by John Boston

Is something stirring at Amazing? After several issues devoid of non-fiction features, this one starts a book review column by Harry Harrison, whose brief stint as nominal editor of the British magazine SF Impulse ended a few months ago. Is a remake in order? A change of guard in the wind? There’s no hint.

by Johnny Bruck

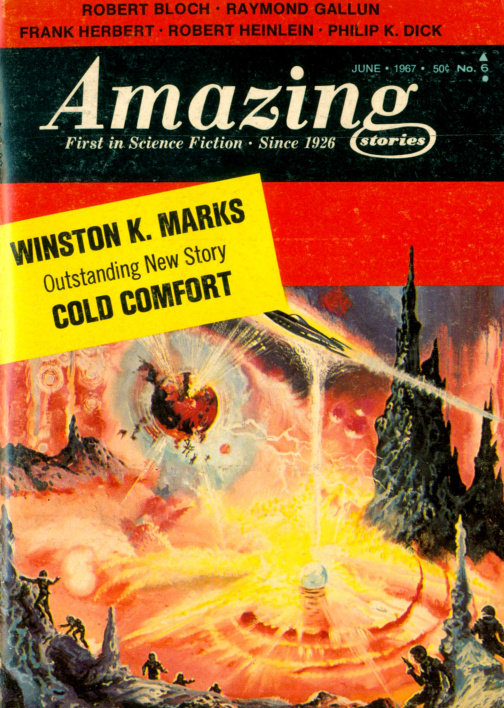

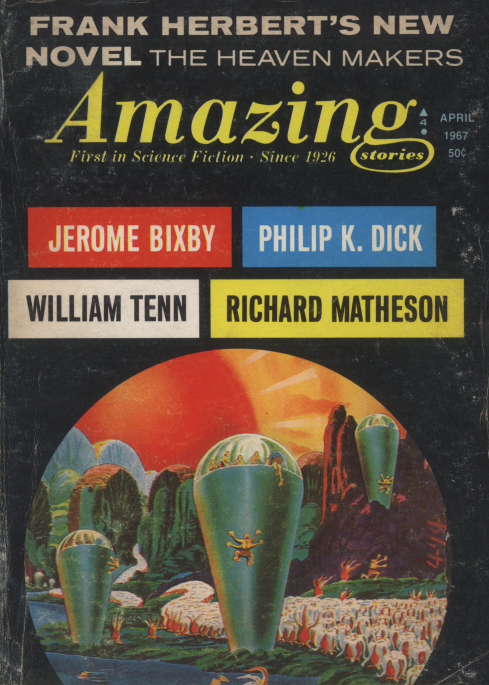

The cover itself is also a change, not having been looted from the back files of Amazing or Fantastic Adventures. The pleasantly lurid image of space-suited men watching or fleeing a battle of spacecraft is not credited, but other sources attribute it to a 1964 issue of Perry Rhodan, Germany’s long-running weekly paperback novella series, artist’s name Johnny Bruck. I wonder if the publisher is paying him, or anyone.

Also perplexing is the shift in presentation on the cover. Last issue, the display of big names was ostentatious. Here, the only thing prominently displayed is “Winston K. Marks Outstanding New Story Cold Comfort,” sic without apostrophe. Marks is one of the legion who filled the mid-1950s’ proliferation of SF magazines with competent and forgettable copy. After a couple of stories in the early ‘40s, he reappeared with a few in 1953, contributed a staggering 25 stories in 1954 and 20 in 1955, and trailed off thereafter; he hasn’t been seen in these parts since mid-1959. But here he is, name in lights, while Robert Heinlein, Frank Herbert, and Philip K. Dick are relegated to small type over the title. Odd, and probably counter-productive, to say the least.

