by John Boston

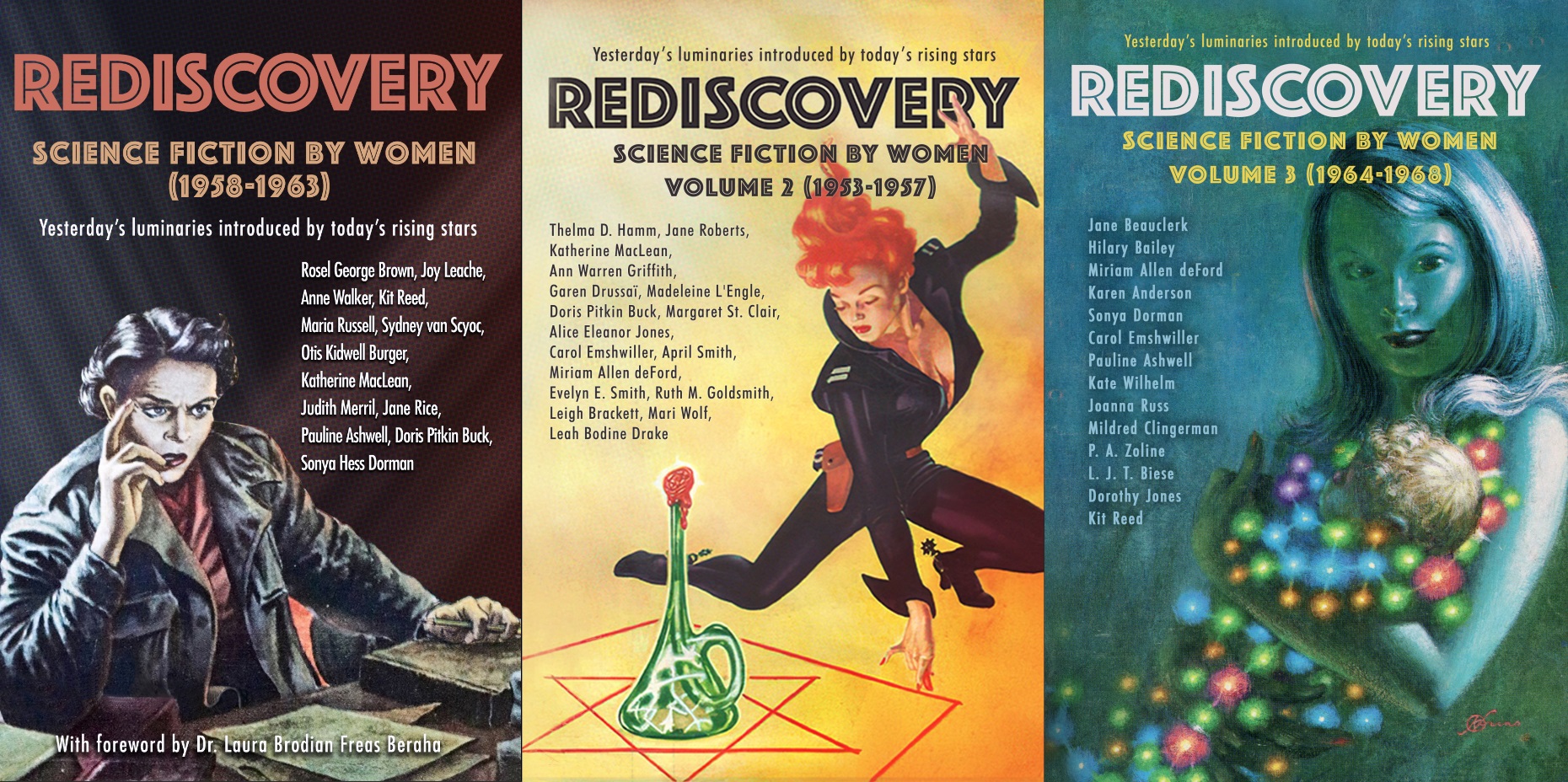

Entering the Stengel Zone

The April 1968 Amazing displays a deep incompetence at the most basic tasks of assembling a magazine. For starters, this April issue—identified as such in two places on the contents page—is dated June 1968 on the cover, a blunder that will likely cost the publisher when the next issue appears. Further, Harry Harrison’s editorial, titled Unto the Third Generation, has apparently been accidentally truncated. It describes “first generation science fiction, or SF-1” (up to the early forties, relying on novelty of ideas), and then “second generation science fiction, SF-2” (starting in the forties with—it says here—Kornbluth, Pohl, and Wollheim, and reexamining old themes), and then . . . stops. Abruptly. What happened to SF-3, the Third Generation of the title? There’s no continuation anywhere in the magazine, nor is there any hint that Harrison meant to stop short of this third generation or continue the editorial in some future issue.

