[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Gideon Marcus

The Fall season of television is nearly upon us, so it is appropriate that we pause to reflect on what the Idiot Box has brought us recently. May of last year, Newton Minow, our (relatively) new FCC chief, described television as "The Vast Wasteland." While it may have its moments of education, quality, and even sublimity, he argued, the majority of the stuff you see, network or syndicated, will turn your brain to mush.

I imagine anyone exposing themselves 24 hours a day to every game show, every variety act, every soap opera would make a similar assessment. But what about the selective viewer? The one who rewards only quality with her/his eyeballs? And has there been improvement since Minow made his judgment?

Now, I normally restrict my reviews to things SFnal (science fictional for the non-fan), but over the last year, I've found myself in front of the small screen more hours than I'd normally care to admit. And since a subsection of my followers are, perversely, as interested in my humdrum 1962 life as they are in my analysis, I thought I'd give you insight as to what shows keep the Traveller's tube aglow.

So here are the Galactic Stars, 1961-62 TV edition, covering the television season that ended back in June and has since been in summer reruns. Many of these programs will continue into the Fall season, so consider this a Galactic TV Guide:

Route 66 1960-

Ever since Eisenhower paved the nation with the Interstate Highway system, Route 66, "America's Main Street" has declined in importance. Nevertheless, this national artery will likely always hold a nostalgic hold on our consciousness. It represents a path to anywheresville, an open road with no limits. Where the destination isn't the state of Arizona or Iowa, but rather a state of mind, arrived at only after a long, contemplative journey.

On that road is a Corvette; in that Corvette are Todd Stiles, an erudite Yale ex-pat, and Buzz Murdock, a hard-knocked but soulful kid from New York. Handsome wanderers (especially the latter!) trying to find themselves, in a myriad towns, a plethora of menial jobs. They are Kerouac's Beat Generation set to celluloid, their dialogue filled with poetry and meaning.

There is a formula to the show, albeit one that has lent itself to infinite variation. Each episode features a new town, a new occupation. Usually, a local is in some kind of trouble. Maybe it's physical danger. Sometimes they just need to find where their head is at. There are romances, comedies, hard-hitting dramas…the show runs the gamut. But ever constant is the chemistry of the two leads, their individual charisma (again, particularly Murdock), the lyricism of the scripts, and the backdrop of our vast country.

It can be maudlin, it can even sometimes be dull, but it's usually beautiful. Always worth a watch.

