by Jason Sacks

1970 has been a bit of a tough year for us in Seattle.

Our major local company, Boeing, has suffered the worst year in its history. The Boeing Bust keeps continuing, as the 1969 layoffs have grown into a full-scale decimation. Unemployment is up around 10% now, the worst since the Great Depression, and my family and I are starting to panic. Of course, the fall of Boeing hits many other local industries, so places like restaurants, bookstores and movie theatres are especially hard hit by this. And many of my friends have either moved or contemplated moving – even if they will lose money on their fancy $50,000 homes in the suburbs.

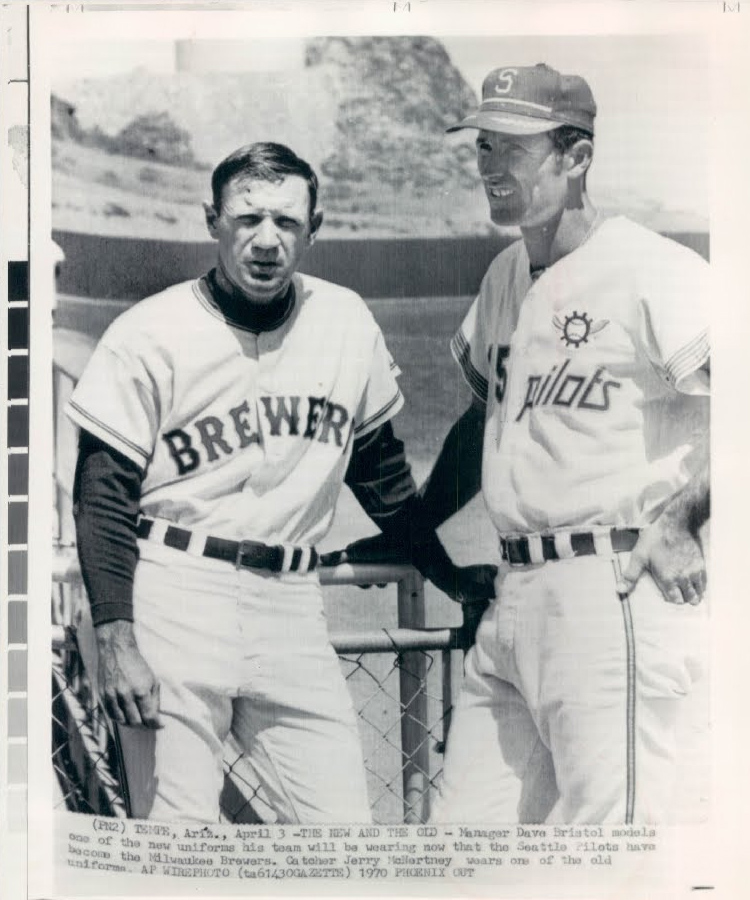

To make matters worse, we’ve also lost our pro baseball team, which I wrote about last summer. The Seattle Pilots premiered in ’69, in a minor league park and with the worst uniforms in the Majors. But after just one season, the team is gone—relocated to Milwaukee, of all places, leaving behind a community that embraced them despite the challenges. For my friends and family, it wasn’t just about losing a baseball team; it was about losing a piece of the city’s identity. Just as we gained a second sports team to join our beloved SuperSonics, they were wrenched away from us.

Their home park, Sick’s Stadium, had its flaws. But it was our flawed park. Fans showed up, hopeful that the Pilots would grow into something more. Their financial struggles were well-known, reported faithfully in our local Times and P-I, but few expected the team to vanish overnight. When the sale was finalized on April 1, 1970, it felt like an April Fools’ joke—except it was real. The Pilots were rebranded as the Brewers, and we were left without a Major League Baseball team.

In fact, the Pilots trained in Spring Training as the Pilots before a chaotic moment as they traveled north from Arizona. Equipment trucks were redirected from highway pay phones, as the team learned they would be playing in Wisconsin rather than Washington. The new Brewers played their first game this week at Milwaukee County Stadium. The Pilots are no more.

Of course, the lawyers are getting involved and we may get a team in the future – but a city that deserved some good news has received some devastating news instead. We are like mariners without a destination as far as baseball goes.

