If you are a devout follower of my column, you know that I love First Contact stories. From Arthur C. Clarke to William Tenn, I love a good yarn about the meeting of two races. Lucky for me, Daniel Galouye (a fairly seasoned writer from Louisiana), has delivered a solid, if not outstanding, addition to my library of such stories.

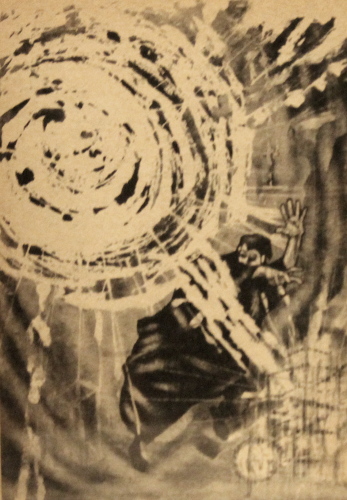

The City of Force kicks off the April issue of Galaxy. Here's the set-up: not too far in the future (it can't be too far–the conversational slang is all straight out of today's movies), incorporeal spherical aliens show up and blow up all of our cities. They set up shop, erecting cities of their own. These cities are just as insubstantial as the aliens. They are towering, radiant, multi-hued things, whose walls of force shift to fulfill every need of the aliens, from shelter to sustenance. Humanity is left to scratch out a primitive existence in the wilderness. Any attempt to use electricity is met with vindictive zapping.

Except some humans have figured out how to live inside the cities. They have discovered that the alien force fields are activated by thought–any sentient thought. And so the humans live within the walls of the alien city like rats. Their life is virtually idyllic. There is plenty of food, and it tastes like whatever one wants. The force fields mold easily into furniture and even conveyances.

Of course, every so often, the aliens try to exterminate the human vermin, just as we might do with rats, but the risk is considered worth it.

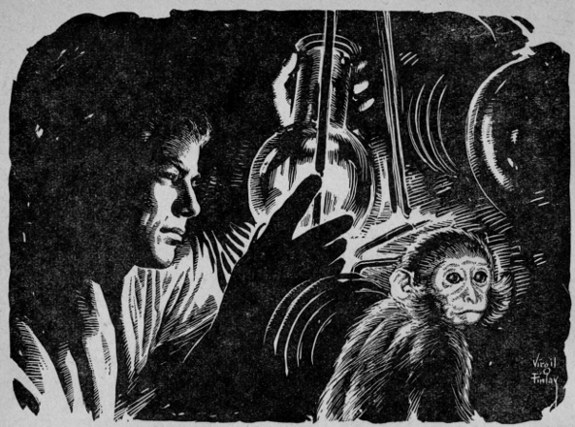

Enter Bruno, a young man from one of the wilderness tribes. His destination is one of the cities. His intention: to make contact with the aliens and convince them that we are sentient and deserve to be able to coexist on Earth. Once in the city, he discovers he has a particular affinity for force field manipulation, and a few experiments establish his ability to convert harmless yellow and green constructs into explosive red ones.

At first, the city-dwellers welcome Bruno and try to convert him to their posh style of living. Bruno eats better than ever before, falls in love, and nearly succumbs to temptation. But only nearly. Spurning the trappings of comfort, Bruno redoubles his efforts to make contact despite the danger. When his attempts are at last successful, the story reaches a genuine climax of excitement.

Unfortunately, what ensues is rather rushed and disappointing. Once communication is established, the aliens lose all of their mystery and become rather pedestrian human analogues. I won't spoil the ending, but I wish Galouye had written a longer story and kept the aliens more mysterious. Tenn did a better job in Firewater.

Still, there are a lot of good ideas in this story. The force cities are very well realized and interesting. The aliens are suitably alien throughout most of the story. The characters are reasonably well realized, though their incessant use of modern slang is jarring, particularly when the story is supposed to take place several hundred years in the future.

Next up–the rest of the magazine… unless events overtake me again. Let's hope the news is better next time.

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.