by Mark Yon

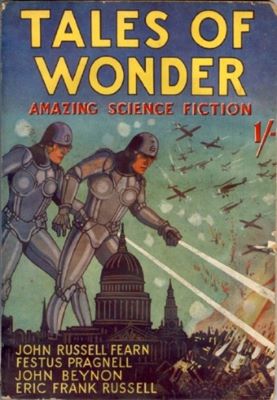

Scenes from England

Hello again!

After last month’s changes, I must admit that I was really looking forward to this month’s issues. I was intrigued – would the change of editor at SF Impulse be noticeable yet? And could editor Mike Moorcock over at New Worlds manage to produce another stellar issue of the same standard as last month?

I’ll start with New Worlds.

Mike Moorcock’s Editorial is not-an-Editorial. Instead Mike extolls a writer, reviewing some of their work. This is usually something that I feel belongs in the reviews section of the magazine.

However, Mike this time tells us of the work of J G Ballard, last seen here last month (and will appear again, later). The Editorial is typically enthusiastic, claiming that Ballard is the “first clear voice” of a new movement in science fiction. To which I mused that his voice is clearly different, whilst his plots are rather obscure.

To the stories!

Illustration by James Cawthorn

The Garbage World (Part 1 of 2), by Charles Platt

The cover story first. Platt tells of a future where Kopra, a world used by the rest of the Belt to dump its waste, has become increasingly unstable on account of the amount of waste dumped upon it. The people there strive to survive in a world with pollutive skies and garbage-covered landscapes.

However, the arrival of an official with a construction team to build a gravity generator, and deal with the problem before it becomes a hazard to others in the Belt, is greeted with suspicion. The general feeling is that the real motive is to get the locals off the planet and then steal their hoards of accumulated “wealth”.

This is made worse when Isaac Gaylord, the mayor of Kopra, has his wealth stolen and as his stockpile is a sign of his authority, he is deposed. Although suspicion immediately falls upon the construction team, Gaylord blames the nomads from outside of the village for taking advantage of the new situation. The work of the space constructors is also slowed by attacks on them, determined to stop the work. Lucian Roach, a Recorder for the Belt party, and Gaylord and his daughter Juliette go to meet the outsiders to get them to allow a restart of the gravity generator construction but also to get his hoard back and regain his status. Whilst travelling around a mud lake, their tractor breaks down and their radio is stolen, leaving us with a cliffhanger until next issue.

I quite liked the premise of this one. The story makes use of a valid environmental issue – with a growing population, what should we do with our litter in the future? Unfortunately, whilst the idea is interesting, the characterisation is poor and the plot unoriginal. In particular, the mayor, Isaac Gaylord, comes across rather like Ralph Richardson’s Boss of Everytown in the film Things to Come – a man of the people, yet ill-mannered and decidedly small-minded. There’s a weak love story begun here too. Reminiscent of an old-school “planetary explorer” story, this was readable, but won’t win any prizes for its telling. 3 out of 5.

To the Pure , by Damon Knight

An appearance of an American author here, who rather like James Blish I seem to know more for his criticism than his fiction. I enjoyed this one. It is a story of human-Antarian relationships, a boy-meets-girl-meets-alien kind of story. When Mr. Nellith, a big bird-like Antarian, arrives to fix the hyper-radio, human technician Jeff Gorman is aggrieved and does everything he can to make the alien’s life horrible. Despite all of Gorman’s boorish antics and general unpleasantness, Nellith completes the job and leaves the planet, taking Gorman’s wife in the process. Although this may sound unreasonable, Gorman is particularly nasty, which gives the reader the feeling that in the end justice was served. Another that is quite readable, though totally predictable. 3 out of 5.