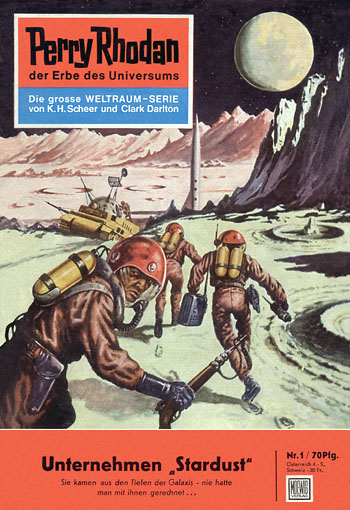

by Johnny Bruck

Other evidence of chaos in the composing room is that the texts of two items in the magazine conclude on the inside back cover, which is usually devoted to advertising. This inside cover has microscopic top and bottom margins, suggesting a last-minute effort to correct earlier miscalculations and cram everything in (except, of course, the end of the editorial, seemingly lost to follow-up). And the proofreading, which has been routinely abysmal since before Sol Cohen took it over, if anything seems to be getting worse. In particular: The very first sentence of the editorial reads “In the beginning there was the word, and it was scientifiction.” Except as printed it actually reads “scientification.” You’d expect in this specialist magazine that someone—especially the editor who wrote it—would notice an error that blatant if they looked at it. Apparently, no one is looking.

Legend has it that Casey Stengel, manager of the hapless 1962 New York Mets, asked in exasperation, “Can’t anybody here play this game?” Amazing now prompts the same question.

The news is no better with respect to the magazine’s content. Rumor has it that Harrison upon taking the editorship worked out some amicable arrangement with the Science Fiction Writers of America concerning Cohen’s use of reprints—presumably getting him to pay the authors something. But reprints continue to dominate—they comprise six out of seven of the stories here.

