by John Boston

Within Narrow Constraints

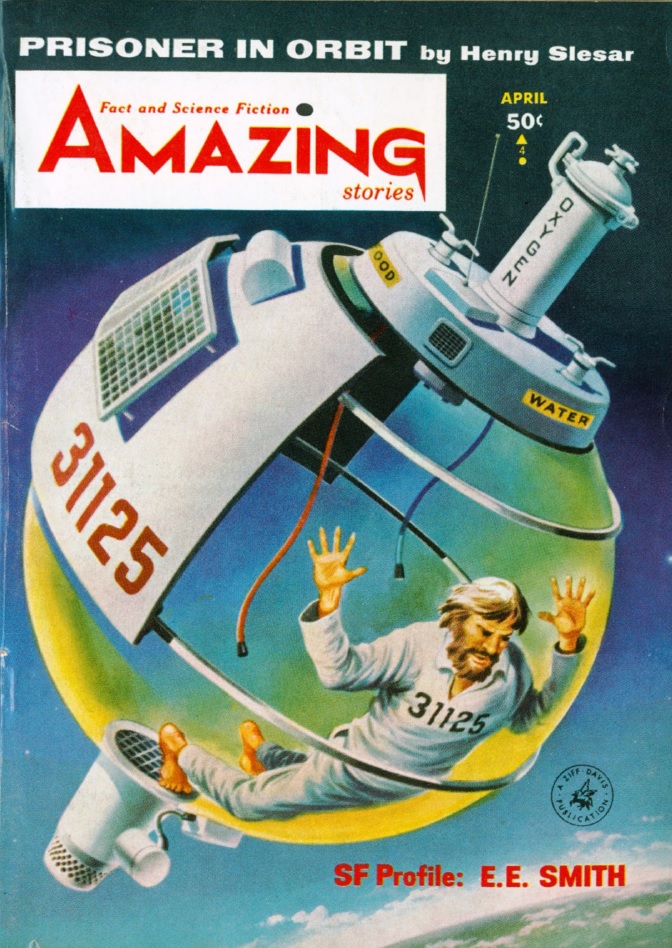

The April 1964 issue of Amazing features a story titled Prisoner in Orbit and a cover (by Alex Schomburg) depicting a guy in a transparent bubble, scarcely taller than he, looking out into space with a disgruntled expression. One might suspect that this depiction is overly literal, but no: it’s just what the author called for. Or, more likely, the story was written around the cover, an old magazine practice that has undoubtedly survived to the present.

Prisoner in Orbit, by Henry Slesar

The story is by Henry Slesar, a prolific contributor to Amazing in the late ‘50s and an occasional one since then, though that may be changing: he had a story in the last issue and has two in this one. Here, humans are fighting against the Maks, the android army of the Indasians, and the protagonist and his soldier buddies have been captured and sent to a prison asteroid, run entirely by the Maks. The story slips into the familiar groove of prisoner of war stories, with the captives scheming to escape and the Maks trying to keep them in line.

This old plot is made science-fictional by the rigid mechanical thinking of the Maks, who, after being informed that they really don’t need to kill prisoners who misbehave, since a little solitary confinement will do just as well, devise a confinement so solitary it drives the miscreants crazy. The cover thus justified, the story moves on to its real business: the war is over, won by the humans so conclusively that there’s no chain of command left to tell the authority-minded Maks to stand down and let the humans go. How to persuade them?

Clever solution, coming right up. Slesar has served a rigorous and prolific apprenticeship in Ellery Queen’s, Alfred Hitchcock’s, and other crime fiction magazines as well as in sf, and it shows. This is a highly professional if rather bloodless performance, with background deftly sketched in, the pace jazzed up with flashbacks and flash-forwards, in as smooth a style as you’ll find anywhere. Three stars for slick execution, even if there’s no reason to remember the story once you’re done.

The Chair, by O.H. Leslie

Slesar’s other story, The Chair, appears under his pseudonym O.H. Leslie, familiar from the Ziff-Davis magazines but even more so to the readers of Alfred Hitchcock’s. It is a bit livelier than Prisoner in Orbit but just as formulaic, splitting the difference between early Galaxy satire and the cautionary mode of, say, Richard Matheson or Charles Beaumont when they are not writing outright fantasy.

The eponymous Chair is an expensive commercial product that promises the ultimate in comfort and satisfaction of every need, at least if you get the extras like the Food-o-Mat and the Chem-o-Mat Plumbing Unit. You can see where that is going, and go it does, with the journalist protagonist chronicling the decline of his friend who gets a Chair, until the manufacturer figures out the perfect way to silence him. This one too is slickly executed, and enhanced by Slesar’s obvious familiarity with advertising style. Also there’s more of a point to it and you might remember it a little longer than Prisoner in Orbit. Three stars, a bit more lustrous than those for Prisoner.

