by Gideon Marcus

Common meaning

Every so often, a science fiction magazine editor has enough of a backlog to run a "themed" issue. For instance, there was the time Fred Pohl bunged together an issue of IF with stories all by someone named Smith. This time around, Analog editor John Campbell has accumulated a supply of tales on the subject of communication.

The problem with themed issues, of course, is that quality is often secondary to topic. But not always. Let's see how the July 1966 Analog fares before we make a hasty conclusion!

Five by Five (plus two)

by John Schoenherr

The Message, by Piers Anthony and Frances Hall

by John Schoenherr

Mysterious Thargans have settled amidst the tiny human colony on Tau Ceti. Though not overly aggressive, they aren't terribly congenial either. But they are very inquisitive, about our technology, our physical capabilities, and our mental talents. And their spaceship has a lot of cargo space — enough to fit a thousand slaves, for instance…

Rivera, a linguist who speaks the alien tongue, is tapped to assess the danger posed by the Thargans. And when disaster inevitably strikes, he must recapitulate an era early in his life, when he managed to foil four would-be muggers not by force, but by the right verbal approach.

An interesting tale by a pair of newish writers, though a bit choppy and with flattish characters.

Three stars.

The Signals, by Francis Cartier

by Kelly Freas

For the last half-decade, astronomers have been training their radio telescopes upon the stars, hoping to eavesdrop on transmissions from an intelligent alien race. So-called Project Ozma hasn't found anything yet, and Cartier's tale explains why. It's not that aliens aren't trying, it's just that we don't know how to listen. Or more accurately, the fundamental theory of communication is too different between the species for intelligible contact.

Something of a throwaway piece, it is nevertheless cute and probably not far from the truth. Three stars.

An Ounce of Dissension, by Martin Loran

by Kelly Freas

Quist of the interstellar Library corps is visiting the planet Rayer after a long trip through space. Upon landing, the brutalist police troops burn his entire stock of books. The planet is ripe for a revolution, but it needs a catalyst to do so. Luckily, in Quist's cargo is a crate-sized book printer with a very large memory core…

Essentially a smug Fahrenheit 451, I can see why this piece appealed to Campbell. But it takes too long to get where it's going, and it utilizes enough straw men to staff all the fields of Iowa.

Two stars.

Meaning Theory, by Dwight Wayne Batteau

This nonfiction piece is all about how the communication of information destroys meaning, and the imparting of meaning destroys information…or something like that. Frankly, I couldn't make heads or tales of it. The pictures are cute, the graphs seem useful, the text is in English. Perhaps someone smarter than me will glean something from it.

Or maybe not. One star for this failure to communicate.