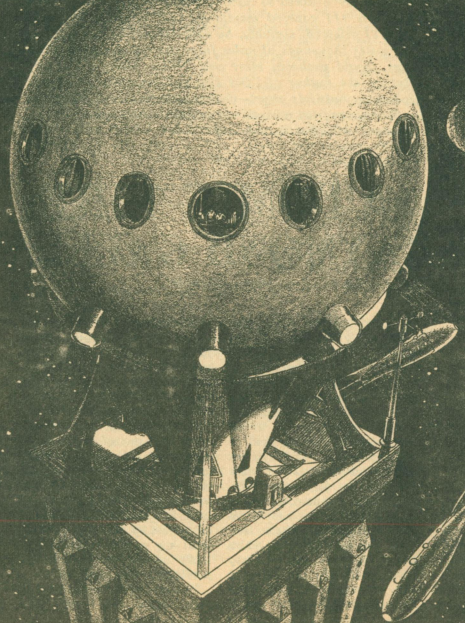

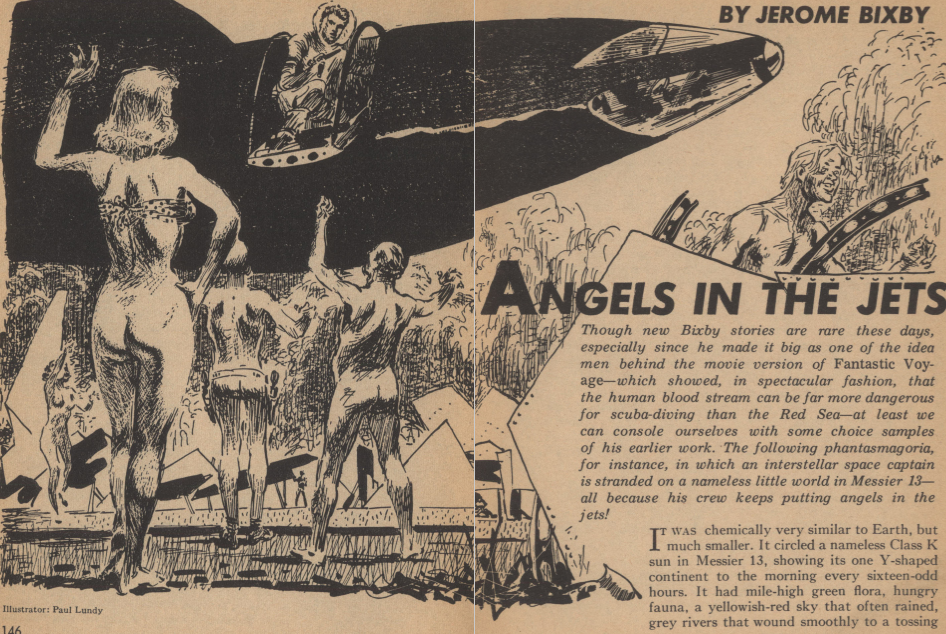

The Heaven Makers (Part 2 of 2), by Frank Herbert

Frank Herbert’s serial The Heaven Makers concludes in this issue. Imagine an SF novel oriented to the reference points of Charles Fort, Richard Shaver, and soap opera. And then imagine—this is the hard part—that it’s nonetheless pretty readable.

First, we are property! Just like Charles Fort said. You may think you understand human history, but everything you know is wrong! Earth is secretly dominated by the Chem, a species of very short, bandy-legged, silver-skinned alien humanoids who have been made immortal, and also connected tele-empathically, by a discovery of one of their ancient savants—Tiggywaugh’s web (definitely sic). Only problem is . . . they’re bored. Eternity weighs heavily on them. They must be entertained and distracted!

So, the Chem send Storyships around the galaxy, though Earth’s is the only one we see. This ship rests on the bottom of the ocean, from which vantage the Chem shape history in large and small ways both by direct intervention and by remote manipulation and heightening of human emotional states. The result: wars that might be settled quickly at the conference table can be prolonged and intensified, and susceptible individuals can be driven as far as murder. These events are recorded, processed, spiced up with their own emotional track, and broadcast to pique the jaded souls of the Chem.

One of the stars of this industry is Fraffin, proprietor of Earth’s Storyship, but he’s suspected of letting hints drop to Earthfolk about what’s going on, a major crime among the Chem. Kelexel, posing as a visitor, has been sent by the authorities to get to the bottom of things, after four previous investigators have found nothing and, suspiciously, resigned. But Kelexel is quickly corrupted himself. Fraffin shows him a “pantovive” of a man manipulated by the Chem into murdering his wife, which Kelexel finds quite gripping. He also becomes obsessed with the woman’s daughter, Ruth (the Chem are quite captivated by the physiques of humans, and can interbreed with them). Fraffin, having found Kelexel’s vulnerability, sets out to procure her for him. So three dwarfish figures show up at her back door, immobilize her with some sort of ray, and carry her away to be mind-controlled and ravished by Kelexel.

