[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Victoria Silverwolf

July isn't quite over yet, and already I feel overwhelmed by all that's been going on in the world:

Two new nations, Rwanda and Burundi, have been created from the Belgian territory of Ruanda-Urundi. Similarly, France has recognized the independence of its former colony Algeria.

Despite protests, the United States continues to test atomic weapons. The USA also detonated a hydrogen bomb in outer space, hundreds of miles above a remote part of the Pacific Ocean. The explosion created a spectacular light show visible from Hawaii, more than seven hundred miles away. It also disrupted electronics in the island state. An underground nuclear explosion created a gigantic crater in the Nevada desert and may have exposed millions of people to radioactive fallout.

AT&T launched Telstar, the first commercial communications satellite (which we'll be covering in the next article!)

The world of literature suffered a major loss with the death of Nobel Prize winning author William Faulkner.

In Los Angeles, young artist Andy Warhol exhibited a work consisting of thirty-two paintings of cans of Campbell's Soup.

The Washington Post published an article revealing how Doctor Frances Oldham Kelsey, a medical officer for the Food and Drug Administration, kept thalidomide, a drug now known to cause severe birth defects, off the market in the United States.

Even popular music seems to be going through radical changes lately. Early in the month the charts were dominated by David Rose's raucous jazz instrumental The Stripper. It would be difficult to think of a less similar work than Bobby Vinton's sentimental ballad Roses are Red (My Love), which has replaced it as Number One.

It seems appropriate that the latest issue of Fantastic offers no less than nine stories, one long and eight short, to go along with these busy days:

Sword of Flowers by Larry M. Harris

Vernon Kramer's cover art for the lead story captures something of the mysterious mood of this mythical tale. The setting is a strange world where the climate is so gentle that the inhabitants have no need for shelter. They also have the ability to create whatever they imagine. However, because their lives are so simple and happy, they rarely use this power. An exception is a man, twisted in mind and body, who comes up with the concepts of royalty and servitude, so that another man in love with a beautiful woman can become her slave. It all leads to tragedy, and an ending directed at the reader. It's a compelling legend written in poetic language. Five stars.

The Titan by P. Schuyler Miller

This issue's Fantasy Classic has a complex history. Serialized in part in the 1930's, although never published in full until revised for the author's 1952 collection, this is its first complete magazine appearance. The story takes place on a dying planet where the decadent upper class takes blood from the healthy lower class. The plebeian hero follows the patrician heroine above ground and falls in love. They become involved in a plot to violently overthrow the rulers and confront a huge, dangerous creature known as a Star Beast. Most readers will be able to figure out what planet is involved and the true nature of the Star Beast. Although said to be daring for the 1930's, it's pretty tame for the 1960's. Unfortunately, this is the longest story in the issue. Two stars.

Behind the Door by Jack Sharkey

A woman who seeks out dangerous experiences encounters a mysterious man whom she believes will provide the ultimate thrill. He turns out to be something other than expected. A fairly effective horror story. Three stars.

The Mynah Matter by Lawrence Eisenberg

A man determined to purchase a talking bird deals with a pet store owner who refuses to sell any of his animals. It seems that they are all reincarnations of famous people. This is a slight, whimsical comedy, but somehow likable. Three stars.

And a Tooth by Rosel George Brown

A woman whose husband and children die in an accident goes into a coma from the shock. Experimental brain surgery restores her to consciousness, but gives her two separate minds. The author does a good job of narrating from both points of view, and the effect is chilling. Four stars.

A Devil of a Day by Arthur Porges

This is yet another variation on the old deal with Satan theme. A man sells his soul for the chance to have absolute power over the city of Rome at a certain time during the Sixteenth Century. Readers familiar with a specific historical event will be able to predict why this is a very bad bargain. Two stars.

Continuity by Albert Teichner

A precocious student raises a peculiar question that haunts a physics teacher. If our universe consists of matter that we can sense and forces that we cannot sense, could the reverse be true in another universe? The result is unexpected. This is an odd, philosophical story, intriguing but not always clear. Three stars.

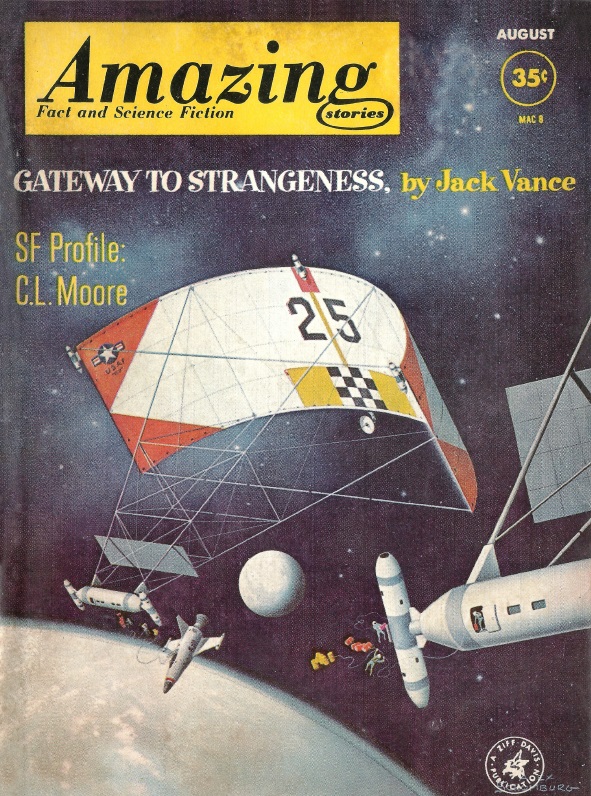

Horseman! by Roger Zelazny

A new writer, who also appears in this month's issue of Amazing, offers a brief prose poem. A mysterious rider appears in a village asking after others of his kind. What happens when he finds them is surprising. The story is beautifully written, and one hopes that the author will go on to produce longer works. Four stars.

Victim of the Year by Robert F. Young

A man down on his luck receives a note from a woman at the unemployment office. She claims to be an apprentice witch with the assignment to cast spells to make his life miserable. She repents of her actions, and together they must face the wrath of her coven. The story reads something like a less elegant version of a Fritz Leiber fantasy. Three stars.

The best stories in this issue are short ones, proving once again that good things come in small packages. Speaking of which, stay tuned for an article on the series of small packages circling the Earth that are making an outsized impact on their mother planet…

(P.S. Don't miss the second Galactic Journey Tele-Conference, July 29th at 11 a.m.! A chance to discuss Soviet and American space shots…and maybe win a prize!)

—