by Gideon Marcus

Star Trek offered a mirror to our present day world of Cold War tensions with its latest episode, "Errand of Mercy".

The episode begins with two mighty star nations, the United Federation of Planets ("a democracy") and the Klingon Empire ("brutal, savage") about to go to war. And not a border skirmish, but a full on, fleet vs. fleet conflict that may see one of the parties laid to heel.

In between them, strategically located, is the planet of Organia. Its inhabitants are humanoid, seemingly primitive. As chance would have it, the Enterprise gets there before the Klingons, and Kirk (accompanied by Spock) attempts to persuade the Organians to accept a Federation protectorate, in exchange for defense, technology, education, and other benefits of enlightened society.

The Organians rebuff a bemused Kirk, assuring him that there is no danger. Whereupon the Klingons arrive, quickly establishing a military governorship. Unable to convince the Organians to fight for their freedom, Kirk and Spock attempt a two-man resistance effort. They are quickly sold out by the Organians, but then rescued from prison by the self-same natives. The Klingon Commander, Kor, orders the slaughter of 200 Organians every hour until they are returned. Again, the Organians assure our heroes that nothing amiss is occurring.

Ultimately, two mighty battle fleets square off in the vicinity of Organia. This proves to be the last straw. The people of Organia demonstrate heretofore unseen power, their spokesman, Ayelborne, appearing in person on the Klingon and Federation homeworlds, announcing the immobilization of all combatants.

The Organians reveal their true power

In a nice moment, Kirk and Kor express their outrage at not being allowed to settle their differences through war. They quickly come around when it is clear they have no choice. In the final act, Kirk broods over his belligerence, feeling much chagrined. Spock explains that they have many millennia to go before they, too, can become Gods.

We've seen many episodes where the Enterprise meets much more advanced races: "Charlie X", The Squire of Gothos", "The Corbomite Maneuver", "Arena", "Shore Leave". Some might even be tired of the theme (I am not–we should expect half of the beings we encounter to be far beyond us; cosmic timescales favor this). But "Errand of Mercy" is the best of this type of show we've seen so far, illuminating our frailties as a species beautifully.

"Errand" is aided by some of the best casting we've seen in the show. John Abbott imbues Ayelborne with dignity and strength, suffused with a penetrating mildness. And John Colicos, who I've seen before on Mission: Impossible, is affably delightful as Commander Kor. By turns irritated and almost entreating, Kor comes across as, if anything, a lonely man. He is isolated by his rank, by his position as an obvious intellectual and aesthete in an Empire of thugs. Kor seems to want nothing more than to have a friend, and the only person who might qualify is his mortal enemy, Captain Kirk. To echo Mr. Spock, "fascinating."

I appreciated the justifications for war laid out by both sides, as they appealed to Ayleborne to allow them to continue their fight. The Klingons, Kirk says, raided planets. The Federation, Kor insists, was hemming the Klingons in, cutting them off from territory that had always been theirs. Yes, the American/Soviet parallels are strong (to the point that Kor boasts that the Klingons will win due to their unswerving dedication to their state, and their positions as cogs in its system). Juanita Coulson, in the latest Yandro, praised the show for its economy of writing, how much they pack into almost throwaway lines. This episode does a lot with a little. In this, they are aided by director John Newland, who did most of this year's excellent (but abortive) spy show, The Man Who Never Was.

And Sulu took the center seat again!

There were some complaints voiced about the show during our viewing. Two observed that Kirk was too quick to take the Organians at face value, asking the wrong questions (when he asked any) as to why they felt so secure. To that, I note that 1) Kirk is, as he says in the episode, "a soldier, not a diplomat"; his behavior is entirely consistent with what we've seen in prior episodes (viz. "The Squire of Gothos" and "Arena"). 2) A war had just been declared, with shots already fired. Kirk's focus was, shall we say, narrow. This also may explain why Spock was unusually accommodating in his impromptu guerrilla role.

