by Victoria Silverwolf

Youth is Wasted on the Young

The children now love luxury; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise. Children are now tyrants, not the servants of their households. They no longer rise when elders enter the room. They contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, cross their legs, and tyrannize their teachers.

— attributed to Socrates

It's no secret that young people are rejecting many of the opinions of their elders these days. That's always been true to some extent, of course. However, with the hippie culture, the civil rights movement, and antiwar protests, all of which mostly involve young adults, the gap between the generations seems wider than ever.

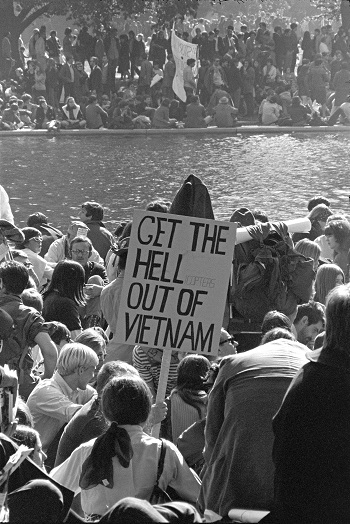

In particular, once heavy bombing of North Vietnam began a couple of years ago (Operation Rolling Thunder, still going on intermittently), college students, led by such organizations as Students for a Democratic Society, started demonstrating against the war. On April 17, 1965, somewhere between fifteen thousand and twenty-five thousand people showed up at the nation's capital, in the largest protest to date.

SDS members and others during the March on Washington, almost exactly two years ago.

There have been many other protests since then, both in the United States and other nations. I don't mean to imply that these demonstrations consist entirely of young people, but they do seem to make up the majority of peace activists.

Just yesterday, thousands appeared at massive protests against the conflict in Vietnam in major cities across the United States. In New York City, well over one hundred young men burned their draft cards, followed by a speech by civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., at the United Nations.

The crowd fills Kazar stadium in San Francisco.

What does the parallel escalation of America's involvement in the war and the rejection of it by many young adults and their elders mean for the immediate future of the United States? It's hard to say, but things look dark. Just as the struggle for civil rights sometimes looks like a second Civil War, complete with bloodshed, the battle between Hawks and Doves threatens to tear the country apart along political lines. Let's hope the nation is never as divided as it seems to be now.

Music to Argue With Your Parents or Children By

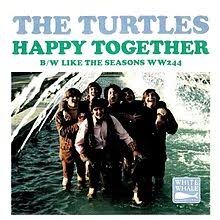

The tension between generations shows up in popular culture as well. A fine example of this happened recently. From late March until the middle of April, a cheerful little tune from the young folks who call themselves The Turtles was at the top of the American music charts. Happy Together is a great favorite of teenagers, I believe.

I like the part near the end, when the frequently repeated title changes to How is the weather.

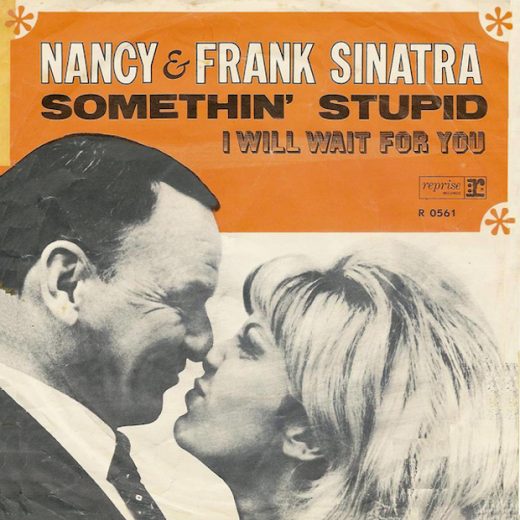

Mom and Dad are likely to prefer the song that replaced it as Number One this week. Veteran crooner Frank Sinatra, assisted by daughter Nancy, currently has the nation's biggest hit with the much more traditional number Somethin' Stupid.

