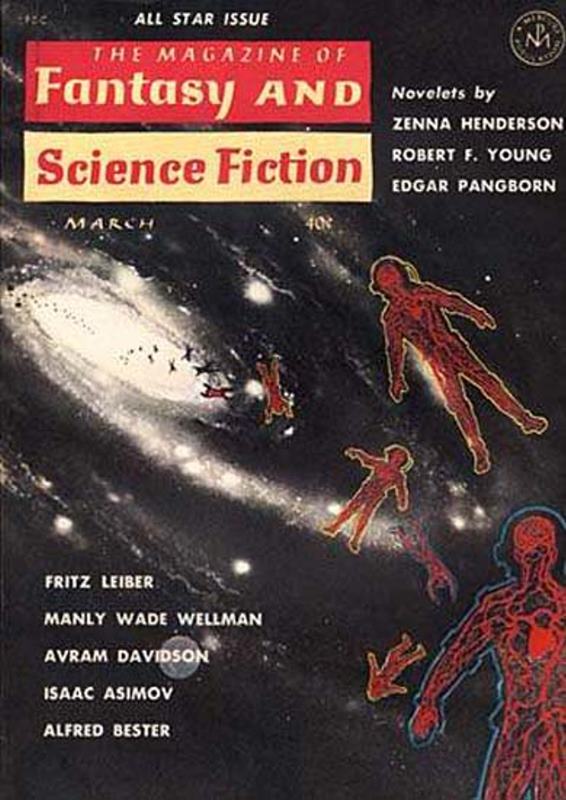

[Apr. 7, 1962] Half and Half (The Twilight Zone, Season 3, Episodes 25-28)

by Gideon Marcus

I have criticized the show that Rod built over the course of this, the third season. Serling has seemed tired, borrowing cliches from himself. Thus, I was delightedly surprised to find some of the best quality of the series appearing more than half-way through this latest stretch. Read all the way through because, in keeping with the show, there's a bit of a twist around the mid-article mark. You won't want to miss it:

The Fugitive, by Charles Beaumont

A 12-year old girl with a bum leg has befriended a sweet old man with magical powers. But he's on the lam from another world. Can the plucky child save him?

There's a lot going on for this episode: genuinely likable characters, several plot twists, fast pacing. It's a charming piece with a strong young woman in the lead role. We need more like this one. Five stars.

Little Girl Lost, by Richard Matheson

Mom and Dad are wakened by the cries of their young daughter, but when they rush to her aid, she is nowhere to be seen. Where could she be trapped such that she could be so close yet so far away?

This one packs a punch to any parent. Richard Matheson has a knack for turning in compelling screenplays, and Lost was apparently inspired by a personal experience. You'll be on the edge of your seat all the way to the exciting resolution. Five stars.

Person or Persons Unknown, by Charles Beaumont

Unfortunately, the winning streak doesn't last. With Persons, we're back to vintage 3rd Season. A fellow wakes up to find all evidence of his existence had disappeared. His wife and co-workers don't remember him. His wallet is empty of identification. He slowly goes mad, in typical Twilight Zone fashion and ends up in an institution. There's a twist at the end, but it's not much of a surprise.

What kills this episode is that there is five minutes of content stretched out into a twenty-two minute show. A far more interesting piece might have been made of him finding out that he was slipping across universes. There would have been time to throw him into a few different situations and still leave space for an interesting resolution. Instead, we get this dull story. Two stars.

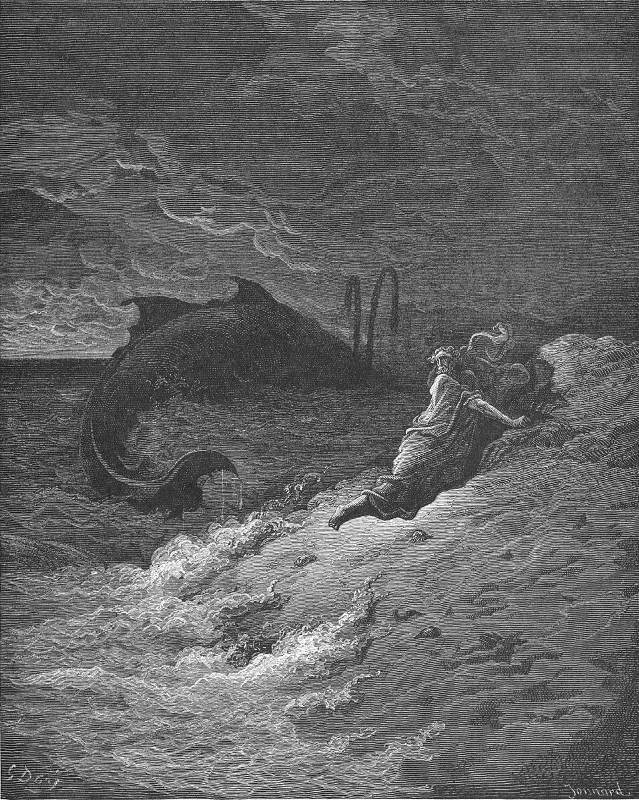

The Little People, by Rod Serling

Here's an episode that starts poorly and doesn't travel far from there. Two humans crash land on an alien world (an "asteroid," per Mr. Sterling's preview last week…but clearly a planet, even though it's only "millions of miles" away). The junior of the crew has delusions of godhood, which are nicely fulfilled when he finds an entire city of tiny humanoids, over which he cruelly lords. His fun is put to a quick end when another pair of spacemen, these hundreds of times larger, land and squash him like a bug.

