by Gideon Marcus

New York. Gateway to America. Home of Broadway, the Empire State Building, Times Square, etc. etc.

Big deal.

This week, my wife and I took a United 707 from LAX to Newark for a mini-vacation. A good friend of ours, whom we met in fandom, lives in Morristown, New Jersey. We stayed in bucolic west New Jersey for a couple of lovely days before hopping the train into Town. You see, I'd never really been to the Big Apple, and my wife had enjoyed the last couple of times. Plus, there was a little convention going on at the time to serve as an anchor. What the hell.

Hell and anchor are right. Lemme tell you, bub — two nights in mid-town, with the bums, the horns, and the smoke, will sour anyone on the place. Maybe the folks here are inured to this constant assault on all of the senses, but for a country boy like me, it warn't no fun. The con was a crummy, disorganized mess, too.

All right. I can see you natives getting your fur up. To your credit, there were some interesting-looking shows on the Great White Way, and my last meal on the island involved some of the tastiest pizza I've ever had, and we managed to meet a clutch of truly excellent people in Manhattan. But we're happy to be back in quiet ol' Morristown for our last day, and ever-so-glad to be heading home tonight.

The experience is not unlike the one I had reading this month's IF Science Fiction. It had a few bright spots, but otherwise was a tough slog. I understand that IF was the low rent sister to Galaxy, offering a bare cent and a half per word and getting what it paid for. When Fred Pohl took over the mag in 1961, he raised the rates for new stories and closed the deal on a bunch of previously rejected bargain stuff to fill the cracks. This issue appears to be made up entirely of the chaff.

The Governor of Glave, by Keith Laumer

Laumer's Retief series is getting long in the tooth. There are only so many stories of a diplomat/super-spy (spy/super-diplomat?) we need. This one was especially tired: the rabble coup the eggheads running a planet dependent on skilled engineers to keep the terraforming plants running. Decent plot but horrible execution. Hint to Laumer — if Retief doesn't feel any need to worry, neither does the reader. Two stars.

The Second-Class Citizen, by Damon Knight

A hand-less dolphin trying to make it in a human world is truly a fish out of water. But what happens when the roles reverse? Damon Knight has returned to fiction writing after a long stint translating European works and doing book reviews. That he's chosen the friendly bottlenose as his subject shouldn't surprise given the success of the recent movie, Flipper (not to mention Clarke's novel, People of the Sea. This particular tale had promise, but it ends too quickly and ham-fistedly. I look forward to better tales from Knight and about dolphins. Three stars.

Muck Man, by Fremont Dodge

Here's a neat concept. After a century of interstellar exploration, humanity has found a dozen inhabitable planets, but none of them are carbon-copies of the Earth. Survival on any of them requires physical modification to deal with the immense gravities or impurities in the atmosphere or dangerous predators. Thus, people who settle these alien worlds become, themselves, aliens. It's very refreshing to find a depiction of a universe that isn't filled with perfectly suitable worlds.

This particular tale involves a fellow who is framed for the theft of a Slider egg, a coruscant treasure found only on Jordan's Planet. Not only is one difficult to obtain, as they are vigorously defended by the fearsome Slider beasts, but they also have a limited lifespan. Asa Graybar was working on a way to keep them alive indefinitely; thus, a put-up job by the Director of Operations of the primary distributor of Slider eggs, who wants to preserve their scarcity and value.

Rather than cool his heels for five years in a conventional prison, Graybar elects to serve a one-year hitch on Jordan's Planet as a Muck Man — a human modified to be a powerful frog-like being. Muck Men are well suited for digging Slider eggs and thriving in the swampy environs. Graybar hopes to use his tenure on the mud planet to continue his research and, perhaps, clear his name. Unfortunately for him, the guy who framed him also comes to Jordan's Planet to ensure Graybar doesn't finish his sentence.

