by Victoria Silverwolf

Our esteemed host has already provided many detailed analyses of 1962's science fiction films, as well as others tangentially related to SF (including one which also features the pretty actress pictured above, Ms. Barbara Eden.) But missing from the Traveler's roster of reviews has been a focus on the related genres, the fantastic and the horrorful. With that in mind, I 'd like to fill this gap with brief reviews of last year's pictures with more supernatural themes, as well as a few others which may not technically be fantasy, but which have the same feeling.

(Perhaps I am in a retrospective and nostalgic mood because of the heavy storm that struck part of the United States on New Year's Eve. Even in my neck of the woods, in the southeastern corner of Tennessee, an appreciable amount of snow fell, swaddling us in a cozy quiet blanket. Shown here are playful students at the University of the South, not far from where I live.)

So enjoy a mug of steaming hot chocolate and sit near the fire as we talk about the magical movies of last year.

Fantasy Films of 1962

Though nothing released last year captured the sheer wonder of 1959's The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, nevertheless, that excellent movie did inspire a handful of similar films, albeit without the special touch of Ray Harryhausen's stunning visual effects. Before I consider these pale imitations, allow me to dismiss a pair of silly comedies.

The title of Moon Pilot (based on Robert Buckner's novel Starfire, discussed here a while ago) suggests a serious tale of the near future, but the plot of this lighthearted farce is pure space fantasy. An astronaut (Tom Tryon, seen in the surprisingly good SF movie I Married a Monster from Outer Space) is scheduled to leave Earth on a secret flight to the Moon. He meets a mysterious woman (French actress Dany Saval) who warns him not to go into space. She's actually an alien from the planet (sic!) Beta Lyrae. Hijinks and romance ensue. Although the leads are attractive, the comedy is very broad. Kids may get a kick out of the antics of the movie's chimpanzee co-star. Two stars.

Our two star-crossed lovers bursting into song.

***

Equally goofy is Zotz!, based on a novel of the same name by Walter Karig. Tom Poston stars as professor who obtains an ancient amulet with mystical powers, leading to slapstick complications. Surprisingly, the screenplay is by Ray Russell, who wrote the brilliant Gothic chiller Sardonicus, published in Playboy in 1961 and quickly adapted into the pretty good horror movie Mr. Sardonicus, directed by William Castle, who also gave us the far inferior Zotz!. We'll meet again with Mister Russell a little later in this essay, with something more appropriate. Two stars.

The enchanted amulet that leads to so much mischief.

***

Turning from wacky antics to swashbuckling adventures, we have a trio of movies, ranging from expensive spectacles to low budget quickies. The degree of entertainment supplied is not necessarily proportional to the amount of money spent.

Filmed in Cinerama, The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm uses the talents of George Pal, which made The Time Machine such a delight, to bring three fairy tales collected by the pioneering folklorists to life.

In The Dancing Princess, a humble woodsman (Russ Tamblyn) discovers that a beautiful princess (Yvette Mimieux, also of The Time Machine) secretly goes out at night to dance wildly with gypsies.

Looks more exciting than sitting around the palace.

The Cobbler and the Elves features puppets in the familiar story of the shoemaker's helpers.

George Pal displaying his experience with Puppetoons.

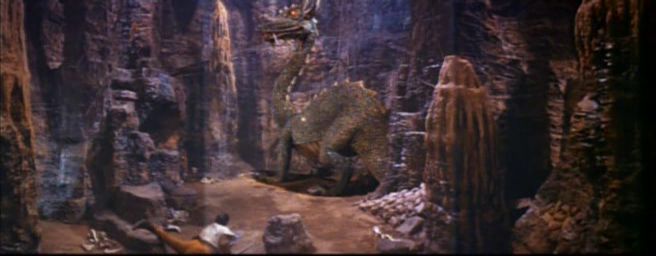

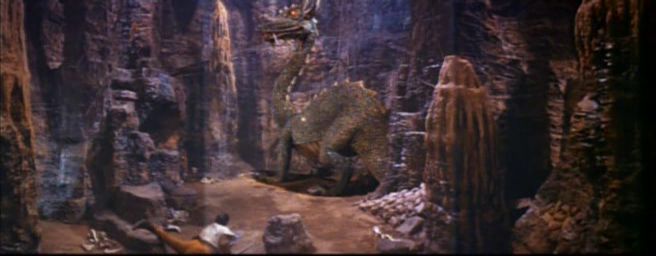

The most elaborate special effects are reserved for The Singing Bone, which includes a battle with a dragon, as well as a rather grim (pun intended) tale of murder and a message from beyond the grave.