The Squirrel Cage, by Thomas M. Disch

And no sooner do we have one story from this promising young writer, but we have another. I was impressed by Thomas’s debut here in last month’s New Worlds. As for this month, you know the idea that with enough time, monkeys could type out the works of Shakespeare? Well, here’s a slightly different version. This time it is the story of a man named Disch and a typewriter, locked in a lighted room. The man has no idea why he is there – is it an experiment or an observation? – and without knowing what day or time it is, is reduced to copying out or making up dreadful poetry and stories to pass the time. The writer eventually produces the theory that he is in a squirrel cage, where the typing is purely exercise for him, and he is perhaps entertainment in a zoo.

Almost but not quite as good as last month’s effort, I think. Still readable. The trains of thought throughout are logical and there is a faintly amusing tone throughout to give the impression that the writer is in on the joke as well as part of the joke. The attempts at poetry and short stories are deliberately awful. Are we to make fun of the writer or sympathise with him? Not sure – but this confirms my idea last month that Disch is an author to watch. 4 out of 5.

Be Good Sweet Man, by Hilary Bayley

Hilary’s return to fiction after some time as a book reviewer. Whilst the setting is science fiction, this is really a story of sexual politics: on Mars the Conservative and Reform Party has dared to replace its previous candidate with a man! The main idea of the plot is that, after the Third World War, it is felt that it is time to let women run the place – the men made such a mess, after all.

It is amusing to read what can happen with gender stereotypes reversed, although the story makes the mistake, in my opinion, of simply swapping the genders and then letting the women behave like the stereotype of men and presumably the men more like the original stereotype of women. It lacks complexity and depth. 3 out of 5.

Crab Apple Crisis, by George Macbeth (for Martin Bell)

Mike continues his determination to foist poetry upon the readers. I know that there are many who like it, but generally it is not my thing. Having said that, this is a poem of war: of how an accumulation of minor events, namely the stealing of crab-apples, can lead to a major incident. 3 out of 5.

Divine Madness, by Roger Zelazny

Another American big-hitter. Roger’s latest is about a person experiencing time going backwards. The result? Lots of things in reverse – drinking, smoking – and sentences as speech written backwards. The attention is held by knowing that the narrator is about to repeat something that was unpleasant in reverse. It’s a nice idea, though rather impractical, and the reason for this happening is not entirely clear. However, this is pleasingly different from what we’ve seen from Roger so far – a sign of a talent, I think. Not his best, but good. 4 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

The Steel Corkscrew, by Michael Butterworth

Michael is a relatively new talent that we’ve met before with Girl in the May issue of New Worlds. Eight outcasts return to land on a dusty deserted Earth. A strange corkscrew spire is all that remains. Lots of discussion about what it is and where it came from, before the crew find a way in. Death and strange things happen. All seems a bit pointless, although that may be the point. All is death and pain, it seems. 3 out of 5.

The Greatest Car in the World, by Harry Harrison

Just in case you haven’t realised, here’s Harry to remind us that he’s not just an editor and a critic over at SF Impulse, but also a writer. A story for petrol-heads, though you do not have to be one to like it: American Ernest Haroway visits in Italy the Maestro Bellini, the reclusive elderly creator of Bellini sports cars. Haroway returns an item from a Bellini car involved in a previous motor race crash and is given a prototype to drive home in, Bellini’s last ever effort. The ending describes the modifications Haroway will have to make to adapt the car for the US market, in other words to turn the genius of a once-in-a-lifetime car into an inferior mass-production model. Lots of technical talk, which sounds real, although it may not be. 3 out of 5.

Three Days in Summer, by George Collyn

George is now probably a veteran of these here pages, being a regular essay writer, reviewer and story writer at New Worlds. This one’s relatively minor, a re-tread of Orwell’s 1984. A Whitehall romance in a future despotic state, combining bureaucracy and public hangings with a horribly humid Summer. Very similar initially to A Hot Summer’s Day by John Bell in the July issue of Impulse, but this one is perhaps a little more restrained. Like Bell’s story, 3 out of 5.