It's a good, vivid story, and it even has a competent female character (heiress to the Slider egg distributor company). However, it's about a third too short, perhaps cut for length like Panshin's Down to the Worlds of Men a few issues back. Moreover, I'm getting tired of there being room for just one woman in any tale, and she only in a position of importance due to breeding. Can't women make it to the top on their own merit? Three stars and hoping for more next time.

Long Day in Court, by Jonathan Brand

This is the first story from "Brand," a university employee operating under a pseudonym. It's an interstellar court of law story, consciously aping the not-at-all futuristic Perry Mason series. The puzzler case of the day: when is beating your spouse both the crime and the punishment?

It's about as amusing as it sounds, though at least it's in English. Two stars.

Glop, Goosh and Gilgamesh, by Theodore Sturgeon

Mr. "90% of everything is crap" proves that the rule applies to its inventor as well as the rest of us mortals. This piece on asphalt is readable, but the guy is phoning in his non-fiction. Get back to fiction, Ted! Two stars.

The Reefs of Space (Part 3 of 3), by Jack Williamson and Frederik Pohl

The first part of this three-part serial introduced us to Steve Ryland, a physicist condemned to life imprisonment for subversive acts against the oppressively harmonious world-state run by a giant computer, The Machine. Ryeland is asked to recreate the reactionless space drive and find the legendary Reefs of Space, free-floating inhabitable structures far beyond the orbit of Pluto. The hope is that this will allow Earth's authorities to find Ron Donderevo, the one terran ever to escape the Machine's regime.

Part Two was almost a standalone tale, chronicling Ryeland's exile to and attempt to escape Heaven, where convicts are doped up and allowed to live a pleasant life — as their organs are harvested one by one until the host can't sustain life anymore. Ryeland fails in the end, but is rescued by Donna Creery, daughter of The Planner, the one person on the planet with authority to change the Machine's programming.

She and Steve escape to the Reefs of Space on the back of the seal-like "starchild," a beast that can travel across light years of vacuum without adverse effects. In their new home, with the aid of the exiled Donderevo, they must prepare to face down dangers both indigenous and Earth-born

Reefs of Space is an odd duck. It's a pair of pulpish book-ends around a virtually unassociated novella. I suspect Parts 1 and 3 were written by Jack Williamson, whose bibliography goes back to the 20s, and Part 2 was done by Fred Pohl. Certainly, the fascinatingly horrific aspects of it feel very Pohlian. In any event, whereas Part 1 barely merited three stars and Part 2 was a surprisingly decent four-star episode, Part 3 is a muddled mess that ends on an abrupt and unsatisfactory note. Plus, of course, it has the mandatory sole female whose high position is earned solely from having had a well-placed father.

Two stars for this section, three stars for the whole story.

A Better Mousetrap, by John Brunner

Last up, a piece from the often (but sadly, not always) excellent Britisher, John Brunner. Hostile aliens have seeded the solar system with asteroid-sized clusters of precious metals that turn out to be ship-destroyers. A very talky piece, as dull as it is nonsensical. Two stars.

***

I won't denigrate this issue too much; IF has always been of widely variable quality, and the good issues make up for the lousy ones. Still, if ever there was an issue to miss, this is it.

You're welcome.

![[October 8, 1963] The Big Lemon (November 1963 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631008cover-474x372.jpg)