Impressive cave, goofy dragon.

Unfortunately, these enjoyable sequences alternate with dull sequences set in the real world. Barbara Eden plays the love interest of one of the Grimms (hence her appearance at the start of this article.) Two stars.

***

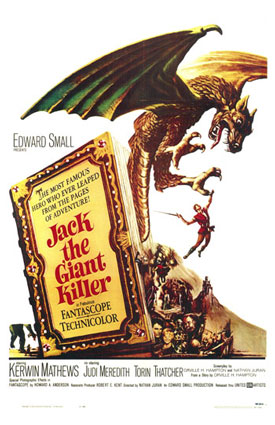

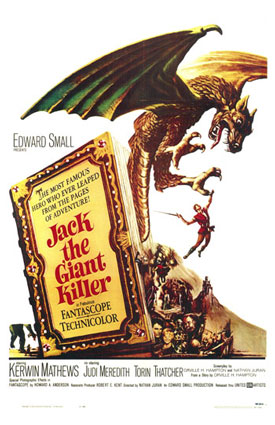

More modestly funded was Jack the Giant Killer, clearly intended to remind audiences of The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. Both films star Kerwin Mathews as the hero and Torin Thatcher as the villain. They even have the same director, Nathan Juran. Too bad they couldn't get Ray Harryhausen for the special effects. His replacements do a decent job, but they can't quite capture the same magic. Still, the movie is reasonably entertaining.

Pretty cool two-headed giant, not-so-cool sea monster.

No reason to go into details about the plot. The Good Guy battles the Bad Guy's monsters, winning the hand of the Princess. Three stars.

***

An even lower budget brought moviegoers The Magic Sword. Bert I. Gordon, who created abysmal science fiction movies of the Big Bug variety, including Beginning of the End and The Spider, adds a sense of humor to the story. Our hero is George, the adopted son of an elderly sorceress. With the help of the title weapon and six knights brought out of suspended animation, he rescues yet another beautiful princess from yet another evil wizard (the great Basil Rathbone.)

Don't hurt yourself with that thing.

The special effects are shoddy, but the sorceress and her two-headed servant are amusing. Three stars.

Too many heads spoil the broth.

Horror Films of 1962

Movies dealing with the darker side of the fantastic ranged from abysmal to excellent. Let's look at the ridiculous before we talk about the sublime.

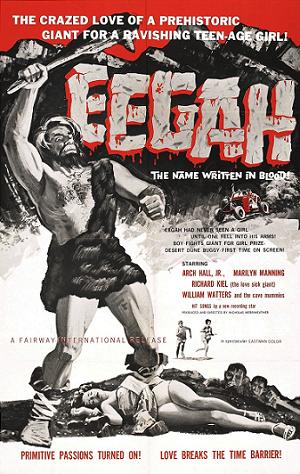

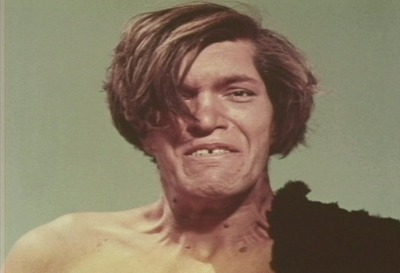

You're more likely to scream with laughter than fear while watching Eegah, an absurd tale of a giant caveman vaguely terrorizing some young folks. Arch Hall (senior) directs Arch Hall (junior) as the hero, making this more of a home movie than a feature film. One star.

The monster and hero; can you tell who is who?