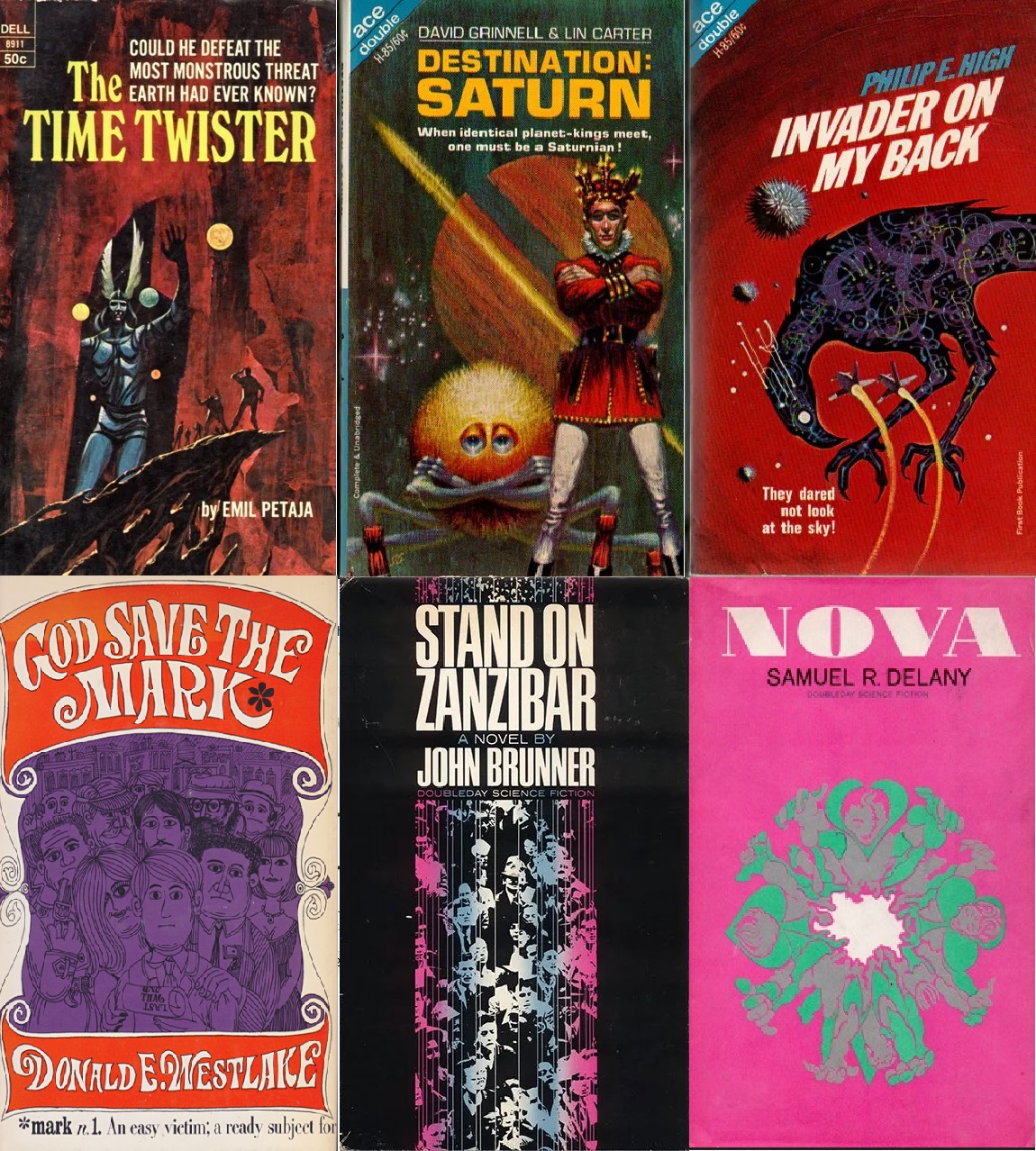

There is new non-fiction material—another “Science of Man” article by anthropologist Leon Stover (see below), and a lively book review column by James Blish, under his pseudonym William Atheling, Jr. Blish virtually disembowels Sam Moskowitz’s book Seekers of Tomorrow, which collects essays on major science fiction writers, earlier published in Amazing before Cohen. Blish’s judgment: “inaccurate, prejudiced, filled with false assumptions and jejune literary comparisons, very badly written and utterly unproofread. If this is scholarship, we could do with a lot less of it.” He makes his case in detail. About the only defense remaining to the book is that it’s better than the competition, since there is none. Blish also reviews Harlan Ellison’s anthology Dangerous Visions with measured praise.

