by Gideon Marcus

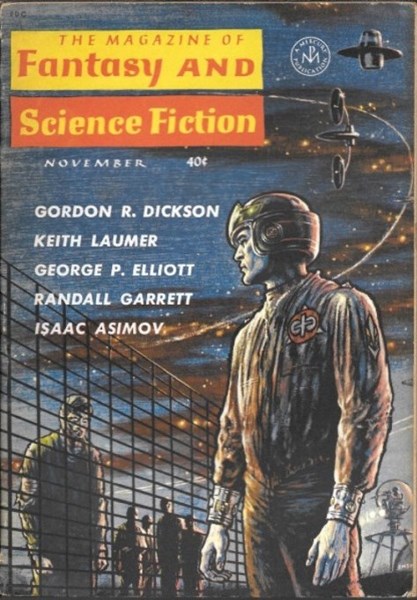

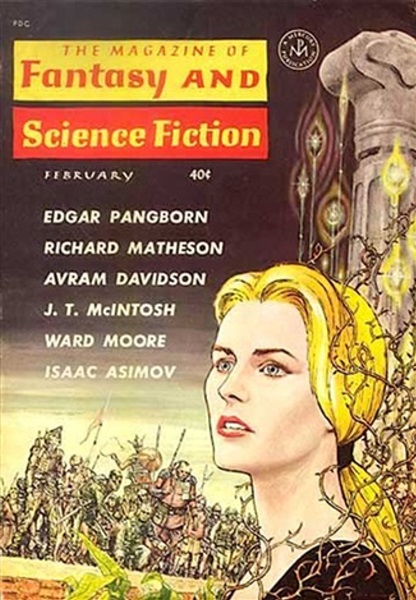

It's been a topsy turvy month: Snow is falling in coastal Los Angeles. Castro's Cuba has been kicked out of the Organization of American States. Elvis is playing a Hawaiian beach bum. So it's in keeping that the latest issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction is, well, uneven.

Luckily, the February 1962 F&SF front-loaded the bad stuff (though it's a bumpy ride clear to the end), so if you can make it through the beginning, you're in for a treat – particularly at the end. But first…

The Garden of Time is the latest from Englishman J. G. Ballard. This tale of an enchanted chateau on the brink of ransack is long on imagery but short on substance (like many pieces in F&SF). You may find it lovely; I found it superfluous. Two stars.

The latest Ferdinand Feghoot (XLVIII) is slightly less worthy than the mean, for what that's worth. A pun that fails to elicit a groan, but merely a tired sigh, is hardly a pun at all.

Avram Davidson has completed his descent into impenetrability. Once a reliable author, somber and profound, his work has been increasingly odd. His latest (The Singular Events Which Occurred in the Hovel on the Alley Off Eye Street) is a parallel universe magical send-up of our present day. I think. He manages to pack more nonsense per square word than ever before, and even Street's paltry 2000 or so words are too many. One star.

One Into Two, by J. T. McIntosh, is something of an improvement: quick and pleasant reading. However, if the best story you can make of a matter transmitter/duplicator is a "perfect crime" piece, you're not thinking too hard. Three stars.

I'd call Walter H. Kerr's Gruesome Discovery at the 242nd St. Feeding Station the least kind of doggerel, but I happen to like canines. I'll just give it one star and leave it at that.

Pirate Island, by Czech Josef Nesvadba, is a reprint from behind the Iron Curtain. I rather enjoyed this bitter tale of a frustrated privateer in the era of Morgan. Something about its lyrical irony appealed. Nothing at all of the stodginess I rather expected from the Eastern Bloc. Four stars.

Jesus Christ seems to be a popular topic this month, He having also made an appearance in Amazing's …And it was Good. In Richard Matheson's The Traveller, a professor journeys back to Golgotha with the intention of simply taking notes, but becomes compelled to save the hapless martyr. It grew on me in retrospect, as much Matheson does. Four stars.

We take a bit of a plunge then, quality-wise. Ward Moore is a long-time veteran of F&SF, and his last story, The Fellow who married the Maxill Girl was a poetic masterpiece. Rebel, a twist on the newly minted "Generation Gap," but with the roles reversed, isn't. Two stars.

Barry Stevens' Window to the Whirled, like Ballard's lead piece, is overwrought and underrealized. It's a hybrid of Clifton's Star Bright (geniuses will themselves cross-wise across time and space) and Jones' The Great Gray Plague (only by leaving boring ol' science behind can one be free), and I really wanted to like it…but I didn't. Two stars.

Even Isaac Asimov's science fact article, Superficially Speaking, about the comparative surface areas of the solar system's celestial bodies, is lackluster this month. Of course, even bland Asimov is pretty good reading. Three stars.

Lewis Turco has a few poetic snippets ostensibly from the mouths of robots in Excerpts from the Latterday Chronicle. They are in English; they are not long. And this ends what I have to say about them. Two stars.

Novice Matthew Grass offers up The Snake in the Closet, a story that presents exactly what's on the tin, and yet is clearly a metaphor for…something, I'm sure. Not a bad first effort, and some may find it poignantly relevant. Three stars.

All of this is but frivolous preamble to the jewel of this issue. Edgar Pangborn is a fellow who has been too long away from the sff digests, and his The Golden Horn is one of those perfect stories, at once gritty and beautiful. Set in post-WW3 America. It is a tale of friendship and betrayal, love and lost innocence, lusterless life and sublime sonority. It's just that good, okay? Five stars.