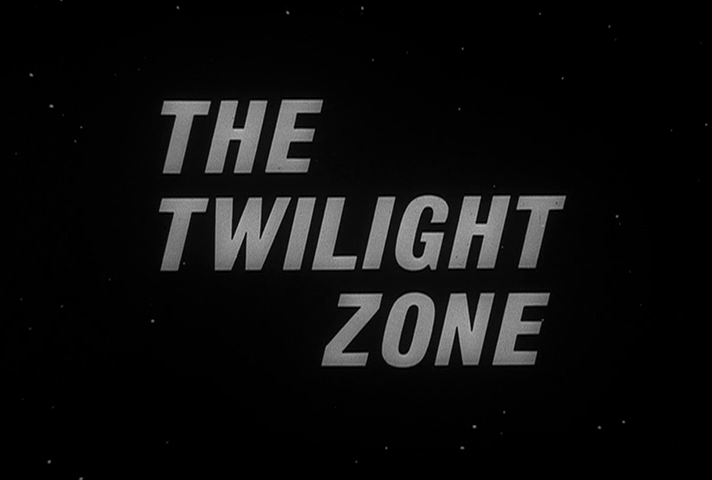

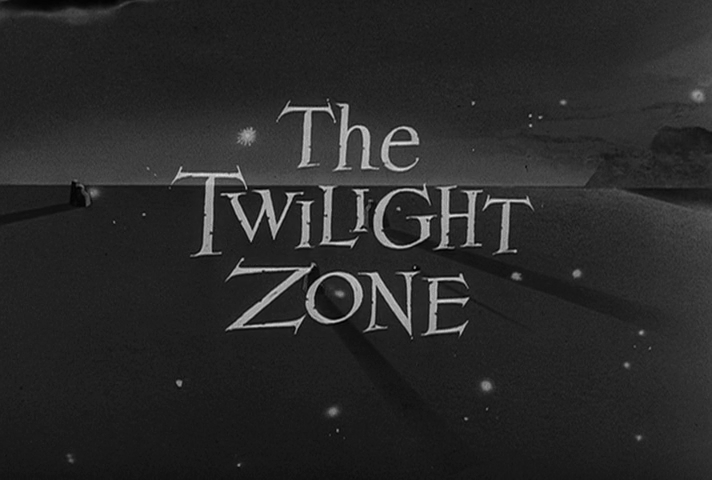

The Twilight Zone 1960-62

Speaking of literary, Rod Serling pinned the quality bar to the ceiling with this sci-fi/fantasy/horror anthology, blowing the doors off inferior (but still appreciated) precursors like Karloff's Thriller and Dahl's Way Out. Of course, this is a show we've covered extensively here at the Journey, but it's still worth noting what an impact Serling's creation had on television. It represents an intersection of innovation, a showcase for writing, acting, cinematography, and scoring. Even at its worst, it was still decent; at its best, there was no equal.

And now it's gone. At the end of the third seaon, Rod decided he was "storied out," and left to take a professorship at Antioch College; producer Buck Houghton went off to work with television production company, Four Stars. There's no sponsor in sight for Season Four.

However, with nearly a hundred episodes in the can, there's no doubt that The Twilight Zone will find its way into syndication, where it can continue to inspire. Perhaps there will be a revival someday. If not, we can at least hope that future shows will strive to top Serling's bar, and television will be the better for it.

The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends 1959-

The Traveler watches cartoons? Don't scoff. Ever since the days of Warner Brothers, there has been animation aimed simultaneously at the young as well as the old. Stuff that combines the rapid slapstick that kids like with witty repartee and sly entendres designed to entertain their parents.

Rocky is a variety show, filled with wacky characters, surprisingly funny puns, and a breakneck pace that will leave you winded. Indifferently animated, it's superbly voice-acted. Whether you're watching the serial antics of the title's flying squirrel and moronic moose, or the Silent Era-inspired tales of Mountie Dudley DooRight, or the often painfully punful Fractured Fairy Tales and Aesop and Son, you will definitely laugh out loud at least once per segment — probably more. It may well be the cleverest thing currently on television.

The Andy Griffith Show 1960-

Now here's one I honestly didn't expect to have on my favorites list. It sounds pretty awful on the face of it: a comedy set in a backwoods town that never quite got out of the 1930s, featuring a drawly sheriff and his bumpkin deputy.

And yet…

There's something gentle and honest about this show. It doesn't rush, it doesn't try too hard to make you laugh, and under Sheriff Andy Taylor's rustic aw-shucks exterior is surprising wisdom and intelligence. Moreover, the interpersonal relationships are mature, healthy ones — even a bit subversively so.

Take, for instance, this (paraphrased) interchange between Andy and his precocious little boy, Opie:

Opie: Pa, I have something to tell you. You promise not to be mad?

Andy: I can't promise that. What is it?

Opie: Well, I put a ball through our neighbor's window the other day. Are you mad?

Andy: No, I'm not mad. Now I have something to tell you, and you promise not to be mad?

Opie: No, pa.

Andy: Well there won't be an allowance until the window's all paid up, do you understand?

Opie: Yes, pa.