At this point, the nagging sense of familiarity I was feeling came into focus. Herbert has reinvented Richard Shaver’s Deros! Shaver, a former psychiatric patient, wrote up his delusions of sadistic cave-dwelling degenerates tormenting normal people, which (with much reworking by editor Ray Palmer) boosted Amazing’s mid-1940s circulation to unheard-of levels, until the publisher put an end to the disreputable spectacle a few years later. Now Herbert has gussied up the “Shaver Mystery” for prime time! The distorted physical appearance . . . check. The mind control rays . . . check. The underground caverns . . . not exactly, these characters are underwater instead. But that’s a minor detail.

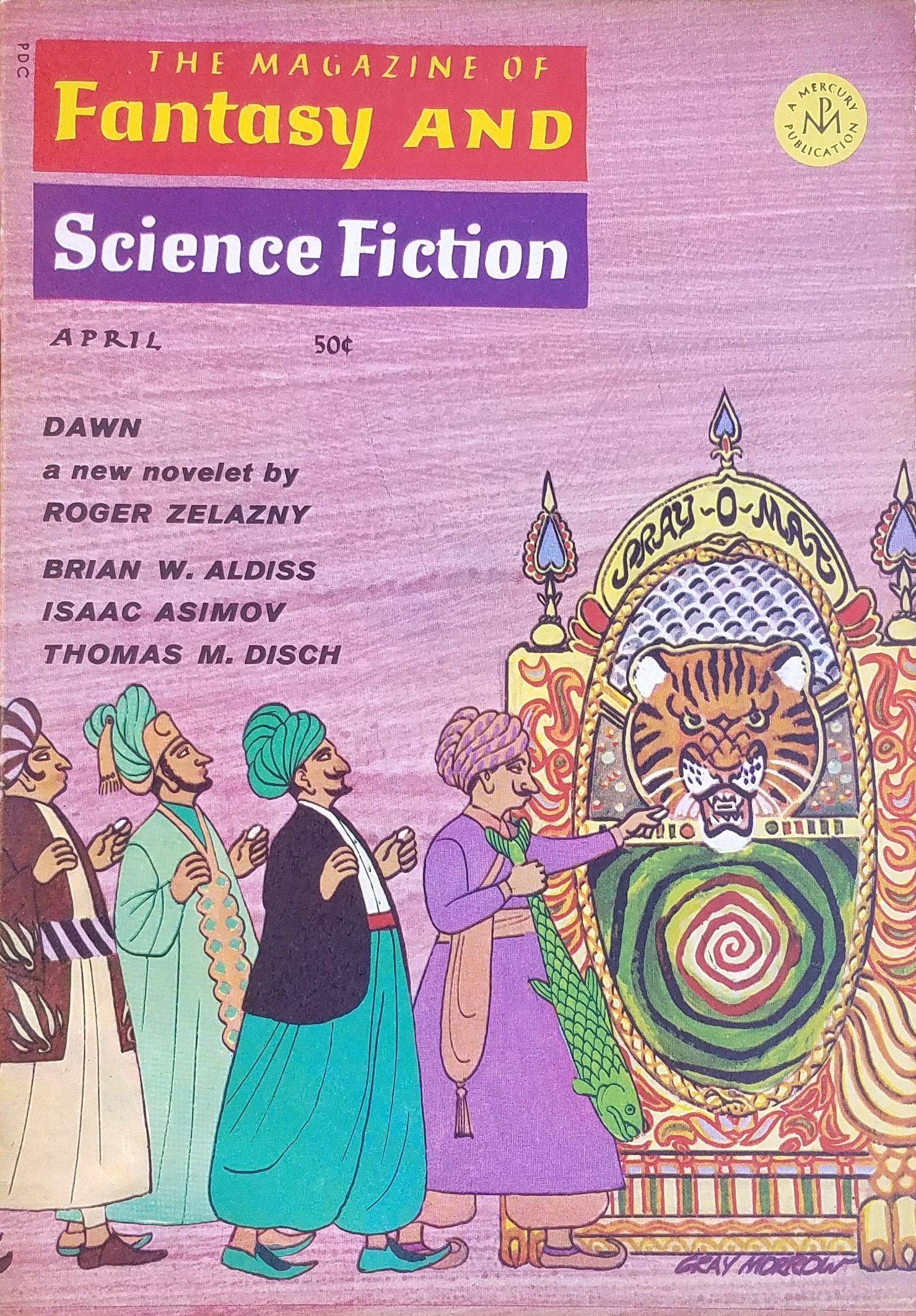

by Gray Morrow

Oh, yes, the soap opera part. Up on dry land, Andy Thurlow, a court psychologist, is Ruth’s old boyfriend; she threw him over for someone else, who turned out to be a low-life. Andy’s never gotten over it. Her father, holed up after his Chem-driven murder of her mother, won’t surrender to anybody but Andy. Meanwhile, Andy, who is wearing polarized glasses as a result of an eye injury, has started to see what prove to be manifestations of Chem activity, invisible to anyone else. Andy also gets back with Ruth, who has moved out on her husband; he takes her back to the marital house and waits so she can pick up some possessions. But the Chem snatch her as described, and her husband falls through a glass door and dies.

Back at the Chems’ submarine hideout, Kelexel is having his way with the pacified Ruth, who, when he’s not using her, studies the Chem via the pantovive machine, learning more and more, while Kelexel harbors growing misgivings about the whole Chem enterprise. Andy, up on land, is trying to persuade Ruth’s father the murderer to cooperate with an insanity defense while wondering if the strange manifestations he has seen account for Ruth’s disappearance. The plot lines are eventually resolved in confrontations among Kelexel, Fraffin, Ruth, and Andy with dialogue that is more reminiscent of daytime TV than Herbert’s turgid usual. In the end, Herbert actually makes a readable story out of this sensational and largely ridiculous material. Three stars.

Cold Comfort, by Winston K. Marks

by Gray Morrow

Winston Marks’s "Outstanding New Story" Cold Comfort is an amusing first-person rant by the first man to be cryogenically frozen for medical reasons and revived when his problem can be cured. He’s pleased enough with his new kidneys, but isn’t impressed by this brave new world in which corporations now overtly dominate the world, there’s a nine-million-soldier garrison in East Asia, etc. etc. E.g. , “I am only now recovering from my first exposure to your local art gallery. Who the hell invented quivering pigments?” It’s at best a black-humorous comedy routine, but well enough done. Three stars.