***

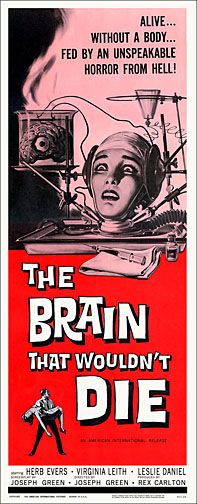

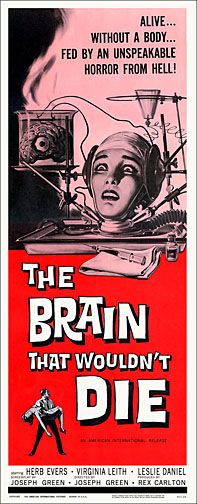

Equally inept, but a lot less innocent, is the gruesome shocker The Brain That Wouldn't Die. A mad scientist keeps the head of his girlfriend alive after she is decapitated in a car accident. He then hangs around figure models, searching for the perfect body to transplant onto what's left of her. There's also a monster locked up in his laboratory, which is responsible for a particularly bloody scene near the end. One star.

I hope her nose doesn't itch.

***

On a more professional level, two studios released movies that were mediocre variations on what had come before.

In the United States, Roger Corman offered his third Poe adaptation, The Premature Burial. Loosely adapted by Charles Beaumont and Ray Russell, the story features a man with a morbid fear of being buried alive. He builds an elaborate system of devices in his mausoleum, in order to make his escape if this happens. Things don't go well. Ray Milland replaces Vincent Price, so memorable in House of Usher and The Pit and the Pendulum, in the lead role. It's a fairly dull affair, although nicely filmed and with an unexpected twist ending. Two stars.

Part of Milland's tool kit.

Meanwhile, the British studio Hammer, which had so much success bringing Dracula, Frankenstein's Monster, Jekyll and Hyde, the Mummy, and a Werewolf back to the silver screen, revived another classic movie monster with The Phantom of the Opera. This remake can't compare to the 1925 original with the great Lon Chaney. Two stars.

Any requests?

***

Slightly more original (although clearly influenced by the frequently filmed story The Hands of Orlac) was Hands of a Stranger. A concert pianist's hands are destroyed in an accident. In desperation, a surgeon transplants the hands of a recent murdered criminal onto the musician's wrists. Surprisingly, the pianist does not become possessed by the dead man. The horrible events that happen after the procedure result from the musician's rage at his inability to play. This was a modest but interesting movie, with some striking visuals and a great deal of unusual dialogue. Three stars.

That little boy is going to be very sorry he made fun of the way that man plays.

***

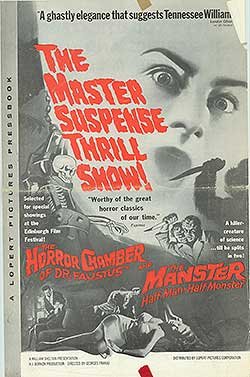

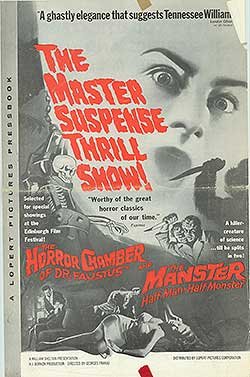

A most unusual double feature appeared in movie houses in 1962.

The unwieldy title The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus is the disguise worn by the French film Les yeux sans visage (The Eyes Without a Face), dubbed and edited for American audiences. A physician kidnaps women in order to surgically remove their faces and transplant them onto his daughter, whose own face was ruined in an accident. The replacements do not last long, so he must repeat his crimes many times. Despite this disturbing plot, the film is surprisingly beautiful and darkly poetic. Four stars, and I can only hope that a subtitled, unedited version will be available some day.

***

The daughter, hidden under the mask she wears between transplants.

The Manster is an American production filmed in Japan, with a mostly Japanese cast and crew. An American reporter interviews a Japanese scientist, who secretly injects him with an experimental formula. An extra eyeball appears on his shoulder, eventually growing into a second head. This movie is even more bizarre than I've made it sound. I can't say it's a good film, but the sheer weirdness of it holds the viewer's attention. Two stars.

Not what you want to see in the mirror.