It's a dumb tale, and Serling has apparently never heard of surface tension or the square cube law. I did, however, appreciate the implied critique of our religions. After all, does not the Judaeo-Christian-Moslem tradition feature an almighty and oft-times menacing God? One who would deluge a planet or decimate a people out of spite? Maybe that's the semi-precious stone at the heart of a drab pebble of a piece. Two stars.

***

Now, where's the Young Traveler, you ask? Here she is, taking on the month's episodes in reverse order, so that unlike the viewing audience, you can end on a positive note.

***

by Lorelei Marcus

“I’m hoping we’ll have a more reliable batch of good episodes in the future, but you never know. I’m counting on you Serling!” (me, last article)

Well, I think I can safely say that Serling did come through, for the first two episodes at least. This is a special day, because something that has never happened before, has happened. However I'm not going to tell you what it is until later. This review will be a little bit odd, in that I'm going to review the episodes in reverse order of how we actually watched them. My father reviewed them in the right order of their airing, so you shouldn't get confused. So without further ado, I bring you “The Little People”

The Little People, by Rod Serling

The episode stays true to its title well, being about a whole city of microscopic alien people. Unfortunately, that's all the episode is. Two spacemen crash onto a rocky planet (of course the planet has the same atmosphere and gravity as Earth) and are stranded until they can fix their ship. One of the two men happens to stumble on a tiny city, almost too small to see. The man becomes power hungry and stays on the planet, even after his fellow spaceman repairs the spaceship and flies away, so he can rule the tiny people as their “god.” It ends with two real giants coming and accidentally killing the spaceman, saving the tiny people.

I think my biggest peeve with this episode is the fact that the whole focus is on these tiny people and their town, and yet we only get about three shots of it. I understand these effects are difficult to create, but it felt so lazy having almost all the shots be composed of just one of the two men's faces. I would have loved to have seen some small people or maybe even a model home or two rather than the boring cinematography we actually got. I give this episode 1.5 stars. The story was bland and predictable, the camera-work was boring, and the set was boring. The only thing I liked was the acting! Definitely not one of Serling's best.

Person or Persons Unknown, by Charles Beaumont

Sadly, Serling did not come through for us in this next episode either. This episode can be summarized in one sentence: Man loses identity. It's as interesting and ground breaking as it sounds. Normally I would summarize the episode here, but there is literally nothing else to summarize: that one sentence was the episode.

However, despite being the utter mediocre piece of work it was, it did give me something worth while. In the beginning of the episode a man – the one who loses his identity – wakes up next to his lovely wife. He is a total jerk to her as he gets up and changes, commanding her for breakfast. It was then that I realized how much I really wanted to see an episode about a husband and wife switching places.

Just imagine, there could be humor, for example, the man being unable to cook eggs, and the woman unable to tie a tie. However, there could be so many deeper messages in the episode too – who's “in charge” of the house anymore? Who will actually go to work? Not only that, but I think it would be the perfect kind of confusing, interesting, thought-provoking episode that Serling wants to make.

Unfortunately we didn't get that episode, we got this one, and I give it 2 stars. It really felt like a bad season one episode, being entirely mediocre and dragged out. Could there still be hope for The Twilight Zone at this rate?

Little Girl Lost, by Richard Matheson

The episode started with a mother and father waking up to their child crying. The way it was acted out felt very real to both my father and me, since we'd both experienced the event from opposite perspectives. Anyway, when the man goes to his daughter's room he can hear her crying, but he can't see her! He wakes his wife in a panic as their dog frantically barks outside. Now, I'm going to stop the summary right there, because I want to force you to watch the episode yourself. It's just that good. Great special effects, superb acting, amazing story telling, and overall a perfect episode. 5 stars, in fact, the first 5 star rating I've given anything we've watched since my dad started this column!

The Fugitive, by Charles Beaumont

This last episode starts out with a group of kids playing with an old man. Out of these kids, one of them in particular stands out. A feisty little girl in boy's clothes and a leg brace. She connects most with the man, and its clear that they are close in a cute, grandpa-grandchild sort of way. I'm sorry to do this to you again, but I'm afraid I'm going to have to cut the summary short again to avoid spoiling anything else about the episode.

This episode is my favorite episode of Twilight Zone, and really my favorite thing we've watched since the beginning of the Journey, by far. Now I can hear you confusedly saying to yourself, “wait wasn't that last episode five stars?” I reply with yes, and so is this one. It would get more than the last, excellent episode, but the meter stops at 5. The only flaw with this story was there wasn't enough of it. It has everything I like in The Twilight Zone and nothing I don't. No people going crazy, no padding, no lackluster twists, nothing creepy – just a fantastic situation and characters you care about. I want you to go watch it right now, well maybe after you finish reading this article, that is.

***

In sum, that truly was a legendary combo with two 5 star episodes in a row. I did the reviews in reverse so I could save the best for last. I hope you will go watch those two episodes and enjoy them as much as I did. And now, I think all that's left to say is:

This is the Young Traveler, signing off.