by Gideon Marcus

Avram is Gone

Way back in March 1962, Robert Mills left the editorship of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. He turned over the reins to a writer of repute, a man who had published many a story in this and other mags: Avram Davidson.

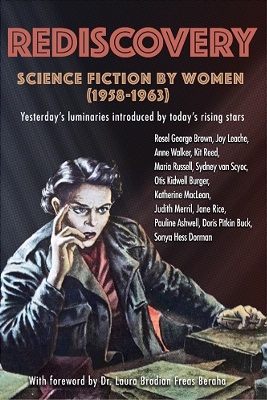

It seemed auspicious — after all, who better for the most literate of SF periodicals than one of the more literary authors in the genre. Instead, the last two and a half years have seen the decline of the once proud magazine continue apace. Certainly, there have been standout stories and even issues (for instance, Kit Reed's To Lift a Ship came out in that first Davidson issue — and I liked it so much, I included it among the fourteen stories in Rediscovery: Science Fiction by Women (1958-1963).

But successes aside, F&SF is mostly a slog these days, filled with uninspired and/or overly self-indulgent stories. The only thing that kept my going was the rumor, confirmed this Summer, that Avram had decided to give up the editorship to focus more on his writing. And so, we have this month's issue, the first in what may be called "The Ferman Era".

Mind you, I'm sure most of the stories were picked by (and certainly submitted to) Davidson, so I don't expect miracles. Join me on the tour of the newest F&SF, and let's see what, if anything, has changed!

by Jack Gaughan

Buffoon, by Edward Wellen

For the most part, Ed Wellen is a mediocre writer, mostly turning in lamentable stuff, occasionally contributing acceptable though not brilliant fare.

This time around, we have the story of an alien who poses as an Aztec at the time of Montezuma. His goal is to become a thrice-sold slave so that he can ultimately be the blood sacrifice made every 52 years. It's all part of an elaborate prank on the indigenes, which is explained in the story's last page.

Despite the seeming light nature of the plot, it's actually rather humorless, a sort of "you are there" piece on the Aztecs. Something one might sell to National Geographic, but with a veneer of SF to make it salable to F&SF. I vacillated between three and two stars; there are some nice turns of writing in there, lots of historical detail, but the whole thing was more tedious than enjoyable. It certainly lacked the charm of the Aztec-themed serial that recently came out on England's Doctor Who.

So, a high two.

The Man with the Speckled Eyes, by R. A. Lafferty

Mr. Lafferty often turns in fun, whimsical tales. But this one, about a mad-eyed fellow who claims to have invented anti-gravity, and who makes disappear the corporate bigwigs who dismiss his claims, doesn't really go anywhere. There're some vivid scenes, some Hitchcock Presents-type horror, and then roll credits.

An ending would have been nice. Two stars.

Plant Galls, by Theodore L. Thomas

Our resident scientific "expert" waxes rhapsodic about stimulating plant galls (think vegetable callouses) with new carbohydrate sprays. Imagine! Like magic, all you have to do is spray a field and you get a giant, cancerous mass of food!

Except Mr. Thomas has forgotten about the second law of thermodynamics — it takes resources to make the spray, doesn't it?

One star.

From Two Universes …, by Doris Pitkin Buck

Of Univacs and Unicorns, which have never met. This poem is the seed for an F&SF-sponsored context: write a story involving both, and you might win $200!

Three stars, I guess.

On the Orphans' Colony, by Kit Reed

Abject loneliness can make one do crazy things. On a hostile world, a young orphan opens the barred doors of his commune, seduced by the maternal sirensong of an otherwise repulsive being. But what horror has he unleashed upon his barracks-mates?

Vivid. Three stars.

Wilderness Year, by Joanna Russ

After the bomb, the sub-surface survivors only go above ground as a rite of passage. Of course, they are given the most advanced devices to ensure their safety.

This is a throwaway joke tale, which the punchline nicely arranged to occur at the top of the page turn where it can be most effective. Certainly not the best Joanna Russ can offer, but not bad.

Three stars.

Somo These Days, by Walter H. Kerr

A poem about sensory deprivation becoming the new, hip rage with all the kids. I imagine it's a commentary on how our teens are plugged into their transistor radios these days, ignoring the outside world.

Silly. Two stars.

A Galaxy at a Time, by Isaac Asimov

Strangely uncompelling piece by Dr. A about close-packed galaxies wracked by mass supernovae. It just didn't grab me like his articles usually do.

Three stars.

Final Exam, by Bryce Walton

A variation on the Last Man/Last Woman cliche. In this one, Last Man doesn't want to commit until a battery of psychological tests determines the potential pair's compatibility.

Forgettable: 2 stars.

The DOCS, by Richard O. Lewis

This would-be Lafferty tale is about a guy whose attainment of multiple doctorates is undercut by his lack of empathy. Facile, with a dumb ending.

Two stars.

The Fatal Eggs, by Mikhail Bulgakov

Ah, but almost half the book is taken up by a gem. The Fatal Eggs is a reprint from the early days of the Soviet Union, an arch piece about a scientist who discovers a mysterious red ray. Said ray not only stimulates the reproduction of animals, but the resulting creatures are fearsome and enormous.

I would not have thought that a 40 year-old piece, translated from Russian, could be so compelling, so colloquially humorous, and delightfully satirical (and thus banned, though our Soviet correspondent, Rita, also read and enjoyed it).

Definitely a four star piece, and I am sad to learn (at the very end) that this is a condensed version! With Bulgakov's story, the journey is as fun as the plot, and I would have enjoyed more comedic scenes of life in 1920s Russia.

Four stars.

All things must pass

Well, we made it. On the one hand, half of this month's issue represents a nadir for the magazine. On the other, The Fatal Eggs is wonderful. On the third hand, it's an aged reprint. Well, any constipation requires time to relieve itself. I'm willing to give Joe Ferman, our new editor (and the owner's son) a chance to prove himself.

How about you?

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[November 19, 1964] Ding Dong (December 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641119cover-425x372.jpg)

![[November 15, 1964] Veteran's Triumph (December 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641115cover-432x372.jpg)

![[November 7, 1964] Landslides and Damp Squibs (December 1964 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641107cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 3, 1964] State of the Art of War(games)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641103rommel-672x372.jpg)

![[October 30, 1964] The Deadly Barrier (November 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641030cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 26, 1964] A revolting set of circumstances (October 1964 Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641026covera-672x372.jpg)

![[October 20, 1964] The Struggle (November 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641020cover-660x372.jpg)

![[Oct. 16, 1964] Three in One (The next leg of the Space Race)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641016voskhod1b.jpg)

![[October 2, 1964] Terrestrial Adventures (October 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641002cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 22, 1964] Fall back! (October 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640922cover-672x372.jpg)