No moralizing. No mawkish father-knows-best. Certainly no spankings. Just a discussion between reasonable people. And if you saw my review of the episode where Andy's girlfriend, the town pharmacist, runs for mayor, you know the show can be decidedly pro-feminist, too. Now if they'd only tell where they keep the non-White people…

Other stand-outs include:

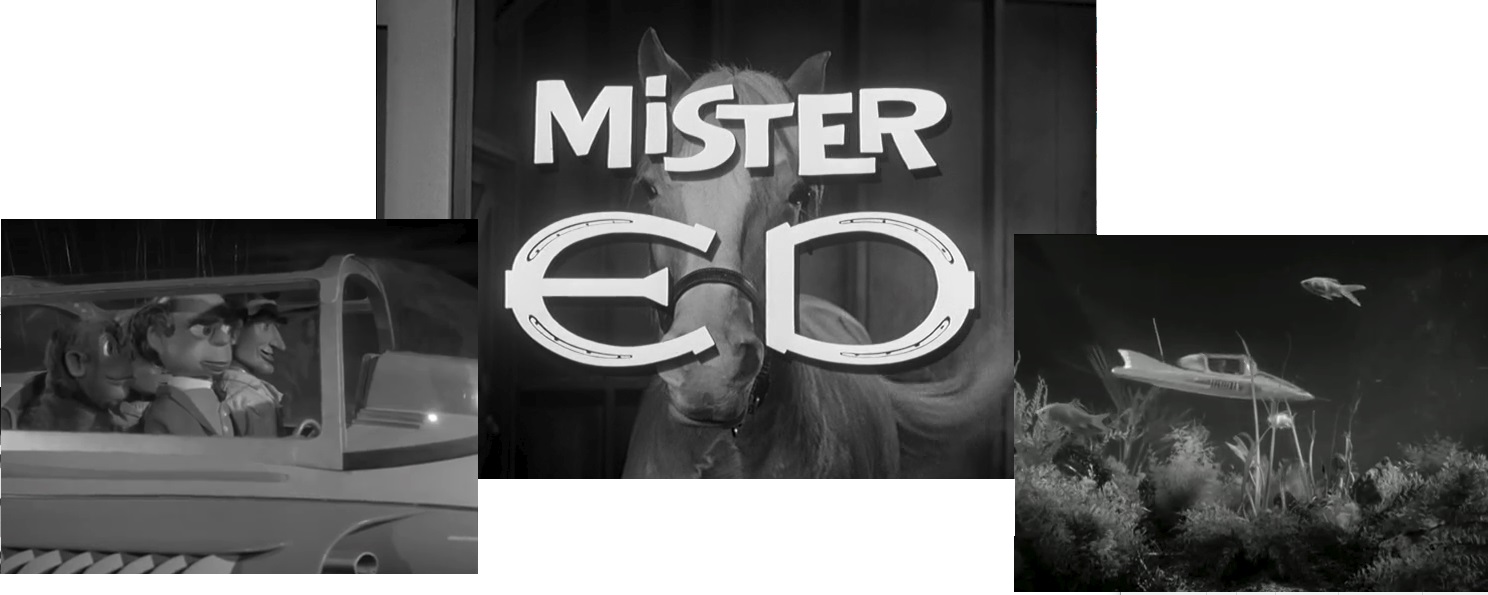

Mr. Ed 1960-: despite being overly rooted in conventional gender roles, one can't ignore Alan Young's charm, the fun of the barbed banter between Young's married neighbors, or the impressive way they make a horse appear to talk.

Supercar 1961-62: this British import is definitely kiddie fare, but it's still fun to watch Mike Mercury and his two scientist associates defeat criminals and triumph over natural disaster. Of course, the acting's a bit wooden…

Then there's the rest…some watchable like Perry Mason (a lawyer/mystery show), The Real McCoys (Okies in Los Angeles), Ozzie and Harriet (dig that Ricky Nelson's singing), and Leave it to Beaver. Others wretched like My Three Sons and the endless cavalcade of Westerns (Gunsmoke, Wagon Train, etc.) Not to mention the Game Shows like Password, To Tell the Truth, and What's My Line.

Hmmm. Maybe Minow's got something there. Still, there's at least ten hours a week of good TV (including the news and occasional Public Television specials like Jazz Casual and last year's documentary on homosexuality, The Rejected).

And if you're watching more than ten hours a week instead of reading that stack of sf books and magazines I've recommended, well…

…you deserve what you get!