The Mad Scientist, by Robert Bloch

by Virgil Finlay

After Marks it is downhill, or over a cliff. The Mad Scientist by Robert Bloch, from Fantastic Adventures, September 1947, is a deeply unfunny farce about an over-the-hill scientist who works with fungi, who has a young and beautiful wife with whom the protagonist is having an affair. They want to get rid of the scientist with an extract of poisonous mushrooms, but he outsmarts them, and what a silly bore. The fact that the protagonist is a science fiction writer and the story begins with some blather about how dangerous such people are does not enhance its interest at all. One star.

Atomic Fire, by Raymond Z. Gallun

by Leo Morey

Raymond Z. Gallun’s Atomic Fire (Amazing, April 1931) is a period piece, Gallun’s third published story, in which far-future scientists Aggar Ho and Sark Ahar (with huge chests to breathe the thin atmosphere, spindly and attenuated limbs, large ears, a coat of polar fur—evolution!) have discovered that the Black Nebula is about to swallow up the sun and kill all life on Earth. The solution? Atomic power, obviously, to be tested off Earth for safety (the spaceship has just been delivered). Unfortunately, their experiments first fail, then succeed all too well; but Sark Ahar’s quick thinking turns disaster into salvation! As the blurb might have read. Gallun had an imagination from the beginning, but the stilted writing makes this one hard to appreciate in these modern days of the 1960s. Two stars.

Project Nightmare, by Robert Heinlein

by William Ashman

In Robert Heinlein’s Project Nightmare, from the April/May 1953 Amazing, the Russians deliver an ultimatum demanding surrender, since they’ve mined American cities with nuclear bombs. The only hope is a colorful and miscellaneous bunch of clairvoyants to locate the bombs before they go off. It’s a fast-moving but superficial, wisecracking story, a considerable regression for the author. Some years ago he published an essay titled On the Writing of Speculative Fiction, and presented five rules for the aspiring writer. I think this story must illustrate the last two: “4. You must put it on the market. 5. You must keep it on the market until sold.” I suspect Heinlein intended this one for the slicks, and when none of them would have it, started down the ranks of the SF mags until it finally came to rest in Amazing, which, compounding the indignity, managed to lose his customary middle initial. Two stars.