***

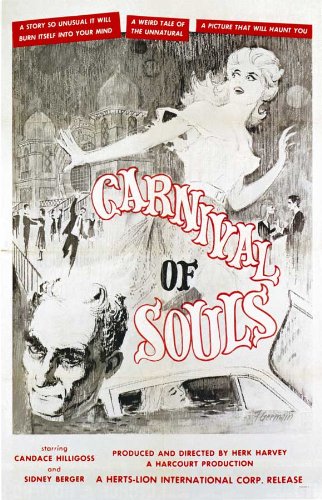

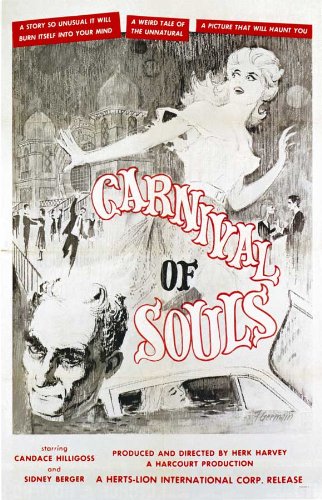

Made on a tiny budget by a director of documentary short subjects, Carnival of Souls overcame its limitations to become a haunting tale of life after death. A woman survives a car accident. Later she is haunted by ghoulish figures. The story is simple enough for an episode of Twilight Zone, but the film creates a genuinely eerie mood. Four stars.

The haunting begins.

***

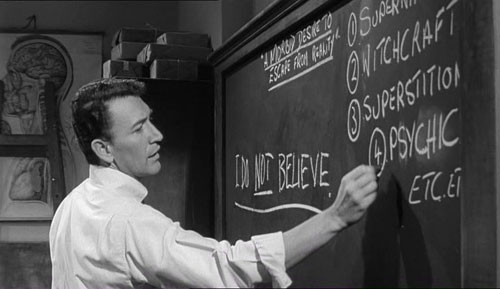

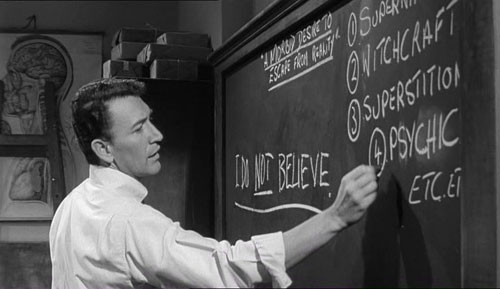

The best horror film of 1962 was probably the British production Night of the Eagle (released in the USA as Burn Witch Burn.) The script is skillfully adapted from Fritz Leiber's classic 1943 novel Conjure Wife by talented fantasy writers Charles Beaumont and Richard Matheson, as well as British screenwriter George Baxt, who wrote another excellent chiller a couple of years ago, The City of the Dead (known in American as Horror Hotel.) As in the novel, a skeptical college professor is married to a woman who secretly uses conjuring spells to protect her husband. When he discovers her magical objects, he forces her to destroy them. Things go rapidly downhill from there, as the professor discovers to his horror that witchcraft is very real, and that someone is using black magic to destroy his career, his marriage, and his life. The movie is exquisitely filmed, with fine acting and a dramatic climax. Five stars.

The professor at work.

Confronting his wife about her use of magic.

Up to no good.

***

Although it contains no supernatural elements, I would like to end this discussion with the psychological thriller Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?. Like Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho of a few years ago, it explores the darkest places within the human mind. Legendary actresses Bette Davis and Joan Crawford play sisters with a history of bad blood between them. Crawford is confined to a wheelchair, and Davis is as mad as a hatter. She was a child star many years ago, and she still dresses like a little girl, her aging face covered with grotesquely heavy layers of makeup. As Baby Jane's mind continues to deteriorate, the rivalry between the sisters (a reflection of the dislike the two stars had for each other, according to Hollywood gossip) leads to horrible consequences. Davis gives a bravura performance. Four stars.

***

And… there were other kinds of film released in 1962, I suppose. But they are beyond the scope of this article. Until the next sf, fantasy, or horror flick hits the cinema, see you at the movies!

[P.S. If you registered for WorldCon this year, please consider nominating Galactic Journey for the "Best Fanzine" Hugo. Check your mail for instructions…]