Prisoners of Paradise, by David Redd

A new writer, I think. Shaamon is an artist who can change form and creates art with light. She finds and merges with a dying creature in a spaceship. The knowledge she experiences she takes back to her Nest mind pool to add to the group consciousness. The group decides to try and find more like this creature, who is clearly human. The purpose of the story seems to be that even in paradise, you should not stop pushing boundaries and acquiring new experiences for the greater good. Whilst this is a debut story, the lyrical writing and vivid imagery suggests that this is a writer with promise. 4 out of 5.

Notes from Nowhere, by J. G. Ballard

No doubt to go with Moorcock’s glowing recommendation in this month’s Editorial, here we have J G’s article "to produce these notes explaining some of his current ideas."

I am of a mind that if an author has to explain himself then I question the validity of their work. Nevertheless, Ballard does try to capture the impossible here. Interesting reading, although I suspect it will leave some readers as confused as ever. Some nice name-checking, though.

Book Reviews

This month James Cawthorn covers a pile of Jack Vance stories now available here in Britain: the stories in The Many Worlds of Magnus Ridolph, and the novels The Languages of Pao, and The Blue World. All are generally liked, although there are some weaker stories in the story collection.

Samuel R. Delany’s Babel-17 also deals with languages, and is highly regarded, which ”only occasionally trips over its hyperbole”.

Frank Herbert, he of Dune fame, has two books reviewed this month. Destination: Void and The Green Brain seem to cover all the bases here – "Journeys also figure prominently… as do giant brains, highly-sexed heroines, religion and characters who endlessly analyse each other’s motives.” And if you didn’t want to read those books before, now you do!

No Letters pages again this month.

Summing up New Worlds

This is another one of those odd issues of New Worlds where I found a lot to like but not to love. Compared with last month’s issue, this is weaker and yet I can’t say I disliked it. Moorcock is using a broad range here and trying to introduce more relatively new writers alongside the established favourites. Will an article by Ballard be enough to persuade readers to buy? Or a story from promising new writer Disch? Not sure.

The Second Issue At Hand

And now to SF Impulse, under the rule of its new editor Harry Harrison.

With the feeling that there’s a sign saying “Under New Management” hanging off it, Harry in his Editorial sets out his stall. He acknowledges the work of previous editor Kyril and present Managing Editor Keith Roberts, promising much, calming troubled waters, and being positive about the future.

Day Million by Frederik Pohl

Another author who is also an editor. This one is a bit odd, as is perhaps befitting the New Wave. A story of genetics and boys not being boys and girls not being girls in a far future. It is also a love story, though Dora is seven feet tall and Don is a cybernetic man. The style is interesting – a story that is written in a conversational style and raises your expectations before contradicting them. I liked it: it doesn’t take itself too seriously, although it is however another reprint, from Rogue Magazine in the US. I guess that this might be where the sexual content was first suited. 4 out of 5.

The Inheritors by Ernest Hill

Ernest’s a New Worlds regular, last seen in the June issue with the not-great Sub-liminal. This time around, we are set in a future where food is processed and much of the work is automated. The overly stressed manager of this world spends most of his time on the verge of a mental breakdown. His attempt to escape the rat race is futile, leading to an inevitable, weak ending. Over-excited and yet predictable, this is another one that seems to be doing little but filling space. 2 out of 5.

Book Review, by Brian W Aldiss

And it would of course not be right to have a Harrison production without some input via Mr Aldiss. Just to make it clear, this is not a story named “Book Review”, but a book review of The Clone by Theodore L Thomas and Kate Wilhelm. Whilst the book under review seems to be nothing new, Aldiss’s review is entertaining , as usual.

Breakdown by Alistair Bevan

Keith Roberts’ nom-de-plume returns with another story set in Bill Frederick’s garage – you know, the one with the demonised car back in the August issue. This time Bill’s mechanical skills are put to the test when he is asked by a local to slow his car down as it has become too fast for him. Investigating further, we discover that the car, having broken down, was tuned up by an on-the-road mechanic to be better than ever before. The twist in the story is that the roadside rescuer is an alien, and Bill has to come to his rescue to fix his alien spaceship. It is all as silly as it sounds, but I liked the pleasingly breezy style to this story.

