by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

It’s been a while, but it’s good to be back.

Something I suspect Editor Mike Moorcock has been saying too, because since I last wrote THINGS HAVE HAPPENED.

Quick recap, then. You might remember that last issue I said that newsagents W. H. Smith and Sons, Britain’s biggest newspaper and magazine vendor, in collaboration with John Menzies, refused to distribute the March issue of the magazine on the grounds of ‘obscenity and libel’, and that the national newspapers here once they got hold of the story brought it to national attention?

Well, it got further. In May, questions about the magazine, as a consequence of being partly paid for by the national Arts Council, were raised in the House of Commons, no less.

With national coverage in the House of Commons a Tory asked a question of Jennie Lee, the Minister for the Arts, asking why public money was being used in this manner (since the Arts Council is funded by taxes).

So New Worlds is now part of the records of British government, forever!

So New Worlds is now part of the records of British government, forever!

From what I understand Miss Lee gave a spirited riposte to the criticism, but what impact this will have on the magazine, I must admit that I don’t know. I’m lucky in that I get my copy through a subscription, but as most copies are purchased by casual buyers off the shelves in the newsagents this can only be bad – especially as I’ve said in the past that sales have recently declined, and Moorcock is desperate to increase revenue. It also means that readers are unlikely to see a copy at their local library.

On to this month’s issue.

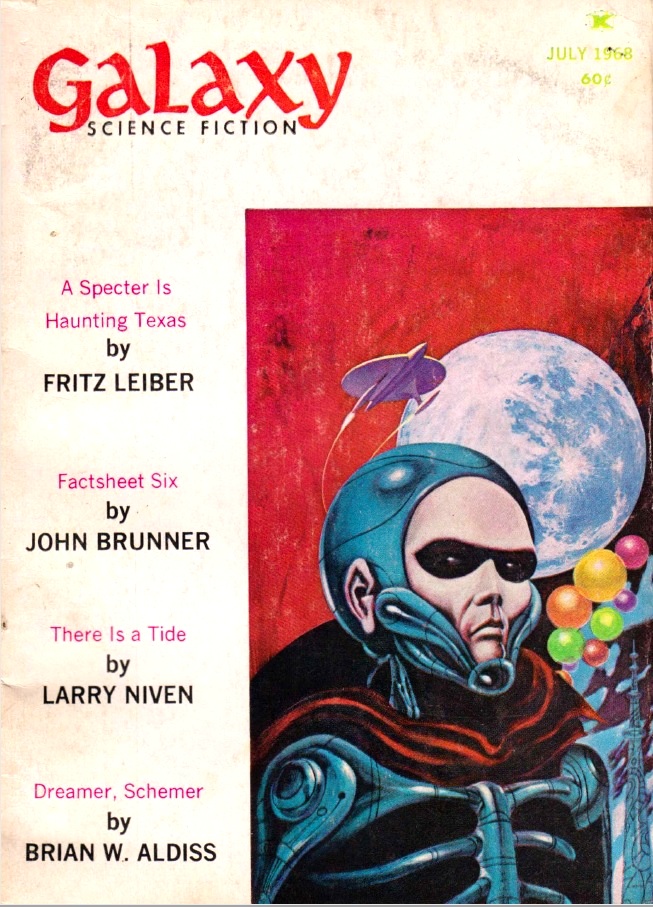

Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

These covers seem to have regressed, haven’t they? This is the latest that to me echoes the bad old days at the end of the Carnell era, when there was just no money for artwork. Sound familiar? If you’re looking to grab attention, this isn’t it.

Lead in by The Publishers

Some changes here too. Editor Mike Moorcock has brought readers (those of us who are left, anyway) up to date with what has been happening in the Lead In, even if some kind of strange time warp has happened as the Editor claims that his comments were made “last month” and not actually in the April issue. Readers with a good memory and less impacted by this may remember what Moorcock said back in April, when more pages and pictures in colour were promised – clearly now that isn’t going to happen.

The rest is just the usual descriptions of the authors and their explanations of their stories, for those of us too unintelligent to work it out for ourselves.

