by Gideon Marcus

Every month, science fiction stories come out in little digest-sized magazines. It used to be that this was pretty much the only way one got their SF fix, and in the early '50s, there were some forty magazines jostling for newsstand space. Nowadays, SF is increasingly sold in book form, and the numbers of the digests have been much reduced. This is, in many ways, for the good. There just wasn't enough quality to fill over three dozen monthly publications.

That said, though there are now fewer than ten regular SF mags, editors still can find it challenging to fill them all with the good stuff. Editor Fred Pohl, who helms three magazines, has this problem in a big way. He saves the exceptional stories and known authors (and the high per word rates) for his flagship digest, Galaxy, and also for his newest endeavor, Worlds of Tomorrow. That leaves IF the straggler, filled with new authors and experimental works.

Sometimes it succeeds. Other times, like this month, it is clear that the little sister in Pohl's family of digests got the short end of the stick. There's nothing stellar in the May 1963 IF, but some real clunkers, as you'll see. I earned my pay (such as it is) this month!

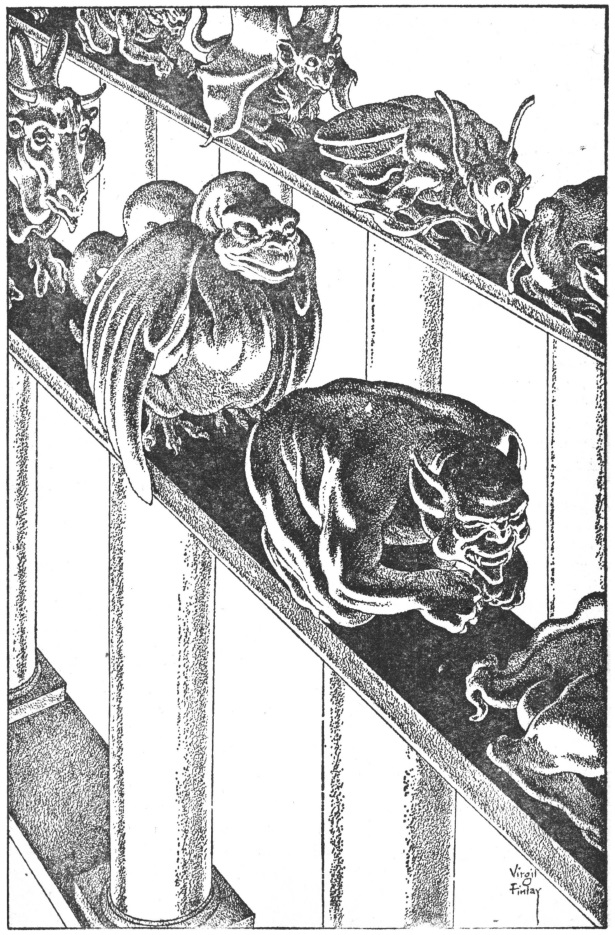

The Green World, by Hal Clement

Hal Clement (or Harry Stubbs, if you want to know the name behind the pseudonym) has made a name for himself as a writer of ultrahard science fiction, lovingly depicting the nuts and bolts of accurate space-borne adventure. The Green Planet details the archaeological and paleontological pursuits of a human expedition on an alien planet. The puzzle is simple — how can a world not more than 50 million years old possess an advanced ecosystem and a hyper-evolved predator species?

Clement's novella, which comprises half the issue, is not short on technical description. What it lacks, however, is interesting characters and a compelling narrative. I bounced off this story several times. Each time, I asked myself, "Is it me?" No, it's not. It's a boring story, and the pay-off, three final pages that read like a cheat, aren't worth the time investment. One star.

Die, Shadow!, by Algis Budrys

Every once in a while, you get a story that is absolutely beautiful, filled with lyrical writing, and yet, you're not quite sure what the hell just happened. Budrys' tale of a modern-day Rip van Winkle, who sleeps tens of thousands of years after an attempted landing on Venus, is one of those. I enjoyed reading it, but it was a little too subtle for me. Still, it's probably the best piece in the issue (and perhaps more appropriate to Fantastic). Three stars.

