by Rosemary Benton

Horror meets SF

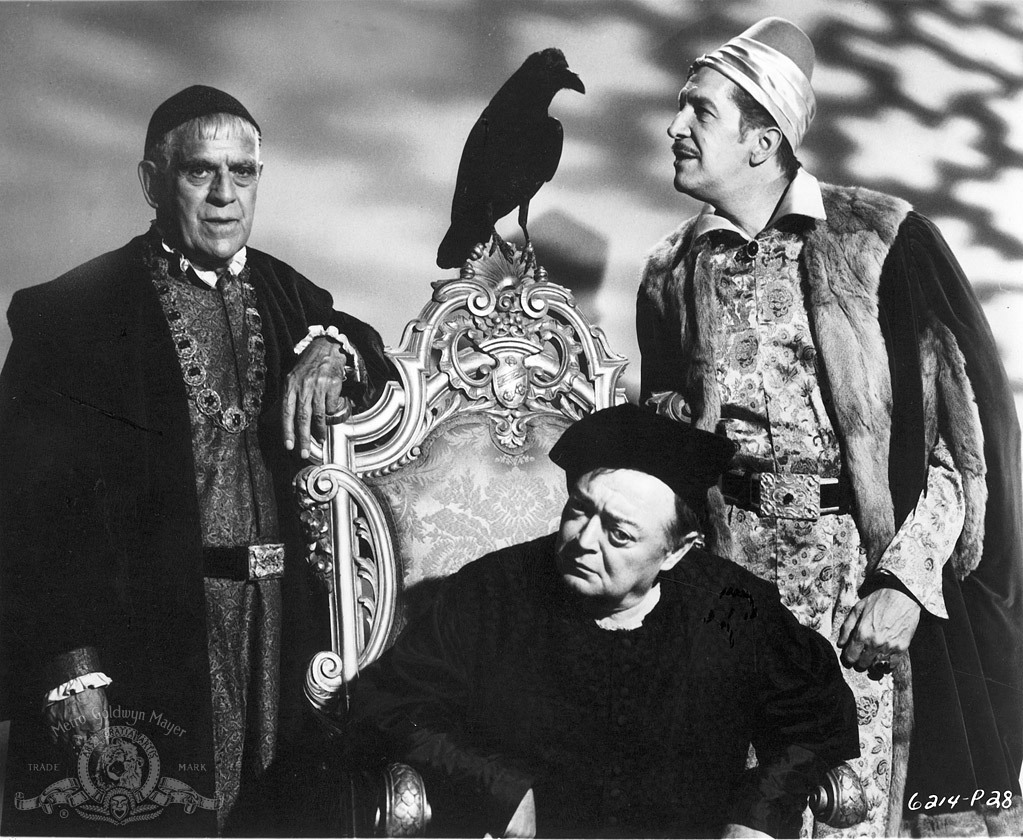

As creators and Hollywood producers have found, horror is a versatile complementary genre that has been instrumental to the fear factor within thrillers, the stark human experience in film noir, and the complex depth of character behind a compelling villain. Recently, the genre has been going through a bit of a self-imposed revolution as it moves away from late 1800s and early 1900s stock-stories to pair off with 1950s science fiction literature such as John Wyndham's book The Day of the Triffids. Comedy has increasingly been a partnered with horror, as in The Tingler (1959), the self-aware movie The Comedy of Terrors (January 1964), and the upcoming freaky-family sitcom The Addams Family.

Those who have made a name for themselves as character actors within horror (Boris Karloff, Peter Lorre, Christopher Lee, Bela Lugosi, Peter Cushing, and of course Vincent Price) are more and more finding themselves in roles that are written to be the very embodiments of the characters they were initially typecast as. While they take on these roles with flair and aplomb, seeing them act outside of their comfortable and accommodating niches is an exciting opportunity for their fans. This month the debonair gentleman-villain/tragic aristocrat character actor Vincent Price was given the opportunity to showcase his acting talent in the newly released film, The Last Man on Earth, a film that promised to be a stark departure from his previous roles.