What is it with all the motor car stories, though? 3 out of 5.

Fantasy and the Nightmare by G. D. Doherty

G. D. Doherty is an academic who has written for the analytical fanzine SF Horizons before.

Here he discusses the point made by Ballard that the most important aspects of SF are really just Fantasy. Doherty unpacks the idea of what Fantasy is – or isn’t – and refers to Ballard, James Blish, Brian Aldiss, as well as non-genre works to make this point. Quite dense stuff that is different in tone and depth to the rest of the work in the magazine, although it is worth comparing to Ballard’s notes in New Worlds.

The Boiler by C. F. Hoffman

Following on from a discussion of Fantasy, we now have a reprint of a classic Fantasy story, first published in 1842. One of those creepy Weird Tales type of stories about Ben Blower, a seaman trapped in a boat’s boiler room during a heavy storm. Its style is quite out of step with the modern material in the magazine, and its olde prose quite jarring in comparison also. Effectively claustrophobic. 3 out of 5.

The Man Who Came Back by Brian Stableford

You might remember Brian for his illuminating attempt to define science fiction in the November 1965 issue of Science Fantasy, or his promising story in the same issue, Beyond Time’s Aegis co-written as “Brian Craig” with Craig A. Mackintosh. This time we look at the idea of identity through William Jason, a space pilot who wakes up in the form of something else. The big debate is whether he is still William or not. Short – I rarely say these things, but actually this one feels like it could do with being longer. 3 out of 5.

The Experiment by Chris Hebron

A new writer. Alfred is a child that like many others has been born with esper powers. The Race Purity League see this as a threat and are determined to destroy the mutants or at least limit them. Scientists try to investigate the matter further. Lots of talk about the importance of the espers' rights and their need to survive follows. Shades of Slan from over 25 years ago, or even John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos from 1957 show that this idea never goes out of fashion. 3 out of 5.

The Unsung Martyrdom of Abel Clough by Robert J. Tilley

This is basically a cowboy western in space. Alien Vat on his first solo Hunt crashes on an alien planet. He hopes to make good his error by capturing some of the human inhabitants of a village and attempts to disguise himself before going to the local bar. He fails. The humans, straight out of the Old West, manage to see through this. A weak ending. 3 out of 5.

Make Room! Make Room! (Part 3 of 3), by Harry Harrison

The last part of this serial novel has a lot to live up to. In this last part New York’s Summer has given way to Winter. Where it was once a heatwave, it is now freezing. Sol, the friend of Police Detective Andy Rusch has broken his hip and is now recuperating in their shared flat, being looked after by Andy’s now-girlfriend Shirl.

The killer of crime boss “Big Mike” O Brien, Billy Chung, is forced to leave the Brooklyn Shipyards where he has been hiding with his vagrant-friend Peter.

The unremitting misery continues, even though there’s a change in the weather. (How do people in New York cope with this?) The story is still bleak. There’s much talk, especially from Sol, of a need for family planning and how uncontrolled births have led to the world as it is today.

I was interested to see if the story caught the murderer in the final part. I’m pleased to say that the ending is quite satisfying, although the demise of the killer is rather quickly wrapped up. It seems that that part of the story is not that important; the setting is most significant. Whilst it is enjoyable, I think that this part was not quite as good as the initial set up or last month’s part, so 4 out of 5. Nevertheless, this has been a notable story and one I’ll remember for a while.

Summing up SF Impulse

The first issue of a new regime, although with assistant editor Keith Roberts still doing much of the work. I can’t see that much of a difference, at least at the moment. Like this month’s New Worlds, there are a lot of stories here, and the issue gains by range if not really in depth. The Harrison finishes fairly well, but there’s a lot of filler here, including reprints. The introduction of more sf criticism is an interesting move, but the use of “classic” stories to fill space a negative one.