I'll refrain from commenting on the propriety of having father and daughter sing a love song together.

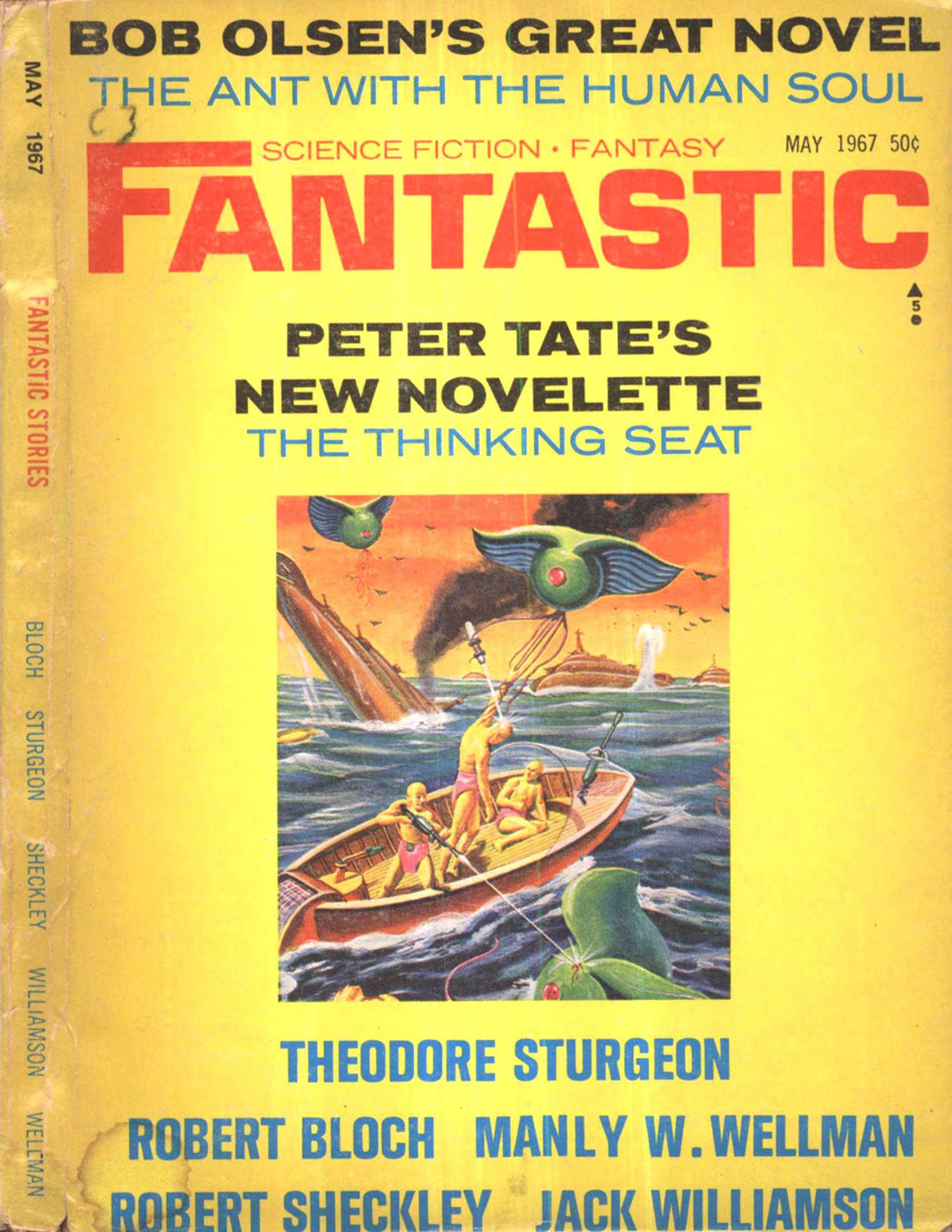

Not even speculative fiction escapes the conflict between generations. The so-called New Wave movement within the field, primarily in the United Kingdom, offers experimental, controversial, and sometimes incomprehensible stories to readers. The latest issue of Fantastic, a magazine which has been rather stodgy since it went to a policy of containing mostly reprints, mixes a bit of New Wave with plenty of Old Wave stuff.