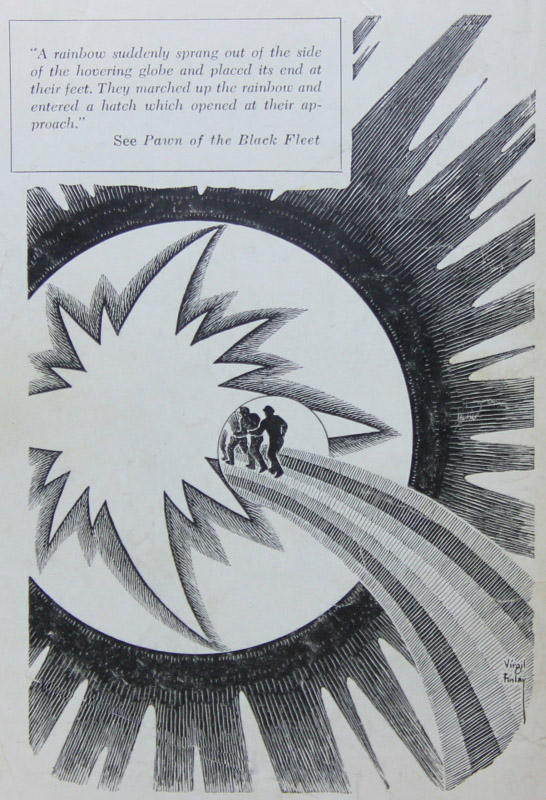

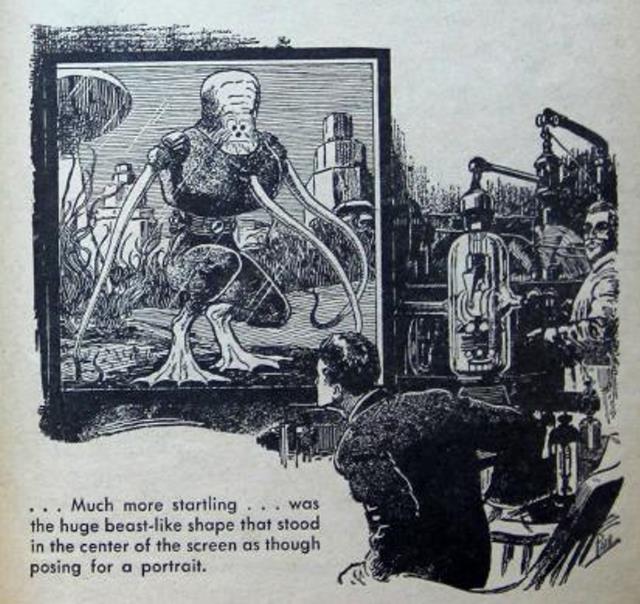

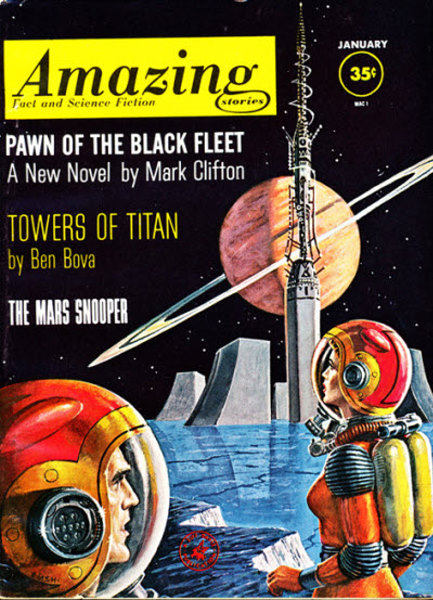

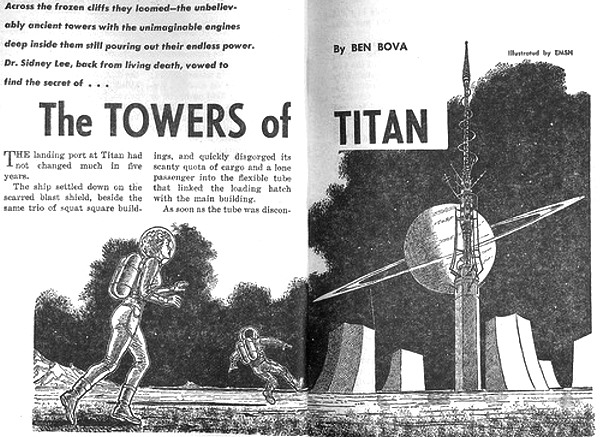

So went February 1962, and F&SF, with its final score of 2.8 stars, ends up tied with Fantastic and Galaxy (though it gets distinction for having the best story). Analog, at 2.1 stars, was the worst. Amazingly, Amazing was the best with 3.3 stars. Some of you may disagree with this judgment (I know Pawn of the Black Fleet was not to everyone's taste) but I stand by John Boston's judgment, both because I must, and because our tastes have proven not to be too different.

Of 33 fiction pieces, just one was woman-penned. A sad state that no doubt contributed to this month's comparative dip on the star-o-meter. However, it looks like Zenna Henderson and Mildred Clingerman will publish next month, so that's something to look forward to.

Stay tuned for the next Ace Double and January's space race round-up!