Scream by Giles Gordon

Giles’s second published effort, after his story Line-Up on the Shore in the December 1967 issue of New Worlds .

Scream is another of those Ballardian-like stories divided into sections and often filled with stream of consciousness adjectives so beloved of New Worlds of late. It describes the effects of a single scream – in a city, on the people who hear it. Some panic and run whilst others are just confused. Result – a tale that feels like it wants to be seen as new, but really isn’t. There are lots of pseudo-meaningful phrases clumped together in a manner it would be wrong of me to describe as a story, emphasised by the point that the text has printed prose running at different angles around the page, which does little to endear the story to me as a reader.

Scream can be summed up as being full of allegorical symbolism, combined with language determined to grab your attention but to increasingly meaningless effect. It is memorable, but not always for good reasons. I hope I never have to come across the words “love juice” in New Worlds again. 2 out of 5.

Drake-Man Route by Brian W. Aldiss

And now on to the return of another regular and much-loved writer. Bad news, though – Drake-Man Route is another Charteris story. These have had diminishing returns for me since the first, Just Passing Through in the February 1967 issue of SF Impulse. And this one soon degenerates into the gobbledegook last seen in Auto-Ancestral Fracture in the December 1967 issue. Charteris has returned to England from Europe and travels north from London to try and communicate what he has seen. Lots of strange events occur as a result, with Charteris travelling with people who lapse into gibberish as a consequence of PCA Bombs in the Acid War, and meeting Brasher, the leader of the People of the new Proceed, the religious group created after the war. There are details on how Brasher got to this point, before they all drive off into an inconclusive ending marked by poetry, song lyrics and, guess what – more text running in unusual directions around the page.

Some may like these stories for their use of imaginative language, strange poetry, and drug-related symbolism. Others (like me) may be less impressed. Almost makes me rather read Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land instead, of which I’m really not a fan. I really hope there’s not many more of these. 2 out of 5.

Bug Jack Barron (Part 5 of 6) by Norman Spinrad

This one seems to have gone on forever. I now realise that with next issue being the final part I have been reading this story for over six months. Such an extended space of time does not help keeping up with this, although the summary of what has gone before helps, even if it now extends over a whole page in small print.

Things take a turn this issue, finally! After what feels like months of incessant ranty dialogue, Jack is contacted by the wife of Teddy Hennering, the Senator who co-founded the Freezer Bill with Howards and who Jack took to task live on air back in the first part of this story. He has been killed because he was about to reveal something about the Foundation – murdered by Howards, according to the wife. Jack dismisses the call as one borne of hysteria, but then the next day she is killed by a hit-and-run driver.

On Jack’s TV show that night negro Henry George Franklin makes a drunken claim that he had sold his daughter to a white man for $50 000. After the show Howards demands that Franklin is kept off the air and threatens to kill Barron if he doesn’t. Barron’s response? Feeling that Howards is somehow involved, he goes to visit Franklin in the Mississippi.

After four parts of lengthy dialogue and debate we finally get something happening. Spinrad moves the plot along and clears the decks for presumably what will be a final showdown between Barron and Howards in the final part. For that reason, it is better, but still feels weary. 3 out of 5.

Instructions for Visiting Earth by Christopher Logue

Poetry time. This one is about how aliens should blend into the background by being predictable and conformist, but at the same time tells us of the things that make humans human. Despite it being rather unmemorable poetry, this one gains points for being both pleasingly short and – gasp! – understandable. 3 out of 5.

Plastitutes by John Sladek

Remember last month’s New Forms, Sladek’s story of a form that wasn’t a form? Here, Sladek’s at it again, producing a comic strip-style story that reminded me of the Charles Platt cut-up diatribes we’ve seen in recent issues. I quite liked the Platt versions, this one less so, a tale of satirical nonsense involving IBM, pictures of car parts and fake conversations between idealised figures of manhood and womanhood. Difficult to describe – this has to be seen rather than understood. The McLuhan is strong in this one. 3 out of 5.