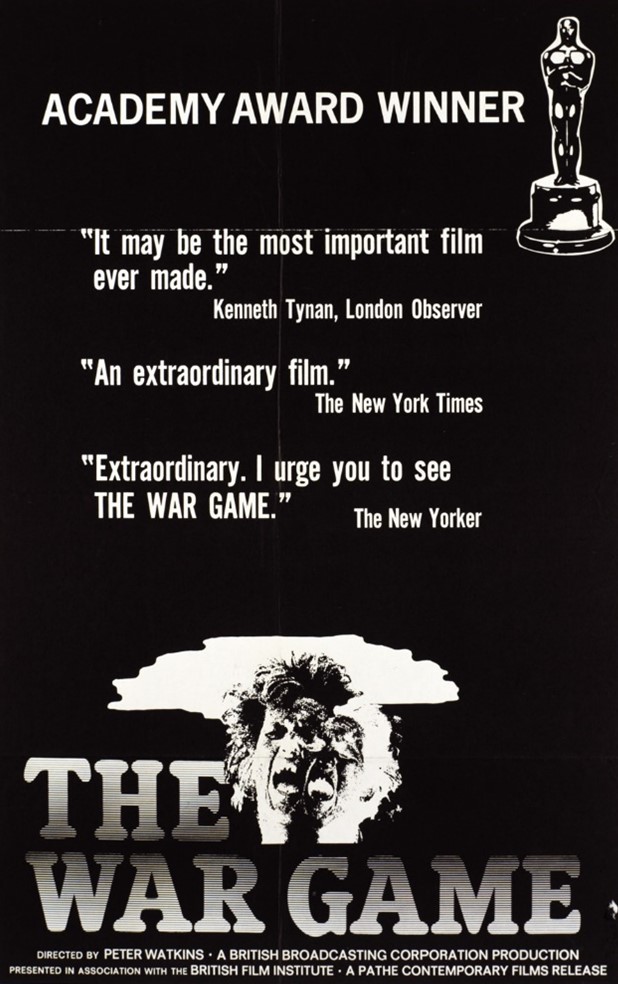

And, on the front, there is another Johnny Bruck cover taken from Germany’s Perry Rhodan magazine, badly cropped, and featuring guys in spacesuits running around with ray guns. Bruck’s work is colorful but cliched, and that is getting old.

All that, before we even get to the fiction! Sheesh.

Send Her Victorious, by Brian W. Aldiss

by Jeff Jones

The only non-reprint story is Brian W. Aldiss’s Send Her Victorious, which at first seems like a slapdash, thrown-together story, but proves to be about a slapdash, thrown-together world. It’s minor Aldiss, odd but quite funny in places. Three stars.

The Illusion Seekers, by P.F. Costello

The Illusion Seekers, a “complete short novel” from the August 1950 Amazing, is bylined P.F. Costello, which is a “house name”—a pseudonym belonging to the publishing company and used by various authors as convenient. This name is said to have been used often by William P. McGivern, but I don’t think this one is his, since McGivern is rumored to be a competent writer.

by W.H. Hinton

The story opens in a small and isolated colony of people suffering from deformities such as soft bones, woody skin plaques, and multitudes of miniature fingers growing from the backs of their hands. But young Randy is normal. Down the road from the east comes a guy named Raymond who calls himself an Illusion Seeker, but won’t explain what that means. He warns that “death will breathe through the trees” in three days, but throws golden dust into Randy’s face and says he will be saved. Sure enough, three days later everybody but Randy is dead. So Randy sets off west following Raymond, discovering that the golden dust has left him with enhanced physical prowess as he fights off wild dogs with an axe. He encounters two survivors from other groups who, hearing his story, tell him Raymond is responsible for the deaths. They all continue west and catch up with Raymond. Randy’s companions kill Raymond. Then they start heading back east in a state of mutual murderous mistrust, have other picaresque but wearisome adventures, and eventually Randy gets the real story of how his world works, which of course makes very little sense.

This story is both repellent and remarkably incompetent, written in a dead, flat style, with a pseudo-plot that rambles on and gives every indication of being made up as the author goes along, all set against a sketchy and implausible background. Overall, it’s a reading experience sort of like the world’s least interesting bad dream, or like listening to a long and tedious monologue by someone who you gradually realize is not all there. It made me wonder whether it’s Richard S. Shaver, Amazing’s foremost ex-psychiatric patient, making a few bucks behind the pseudonym. In any case—one star, a burnt-out husk of a black dwarf.

The Way of a Weeb, by H.B. Hickey

by Robert Gibson Jones

H.B. Hickey contributes The Way of a Weeb (from Amazing, February 1951). A Weeb is a frail humanoid creature native to Deimos who is always scared and always whining about it. They’ve got one on space ship Virtus, to the great disgust of all the crew except Crag, who takes pity on him. But things get tight when the evil Plutonians come after the Virtus, and the Weeb comes through and saves the day. It’s a dreary bag of cliches, professionally rendered. Two stars.

Stenographer's Hands, by David H. Keller, M.D.

The issue’s “Classic Novelet” is David H. Keller’s Stenographer’s Hands, from the Fall 1928 Amazing Stories Quarterly. In broadest outline it follows the template of the earlier-reprinted Revolt of the Pedestrians and A Biological Experiment: humanity’s traditional ways of life get drastically altered, the results are disastrous, and there’s an upheaval to set things right (though the upheaval here is a little milder than in the others).