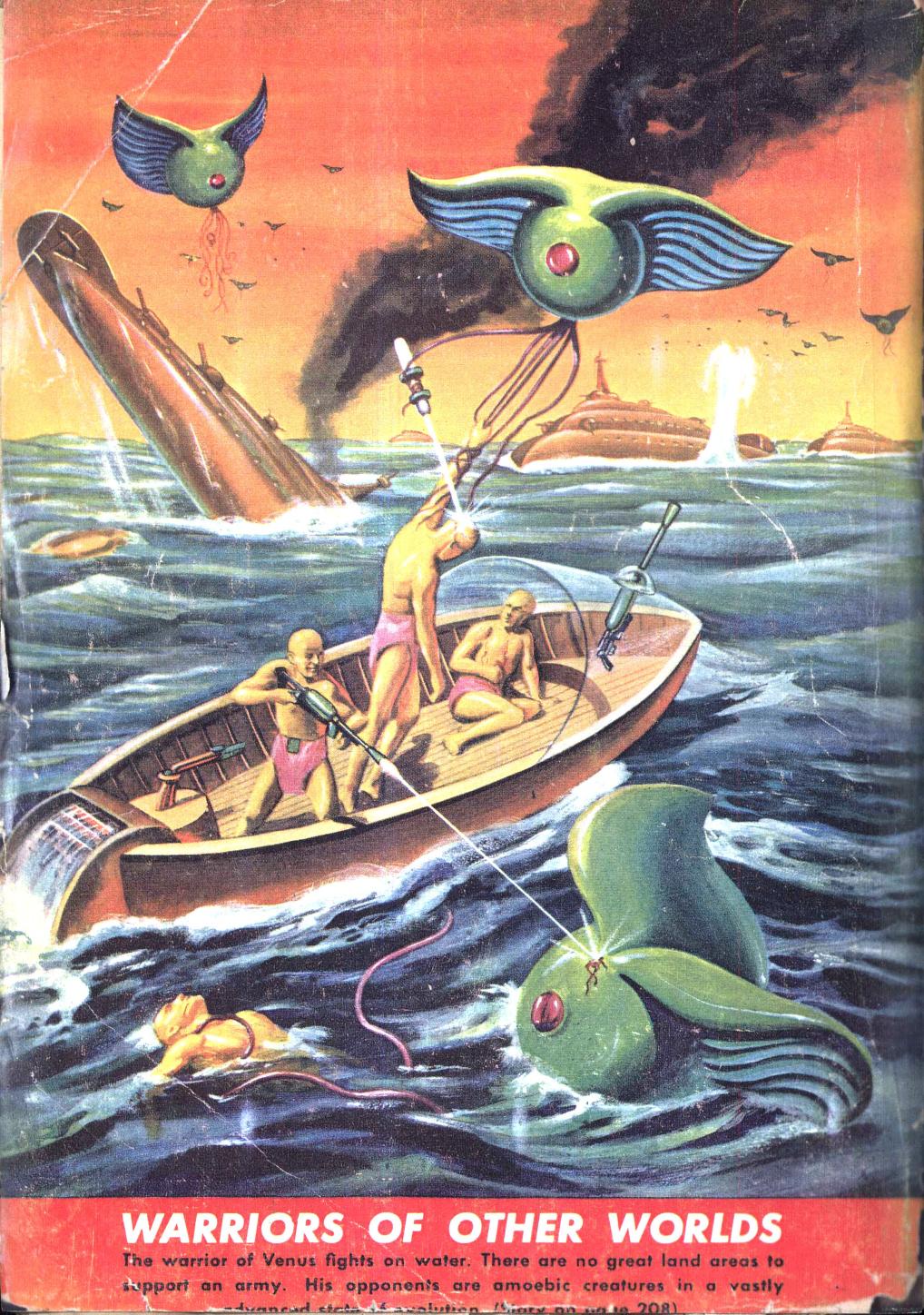