Methapyrilene Hydrochloride Sometimes Helps by Carol Emshwiller

The latest in a number of recent stories by Carol in New Worlds, who seems to be blazing a trail for telling odd stories from a female perspective. This time it is a dialogue given by a woman/robot/alien (who knows?) about the strange relationship she has with a male Doctor and his daughter. Lots of biological comments and various body parts are involved. As predicted, it is odd, and I’m not sure I get it. 2 out of 5.

Two Voices by D. M. Thomas

I approached this one with caution after the awful “Head Rape” poem of the March issue. Thankfully this one is not quite as traumatic, although much longer than what we normally get – more of a poetic essay than a poem, involving two different perspectives. Unsurprisingly the story involves sex, birth and death (I think.) The accompanying artwork feels like something out of a psychedelic-Beatles creation. So – marks for style, ambition and intelligence, if not for literary quality. 3 out of 5.

The Definition by Bob Marsden

Another story obsessed with sex, though using deliberately florid and shocking language in an attempt to shock. It tells of the night (and the morning) after a rock concert party, with the associated sex, drugs and rock and roll. I suspect it is meant to be satirical, but rather than being innovative and interesting, this was just silly – the point where a drunken character is hit on the head with “an autopenis” was the limit for me. 2 out of 5.

A Landscape of Shallows by Christopher Finch

Art by Francois Vasseur

A tale that in its dry observations and depiction of its settings, not to mention in its detailed descriptions of vehicles, feels like a Ballard-style tale. Set in an Arabian country, Drover works for Delta Studios, who create advertising campaigns created by computer that use all senses – sight, hearing, taste and smell. There he meets Amaryllis, who tests the machine used to create Drover’s experiences, and this leads to a one-night stand, although the focus of the story seems to be on Drover’s occupation.

I must admit that for much of this story I couldn’t work out what was real and what was imagined by Drover as he relates his dream-like descriptions back. I suspect that this uncertainty may be the point of the plot. Some interesting ideas though – as well as the idea of fully immersive art, I quite liked the idea of the car radio that adapts to the user and their moods. Despite its relatively linear structure, I found I was enjoying this more than I thought I would, probably because it followed the needlessly poetic and pseudo-intellectual style of the previous stories. Still Ballard-light, though. It actually reminded me a little of the last Langdon Jones story published here, in its determination to change form between sections. 4 out of 5.

The Circular Railway by John Calder

As the Lead-In tells us, John’s last work here was Signals in the September 1966 issue. The Circular Railway is a story that on the surface does little more than describe a dreamlike journey taken on a railway, in poetic tones. But of course, being allegorical, it probably means more than it suggests. Overall, it makes me think of a typical train journey for me – one that is putting me to sleep. 3 out of 5.

Book Reviews – Dr. Moreau and the Utopians by C. C. Shackleton

No poetry reviews this month – instead, C. C. Shackleton (also known as Brian Aldiss) points out that the writings of H. G. Wells seem to be back in favour once more, and then addresses the idea that H. G. Wells has often been considered as an optimist. This may be surprising when you consider Wells’ works such as The Island of Dr, Moreau, which told of the horrors created by genetic manipulation.

Nevertheless, Shackleton eventually gets to the point of the review – that a book by Mark R. Hillegas entitled The Future As Nightmare looks at Wells’s ideas of utopia and how such ideas are regarded by his contemporaries and successors. Annoyingly, just as it seems to be getting to a point, the review is then truncated, to be continued next issue (optimistically).

An interesting article – but then as Aldiss/Shackleton is also a huge admirer of H. G. Wells, I would expect nothing less.

Summing up New Worlds

Clearly the long lay-off has given the New Worlds team chance to catch up on some poetry. As we had none in the last issue, this month we have two. I suspect that this may be new Associate Editor James Sallis’s fault.

We also seem to have had a new typewriter installed in the printing works, as we have not just one but two stories that mess around with

T

H

E

TEXT a BiT.

Aldiss has been guilty of such experimental prose before, whilst I think back to Alfred Bester’s The Demolished Man and The Stars My Destination back in the 1950’s.

I always feel that such textual acrobatics are more about style than substance, sadly. It’s not really new, nor really clever. And whilst I can appreciate the idea of writers playing with form, is it really necessary to have two doing the same thing in the same issue? It feels a little like desperation to me. The fact that, as much as Brian has done to retrieve New Worlds from the brink of bankruptcy, his Charteris stories do little or nothing for me doesn’t help.