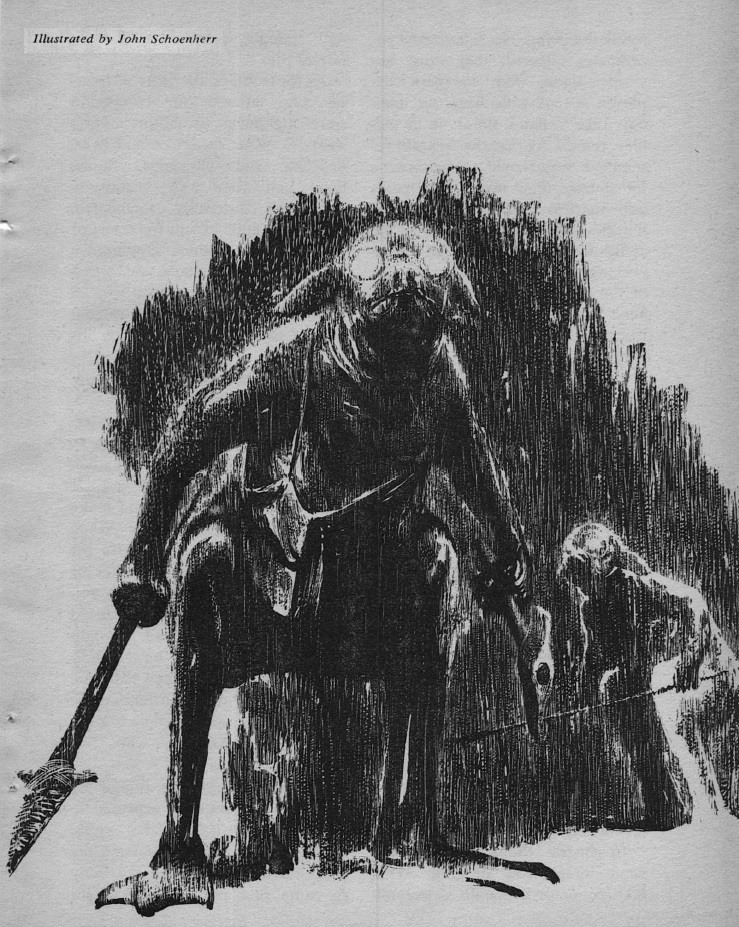

The Ancient Gods (Part 2 of 2), by Poul Anderson

by John Schoenherr

Last issue, the crew of the starship Meteor had space-jumped 200 million light years from Earth to a feeble red dwarf out in intergalactic space. They had hoped to establish trade relations with the advanced "yonderfolk" of the system. Instead, they transitioned into real space too close to the next planet closer to the sun and crash landed. Only six were left alive.

Hugh Valland, oldest of the more-or-less immortal group of spacers, hatched a plan to salvage a lifeboat so as to make the interplanetary trek to the yonderfolk planet. But such a massive undertaking would require more than the half dozen remaining crew. Luckily, intelligent (if primitive) beings exist on the swampy world. Contact was made with the Azkashi, and it looked as if the plan might work. As the first half came to a close, it seemed we might be getting a Flight of the Phoenix story.

Instead, the second half begins with Hugh taken prisoner by the Askashi while the related but more advanced Gianyi abscond with the captain and the mentally unstable Yo Rorn. It is quickly determined that the Gianyi are in the telepathic thrall of the Ai Chun, a race perhaps a billion years old. They have stagnated to almost fossilization, and no amount of parley can dissaude them from their goal to strip the downed spaceship for its valuable metal and to work the humans as slaves until they die. The captain escapes, and with Valland (who is freed by the Azkashi), plans a battle for their liberty.

Much of this installment is given to the war between the human-led Azkashi and the Ai Chun-controlled Gianyi. It is effectively told, but the outcome is never in doubt, and I found myself less enamored with this wide swath of the text. Long story short, there are happy endings and Hugh is ultimately reunited with his long lost love (of whom much is sung but little is known).

What I liked: Poul Anderson is a bard, and his stories are lyric performances. His wistful, archaic prose is sometimes ill suited to its subject, but it works here. The characters are nicely drawn and compelling. The unique setting and the nifty aliens are all cutting edge science. I appreciated the frank polygamy practiced by the captain and his genuine puzzlement with Valland's monogamy. There's also the suggestion that strict heterosexuality is not observed in the far future.

What I was less delighted with: I felt like Anderson marked a lot of time with the war sequences, which did not bring much new to the table. The acute lack of women, both on the crew of the Meteor and among the aliens (they exist in the background to do domestic chores, just like Earth females) marked another missed opportunity. I also suspect that the Ai Chun and Gianyi are supposed to be metaphors for China — grand but hidebound. Certainly Anderson draws a stated parallel between the Azkashi and the American Indians (for whom the author has an obvious fondness; viz. his tale in Orbit). The racial comparisons made me slightly uncomfortable, though it's a minor thing and I could be wrong.

Finally, the revelation of Mary O' Meary's current condition in the story's epilogue is a bit trite, and quite unbelievable. Here's the thing (and don't read on until you've either read the end or in the event you don't mind me giving away the gimmick): Mary has been dead for thousands of years, having passed away just before the advent of immortality. She died at the age of nineteen. This means that the immortal romance between she and Hugh could have lasted a few years at the most.

Now look, I love my wife more than anything. If she passes before me, I may well stay single for the rest of my life. But she and I have been together almost 30 years. I balk at the idea that a teenage fling could possibly compel me to asceticism for thousands of years. At that point, it's less about love and more a case of emotional masturbation.

Anyway, it's a solid three and a half stars. I can imagine some ticking it up to a full four stars and others finding it all a bit tedious and giving it just three.