Based on the 1954 novel I Am Legend by Richard Matheson, The Last Man on Earth follows the depressing life of Robert Morgan (played by Vincent Price) after a deadly plague sweeps the planet, turning infected people and animals into shambling, blood thirsty vampire ghouls. Even with the book's heavy reliance on internal dialogue and the writing's somewhat disjointed flow, a brilliant movie adaptation of I Am Legend would be entirely possible in the hands of a succinct screenwriter, a brooding leading actor, and a director capable of bringing severe emotional distress to the screen. Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of the talented team behind Last Man, none of these elements quite linked up with one another. The result is severely disappointing.

What Happened?

Robert Morgan was once a scientist working to find a cure to the plague creeping across the globe. But when the disease took his neighbors, his fellow scientists, then his child and finally his wife, Robert found himself alone with the terrible burden of quite possibly being the last human being alive.

Boarding up his house and festooning it with garlic strands, crosses and mirrors, Robert whiles away his evenings making stakes and farming garlic as the zombie-like vampires beat away at the outside of his house. Alcohol, records, books and home videos are some comfort, but also stand as constant reminders of the civilization he is now bereft of. During the day when the vampires seek shelter from the sun Morgan methodically sweeps the area to hunt them down, stake them, load them into his station wagon and drive the bodies out to an ever burning plague pit.