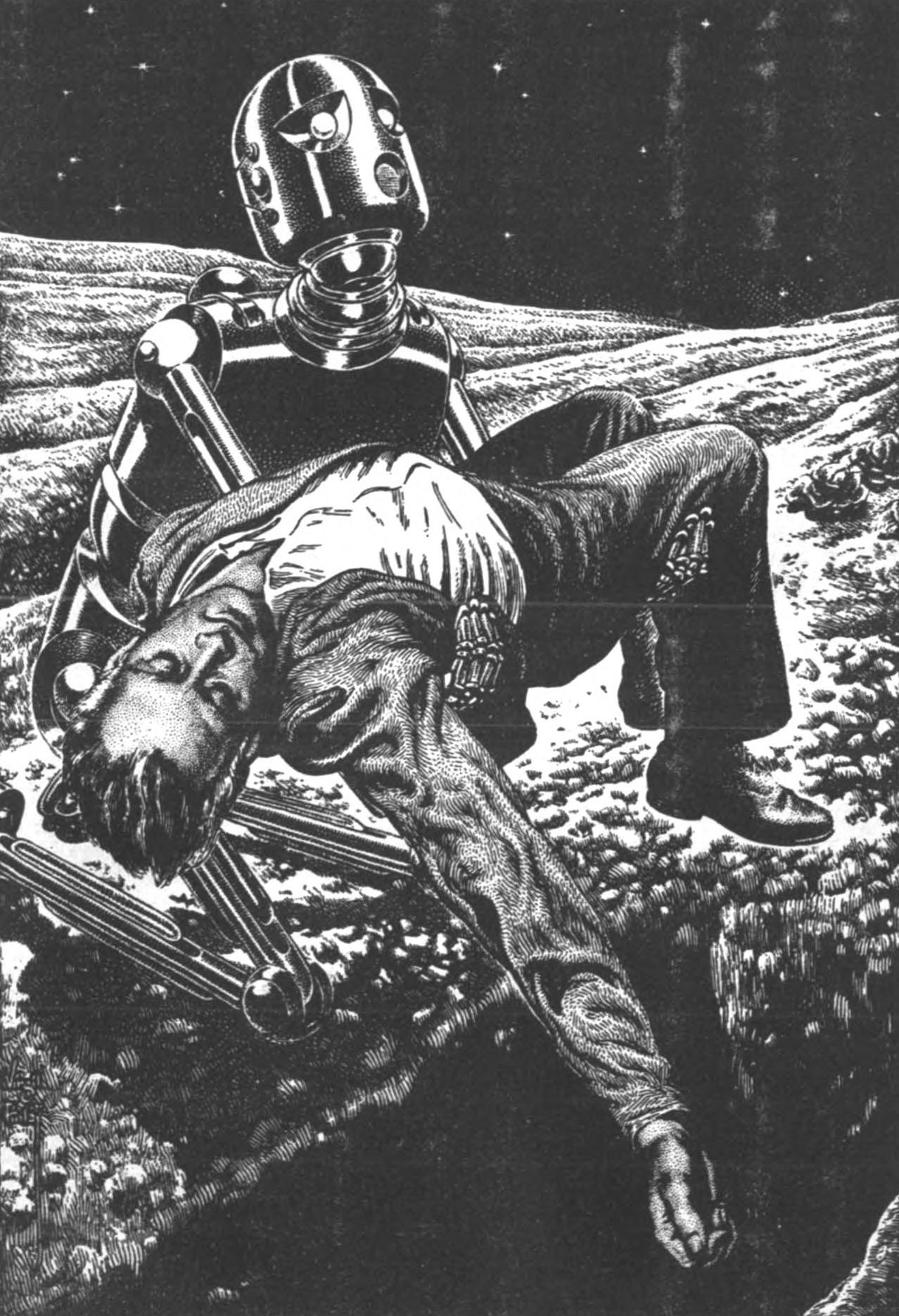

Cover art by Malcolm Smith.