Indeed, that's what I love about this episode. The Organians put themselves into a form humans can understand, and yet it's still not enough. Both Kirk and Kor (an intentional similarity of names?) are irritated with these beings who do not behave as they "should". The only beings with whom they share any common ground are each other!

"In another life, I could have called you 'friend'. Wait. Wrong episode.

Another viewer noted that the Federation, as American analogs, would have simply taken Organia, as the Klingons ultimately did (or tried). And perhaps they would have. I like to think the humans (and Vulcans) are better than that. At the very least, Kirk tried to persuade them peacefully. But given the deliberate portrayal of the Klingons as the Federation through a glass darkly, I think the viewer may have had a point. And probably one intended to be gotten by the writer.

Speaking of which, Gene L. Coon is a name that has popped up several times recently. Between writers Coon and D.C. (Dorothy) Fontana, it does seem that Star Trek is reaching a consistent maturity. Gone are references to "Earth" (though the "Federation" has a single homeworld, per Ayelborne the Organian). The show seems to have settled on "Vulcan" over "Vulcanian". The characters are firmly established.

With the arrival of the Organians, one wonders if the character of the show will change drastically. Are the Organians a galactic phenomenon, or do they only care about their sector of space? That they didn't intervene in the war with the Romulans suggests the latter. If the Organians are strictly local, will the Federation and Klingons find other frontiers to fight about?

I can't wait to find out! Five stars.

A Peaceful Fantasy

by Jessica Dickinson Goodman

I've written before about alien cultures reacting to Federation colonialism – from the Horta last week to the Gorn a few weeks before. In this episode, we got to see what Captain Kirk hoped was the beginning of if not colonization, then as Gideon puts it, "protectorate status."

And we saw the Organians gently reject this and all such overtures. Over and over again, we hear varions of of, "Captain, I can see that you do not understand us. Perhaps…" and "We are in no danger."

"Mellow out, man. Everything's cool!"

At first, like Captain Kirk, I thought the Organians unbearably naive. But it turns out that Captain Kirk, and I, were arrogant. They were in no danger; capable of unilaterally ending a war that promised galaxy-wide devastation with a thought. They were ably prepared to defend themselves and the two societies who so wished to do violence around them.

Of all of the god-like aliens we have seen, I liked these the best. No capricious squires or whiny, cruel children; the Organians had a philosophy, the discipline to live by it, and the power to ensure they remained unbothered by outside forces while on their paths. I can imagine the Horta or the Gorn would have envied those powers, though as Commander Spock pointed out, "it took millions of years for the Organians to evolve into what they are. Even the gods did not spring into being overnight."

Spock comforts Jim for being a primitive.

I find these forms of power fantasies deeply satisfying. Every day, we see the power of violence, of guns, of bombs, of war. To see, if only for a few, technicolor minutes, a power to stop war? To prevent violence? To ensure cultural continuity and security in the face of attempts to colonize? That is a fantasy I enjoy a great deal. Lest I sound too star-struck, I will note that I would have preferred to see any Organian women, any evidence of many cultures mixing together, of creativity, of growth, rather than the mild stasis that seemed to characterize their society. But for what it was, it was good to see.

Just don't ask me to live there.

Four stars.

An Actually Superior Superiority

by Elijah Sauder

In this episode of Star Trek, we saw not just the most powerful god-like-beings we have seen, but also the most compelling. In our previous encounters, the god-like-beings' powers were potent, but only in a localized region of space. In this episode the Organians immobilized the entire Space Force and Klingon Empire’s armies. To quote (approximately) Kirk, “We never had a chance; the Organians raided the game.”

"Mooom! He started it!"

As humans we want to feel in control and to exert such control through whatever means necessary; we meddle, we fight. But the Organians did not exhibit the same behavior. They expressed disgust at the thought of meddling, and when they meddled, it was in the most pacifist of ways. This gave them a suggestion of superiority far greater than that of the previous powerful beings, who flaunted their power in a way that was nothing more than human.

