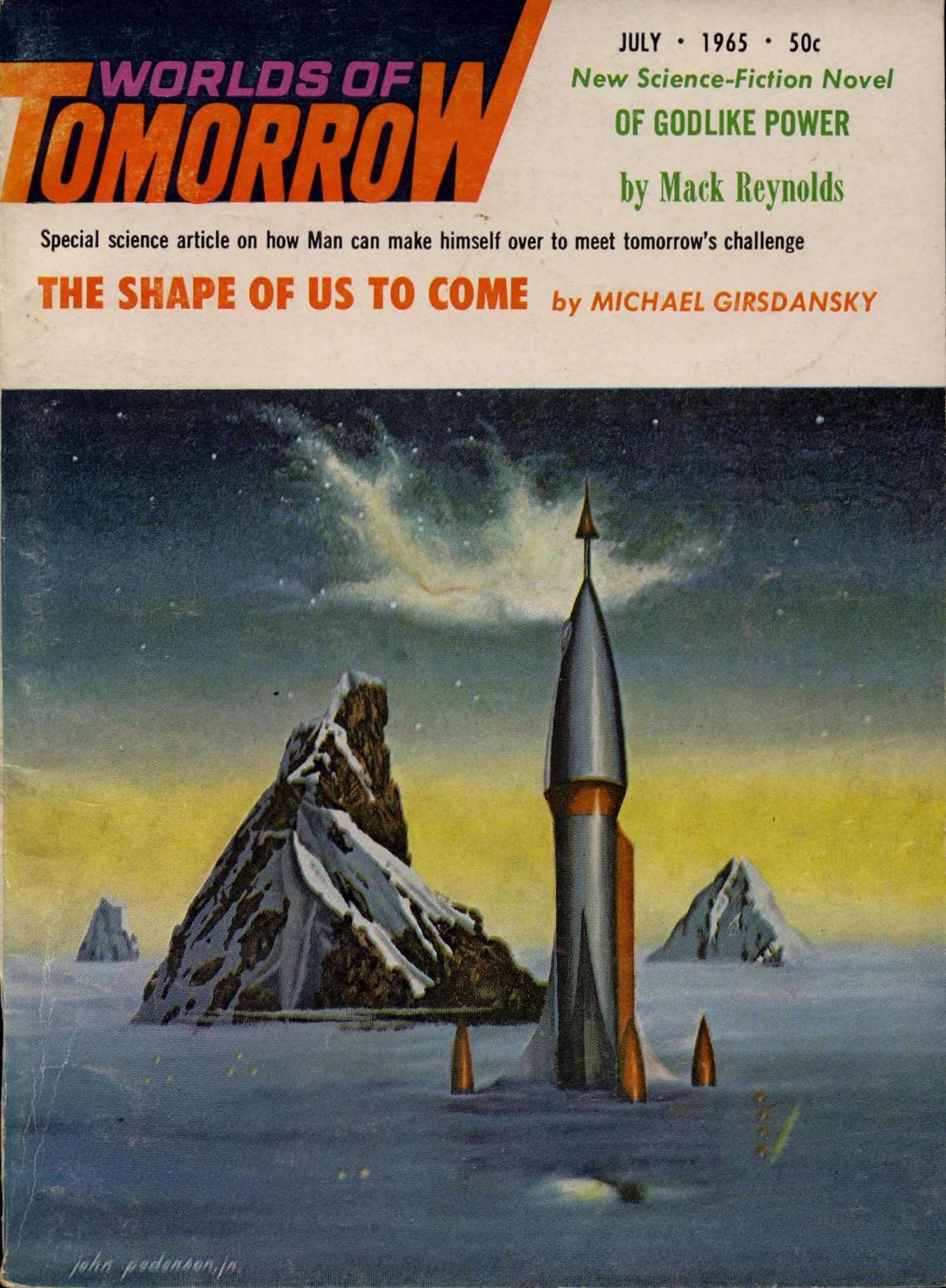

Debut (retitling of Coming Out Party, Worlds of Tomorrow, July 1965)

Cover art by John Pederson, Jr.

I reviewed this story myself, so let me just repeat what I said then.

This brief tale begins with a young woman getting ready for the event mentioned in the title. Our first hint that something strange is going on is the fact that she's stark naked in front of her parents. The ceremony is also full of nude women.

