by Gideon Marcus

and

by Lorelei Marcus

Two years ago, CBS aired the first episode of a new television anthology, one destined for the history books. It was called The Twilight Zone, and it featured science fiction and fantasy themed stories in a most sophisticated fashion. Twilight Zone garnered its creator, Rod Serling, a much deserved Emmy, and if Serling be remembered for nothing else, it's certain he will leave a lasting legacy.

The new season began last month, and though I had high hopes, Serling's creation is starting to feel a little tired. Word through the grapevine is he's a bit storied out, and the episodes that used to flow like water from his pen come a lot more sluggishly. That said, a half hour of Twilight Zone is still better than most hours of other television — and two hours have already been aired this year. Let's take a look, shall we? (Synopsis first, then my commentary followed by the Young Traveler's)

First up is Two, and it's easily my favorite of the new crop. This may well be attributable to it having been written by someone other than Serling – in this case, writer/director Montgomery Pittman. Two features an abandoned urban setting some years after the start of World War Three. A ragged young invader (Elizabeth Montgomery) in a threadbare uniform is scavenging for scraps when she runs across a similarly bedraggled native soldier (Charles Bronson). Though the latter would be quite happy to forget the horrors of war, the Russian woman continues the conflict, repeatedly attacking the American. Ultimately, through kindness and appeal to reason, Bronson convinces Montgomery to give up the fight, her gun, her uniform, and the two head off into the sunset as friends.

There is little dialogue in this episode and no twist. It's just a little post-apocalyptic meet cute. What makes Two work is the sublime cinematography, the deft acting. Bronson has already proven to be a charismatic leading man (q.v. Master of the Air), and Montgomery delivered her virtually wordless role convincingly. Four stars.

Over the past couple of weeks, me and my father have been watching the first few episodes of the new season! The first episode was fairly standard. It was, once again, about life after a nuclear dust-up. There were only two characters, a male and female soldier from opposite sides of the war. The episode was basically just them interacting, and almost no words were spoken. It was exactly what it was trying to be, and I don't really have much else to say about it. You may watch it if you like, but honestly, I would recommend skipping this episode. Two stars.

Serling-penned The Arrival begins compellingly enough: a DC-3 lands at a busy airport with not a single soul or piece of luggage on board. Grant Sheckly, an FAA investigator, is brought in to crack the case. A little past halfway, realizing that none of the pieces are adding up to a coherent whole, Sheckly concludes that the plane is an illusion, the result of some kind of hypnosis. In a tense scene, Sheckly places his hand in the path of the plane's spinning propeller, and the aircraft disappears…along with the rest of the airport crew in the hangar with him!

Sadly, this is the peak of the episode. It turns out that the DC-3 is not some kind of ghost ship, nor is there some sinister purpose behind the apparition. Rather, the plane is a personal demon of Sheckly's; 17 years ago, the plane had disappeared without a trace, and Sheckly's inability to solve the case has haunted him ever since. It's entirely too prosaic an explanation for The Twilight Zone, quite possibly the least satisfying resolution to what started as a most promising episode. Two stars.

The second episode was interesting, at least until the end. It was about a ghost plane with no one on it, and the man who was trying to figure out how it landed by itself. His eventual conclusion was that the plane simply didn't exist, and that turned out to be true. In the end, the man was just crazy, end of story. In my opinion there were a lot of stupid moments that could've easily been avoided that really damaged the story. It was an interesting concept, but not very well carried out. Despite the bad ending, I would recommend watching this one, as there were some interesting parts. Two and a half stars.

The lackluster run continues through The Shelter, another Serling story. A convivial birthday party for a neighborhood doctor is broken up by a bulletin from CONELRAD: unidentified flying objects, believed to be missiles, have been detected, and there is but a matter of minutes to reach safety. The forward-thinking sawbones had built a shelter in his basement, and he quickly repairs there with his family. Then the doctor's friends arrive, each pleading to be let in, but the doctor refuses. Whipped into a panicked frenzy, the neighbors bickeringly debate breaking into the shelter, then fight amongst themselves for the privilege of displacing the doctor's family. Racial slurs are cast against the one Jewish neighbor. Just as the friends batter down the door to the shelter, CONELRAD announces that the UFOs were harmless space debris. The neighbors, shamefaced, attempt to apologize to the doctor, but it is clear that the trappings of civilization cling loosely to them – and to the physician, as well, who refused to share his refuge.