I very much enjoyed this episode through and through–not just as a show, but as a writer’s vision of what we should strive to be. Looking around at the violence and overreach of global superpowers we see today, what would it look like if we could transcend our primal nature to something better?

I give this episode 5/5.

The Dittoverse

by Lorelei Marcus

A crucial part of the science fiction genre is aliens, and Star Trek gives them to us in great variety. We have the completely unfamiliar aliens like the salt-monster from "The Man Trap" or the silicon-based carpet monster from "The Devil in the Dark". Then there's the God-like beings, which display evolution well beyond the people of the Enterprise. My favorite aliens, though, are the humanoid ones, because their existence suggests a great deal about the Star Trek universe.

The Klingons are the third race of aliens we've seen that seem to be technologically and evolutionarily similar to the humans of the Federation. First were the Vulcan(ians), and then the Romulans, though there is strong evidence that the Romulans are distant relatives of the Vulcans, and thus constitute one species. The Klingons seem to have a similar relationship to humans based on their appearance, customs, and technology. Perhaps the Klingon Empire is the result of a colony ship like Khan's, launched during Earth's warring period. Yet I suggest there is a larger mystery afoot.

Minor differences aside, there is also a distinct resemblance between humans and Vulcans [and apparently an ability to interbreed (ed.)]. Initially, one could attribute this to the limitations of Star Trek's make-up department, but I propose there is an explanation for not just the connection between humans and Vulcans, but every humanoid alien seen and to be seen on the show.

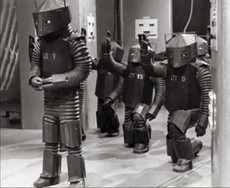

Amazing fashion sense aside, the Klingons are remarkably humanoid.

This answer lies in "Miri" (the episode, not the character). "Miri" introduces that 'mirror Earths' exist, worlds that appear exactly like the Federation's homeworld, yet with distinct populations and even timelines. While we've yet to see another identical Earth like the one in "Miri", we have seen many habitable worlds and humanoid aliens. What if a common ancestor of the humans, the Klingons, the Vulcans, all started from the same place, on the same world, at a certain early point in its evolution? Then, this proto-Earth was progressed countless times in separate timelines, each evolving into the cultures and creatures we know. Each of these separate Earths were somehow folded into one space, perhaps with some space-time affecting technology like a Starship's warp drive. We already know time travel is possible using the Enterprise. Why not an accidental collapse of the fourth dimension as well?

There is a simpler solution, of course. All of these identical worlds could be deliberate constructs for some higher being's experiment. Personally, I think this explanation is less interesting, but with the number of God-like aliens we've seen, probably the more likely.

Either way, I love science fiction that makes me speculate on the very fabric of the universe. This episode is definitely a great additional piece to the puzzle that is Star Trek.

Four stars.

I have no idea what to make of this next episode of Star Trek. Come join us tonight at 8:30 PM (Eastern and Pacific) and help us figure it out.

Here's the invitation!

![[March 30, 1967] The Peacekeepers (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Errand of Mercy")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670330title-672x372.jpg)

