I mentioned last week that Satellite no longer prints full-length novels between its covers anymore. It looks like that role is now going to Galaxy, which, in its new, 196-page format, can accommodate longer works more comfortably. In short order, it looks like Galaxy will specialize in two-part serials, responding to reader requests for same.

I'm a fan of longer stories in my magazines. F&SF scratches my short story itch quite nicely, and there are lots of good science fiction novels coming out, so that intermediate length can only be found in the digests. I find that the novella/short novel length is quite good for adequately developing a concept without overly padding the matter.

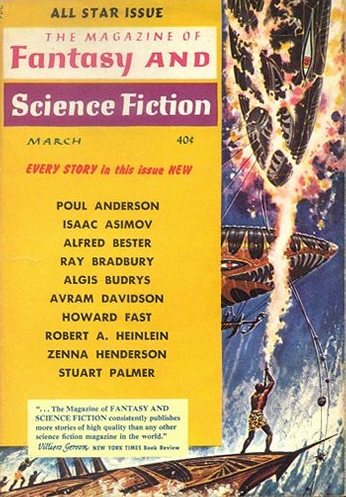

Cover by EMSH

That length was certainly used to excellent effect in Fred Pohl's new space exploration/first-contact thriller, Whatever Counts. What a fine story. With the exception of some over-traditional gender roles (in the far future, I'd expect women to be more than secretaries and babysitters), Pohl paints a quite mature and sophisticated vision of tomorrow. Moreover, while the female characters have traditional roles, they also get to be intelligent and vital protagonists. Just skip over the rather exploitative art…

So what's the story actually about? The Explorer II, essentially a generation colony ship, though the journey "only" takes about seven years, is part of humanity's first gasp of interstellar expansion. Unfortunately, during the vessel's journey, our race (as a whole) makes contact with its first alien species, the technologically and biologically more-sophisticated "Gormen." Wherever we encounter the Gormen, we are able to offer but feeble resistance.

The same is true for several of the crew of the Explorer II, who are quickly captured by the Gormen upon touchdown. Their trials at the hands of the Gormen, and the nifty way in which they make escape, are all interesting and well-written. But what really sold me was the attention to detail. The colony ship is plausible, the Gormen truly alien, the characters well-realized, and the style both gritty and artistic. And I really like any story that takes the time to explain where characters are going to take care of their toilet needs…

illustration by WOOD

I'd hate to spoil any more than I already have. Just go read it! (Please note that the author has not given me permission to freely distribute this story. If you can, I'd buy a copy.)

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.