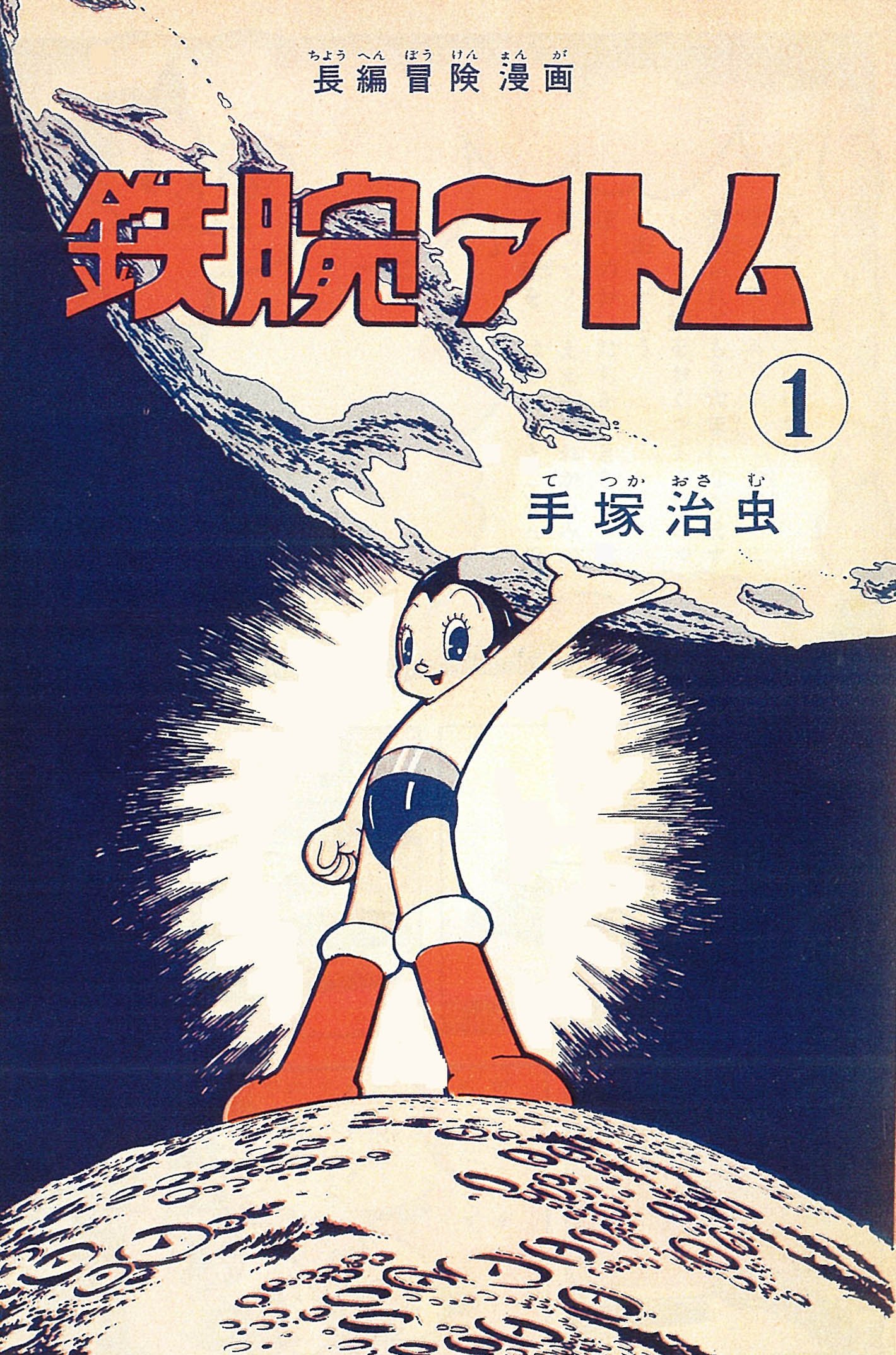

![[October 6, 1963] Birth of a genre (the Japanese cartoon, <i>Astro Boy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631006a.png)

![[October 2, 1963] Worse than it looks (October 1963 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631001cover-649x372.jpg)

![[September 29, 1963] Comrade Wargame (Avalon Hill's <i>Stalingrad</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/631003gamec.jpg)

![[September 25, 1963] The Old School (Margaret St. Clair's <i>Sign of the Labrys</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630925cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 17, 1963] Places of refuge (October 1963 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630917cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 9, 1963] Great Expectations (October 1963 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630909cover-444x372.jpg)

![[September 5, 1963] Oh Brave New World (the 1963 Worldcon)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630902gj-640x372.jpg)

![[Sep. 1, 1963] How to Fail at Writing by not Really Trying (September 1963 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630831cover-672x372.jpg)