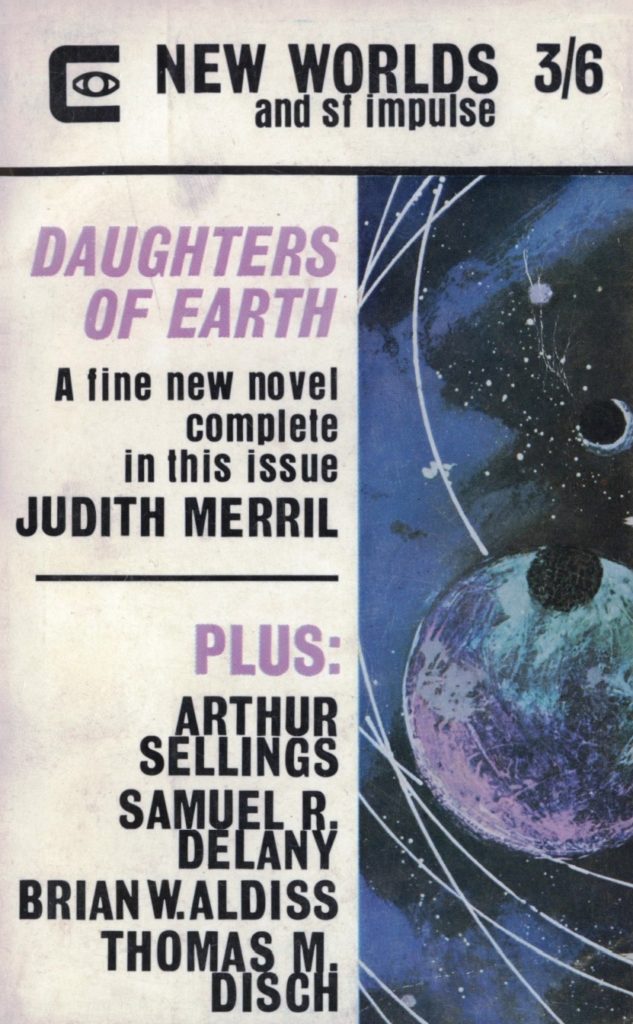

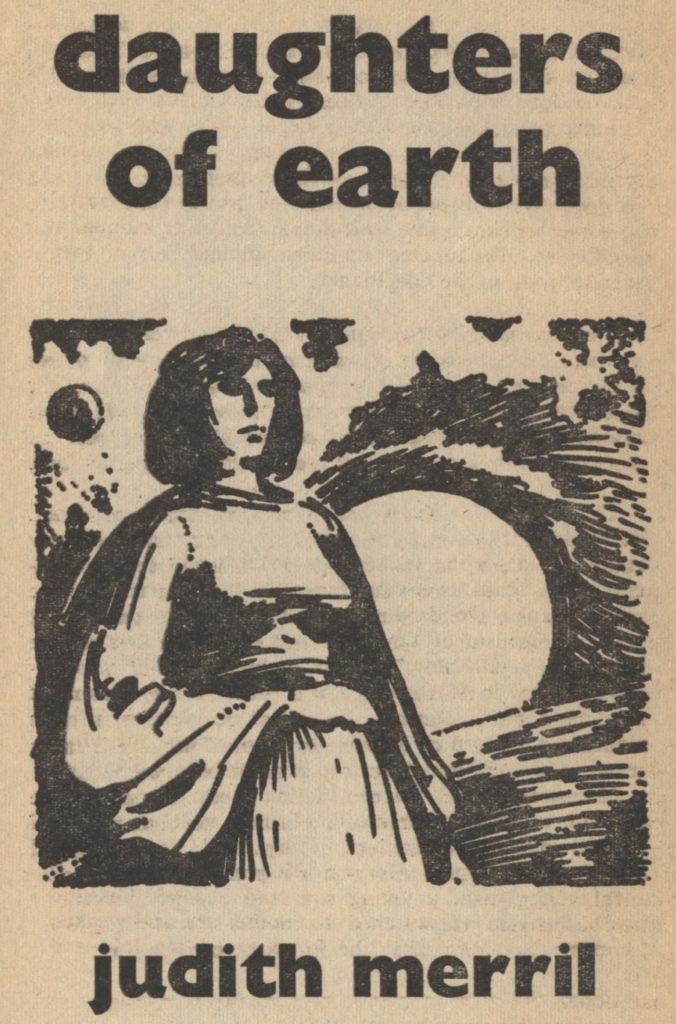

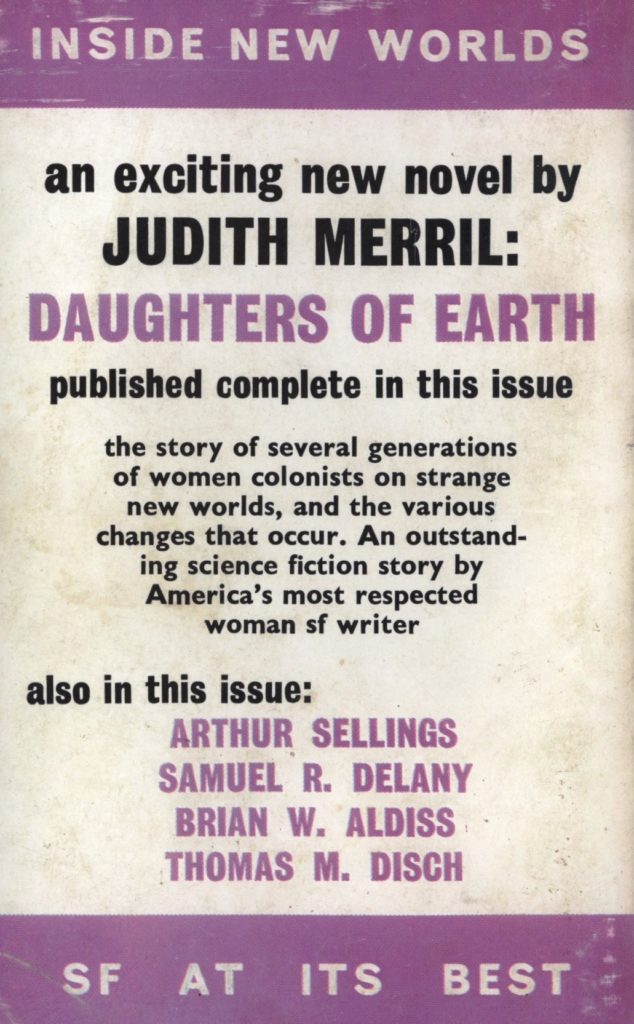

![[March 26, 1967] Changes Coming <i>New Worlds and SF Impulse</i>, April 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/New-Worlds-April-1967-672x372.jpg)

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

![[March 22, 1967] The Lurking Fear (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Devil in the Dark")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670322title-672x372.jpg)