As usual, the cover reprints art from an old magazine. In this case, it's from the back cover of the July 1943 issue of Fantastic Adventures.

The original looks a lot better.

The Ant with the Human Soul (Part One of Two), by Bob Olsen

Cover art by Leo Morey.

The whole of this Old Wave, pre-Campbell novella appeared in full in the Spring-Summer 1932 issue of Amazing Stories Quarterly. I guess Fantastic didn't want to devote most of the magazine to it.

Illustrations by Morey also.

The narrator tries to kill himself by jumping into the ocean, but a scientist rescues him. The scientist suggests a bizarre scheme. He has a gizmo that can increase or decrease the size of anything, even living creatures. He combines that with neurosurgery in order to perform a weird experiment.

First, he'll increase an ant to the size of a human being. After that, he'll put a part of the narrator's brain into the ant's head. When he shrinks the ant back down to normal size, the narrator will experience everything the ant does, and will be able to control the ant's actions. In essence, he will become the ant.

After the strange transformation takes place, the narrator takes us on a guided tour of life in an ant colony. This first part ends with a cliffhanger, promising the reader that a violent event is about to occur.

Mad Science!

This is an odd story, not only because of the outrageous premise. The mood varies wildly. Some sections deal with the narrator's loss of religious faith, which drove him to attempt suicide. Others are very lighthearted, with playful banter between the two characters. The best part of it is the description of life as an ant, which is depicted in vivid, accurate detail.

Three stars, mostly for taking me into the ant colony.

The Thinking Seat, by Peter Tate

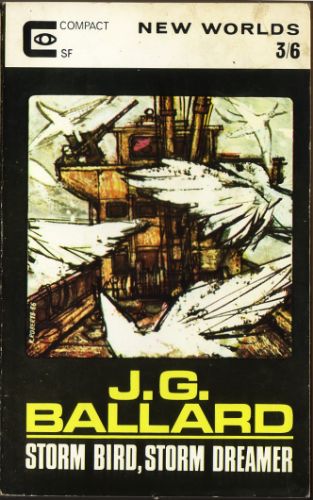

Cover art by Keith Roberts, better known to me as a writer.

The magazine calls this a new novelette, which is a half-truth. It's new to American readers, but it appeared in the November 1966 issue of the British publication New Worlds. My esteemed colleague Mark Yon reviewed it at that time, but let's take another look.

Illustration by Gray Morrow, which is the only truly new thing in the magazine.

The setting is the seacoast of California in the near future. The rugged shore has been replaced with artificial beaches of a tamer nature. The water is warmer, due to the discharge from a nuclear power plant. (I also got the impression that it made the water thicker, almost gelatinous, but I may be wrong about that. This New Wave story isn't always clear.)

A man and a woman with a strange relationship show up at a beatnik colony. She'd like to be more intimate with the fellow, but he doesn't seem interested. Instead, he becomes fascinated by a charismatic poet, who openly announces that he's going to take the woman away from the other man. Things come to a climax during an attempt to sabotage the nuclear power plant, as a way of protesting what it's done to the coast.

I have probably greatly simplified and distorted the plot, because this isn't the easiest story to understand. The narrative often stops to offer examples of obscure poetry, which adds more ambiguity. (Apparently the poet steals phrases from the Beat poets, but I don't know enough about their work to confirm that.)

I got the impression that this example of the Eternal Triangle, which ends badly, was really a case of repressed homosexuality. That's a theme you won't find in most Old Wave science fiction, to be sure. The whole thing works better as a study of the psychology of the three main characters rather than as science fiction.

Three stars, mostly for keeping me wondering about things.

A Way of Thinking, by Theodore Sturgeon

Cover art by Art Sussman.

The October-November 1953 issue of Amazing Stories supplies this supernatural chiller from the pen of one of the field's greatest stylists.