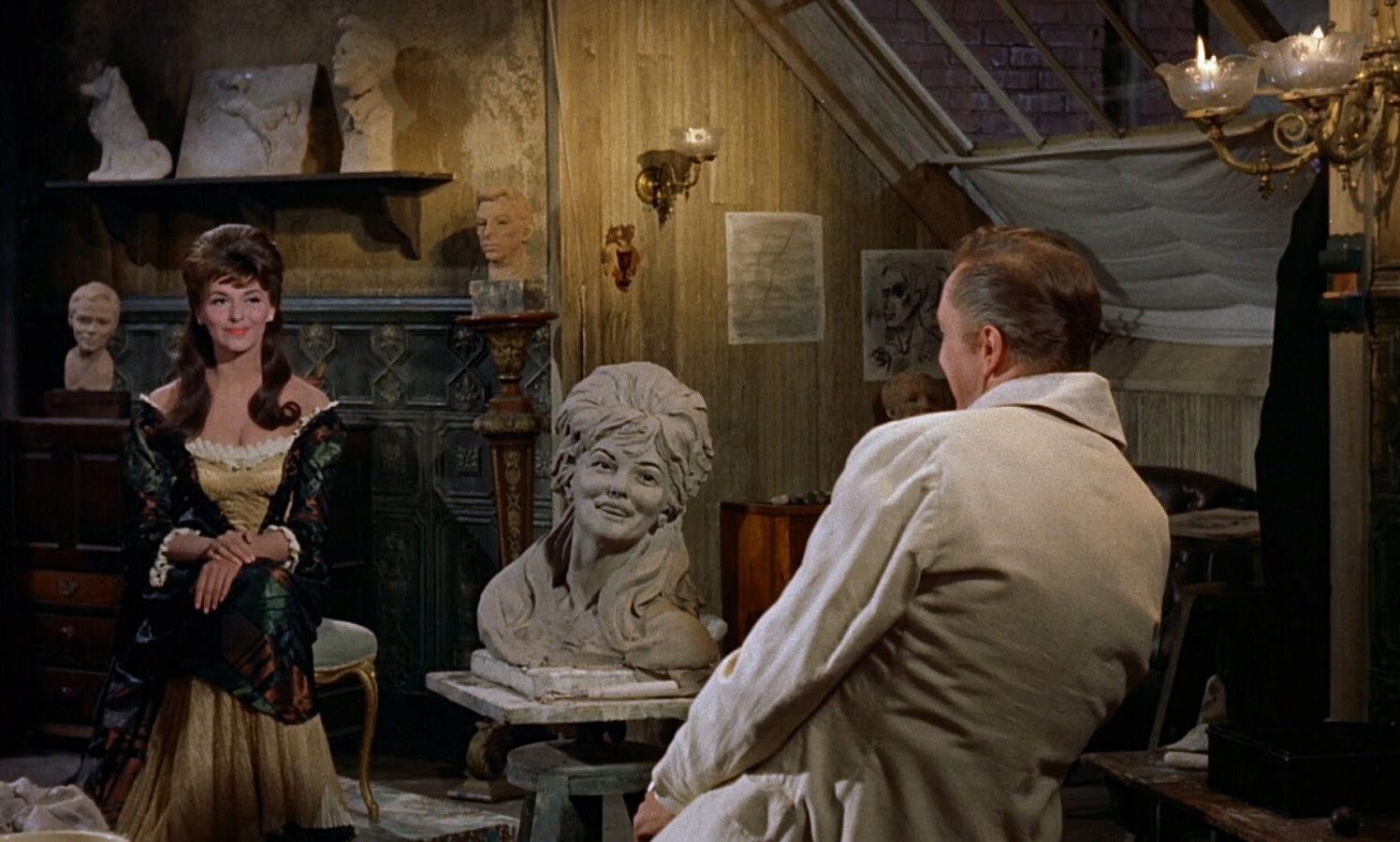

After three years of this grim routine Robert happens to come across a woman named Ruth Collins (played by Franca Bettoia) who is out walking in the sunlight. He chases her down and brings her back to his home. Robert soon deduces that she is one of the infected, but comes to find out that the vampire disease has been contained with a drug that must be taken regularly lest the victim lose their sanity. She tells him that she was sent to spy on him by order of the new society of vampires she belongs to. The group intends to find a way to take revenge on Robert for killing many of their number as they hid from the sun. She explains to him that he is the new monster in this world, killing during the day while the new norm sleep.

After a short altercation Ruth becomes unconscious. While she is out Robert filters Ruth's blood through his own body via a makeshift dialysis setup, effectively curing her of the vampirism. But Robert's discovery of a cure is too little too late. As Ruth and Robert come to realize the miracle that has taken place a vampire breaks into the house and bites Ruth, effectively ending her brief return to full humanity. Just then black vans full of heavily armed vampires roll up and begin to slaughter the feral ghouls stalking around Robert's property. Their mission is to exterminate Robert, just as he has been doing to any sleeping vampires he has come across. Fleeing the house and running into a church, Robert is pursued and fatally wounded. Spitting venom and insults at the vampires, Robert crumples on the steps to the pulpit and dies as Ruth looks on. The church begins to fill with worshipers as Ruth walks out. She comforts a crying child saying that there is nothing to be afraid of anymore, and then the film fades to black.

What went wrong

To preface my oncoming analysis of The Last Man on Earth, I wholeheartedly believe that a movie adaptation of a book is not obligated to be a carbon copy of its source material. Movies such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) and The Most Dangerous Game (1932) prove this well, both of which were wonderful films even though the creators took liberties with the characters, scenes, and atmosphere of the literature they were based on. That being said, given what the writers of Last Man chose to keep from Matheson's novel and what they chose to tweak, the movie just doesn't come across as raw, desperate and angry as it should be. The blame lies primarily in the music, and as much as it pains me to say this, in the casting of Vincent Price as Robert Morgan.

Upon hearing the opening trills of the music, heralding the credits to begin rolling onto the screen, I felt something was wrong. The music blares loudly over the words with a cliché cacophony of horns and violin before switching to a melodramatic lilting tune, then back to clashing force full of a powerful energy completely at odds with the fragile looking, depressed Vincent Price mulling around his boarded up home. The musical scoring doesn't get any better from there. At times when the audience is supposed to feel the tedium of Robert Morgan's existence there is music that makes you feel as if his daily routine is full of exciting danger. In actuality it is full of mundane horror as he forces himself awake day after day with only the acts of eating, repairing his home, and exterminating the sleeping vampires (men and women alike) to keep his mind occupied.

Most insultingly the entrance of Franca Bettoia's character brings with it a strange romantic subplot that seems to come out of the blue with little buildup and conflicting sincerity. The interplay between Price and Bettoia takes on a very jarring fast succession of shoulder shaking, menacing staring, hysterics and hugging. During all of this the score flips wildly between lovely crescendos and stricken horns blares and drum rolls to show betrayal and hurt. It's reminiscent of the sweeping operatic film scoring common of old horror films from Universal Pictures, but feels very out of date for a modern movie that is supposed to be seething with barely repressed despair and scant few moments of actual hope.