But then I could say that about some of the other stories in this issue as well. The issue generally is filled with material that is odd, unpleasant, or both!

Most of all, this issue feels again like New Worlds is in a holding pattern. There are lots of middling or low scores, suggesting that this issue feels a bit like it is treading water. At its worst this feels like an issue that actually seems desperate, where there’s a need to publish but it is an issue made up of what’s available, rather than the best that New Worlds can be. There’s nothing here that I found particularly memorable, and the emphasis on trying to shock the readers seems to have diminishing returns – for me, at least.

This is a little worrying. I expect to find at least one story or article or review each issue to keep my interest and my subscription paid. This issue didn’t really have anything, although it could be argued that that in itself is a point of discussion.

As frustrating as this issue was, I know that I should be grateful to see anything this month – it is good to have New Worlds back again, even if who knows for how long.

I did not notice an advertisment for the next issue, worryingly.

Nevertheless, until next time – whenever that is!

A political cartoon from after the First World War.

A political cartoon from after the First World War. Sam Nujoma (r.), President of SWAPO, shakes hands with Mostafa Rateb Abdel-Wahab, President of the Council for Namibia

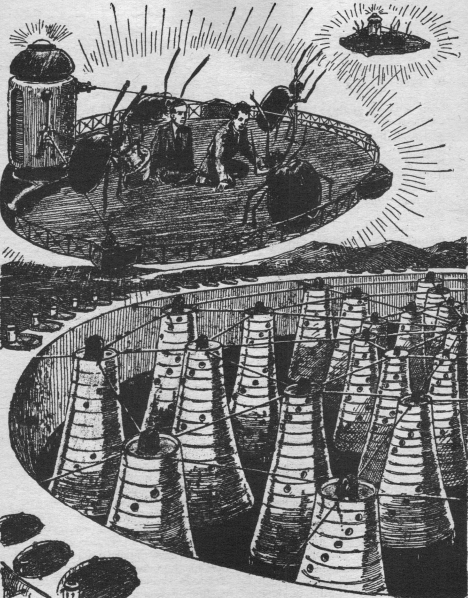

Sam Nujoma (r.), President of SWAPO, shakes hands with Mostafa Rateb Abdel-Wahab, President of the Council for Namibia Supposedly for Rogue Star, which doesn’t have a starship crash. Or this many characters. Art by Chaffee

Supposedly for Rogue Star, which doesn’t have a starship crash. Or this many characters. Art by Chaffee

![[July 2, 1968] What’s the Point? (August 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/IF-1968-08-Cover-505x372.jpg)

![[June 30, 1968] Hawk among the sparrows (July 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680630cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 26, 1968] To far off lands (July 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680620cover-451x372.jpg)

![[June 18, 1968] I Just Read It for the Stories (February-June 1968 <i>Playboy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680618_PBCvrMarch-672x372.png)

![[June 16, 1968] More Scandal! <i>New Worlds</i>, July 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/New-Worldsa-July-68-672x372.jpg)

So New Worlds is now part of the records of British government, forever!

So New Worlds is now part of the records of British government, forever! Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

![[June 10, 1968] Froth and Frippery (July 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680610cover-653x372.jpg)

![[June 6, 1968] The Stalemate Continues (July 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/amz-0768-cover-496x372.png)

![[June 2, 1968] Necessary Evils (July 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IF-1968-07-Cover-543x372.jpg)

The Baltimore Nine shortly after their arrest. Fr. Philip Berrigan is 2nd from the left in the back row.

The Baltimore Nine shortly after their arrest. Fr. Philip Berrigan is 2nd from the left in the back row.

Abbott and his men are the first to reach the Sleeper’s chamber. Art by Gray Morrow

Abbott and his men are the first to reach the Sleeper’s chamber. Art by Gray Morrow![[May 31, 1968] Euler's Issue (June 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/680531cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 20, 1968] Dying, deflating, and deorbiting (June 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/680520cover-665x372.jpg)