Illustration by Ernest Schroeder.

The narrator is a writer of science fiction and fantasy, who even mentions his work appearing in Amazing, so I assume it's a fictional version of the author. He tells us about an acquaintance who reacts to problems in unusual ways, often by thinking about things backwards. The fellow's brother is dying a slow, horrible death. The suggestion arises that it might have something to do a doll owned by the dying man's vengeful ex-girlfriend. The brother deals with the situation in his usual unorthodox manner.

This synopsis makes the story sound like a typical tale of voodoo, but that's misleading. I don't want to give too much away, but the plot goes in unexpected directions, and the climax is truly disturbing. Of course, given the author, it's very well written. It's not his most ambitious work, to be sure, but it succeeds as a horror story.

Three stars, mostly for the shocking conclusion.

The Pin, by Robert Bloch

Cover art by Mel Hunter.

From the December-January 1953-1954 issue of Amazing Stories comes another tale of terror.

Illustration by Lee Teaford.

An artist looking for a cheap studio comes across an abandoned loft. It's supposed to be empty, but there's a guy inside, surrounded by a huge pile of telephone books, directories, and so forth. The fellow stabs at random names in the books with a pin.

You may have already figured out that the pin causes the death of those whose names are selected. (The premise reminds me of Ray Bradbury's 1943 story The Scythe, as well as the 1958 movie I Bury the Living.) There aren't a lot of surprises in the plot, but it's an effective little thriller.

Three stars, mostly for creating an eerie mood.

Cold Green Eye, by Jack Williamson

Cover art by Richard Powers.

The March-April 1953 issue of the magazine offers yet another spooky tale. In its original appearance, it was called The Cold Green Eye. Don't ask me why they left out the first word.

Illustration by Ernie Barth.