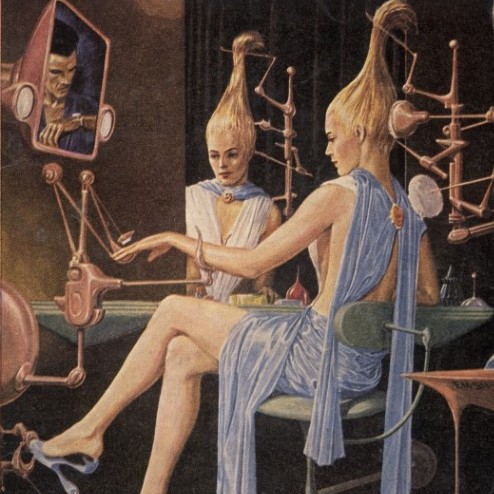

by Frank R. Paul

The president of Universal Utilities is bedeviled by the number of errors his ditzy stenographers make (apparently his business runs on non-form letters), and demands that his house biologist come up with a solution. Easy-peasy: they’ll breed the perfect stenographer, by the hundreds or thousands, firing the less competent of the current flibbertigibets to make room for an army of promising males to balance the sexes. Stenographers who marry and breed will get a free house in a special stenographers’ suburb among other perks. There will be certain other undisclosed manipulations such as providing special food for the kids to help them grow up faster.

Two hundred years later, Universal has achieved world domination economically, with a torrent of flawless letters flowing out from a work force that matures at age 9, marries at 10, and reproduces quickly thereafter. But the daughter and heir apparent of the current company president, having flunked out of college, says she wants a job as a stenographer. She is then appalled at the sterility (metaphorical, of course) of the stenographers’ lives, and says when she’s in charge she won’t stand for it. Conveniently, it is discovered that the stenographers have become so inbred that they are all starting to display nocturnal epilepsy. Never mind! The great experiment is reversed and once more the company's letters will be haphazardly produced by flighty young women of normal upbringing.

So, an obviously terrible idea is belatedly discovered to be terrible and is abandoned. This is not a particularly dynamic plot and nothing else about the story is especially captivating. Two stars.

Lorelei Street, by Craig Browning

Craig Browning is a pseudonym of Roger Graham Phillips (“Rog” to the readership), and Lorelei Street comes from the September 1950 Fantastic Adventures. It's a facile but insubstantial fantasy involving a cop named Clancy who is asked by a passer-by for directions to an address on Lorelei Street, which he provides, later realizing that there is no such street. There are more funny happenings about Lorelei Street. A man who bought a big bag of groceries there was found later in a state of near starvation despite eating them. A woman bought a suit which later disappeared, leaving her on the street in her underwear. A Mr. Calva is the apparent proprietor on Lorelei Street, and Clancy arrests him for fraud. Calva says he’ll regret it. Next day the newspapers describe the arrest of “Calva the Great,” a “hypnotist swindler.” Calva vanishes from court on the day of trial, and when Clancy tries to go home, he finds himself on Lorelei Street, and it’s curtains.

by Edmond Swiatek

There’s more to the plot than that, but not better. Like Phillips’s “You’ll Die Yesterday!” from the previous issue, the story displays considerable cleverness to no very interesting end. Two stars, barely.

Four Men and a Suitcase, by Ralph Robin

Ralph Robin’s byline appeared on 11 stories in the SF magazines from late 1951 to late 1953, most of them in Fantasy and Science Fiction or Fantastic, plus one in Amazing in 1936. Later he made an appearance in Prairie Schooner, a literary magazine published at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln; the story wound up in Martha Foley’s annual volume The Best American Short Stories 1958. He seems to have quit while he was ahead; he has not been heard from since that I can discover.

Robin’s story Four Men and a Suitcase, from Fantastic for July/August 1953, is about some Skid Row drunks discussing what to do with a mysterious object one of them has found. It looks like a giant hard-boiled egg, and when yelled at threateningly displays diagrams on its . . . skin? (No shell.) The first one illustrates the Pythagorean theorem. After several further iterations, one of the characters slaps the egg, with large and regrettable consequences. The main point here seems to be how hilarious poverty-stricken alcoholics are. Sorry, can’t get with it. One star.

