Each month, I lament what's become of the magazine that John Campbell built. Analog's slow decline has been marked by the editor's increased erratic and pseudo-scientific boosting behavior. Well, I just don't have the heart to kick a dog today, and besides, the fiction is pretty good in this month's (November 1960) issue. So let's get right to it, shall we?

"Mark Phillips" (Randall Garrett and Laurence M. Janifer) have a new four-part serial in their Malone series. Set in the 1970s, the series details the adventures of a couple of federal agents, who are helped in their cases by a telepath who believes herself (and may actually be) Queen Elizabeth I. I won't spoil the details of this one, Occasion for Disaster, but I've liked the previous novels, so I suspect Occasion will also be pleasant reading.

Heading off the magazine's short stories is a fun piece by Theodore L. Thomas, half of the pseudonymous duo that previously brought us a fascinating study into the world of copyright, The Professional Touch. Crackpot continues in that vein, featuring a brilliant old scientist (Prof. Singlestone… get it?!) who convinces the world that he's gone senile. His aim? To make his work so disreputable that no government agency will want it, so that no university will employ him, so that he can for the first time in his life enjoy working as a truly free agent. So that when his invention proves to be utterly unignorable, he will be the master of its fate. Cute stuff. Three stars.

Next up is E.C. Tubb's The Piebald Horse. It starts out well enough with a Terran spy trying to escape a repressive alien world with his brain full of sensitive knowledge. The jig seems up for him when the aliens employ telepaths as mind-screen agents, but they are foiled when the protagonist pickles himself continuously until he can depart the planet. I'm pretty sure I just saw this tactic in Fred Pohl's Drunkard's Walk. 2 stars.

These two stories are followed by a pair of execrable "non-fiction" articles. Captain, MSC, US Navy H.C. Dudley, PhD (he must be authoritative–look at all the titles!) has the first: The Electric Field Rocket. He maintains that the Earth's electrostatic field can be used to assist rocket launches; he implies that the Soviet's lead in the Space Race is attributable to their taking advantage of said phenomenon. Not only is the article unreadable, but I suspect the science is bunk. Time will tell. 1 star.

Speaking of which, Editor Campbell contributes the second article: Instrumentation for the Dean Drive. I'm not even going to dignify with a review this next piece in an endless series on Dean's magical inertialess engine. He needs to knock it off already. 1 star.

Blessedly, the rest of the issue is quite good. The reliable Hal Clement is back with Sunspot, an exciting, if highly technical, account of a group of spacemen who ride a comet around the Sun. What better shielding exists for a close encounter with a star than billions of cubic tons of ice? Four stars.

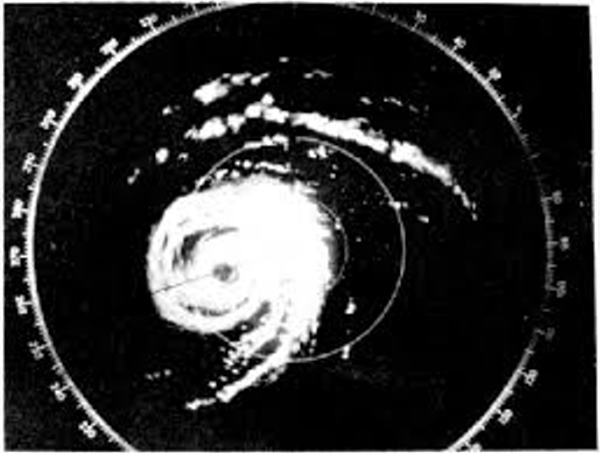

At last, we come to H. Beam Piper's Oomphel in the Sky. The set-up is great: a Terran colony world in a binary star system courts disaster when the planet makes a close approach to the usually far-away sun. This triggers unrest amongst the natives, threatening Terran and native interests alike. I'm an unabashed fan of Piper, and this is a good tale, although he does get a little patronizing toward the do-gooder but ineffective Terran government. I like the strong anthropological bent, and I appreciate the respect with which he treats the natives and their interests. Four stars.

In sum, the November 1960 Analog (I almost typed "Astounding") is quite decent, fiction-wise. Campbell needs to do what Galaxy's Gold has done and hire a ghost editor, and a real non-fiction author. I can't believe there isn't another budding Asimov or Ley out there champing at the bit to be published…

The fourth and last Kennedy/Nixon debate is tomorrow night! I hope you'll all watch it with me, but if you can't bring yourself to sit through another hour of sparring, I'll give you the full details the following day.