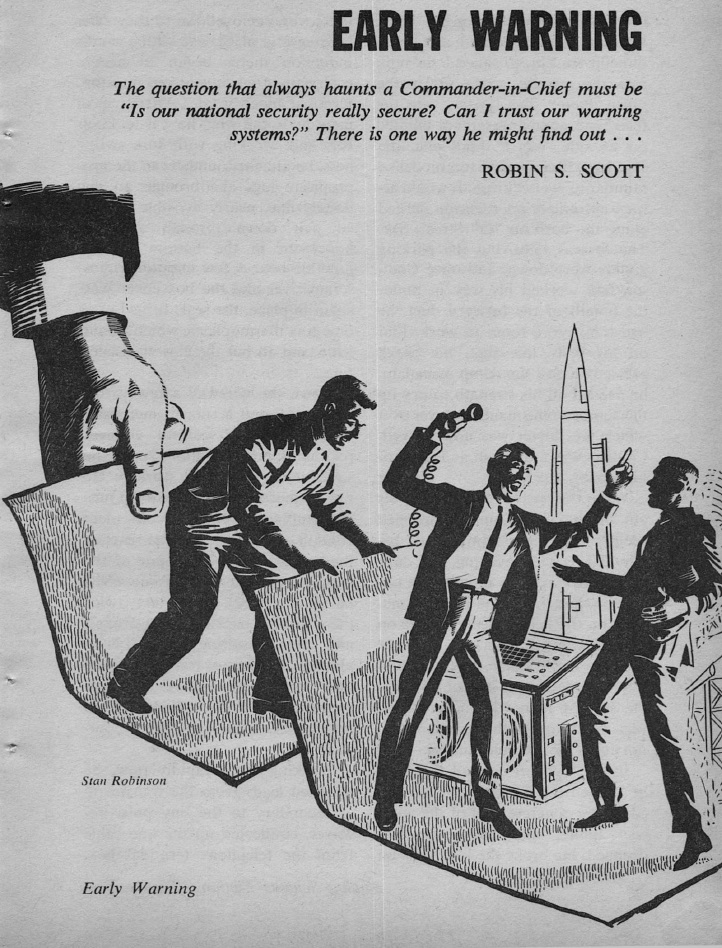

Survivor, by Mack Reynolds

by Kelly Freas

The threat of nuclear war looms, raising tensions to the breaking point. When the klaxons go off, signalling the end of the world, millions flee the cities to find refuge, fighting over the quickly dwindling resources.

But have the bombs actually fallen, or is it all a miscommunication?

The premise to Survivor is pretty darned silly — that everyone will lose their collective minds out of fear. I do believe that, in the case of a false alarm, there'd be panic and rioting and looting and mass disruption. But not to the point that society completely breaks down such that both sides aren't even able to wage the war that frightened everyone in the first place!

Two stars.

The Missile Smasher, by Christopher Anvil

by Kelly Freas

Lastly, Anvil offers up a predictably slight tale of a series of rocket launch mishaps, the discovery of the focused light projector that is causing it, and the removal of said projector by a government troubleshooter.

I think it's meant to be funny or something. It's not very good.

Two stars.

Wrong number

I'm afraid a common theme did little to elevate the current issue. Indeed, in many cases, background noise might have been preferable to signal. All told, the July Analog clocks in at a dismal 2.3 stars, placing it at the bottom of the heap. The top is dominated by paperback-format periodicals: New Writings #8 (3.9), Fantastic (3.4), and Orbit #1 (3.4)

The middle of the pack is composed of the usual suspects: Fantasy and Science Fiction (3.1), Impulse (3.1), New Worlds (2.8) and If (2.7).

Women were responsible for a whopping 14% of this month's output of new fiction (mostly thanks to Orbit, which featured five female authors). If you took all the really good stuff published this month, you could comfortably fill two magazines. Or just buy New Writings and Orbit!

So, whither Analog? Will there be another theme next month, one that will drag the magazine ever closer to the dreaded 2-star rating? Will it plunge even without a common thread? Or will we get a sudden reversal, the kind we've seen several times over the past few years?

Stay tuned!

Speaking of tuning, tune in to KGJ, our radio station! Our theme is quality and diversity!

![[June 30, 1966] Not Reading You (July 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660630analog-500x372.jpg)

![[May 31, 1966] Worth Remembering (June 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660531cover-672x372.jpg)