The Mechanical Heart, by H.I. Barrett

The issue’s fiction winds up, literally, with The Mechanical Heart by one-story wonder H.I. Barrett, from the Fall 1931 Amazing Stories Quarterly. Inventor Jim Bard has just learned that his heart could conk out any minute. But he wants to complete his telephoto machine! (Actually more like television.) The solution? Make an artificial heart! His assistant Henry, trained in a Swiss watch factory, hops to it. It’s a beauty! And his doctor is persuaded to install it. Jim will carry a case in his pocket with two six-volt flashlight batteries and a watch to time the impulses that drive it. Just wind the watch, and don’t forget to change the batteries!

by Leo Morey

After the surgery, Jim convalesces, and experiments with increasing the blood flow, which he finds highly stimulating. “Have to be careful or he’d have himself cutting all sorts of didoes.” (Dido: “a mischievous or capricious act : prank, antic,” says Merriam-Webster.) But he can’t resist, and starts increasing the flow so he can stay up all night working on the telephoto, and then so stimulates himself that he scandalizes Hilda the Swedish maid and has to be restrained and briefly disconnected by Henry.

At the Associated Scientists’ meeting, to demonstrate both the telephoto machine and the heart, Jim gets stage fright, cold sweat and the works, and then realizes he can increase his blood flow. He sets up the telephoto for a demonstration and discovers—he’s forgotten the C batteries! In desperation, he snatches the batteries powering his heart, and the show goes on, with his machine relaying the picture from a distant movie theatre, while his unsupported heart races . . . for a while. And then, time’s up.

This is the best of a bad lot of reprints—corny, but with at least a bit of period charm, while the others lack charm of any sort. Three stars, grading on the curve.

Science of Man: Dogs, Dolphins and Human Speech, by Leon Stover

Dr. Stover takes on John Lilly’s claim that dolphins can learn to speak English in addition to their accustomed clicks and clacks. He starts out with dogs, which communicate vocally, he says, “but the level of signaling is that of a call system, quite distinct from that of language. A call system is no more linguistic than the system of visual signals dogs communicate to each other by means of facial expression, body movement, and position of the tail.” However: “Language and only language is a symbolic form of communication,” one which allows meaning to be assigned arbitrarily to symbols.

Dolphins? Same story. Their large brain size has more to do with body weight than with intelligence. “How the brains of dolphins function to meet the demands of their environment is not yet known, but it is a sure thing that research will show that symbolic behavior, like language and culture, is not part of that adaptation.” And there’s the rub—“it is a sure thing that research will show.” Stover continues with arguments about the evolution of human intelligence in ways that exclude dolphins, but there’s no way for the lay person to tell how much of it is supported by research and how much is his admittedly informed supposition. Two stars.

Summing Up

Editors change, formats change a bit, but the consistent mediocrity of this magazine abides, firmly rooted in the dominant and seemingly immovable prevalence of reprints of only occasional merit. One wonders how long this can last.

![[February 6, 1970] All We Are Saying Is Give The Peace Game A Chance (<i>The Peace Game, AKA The Gladiators</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/PG10.jpg)

![[October 2, 1969] Darkness, Darkness (November 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/IF-1969-11-Cover-503x372.jpg)

King Idris from a couple of years ago.

King Idris from a couple of years ago. Libya’s new Prime Minister, Soliman Al Maghreby.

Libya’s new Prime Minister, Soliman Al Maghreby. This month’s cover depicts nothing in particular. Art by Gaughan

This month’s cover depicts nothing in particular. Art by Gaughan![[September 26, 1969] Poetry in motion — the Japanese <i>Tanka</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690926image6-600x372.jpg)

![[August 2, 1969] Specters of the past (September 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/IF-1969-09-Cover-494x372.jpg)

Salvadoran President and General Fidel Sanchez Hernandez inspecting the troops.

Salvadoran President and General Fidel Sanchez Hernandez inspecting the troops. A robot carrying off a fainting human woman. It’s not as old-fashioned as you might think. Art by Chaffee

A robot carrying off a fainting human woman. It’s not as old-fashioned as you might think. Art by Chaffee![[June 28, 1969] I Don’t Have Your Wagon (Review of “The Maltese Bippy”)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/The_Maltese_Bippy.jpg)