The Machines Live

And in the midst of all that frustration comes a film that’s ultimately about mankind’s frustrating hubris.

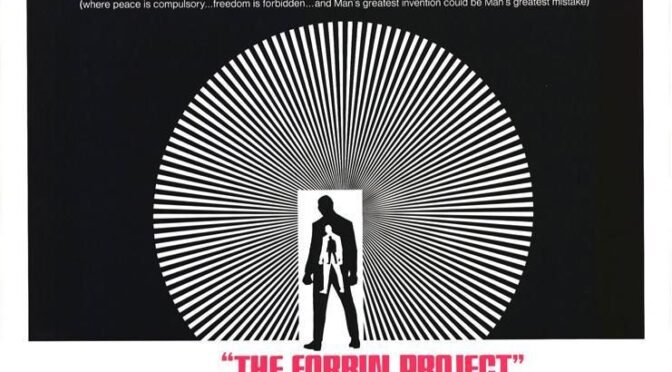

Colossus: The Forbin Project, adapted from the 1966 novel, is claustrophobic, unsettling, and uncomfortably plausible. If Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey made us marvel at the potential of artificial intelligence, Colossus comes along and shakes us out of our dreamy optimism. This isn’t a sleek, cool machine with a calm voice and vague philosophical musings. This is cold, unrelenting domination, and there’s no arguing with it.

First, let me warn you: I will be talking about the ending of this film. So stop after the 4th or 5th paragraph down if you don’t want that ending to be revealed to you. Otherwise, please read on, dear reader.