It's not horrible, but this message was done more satisfyingly (and in a less over-the-top fashion) in the first season episode, The Monsters are due on Maple Street. Two stars.

Episode three was fairly straight-forward. It re-explored a common Twilight Zone topic of testing human nature under immense stress and danger. I didn't enjoy it very much, simply because people going crazy and yelling at eachother is not my cup of tea. However, it is still an interesting episode and I recommend you watch it. Three stars.

Last up for now is yet another Serling episode, the Civil War piece, The Passerby. In the wake of Appomattox, a train of bedraggled soldiers trudges past a burned out home toward a final destination. The inhabitant of the house is a fever-ridden widow whose husband died at Gettysburg. She is joined by a maimed Confederate sergeant, who keeps her company as they are visited by several spectral forms in uniform. One is the husband of one of the widow's friends, a man the widow believed had been killed. Then a Union lieutenant whose death the sergeant personally witnessed arrives, asking for water.

The next morning, the sergeant confesses to a deep desire to continue down the road. As the widow pleads for him not to leave, she hears the rich baritone of her husband. He arrives, embracing her, and it is clear now that he, the sergeant, and even the widow are all ghosts of the war dead. Last up the road is Honest Abe, himself, the last casualty of the "Great Unpleasantness."

The first half is a talky muddle, the widow giving an overwrought performance of the kind I might expect in a high school play. Yet, even though it was clear where the story was going (and I have, in fact made fun of shows employing this exact gimmick), I found its resolution somewhat moving. It's nicely scored, too. It deserves two stars, but I'll give it three anyway.

Last week's episode was probably my favorite. It was about a civil war fighter on the long road home who stops, seeking hospitality from a nice young woman. I won't spoil too much (though it looks like my dad may have), but despite the predictable ending, I still enjoyed the episode. The acting was good, the sets, though simple, were attractive, and just overall it had a moody feel. Of course, I highly recommend you watch this one on your own. Three and a half stars.

So ends the first batch of the third season. A mediocre batch, to be sure, though I have to remember that Season Two started badly, too.

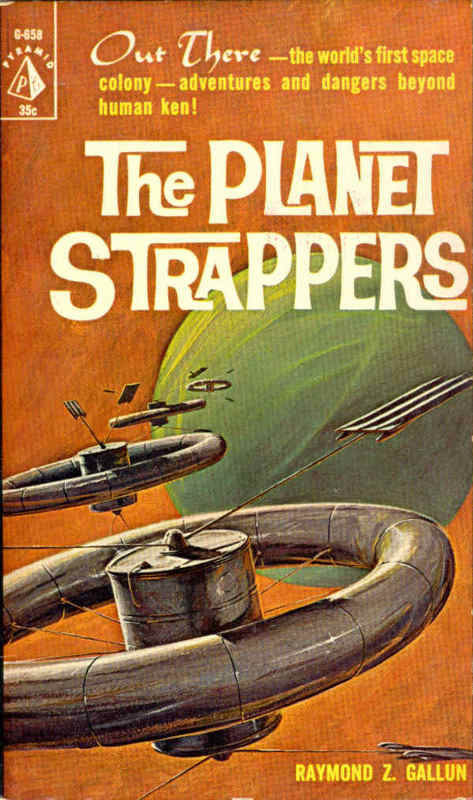

Next week, Galactic Journey will return to the written word. It's a little book called The Planet Strappers, and I think you'll enjoy it (the review, if not the book). In the meantime, as you know, I went to a small convention in Seattle last week. While there, I met a lovely young lady who has since become a fan of this column. She is a fashion model as well as the owner of a clothing store, and she sent me a photo to be included in the column as a kind of advertisement. Please meet Sarah, the Journey's latest Fellow Traveler.