I dare not say anything else about what happens, except to mention that the shock ending is an effective one. This is one of those stories that depends entirely on the twist in its tail.

Three stars.

Overall, the collection stumbles to reach two stars. Too bad, because the author is obviously clever, but too fond of twist endings and comedy that isn't as funny as he thinks it is.

Will he be better at a longer length? Let's flip the book over and look at the other side, now.

Cover art by Jack Gaughan.

Our hero works for a galaxy-wide intelligence agency. Yep, this is another James Bond imitation, with space opera trappings.

Illustration by Gaughan also.

After surviving an assassination attempt, he gets an assignment to find out why two other agents have been killed in so-called accidents.

The spy agency is run by a biological computer, who tells him that information has been leaking out of the organization. Nobody is free from suspicion, so the computer tells him to avoid speaking to his human boss about this.

A beautiful female agent from another organization, our mandatory Bond Girl, works with him. She's not supposed to know everything about what's going on either.

They trace the leak to a planet where religious eccentrics of every imaginable variety are welcome. Complications ensue, with lots of people getting killed. It all leads up to a cataclysmic climax.

I'm not sure if the author is pulling my leg or not. The novel isn't funny enough to be a spoof, really, but some things are really outrageous. The pace makes Keith Laumer looks leisurely. Some scenes seem to jump around from one planet to another as if it's a walk to the corner store. It's a quick read, anyway.

Two and one-half stars.

by Brian Collins

A debut novel, for most authors, is like a rite of passage, especially for those writing SF, where historically not too much should be bet on a debut novel being anything above average. Does anyone remember Robert Heinlein's first novel? I believe it was Fifth Column. How about Frank Herbert's first novel, The Dragon in the Sea, which wallows in obscurity compared to the titan that is the Dune series? Granted that there are exceptions, like Joanna Russ's Picnic on Paradise (although it's more of a novella), which are memorable enough to be worth considering as indicative of a talent for novel-writing.

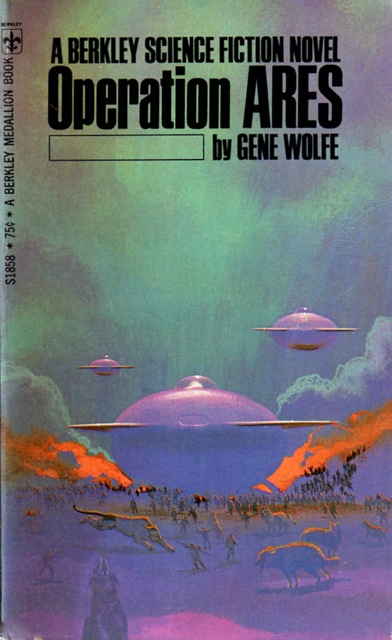

Unfortunately, Gene Wolfe's debut novel is a member of the majority—arguably even more so than most, since we already know that Wolfe can be quite good at short lengths. Over the past year or so, Wolfe at his best has written some pretty unique and at times haunting SF. He's still early in his career as a writer, but he clearly has plans on hunting some intellectual big game, whereas some of his peers do not. Operation ARES is, unlike the best of Wolfe's short fiction, a poor misshapen thing which does not have the elegance in style or substance that we know Wolfe is capable of.

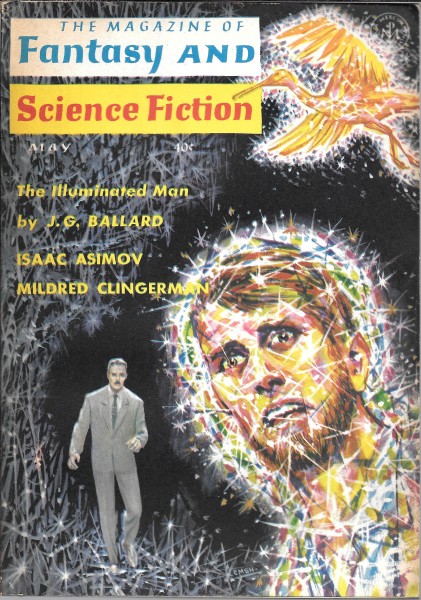

Operation ARES, by Gene Wolfe

Civil unrest and anti-technology sentiments among the public have gotten to the point where the federal government decided to suspend the Constitution and abandon its colony on Mars. Cops have been replaced with peaceguards, and without the right to bear arms, civilians are unable to defend themselves even against wild animals. The Pro Tem Government was supposed to be a temporary setup, as an emergency, but things have been like this for 20 years and there is no end in sight. The US has devolved into a moderately socialist nanny state that colludes with the Soviets, while the Chinese, evidently still under Maoism, are looking for a weak point against their Soviet rivals. This is all, at least according to Wolfe, quite bad. We can infer that this is a dystopian situation because our hero, John Castle, 24-year-old teacher and technology supporter, starts out as already having a bone to pick with the Pro Tem Government.