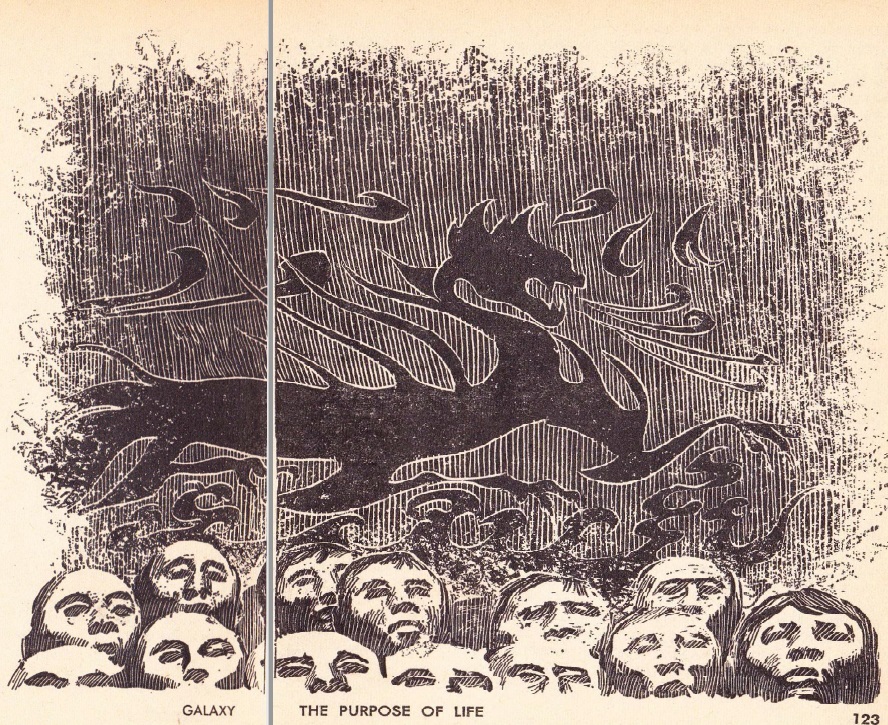

The Builder, by Philip K. Dick

by Ed Emshwiller

Philip K. Dick’s The Builder (Amazing, December 1953/January 1954) is from his early Prolific Period—he published 31 stories in the SF magazines in 1953 and 28 in 1954, handily beating Winston K. Marks’s peak. How? With a certain number of tossed-off ephemerae like this one, in which an ordinary guy is obsessed for no reason he can articulate with building a giant boat in his backyard. A rather peculiar boat too, with no sails or motor or oars. And then: “It was not until the first great black drops of rain began to splash about him that he understood.” That’s it. Two stars for this shaggy-God story which is unfortunately not shaggy enough.

Summing Up

Well, that was pretty dreary. The issue’s only distinction is the unexpected readability of Herbert’s novel, which is the best, or least bad, of the serials this publisher has run. The most one can say about the reprint policy is that it has its ups and downs, and this issue is definitely the latter.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[May 6, 1967] Stirred? Shaken? (June 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/amz-0667-cover-504x372.png)