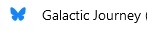

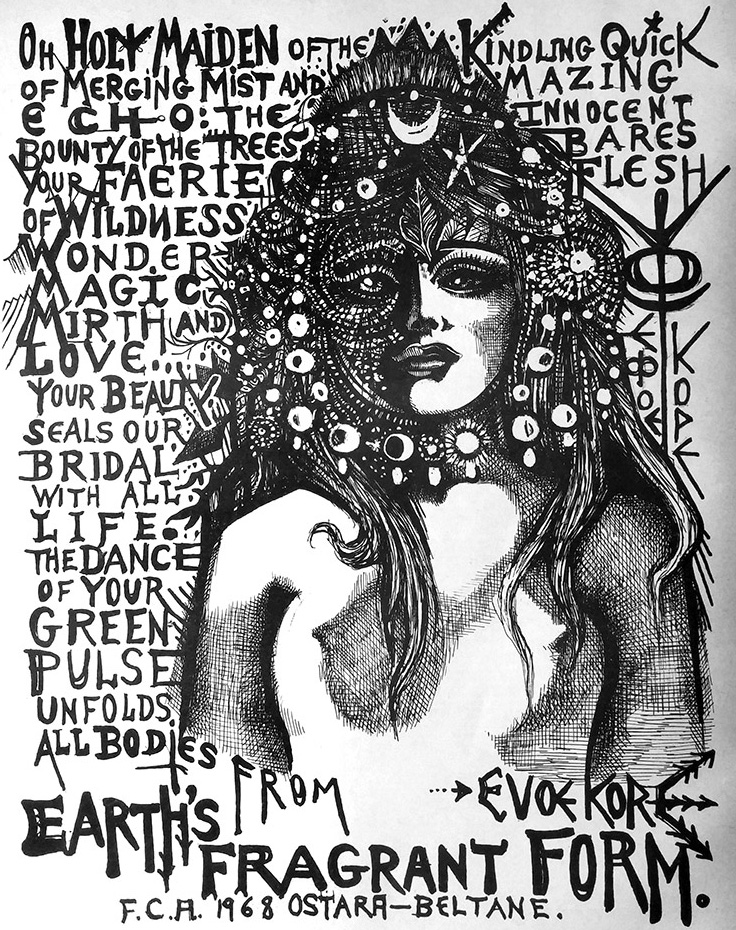

![[May 2, 1969] The Lusty Month of May: Beltane and Feraferia](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690502_Korythalia_issue2_pg8-672x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1968] What’s the Point? (August 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/IF-1968-08-Cover-505x372.jpg)

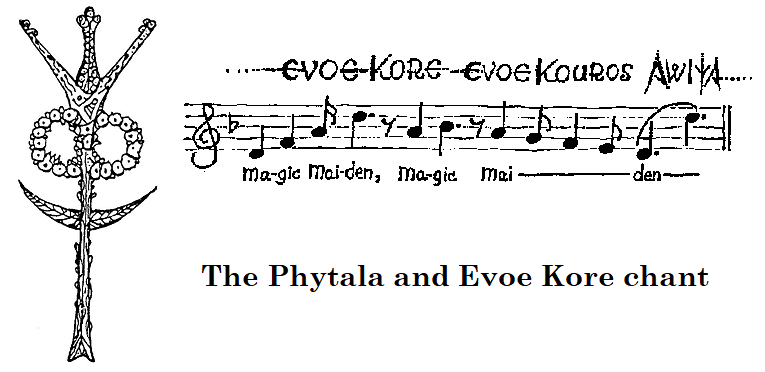

A political cartoon from after the First World War.

A political cartoon from after the First World War. Sam Nujoma (r.), President of SWAPO, shakes hands with Mostafa Rateb Abdel-Wahab, President of the Council for Namibia

Sam Nujoma (r.), President of SWAPO, shakes hands with Mostafa Rateb Abdel-Wahab, President of the Council for Namibia Supposedly for Rogue Star, which doesn’t have a starship crash. Or this many characters. Art by Chaffee

Supposedly for Rogue Star, which doesn’t have a starship crash. Or this many characters. Art by Chaffee![[April 10, 1968] Things Fall Apart (April 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/amz-0468-cover-447x372.png)

![[November 4, 1967] Conflicts (December 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/IF-1967-12-Cover-672x372.jpg)

Joan Baez is arrested in Oakland.

Joan Baez is arrested in Oakland. Fr. Berrigan pouring blood into a file drawer.

Fr. Berrigan pouring blood into a file drawer. Futuristic combat in The City of Yesterday. Art by Chaffee

Futuristic combat in The City of Yesterday. Art by Chaffee