The Other Inhabitant, by Edward W. Ludwig

Of course most of us presumably read sf for something other than slick execution. But we might miss it when it’s not there, as illustrated by this story, in which Astro-Lieutenant Sam Harding, exploring “Alpha III” (a planet of Alpha Centauri, apparently), discovers that he’s not alone; something is following him. As the story proceeds we learn that Lt. Harding’s situation is not quite what he thinks it is. This kind of psychological near-horror stands or falls on execution, and this one falls. In the hands of a more skilled writer it might have been quite effective. Two stars.

A Question of Theology, by George Whitley

A. Bertram Chandler, using his frequent pseudonym George Whitley for no apparent reason, contributes A Question of Theology, in which humans are about to land on a planet of Alpha Centauri (yes, that one again), which some time ago was visited by an unmanned vessel carrying experimental animals, and which now seems to have a well-developed civilization with cities. The humans’ reception is predictable to the reader if not to the characters. It’s perfectly readable—Chandler is no Slesar but he will serve for most purposes—but it reads as if the author wasn’t really very interested in it, and the theme is unfortunately reminiscent of some of his earlier, much better stories: the incisive The Cage, from Fantasy and Science Fiction seven or so years ago, and Giant Killer, the 1945 Astounding novella that made his reputation. Two stars.

Sunburst (Part 2 of 3), by Phyllis Gotlieb and The Saga of “Skylark” Smith, by Sam Moskowitz

The rest of the issue is taken up by the second installment of Phyllis Gotlieb’s serial Sunburst, to be reviewed next month, and another of Sam Moskowitz’s SF Profiles: The Saga of “Skylark” Smith. Edward E. Smith, Ph.D., is of course author of The Skylark of Space and numerous other grandiose space operas of bygone days done in a bygone style, and has failed to adapt to a more sophisticated genre and its audience, as Moskowitz essentially acknowledges. While some of the biographical detail is interesting, the point is otherwise elusive. Two stars.

Spectroscope

Last month, the editor proudly announced the advent of Lester del Rey as new proprietor of The Spectroscope, the book review column. This month, with no comment at all, del Rey is gone and the book reviewer is Robert Silverberg, who is knowledgeable and adept. Let’s hope he lasts more than a month.

Post-Mortem

So, the upshot: nothing terrible, which compared to recent performance is an improvement, but nothing especially interesting either, except possibly the serial installment. To be continued.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[March 13, 1964] NOTHING MUCH TO SAY (the April 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640313cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 11, 1964] Brought into Focus (<i>The Outer Limits</i>, Season 1, Episodes 21-24)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640311d-672x372.jpg)

![[March 9, 1964] Deviant from the Norm (April 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640309cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 5, 1964] Brushwinged, I Soar (Hannah Green's I Never Promised You a Rose Garden)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640305RoseGarden_Cover-383x372.png)

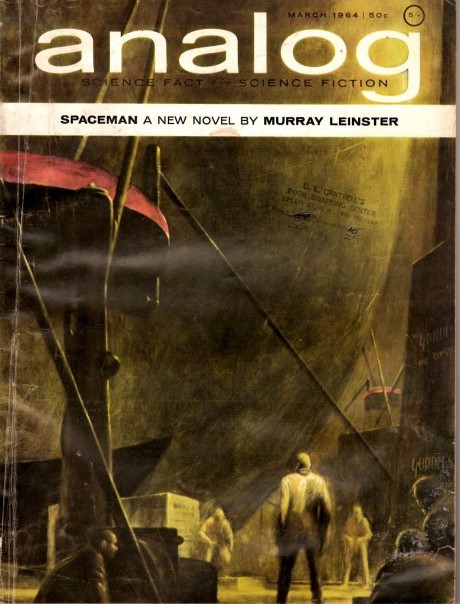

![[March 3, 1964] Out and about (March 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640303cover-460x372.jpg)

![[February 29, 1964] Think Twice — it's not all right (<i>The Twilight Zone</i>, Season 5, Episodes 17-20)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640229f-672x372.jpg)

![[February 27, 1964] Beatles, Boredom and Ballard ( <i>New Worlds, March 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640227cover-649x372.jpg)

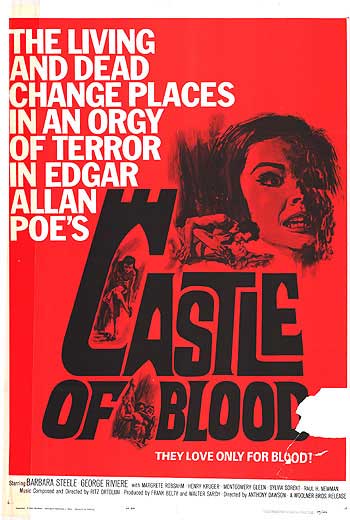

![[February 25, 1964] From the Sublime to the Ridiculous (<i>Castle of Blood</i> and <i>The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640225blood-350x372.jpg)

![[February 23, 1964] Songs of Innocence and of Experience (March 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640223cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 21, 1964] For the fans (March 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640219cover-665x372.jpg)