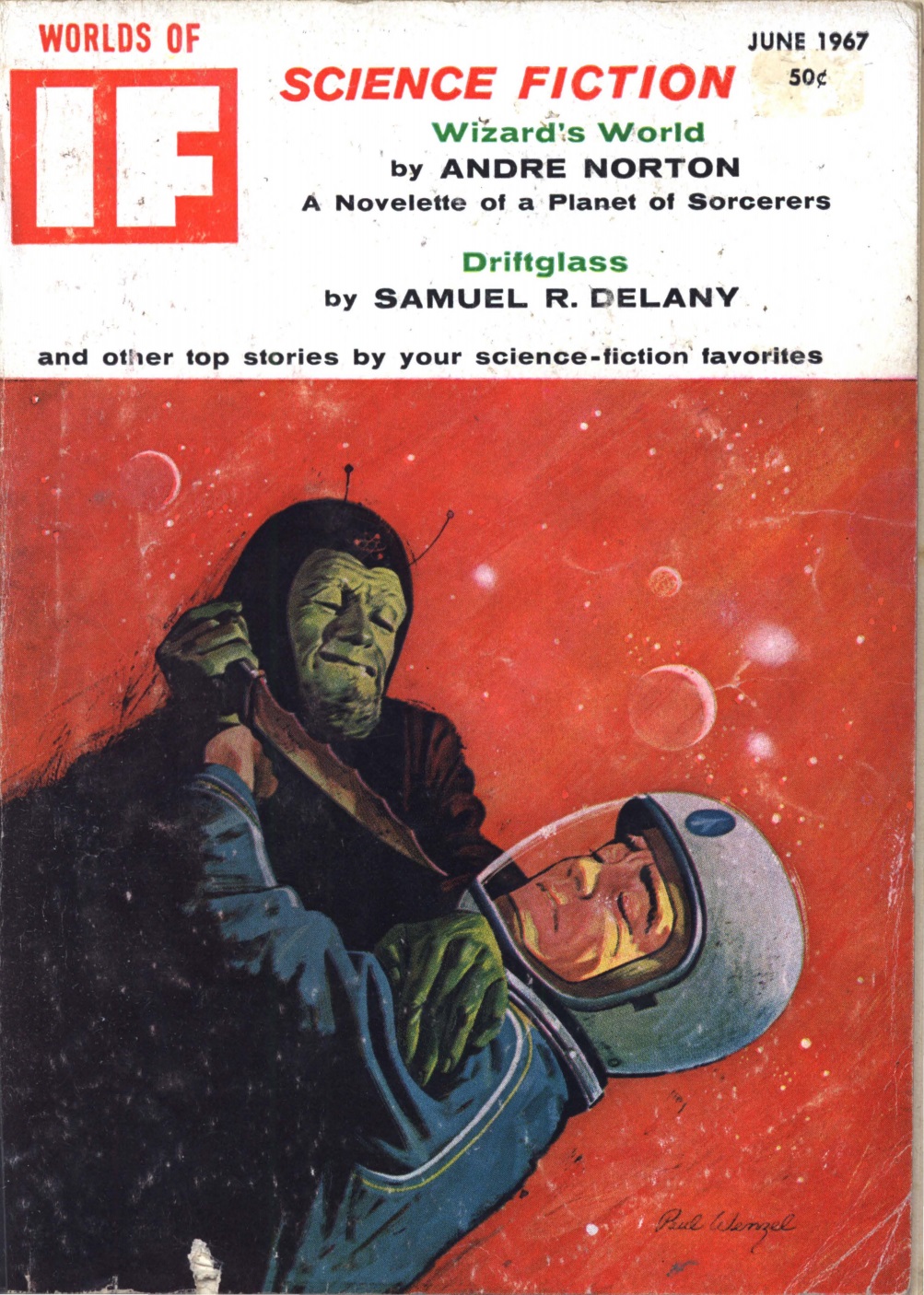

![[May 2, 1967] The Call of Duty (June 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/IF-Cover-1967-06-672x372.jpg)

Muhammad Ali is escorted from the induction center in Houston, Texas.

Muhammad Ali is escorted from the induction center in Houston, Texas.  Uncle Martin and Tim (from My Favorite Martian) seem to have had a falling out. Actually, this is supposedly from Spaceman!

