Human beings look for patterns. We espy the moon, and we see a face. We study history and see it repeat (or at least rhyme, said Mark Twain). We look at the glory of the universe and infer a Creator.

We look at the science fiction genre and we (some of us) conclude that it is dying.

Just look at the number of science fiction magazines in print in the early 1950s. At one point, there were some forty such publications, just in the United States. These days, there are six. Surely this is an unmistakable trend.

Or is it? There is something to be said for quality over quantity, and patterns can be found there, too. The last decade has seen the genre flower into maturity. Science fiction has mostly broken from its pulpy tradition, and many of the genre's luminaries (for instance, Ted Sturgeon and Zenna Henderson) have blazed stunning new terrain.

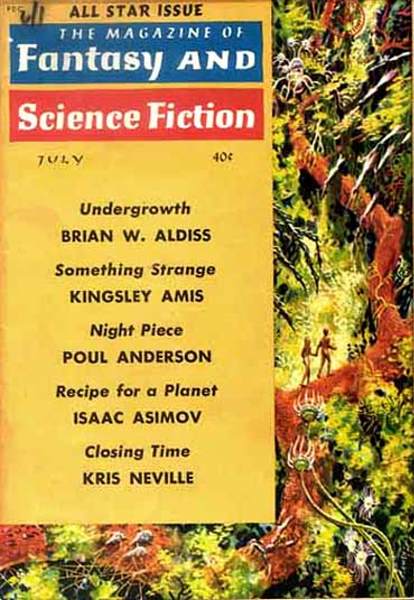

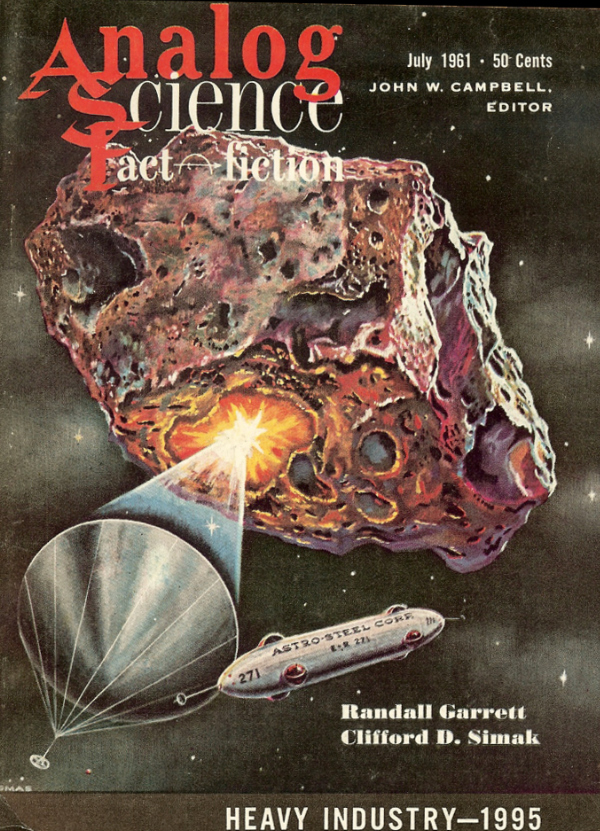

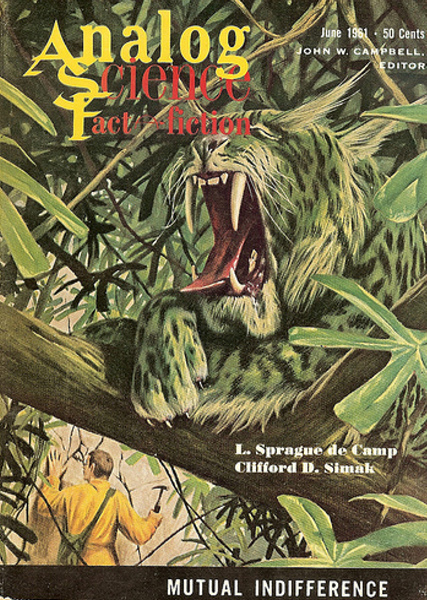

I've been keeping statistics on the Big Three science fiction digests, Galaxy, Analog, and Fantasy and Science Fiction since 1959. Although my scores are purely subjective, if my readers' comments be any indication, I am not too far out of step in my assessments. Applying some math, I find that F&SF has stayed roughly the same, and both Analog and Galaxy have improved somewhat.

Supporting this trend is the latest issue of Galaxy (August 1961), which was quite good for its first half and does not decline in its second.

For instance, Keith Laumer's King of the City is an exciting tale of a cabbie who cruises the streets of an anarchic future. The cities are run by mobs, and the roads are owned by automobile gangs. It's a setting I haven't really seen before (outside, perhaps, of Kit Reed's Judas Bomb), and I dug it. In many ways, it's just another crime potboiler, but the setting sells it. Three stars.

Amid all of the ugly headlines, the blaring rock n' roll, the urban sprawl, do you ever feel that the romance has gone out of the race? That indefinable spark that raises us to the sublime? Lester del Rey's does, and in Return Engagement, his protagonist discovers what we've been missing all these years. A somber piece, perhaps a bit overwrought, but effective. Three stars.

Willy Ley's science column, For your Information, is amusing and educational, as usual, though its heyday has long past. This time, the subject is the preeminent biologist, Dr. Theodore Zell, whom Dr. Ley never got to meet, though he tried. Three stars.

Deep Down Dragon, by Judith Merril, depicts a lovers' jaunt on Mars that ends in a brush with danger. Told in Merril's deft, artistic style, the rather typical boy-rescues-girl story isn't all it appears to be. Three stars.

I can't lay enough praise upon the final novella, Jack Vance's The Moon Moth. Science fiction offers a large number of themes and techniques that provide building blocks for stories. Every once in a while, a writer creates something truly new. Vance gives us Sirenis, a planet whose denizens communicate with musical accompaniment that conveys mood beyond that inherent in words. Moth is a murder mystery, and that story is interesting in and of itself, but what really makes this piece is the struggle of the Terran investigator to master the native modes of communication and to overcome the pitifully low status that being a foreigner affords. Really a beautiful piece. Five stars.

That puts the total for this issue at a respectable 3.4 stars. So far as I can tell, science fiction has got some life left in it…