[Don't miss your chance to get your copy of Rediscovery: Science Fiction by Women (1958-1963), some of the best science fiction of the Silver Age. If you like the Journey, you'll love this book (and you'll be helping us out, too!)

by Gideon Marcus

Which one is it?

It's election season, and the commercials are already out in force. Maybe it's just my neighborhood, but it seems that LBJ is crowding the airwaves a lot more than Barry Goldwater at this point. One effective ad notes several times the GOP candidate has made mutually contradictory statements and asks "How is a Republican supposed to note on his ballot which Barry he's voting for?"

This piece is a pretty low blow. Make no mistake — there's no way I'm voting for a reactionary this November, but if there's one thing one can say for Barry, he's consistent. I'd rather see some positive messaging. Lord knows LBJ has plenty of successes to run on.

But while Goldwater's split personality may all be a Madison Avenue construct, the schizophrenic nature of IF, Worlds of Science Fiction magazine is very real. IF has always been Galaxy's experimental little sister, the place where the more offbeat stories, the lesser known writers are featured. As a result, it is the more variable mag, with higher highs and lower lows, often within the same issue.

This dual nature is perfectly represented in microcosm with the latest October 1964 issue:

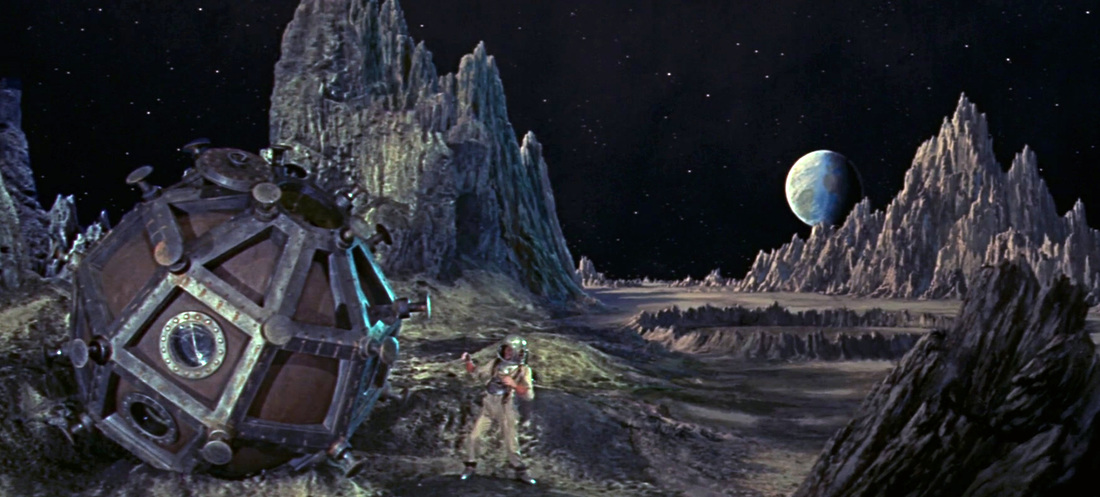

by Paul E. Wenzel (note the obscured "September 1964")

The first thing you might notice is that the issue was clearly intended to have a September date. IF went to a monthly schedule in August (after years as a bi-monthly), but there was trouble at the printers, and things got delayed.

When the issue finally came, it was very much a mixed bag, with trouble appearing right from the start:

The Castle of Light, by Keith Laumer

by Jack Gaughan

Within the pages of IF, Keith Laumer's name is inextricably linked with that of his creation, Retief, that sardonic super-spy in diplomat's clothing. What began as a more tongue-in-cheek version of Harrison's "Stainless Steel Rat" is becoming a tired series of retreads. This particular story involves an invasion by the squamous Groaci, who take legal possession of a planet by landing 50,000 troops in cities abandoned by the native populace during a global religious ceremony. The piece rambles, and the jokes — like the characters — are flatter than usual.

Two stars.

Mad Man, by R. A. Lafferty

The ever-whimsical Lafferty offers up a piece about androids who only attain genius capability when given their daily dose of anger enzyme. Said extraction is provided by a group of human individuals kept thoroughly miserable through poor working conditions and constant aggravation by paid actors. But when one android develops a kinship for her donor, the formerly angry man's heart melts, and his biochemistry becomes useless. Can a replacement be found?

I imagine some will like this story. I found it contrived, cruel, and rather pointless.

Two stars.

Gremmie's Reef, by Hayden Howard

by Virgil Finlay

In which a teenage surfer is delighted to find a perfect wave break on a formerly unpromising beach, thanks to a new reef. Turns out the reef is an alien biological probe, and as might be expected, it's not a friendly one.

The surfing scenes are nicely rendered, but the third-person omniscient viewpoint, the shrieky characters, and the Twilight Zone ending all suggested a young novice of a writer. Imagine my surprise when I checked my notes and found that Hayden Howard has been writing for more than a decade, and I've even covered one of his stories before!