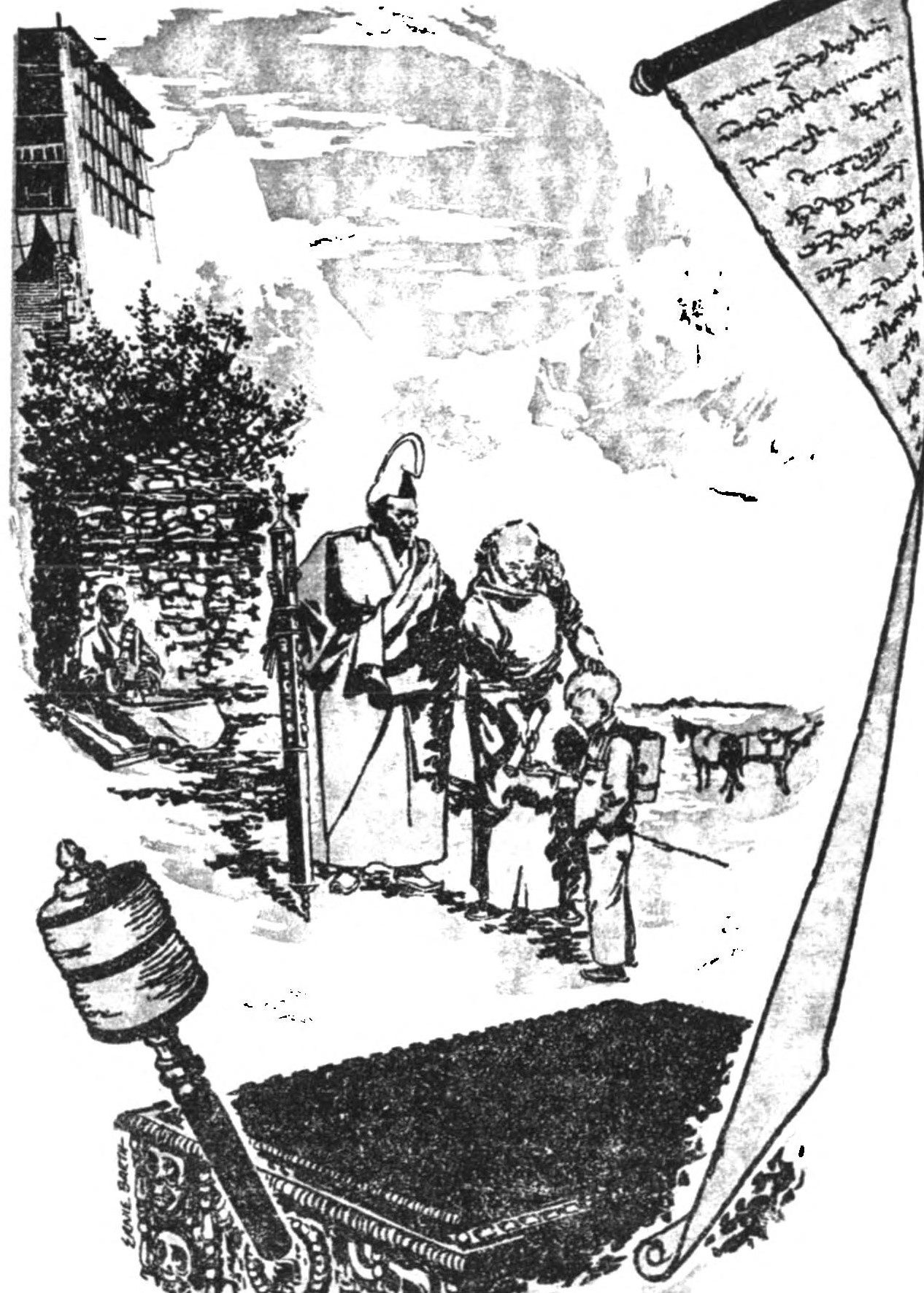

The child of a pair of daring explorers is raised by Buddhist monks after his parents die in a mountaineering accident. He's adopted by an aunt back in the United States. She's a harsh disciplinarian, punishing the boy for what she thinks of as his heathenish ways. In particular, she hates flies and kills them whenever she can, while the child believes in reincarnation and that all living creatures should be protected. Things get strange when the kid uses the sacred scroll he has in his possession.

There's a good chance you'll see the ending coming, although it still raises goose bumps. What's more surprising is that the cruel aunt is a devout Christian, in contrast to the boy's gentle Buddhism. I didn't expect that from an American horror story from more than a decade ago. Maybe the author just thought it made for a good story, and wasn't really trying to say anything about the two faiths.

Three stars, mostly for aunt's comeuppance.

Hok Draws the Bow, by Manly Wade Wellman

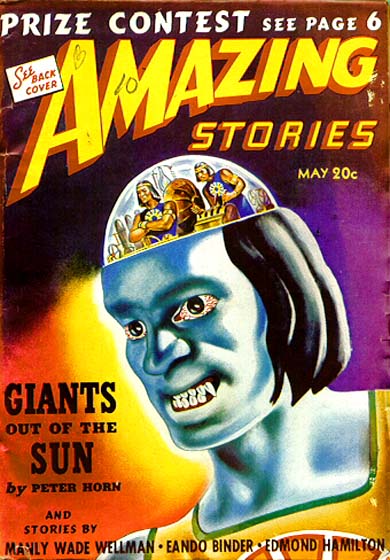

Cover art by C. L. Hartman.

Here's a sequel to a story that was reprinted in the previous issue of Fantastic. It comes from the May 1940 issue of Amazing Stories.

Illustrations by Robert Fuqua.

Once again our hero is Hok, a Homo sapiens fighting a war of extermination against sinister, cannibalistic Neanderthals. (It's best to forget about this story's version of prehistory and just think of it as a sword-and-sorcery yarn.) A fellow shows up bragging about his ability to project a spear farther than anybody else. That's because he's got a leather strap that he winds around it, sending it spinning.