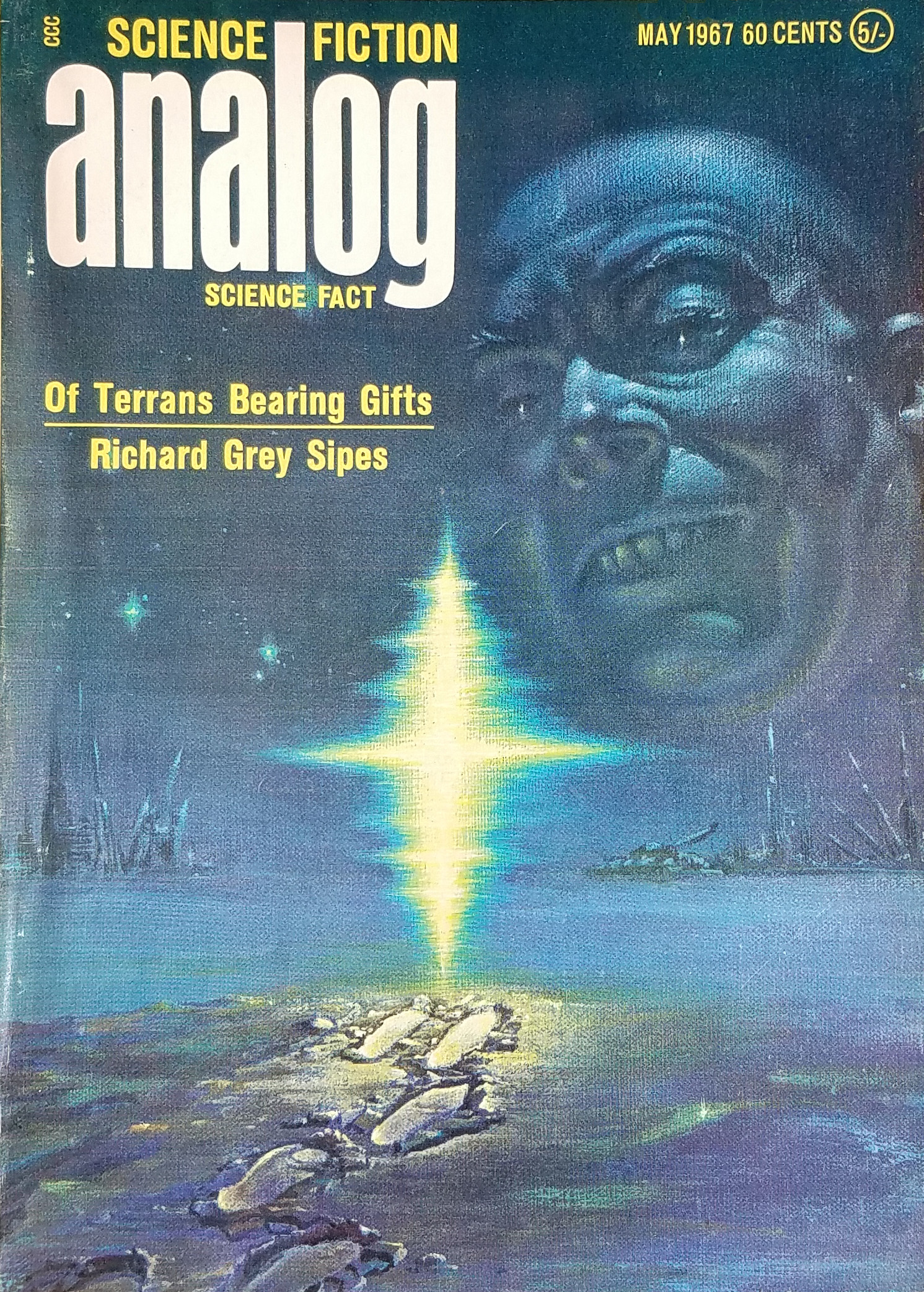

Uncle Martin and Tim (from My Favorite Martian) seem to have had a falling out. Actually, this is supposedly from Spaceman!![[April 30, 1967] Strange New Worlds and Staid Old Ones (May 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/670430cover-672x372.jpg)

![[April 4, 1967] Transitions (May 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/IF-Cover-1967-05-672x372.jpg)