Nice try, but it's another two.

Rescue Mission, by Kit Reed

Science teacher goes on sabbatical to the mountains and finds his cottage besieged with bugs. Turns out they are the servants of Mavna, the alien beauty who resides one cottage over, and she is using the crawlies to send the prof a message: (paraphrased) "Help me fend off these three oafs I'm staying with so I can sacrifice myself for the operation of our interstellar matter transmitter!"

Reed, an author I'm quite fond of, has written exclusively for F&SF since she started half a decade ago. This rather silly piece would fit better in that magazine. That it wasn't published there is not surprising — it's probably the weakest story Reed has produced.

Two stars.

Monster Tracks, by Robert E. Margroff

The last piece of short fiction in the issue is by a genuinely new author, about a boy raised in a post-apocalyptic world ravaged by aliens. They came in "peace", disguised as tourists, bringing gifts and cute pets, but it was all a ploy. Their gifts were bombs, their luggage was guns, and their pets are poison. Our young protagonist is almost taken in by a cute rabbit-like creature before being saved by his savvy uncle.

Not much to this one. Two stars.

Farnham's Freehold (Part 3 of 3), by Robert A. Heinlein

by Jack Gaughan

"Where's the split?" I hear you ask. So far, this issue has been a solid disappointment — how could it be a mixed bag?

Well, editor Fred Pohl got a ringer.

Robert Heinlein is one of the masters of the field with dozens of classic titles to his name. To be sure, his record has been tarnished a bit lately by such substandard works as Stranger in a Strange Land and Podkayne of Mars. Moreover, the first installment of his latest serial, Farnham's Freehold, got off to a stultifying start.

But then it got better. In Part 1, Hubert Farnham and his family (including his house-servant and his side-girlfriend) are whisked thousands of years into the future thanks to a new Russkie bomb. That first bit reads like a cross between a libertarian screed and the Boy Scout Handbook. But in Part 2, we meet the inheritors of the atomically ravaged Earth, the dark-skinned peoples of Africa and India. Hugh and co. are made privileged slaves — except for Joseph, Hugh's servant. His Black skin makes him a de facto member of the ruling caste, and he is afforded the privileges thereof. We learn a lot about the new society, and this section is genuinely interesting.

Part 3 more-or-less ends satisfactorily. It is all about Hugh's attempt to escape his gilded cage along with mistress Barbara and their newly born twin sons. While his first attempts end in failure (and this part is not unlike the middle section of Have Spacesuit Will Travel — thrilling but ultimately pointless), Hugh's kindly master ends up sending him and his family back in time to just before the Bomb goes off, and they have a second chance at life.

It's a thrilling page-turner, and I liked the central message: decadence and depravity have nothing to do with color or national origin. It all boils down to Lord Acton's dictum, "Power corrupts". I especially appreciated that the story recognized the unequal status of Joseph, and does not condemn him for throwing his lot in with America's new rulers. Whatever loyalty Joe had to Hugh, he has found his Earthly paradise — unfair to others, perhaps, but wasn't that just after a lifetime of discrimination? Hugh is dismayed, but not surprised. After all, whatever his libertarian aspirations, he was part of the problem.

I'd give this last part five stars except that the ending is awfully abrupt. All told, I think the novel earns an aggregate of 3.75 stars and, if you can get through the beginning, suggests a return to form of the author.

Making Whole

This latest issue of IF reminds me of Analog a few years back, when the serials were generally good and the other material sub-par (I note with bemusement that while Heinlein's Farnham would fit stylistically in Analog, the editor of said mag would never allow a storyline where the Whites are slaves…) When all is computed, the magazine actually scores above the 3-star middle, which tells you how good the second half is compared to the first.

In any event, the vice of a split-personality magazine is also its virtue: if one can always count on one or more stories not being very good, one can also expect at least one nugget of gold.

And wasn't my entire state founded on the search for such nuggets?

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[September 18, 1964] Split Personality (October 1964 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640918cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 8, 1964] It's War! (The October 1964 <i>Galaxy</i> and the 1964 Hugos)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640908cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 2, 1964] Taking on The Man (September 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640902cover-495x372.jpg)

![[August 31, 1964] Grow old along with me (Brian Aldiss' <i>Greybeard</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640831cover-329x372.jpg)

![[August 21, 1964] The Good News (September 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640821cover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 3, 1964] Running hot and cold (August 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640803cover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 1, 1964] On Target (The Successful Flight of Ranger 7)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640801rangerfirst-672x372.jpg)

![[July 22, 1964] (August 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/640722cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 18, 1964] Dog Day Crop (July's <i>Galactoscope</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/640718covers-672x372.jpg)