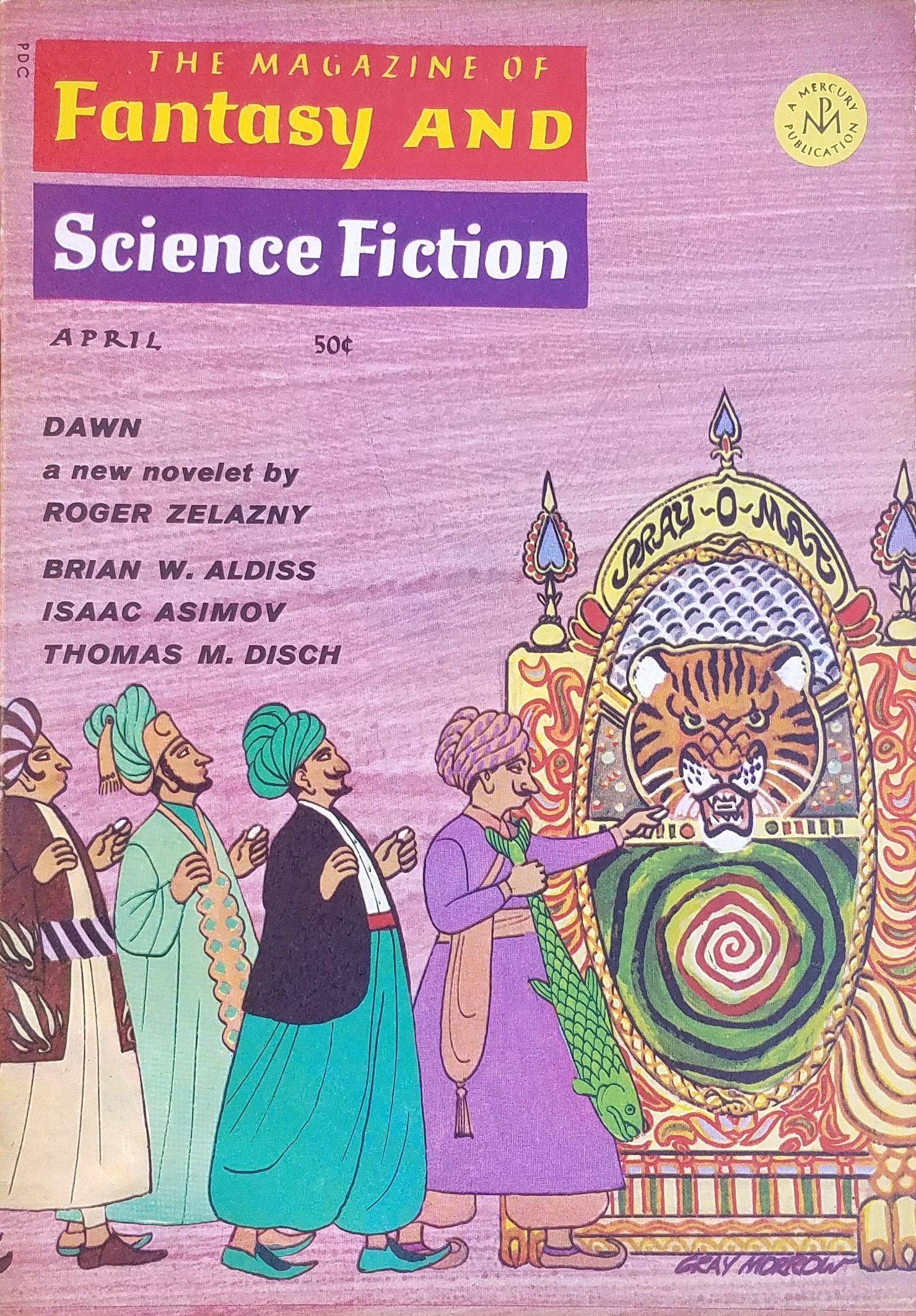

![[March 20, 1967] Vistas near and far (April 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670320cover-672x372.jpg)

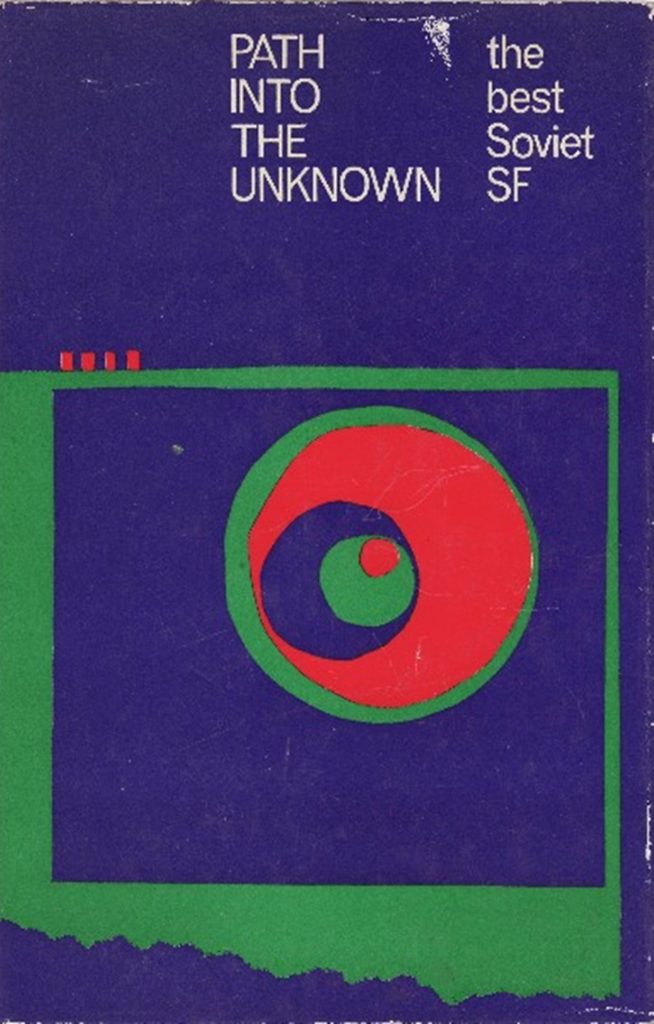

![[March 18, 1967] From Both Sides of the Curtain (<i>New Writings in S-F 10</i> & <i>Path into the Unknown</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Banner-672x372.jpg)