What are these robots up to? Art by Gaughan

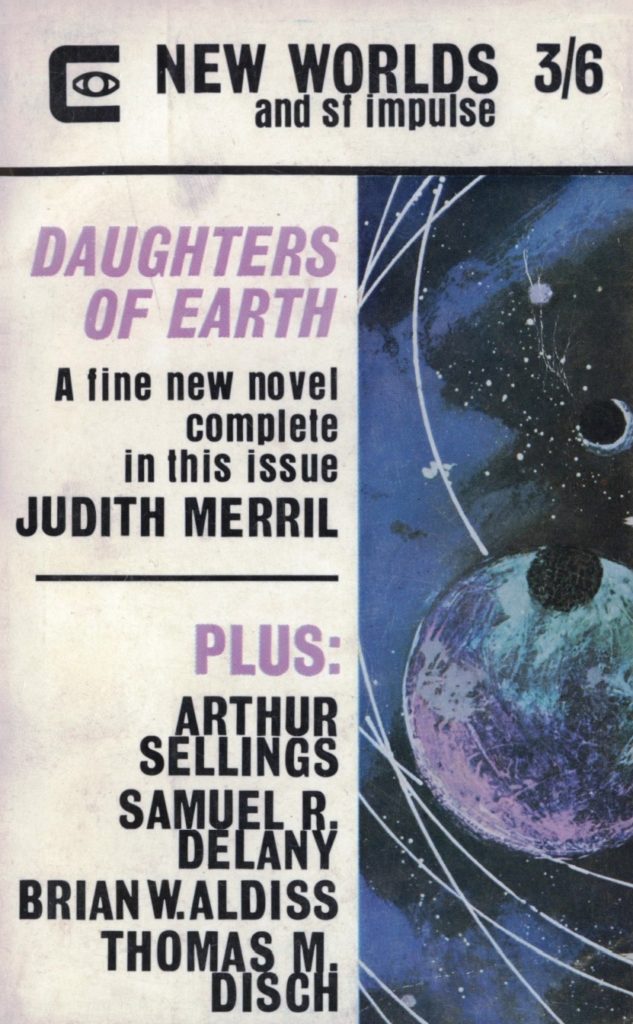

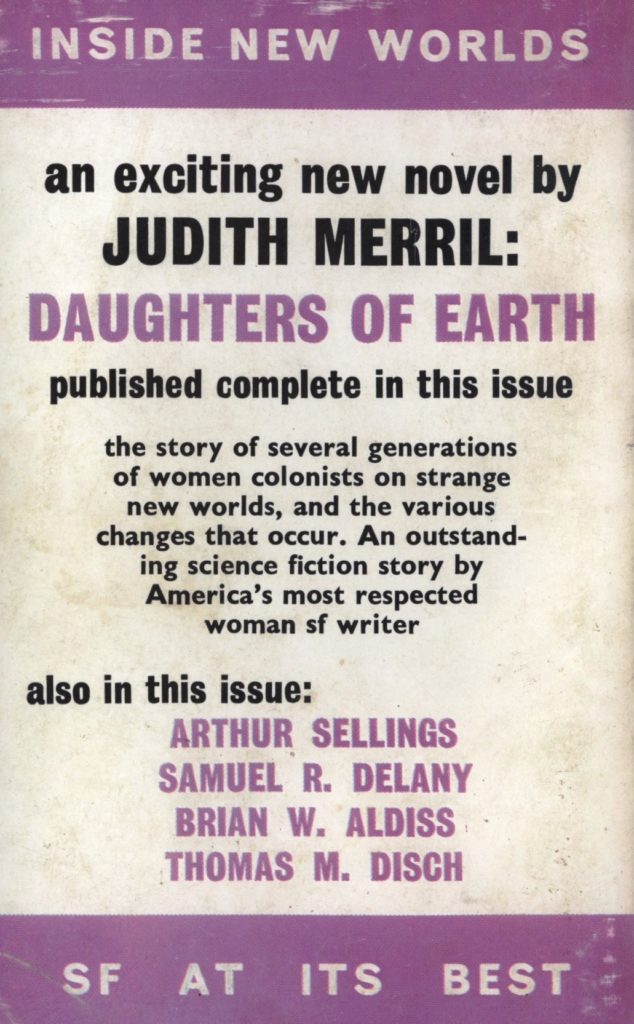

What are these robots up to? Art by Gaughan![[March 26, 1967] Changes Coming <i>New Worlds and SF Impulse</i>, April 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/New-Worlds-April-1967-672x372.jpg)

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

![[March 20, 1967] Vistas near and far (April 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670320cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 14, 1967] Family Matters (April 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/amazing-apr-1967-cover-489x372.png)

![[March 10, 1967] Mediocrités, Slayer of Magazines (April 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670310cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 4, 1967] Mediocrities (April 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/IF-Cover-1967-03-672x372.jpg)

![[February 28, 1967] The Big Stall (March 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670228cover-672x372.jpg)