Finally, the visual reason the film fails to emote properly comes to rest on the unfortunately sub-par performance of Vincent Price. For a character who is fast coming to believe that he is the last uninfected human on Earth, Price plays the role of Robert Morgan with too much restraint. Robert Morgan is a man with a young family taken by the plague and who lived to see his wife and neighbors come after him from beyond the grave. Such a character should be deeply shaken and depressed as he goes through his remaining days with monotony and acceptance of a life alongside the undead.

Price, however, carries himself like someone who is physically fragile and emotionally cold. His rounded back and stiff-armed walk speak of a man afraid he might break a bone if he moves with more than a shuffle, as opposed to a barely middle-aged man with a heavy burden on his shoulders but a determination to survive. His emotional connection to the other characters in the story seems very distant as well. One could argue that this was a fault of the script, but when the audience sees him chasing the van carrying his still living daughter to the plague pit to be burned, Price is turned away from her body with little effort. He barely struggles at all, and walks away in a daze too easily for a man supposed to be a hysterical, grieving father.

At one point in the story Price's character encounters a ragged dog out in the daylight. His disappointment at learning that a wounded animal he brings home with him is infected is minimal, and in the next scene we see him burying a small bundle with a stake in it. There is little remorse in his posture or expression, even though he is burying the first living creature he has had contact with in three years (before he meets Ruth). Vincent Price just can't do desperation. He can emote long suffering sadness well as is evident in the scene when he visits his wife's tomb and when he is watching home movies and begins to laugh before breaking down into tears, but he just can't seem to nail down what it must be like for a character as raw, desperate and hungry for social contact as Robert Morgan.

The verdict

Sadly, this particular movie is only worthy of a two and a half star rating.

In terms of its competence as a whole, The Last Man on Earth is a solid enough science-fiction/horror movie from directors Sidney Salkow and Ubaldo Ragona, and will likely please the casual movie goer looking for a darker story. But given the material it had to work with in I Am Legend, the movie feels flat. Some films are better when you have read the novel beforehand, but this is not one of them. For those who are die hard fans of Vincent Price I would also avoid seeing this movie as it is hardly his best performance. Instead save your money for the upcoming Roger Corman film The Mask of the Red Death in June.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[March 19, 1964] When Vampires Rule the World (Ubaldo Ragona and Sidney Salkow's <i>The Last Man on Earth</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640319lastmanposter-672x372.jpg)

![[January 30, 1964] Satire or Documentary? (Stanley Kubrik's <i>Dr. Strangelove</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640130strangeloveposter-412x372.jpeg)

![[December 25, 1963] Animating an Epic (Don Chaffey's <i>Jason and the Argonauts</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631225argonautsposter.jpg)

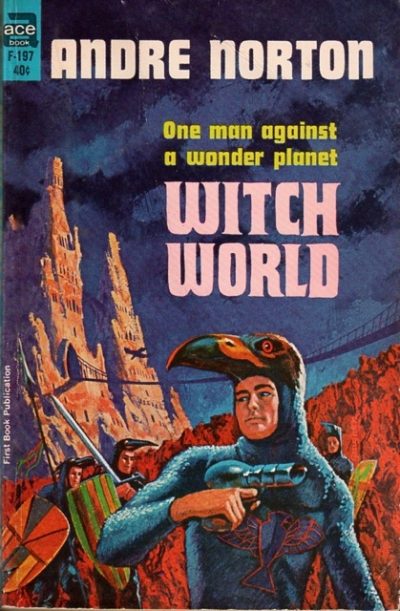

![[October 22, 1963] A Whole New Fantasy (Andre Norton's <i>Witch World</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631022cover-400x372.jpg)

![[September 21, 1963] Old Horror and Modern Women (Robert Wise's <i>The Haunting</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630921hauntingposter-439x372.jpeg)

![[August 23, 1963] Laughing Mushrooms (Ishirō Honda's <i>Matango</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/630823matango-300x372.jpg)