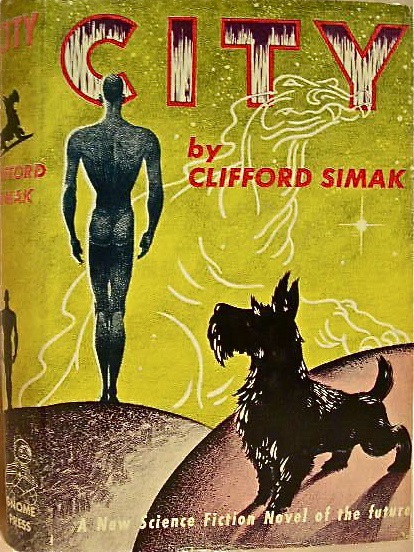

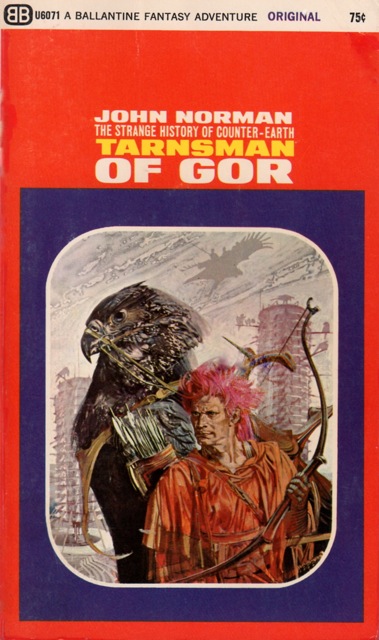

![[March 16, 1967] A Matter of Life and Death (<i>Why Call Them Back From Heaven?</i> by Clifford D. Simak; <i>Tarnsman of Gor</i>, by John Norman)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670316covers-672x372.jpg)

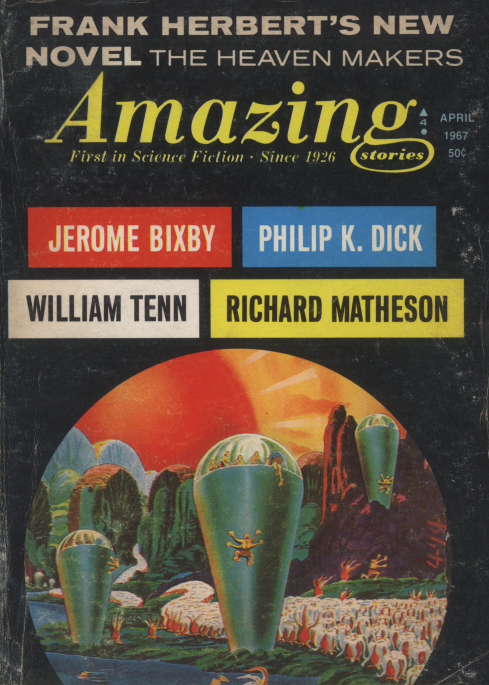

![[March 14, 1967] Family Matters (April 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/amazing-apr-1967-cover-489x372.png)

![[March 12, 1967] Computerized Futures & Humanity (Out of the Unknown: Season Two)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Out-of-the-Unknown-2.jpg)

![[March 10, 1967] Mediocrités, Slayer of Magazines (April 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670310cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 8, 1967] Absolute perfection (<i>Star Trek</i>: "This Side of Paradise")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670308title-672x372.jpg)