The boastful man also has plan to take over Hok's clan, and he's particularly interested in Hok's pretty mate. He's made himself a god-like ruler over the Neanderthals, even teaching them basic military tactics. It looks like Hok's people will be wiped out, but our hero combines the man's strap and a throwing stick used by the Neanderthals to create a secret weapon.

That doesn't keep him from being captured. Fortunately, his mate has a throwing arm Sandy Koufax might envy.

The title and the opening illustration give away the fact that this story is about Hok inventing the bow and arrow. Other than that, it's an efficient adventure story.

Three stars, mostly for keeping things moving quickly.

Beside Still Waters, by Robert Sheckley

Illustration by Virgil Finlay.

The same issue as the Sturgeon story is the source of this tale. A spaceman lives on an asteroid, turning rock into soil that can grow crops and extracting oxygen from minerals. His only companion is a robot. The machine starts off only able to speak a few phrases, but over time the man teaches it to converse more fully. The story ends with a scene that tries to touch the reader's emotions.

The fact that the man can live on the surface of an asteroid unprotected, even if he somehow produces oxygen and food, is ludicrous. (Not to mention the fact that the asteroid's tiny gravity is going to send the oxygen out into space quickly.) The ending takes the plot into pure fantasy. An author best known for his wit tries to be sentimental here, and the result is bathetic.

Two stars, mostly for the excellent illustration.

Bridging the Gap

That was mostly a middle-of-the-road issue, coming to a sudden halt at the end. Maybe there's something to be said for mediocrity. If nothing else, both young and old can agree that the Old Wave and the New Wave have their ups and downs.

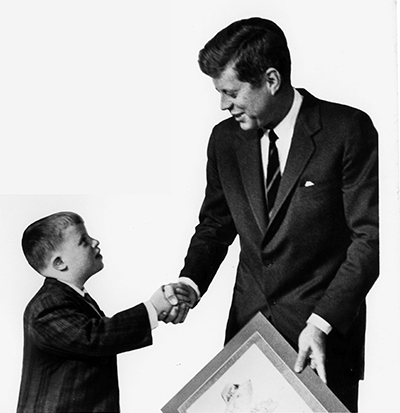

The late President Kennedy closes the generation gap.

Both of the songs you talk about have something creepy about them. "Something Stupid" as sung by the Sinatras père et fille as you mention, but "Happy Together" as well. The more I heard that one, the more I realized the object of the singer's affection doesn't even know he's alive. Is he just shy or a creepy weirdo? Every time I hear it, the more I lean to the latter.

Everything about "Ant" was terribly pulpy except for one thing: the writing. There's no purple prose, it has a distinct lack of exclamation points and stilted dialogue and exposition. Given more up-to-date subject matter, one might think it was brand new.

"The Thinking Seat" didn't do much for me. I see what both you and Mark saw in it, but on the whole it left me cold.

The Sturgeon was pretty good. It certainly left me wishing he'd write more often. Ted did spend some time in the merchant marine, so the narrator is most likely him. A lot of the old Weird Tales writers liked to do the author as character schtick.

The Bloch was a good example of Bloch at his best in the early 50s. Sure, you can see exactly where it's going, but it's an enjoyable trip.

The Williamson was also enjoyable, if predictable. Something like a gentle "Sredni Vashtar". I believe, though, that the boy was raised by Jains, not Buddhists. Buddhism never really caught on in Siddhartha Gautama's home.

"Hok" was a fine adventure story, but its prehistory left me sputtering. Completely skipping spear-throwers confused me, as did the ridiculous ease with which Hok invented the bow.

The Sheckley was certainly not one of his better works, though I may have liked it a little bit more than you did. Still not 3 stars, though.

re "attributed to Socrates" — incorrectly so, of course; it's a summary by a modern (well, 1907) author of his perception of the attitudes of the times:

https://quoteinvestigator.com/2010/05/01/misbehave/

Thank you for the comment, Victoria! At least you got an illustration in yours… *grin*

And for what it's worth, DemetriosX, these stories often leave me feeling rather unimpressed. All this allegory tends to mean that I'm left cold, too.