Then, one day, the Martians decide to send a message to Earth.

After 20 years of silence and being left to fend for themselves, the Martian colonists waste no time in finding a capable ally with Castle. "But then," you might be asking, "what is ARES, and what does that have to do with the Martians?" ARES is an alleged rebel group sympathetic to the Martians, with the aim of overthrowing the Pro Tem Government. I say "alleged" because while rumors persist of its existence, nobody has captured a confirmed ARES agent, making it possible (even probable) that ARES is a paper tiger of an organization. That ARES might not exist doesn't stop Castle from joining its ranks. Emil Lothrop is Castle's Martian contact and the one who ultimately convinces him to join ARES. Then there's Anna Trees, Castle's love interest, although we're told much more about their relationship than we see the two actually interact.

Operation ARES reads in part like a protracted right-wing hallucination, in which Wolfe seems to be reacting to some policies from the Johnson administration; but, of course, Johnson is no longer in office, although in Wolfe's defense, he had probably written this novel a couple years ago. A novel having bad politics is not a point against it per se, since after all, I'm still convinced Heinlein's The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress is one of the major SF novels of the past decade. I'm also not a Marxist-Leninist or Maoist, so I'm not much bothered by Wolfe's apparent ambivalence toward the Russians and Chinese, though it must be said that there is some racism aimed at the latter group, to the novel's detriment. Despite being on the side of the good guys, there's still a whiff of yellow peril about how Wolfe's characters refer to the Chinese, with Lothrop dismissing them as a bunch of "semi-illiterate Orientals" who much prefer quantity over quality. This kind of generalizing, alongside the novel's overt conservatism, strikes me as being a step or two below Wolfe's intellectual caliber.

The bigger problem, which anyone of really any political stance will be forced to notice, is that Operation ARES barely holds together as a novel. There are individual good scenes, especially when viewed with hindsight (Wolfe sometimes rewards the reader by withholding a scene's full importance until after the fact, in so making the reader feel almost like a collaborator with the novel), but there are too many characters and factions at play for a novel that only clocks in at 208 pages. I suspect that Wolfe had envisioned a longer novel, but someone at Berkley Medallion must have gotten scared with the result—mind you that it would be hard to blame them, because I think that even if Operation ARES was, say, 250 pages instead of just over 200, it still wouldn't be very good. While Wolfe is able to pack some big ideas and emotions into short stories that run 10 or 15 pages, he is (at least with this first attempt) unable to do the same with a full novel. There was no point in Operation ARES where I felt as attached to the characters as I did in, say, "The Horars of War," or more recently "The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories."

Wolfe reminds me of another author and fellow Orbit contributor, the very young but promising Vernor Vinge. Last year Vinge made his novel debut (also from Berkley Medallion, incidentally) with Grimm's World, which also wasn't very good, albeit not for quite the same reasons. The first stretch of Vinge's novel is rather strong, but then it loses steam and direction. Wolfe's novel, on the other hand, feels much more like a patchwork, being like a quilt that's made of some individually good and pleasing pieces, but with other pieces sewn alongside them which simply do not work in tandem. That Operation ARES is also Wolfe's crankiest and most overtly right-wing story to date doesn't help.

Two stars.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

The difference in the level of achievement between, as you say, Wolfe's 'The Doctor of Death Island And Other Stories' and, on the other hand, ARES is striking. Stylistically, they're recognizably from the same author, but the lack of any convincing architecture in Wolfe's attempt at a novel — and that architecture could have been as simple as a story line that made sense (aka a plot), though it didn't have to be that — is fascinating. Also, instructive. Novels generally need architectures and there are writers who can write great short stories — John Cheever from this period of American mainstream Lit, for example– who just can't seem to figure that out or even actively resist it.

I think Heinlein's first novel was "Beyond this Horizon" though there are rumors he wrote one before that that never got published (man, I bet if that manuscript is ever found, it will get published now!).