Rundown, by Robert Lory

Be kind to the worn-out bum begging for a dime — that coin might literally spell the difference between life and death. A nicely done, if rather inconsequential vignette, from a first-time author. Three stars.

Singleminded, by John Brunner

In the midst of a ratcheted-up Cold War, a stranded moon-ferry pilot is rescued by a chatty Soviet lass. The meet cute is spoiled, by turns, first by the unshakable paranoia the pilot feels for the Communist, and second by the silly, incongruous ending. I suspect only one of those was the writer's intention. Three stars.

Nonpolitical New Frontiers, by Theodore Sturgeon

ans. Al Landau, gideon marcus, hal clement, harry s

Sturgeon continues to write rather uninspired, overly familiar non-fiction articles for IF. In this one, Ted points out that fascinating science doesn't require rockets or foreign planets — even the lowly nematode is plenty interesting. Three stars.

Another Earth, by David Evans and Al Landau

When I was 14, (mumblety-mumblety) years ago, I wrote what I thought was a clever and unique science fiction story. It featured a colony starship with a cargo of spores and seeds that, through some improbable circumstance, travels in time and ends up in orbit around a planet that turns out to be primeval Earth. The Captain decides to seed the lifeless planet, ("Let the land produce…") thus recreating the Biblical Genesis.

I did not realize that Biblically inspired stories were (even then) hardly original. In particular, the Adam and Eve myth gets revisited every so often. It's such a hoary subject that these stories are now told with a wink (viz. Robert F. Young's Jupiter Found and R.A. Lafferty's In the Garden).

Why this long preface? Because the overlong story that took two authors (and one undiscerning editor) to vomit onto the back pages of IF is just a retelling of the Noah myth. An obvious one. A bad one. One star.

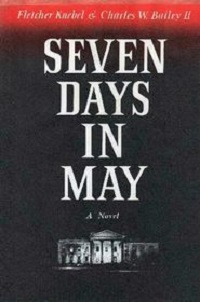

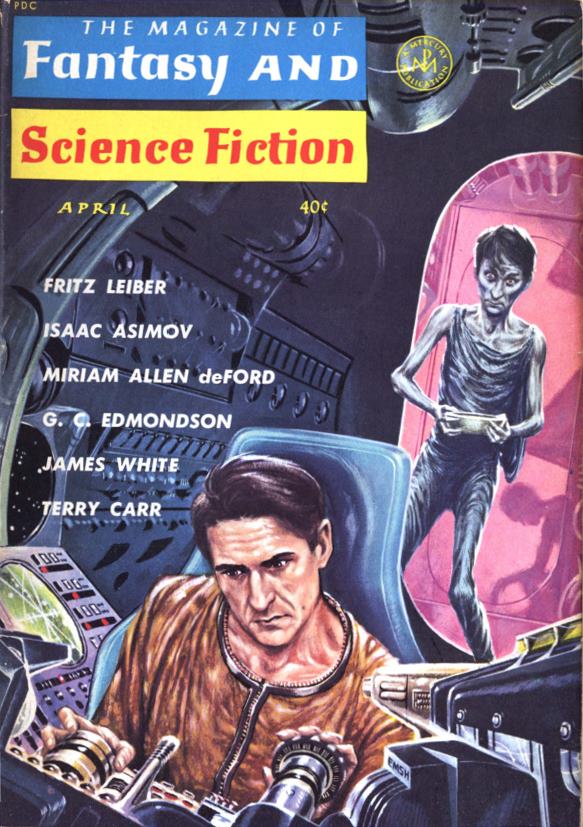

Turning Point, by Poul Anderson

Last up, the story the cover illustrates features a concept you won't find in Analog. A crew of terran explorers finds a planet of aliens that, despite their primitive level of culture, are far more intelligent than humans. The story lasts just long enough for us to see the solution we hatch to avoid our culture being eclipsed by these obviously superior extraterrestrials. Not bad, but it suffers for the aliens being identical to humans. Three stars.

Thus ends the worst showing from IF in three years. Here's a suggestion: raise the cover price to 50 cents and pay more than a cent-and-a-half per word?