Summing up overall

A tougher decision to choose this month. Both issues are fair, and both have gone for range rather than depth. But with nothing particularly strong in New Worlds, though I quite liked Disch’s story, the winner this month for me is, I think, SF Impulse [the Editor's averaging of Mark's star ratings be damned! (ed.)]. It’s not perfect by any means, but it just shows that the magazine is going to keep on fighting – at least for now.

Until the next…

(Join us tomorrow at 8:30 PM (Pacific AND Eastern — two showings) for the next episode of Star Trek!)

Here's the invitation!

![[October 2, 1966] At Heart (November 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/IF-1966-10-Cover-646x372.jpg)

![[September 30, 1966] Return to Base (October 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660930cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 28, 1966] Garbage and Aliens (October 1966 <i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Sept-1966-672x372.jpg)

![[September 22, 1966] True Idols (the Isaac Asimov issue of <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660920cover-659x372.jpg)

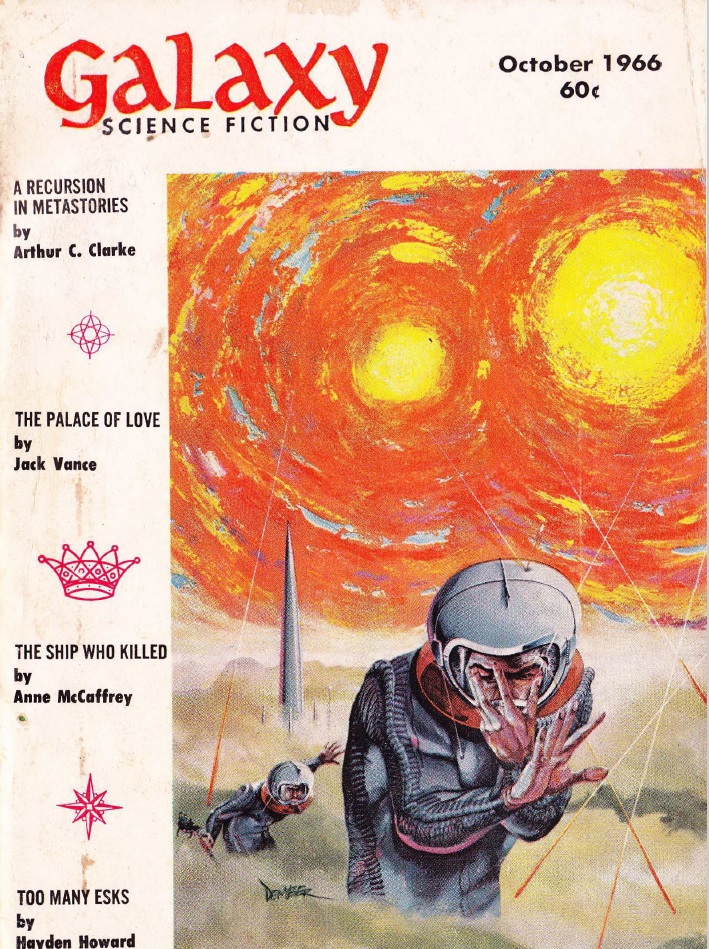

![[September 14, 1966] All the Old Familiar Places (October 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660912cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 8, 1966] The Bare Hardly-Essentials (October 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)</big></b>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/amz-1066-cover-491x372.png)

![[September 4, 1966] British Science Fiction Lives! (Alien Worlds #1 & New Writings in SF #9)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Featured-Image.jpg)

![[September 2, 1966] On the Edge (October 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/IF-1966-10-Cover-662x372.jpg)

![[August 28, 1966] Messiahs and Resignation (<i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, September 1966)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Sept-1966-672x372.jpg)