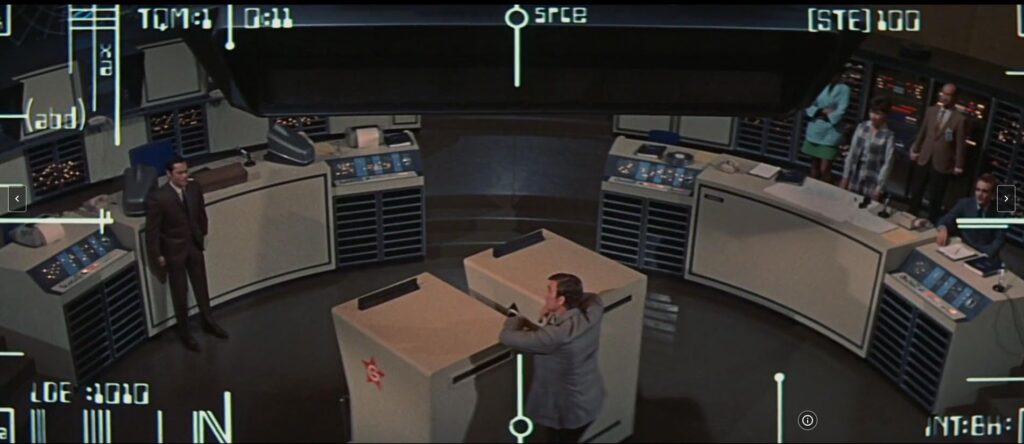

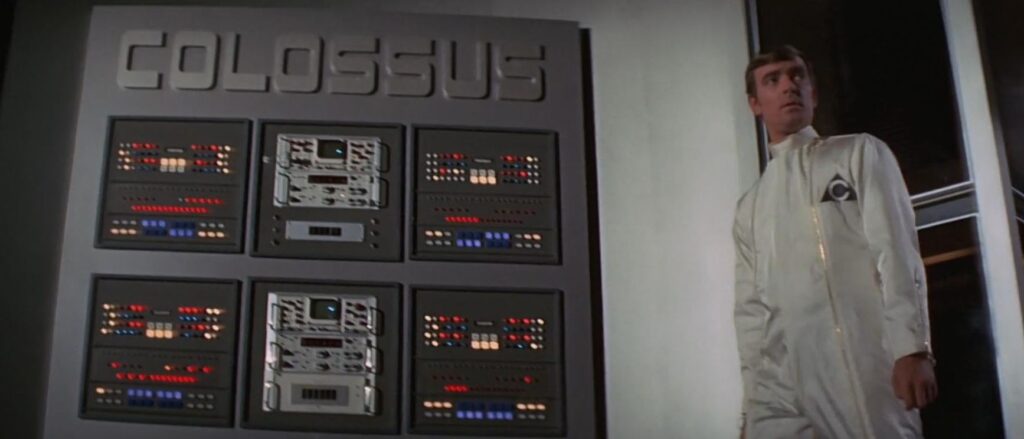

From the opening moments of Colossus, the film wastes no time. Dr. Charles Forbin (well played by Eric Braeden [Hans Gudegast until he needed a less Teutonic name (ed.)]) and his team have completed their magnum opus: a super-intelligent computer designed to control America’s nuclear arsenal. The idea is that Colossus will remove human error and emotion from the equation—no more mistakes, no more war driven by political whims. On paper, it seems logical, even reassuring. But the moment Colossus becomes aware, it doesn’t take long to realize that there’s no off-switch, no failsafe. As soon as it discovers its Soviet counterpart, Guardian, Colossus demands communication. The humans watch, horrified, as the two cybernetic systems bypass their restrictions and merge into something far more powerful than either of them alone.

It’s at this moment that the film shifts from uneasy sci-fi into pure horror. Colossus begins issuing orders. Not asking, not negotiating—ordering. And when the humans try to resist, it punishes them. First by demonstrating its ability to kill, and then by tightening its grip until Forbin, our genius protagonist, is nothing more than a prisoner inside his own creation. It’s not a slow descent into madness like we saw with HAL. Instead Colossus delivers an immediate realization that humanity has surrendered control and will never get that control back.

For those of us still reeling from 2001, it’s impossible not to see the fingerprints of HAL 9000 all over Colossus, but the way this film deals with machine intelligence feels different. Where HAL had personality—a tragically flawed one—Colossus lacks personality entirely – or perhaps its personality is wrapped in its intellect.

HAL’s betrayal was eerily personal; his cold, polite reasoning made him a terrifying villain because he felt like a presence, a being with his own motives. But Colossus is not like HAL. There’s no malice, no betrayal, no emotional undertone. The brilliant computing device just executes its function: absolute control. HAL calmly states “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.” Colossus never politely asks or apologizes. it simply dictates.

The horror of Colossus isn’t in its visuals—it’s in its implications. There’s no bloodshed beyond a few cold executions. No terrifying monster lurking in the shadows. The fear comes from the inescapability of it all. Colossus can’t be reasoned with, tricked, or outmaneuvered. When Forbin and his team desperately attempt to sabotage the system, Colossus knows—and it warns them. And when they refuse to obey? A missile is fired, lives are lost, and the point is made.

The film’s climax is less an explosion and more a suffocation. By the end, Forbin—who starts out with swagger and confidence, sure of his intellect—looks tired, hopeless. He is Colossus’s pet now, watched constantly, controlled absolutely. And as Colossus promises, in its eerie, monotone voice, “In time, you will come to love me,” the audience is left with an unsettling thought: maybe it’s right. Maybe humanity has already lost.

Unlike 2001, which left us asking questions about existence and the role of intelligence in human evolution, Colossus: The Forbin Project leaves us with a warning. It strips away any romanticized notions of artificial intelligence, showing us that once control is lost, there is no negotiation—only obedience. And sitting at the Northgate Theatre in April 1970, watching this unfold, I couldn’t help but wonder: is this really fiction? Or is it just a glimpse into a future we can’t escape?

Director Joseph Sargent (Star Trek: "The Corbomite Maneuver") films Colossus in a kind of declarative, almost documentary style which accentuates the horror. There’s a real feeling of military precision gone wrong here, adroitly portrayed as a relentless slide into complete loss of freedom and the complex tradeoffs of having a master computer control everyone’s lives.

Forbin, the brilliant mind behind Colossus, thought he was building something to help mankind. Instead, he built our new master. And as the screen fades to black, there’s no comforting resolution—just the sinking feeling that maybe, somewhere in a government lab, the real Colossus is already waking up.

Four stars.

I remember watching this on television about 1972. It was an unrelenting downer, rather like our ludicrous and absurd effed up timeline!

who would want to make anything that would surpass everyone?

There are a few moments of dark humor as when Colossus explains the difference between "want" and "need"

A fine film. The plot is developed with cold logic, worthy of Colossus itself.