by John Boston

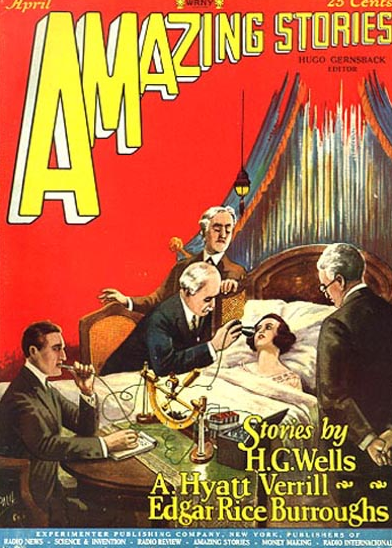

The legendary Hugo Gernsback died August 19 at the age of 83. He started the first science fiction magazine—the first seven of them, in fact. He is memorialized every year in the Hugo Awards for the best SF of the year. Sam Moskowitz once proclaimed, “Everyone today knows that the real ‘Father of Science Fiction’ is Hugo Gernsback and no one can ever take the title away from him.” (Moskowitz, A Profile of Hugo Gernsback, Amazing Stories, Sept. 1960, p. 38.)

by Frank R. Paul

But it’s an odd sort of paternity, since plenty of what we think of as science fiction—works by Verne, Wells, Poe, A. Conan Doyle, M.P. Shiel, and Mary Shelley, among others—preceded Gernsback’s involvement, and in some cases his birth. Opinions are also mixed concerning the merit of much of Gernsback’s SF-related activity. But before passing any judgments, let’s step back and look at Gernsback’s life and career, relying heavily on Moskowitz’s above-quoted article and its revised version in his book Explorers of the Infinite. (A more thorough exploration of Gernsback’s rather full life might make a substantial book for some future scholar.)

Gernsback was born in 1884 in Luxembourg, came to the United States in 1904, quickly got into the electrical business manufacturing automobile batteries, and later started an electrical import business. He devised a low-cost home radio set which was sold widely, followed by the first working walkie-talkie. In 1908 he started Modern Electrics, the first magazine of its kind. He started the Wireless Association of America in 1912, which soon had thousands of members. He founded a new magazine, Electrical Experimenter (later Science and Invention) in 1912, and another one, Radio News, in 1919. In 1925 he started a radio station, WRNY, which also made some of the earliest rudimentary television broadcasts. Someone with Gernsback’s cornball sense of humor might say that during those two decades, he was quite a live wire, and encountered little resistance.

Gernsback demonstrating his "Isolator," designed to aid concentration by preventing distraction from external stimuli (Science and Invention, July 1925)

Gernsback also dallied with science fiction early on. (Gernsback’s own more detailed account of these activities is in his Guest Editorial: Science Fiction That Endures in the April 1961 Amazing.) He wrote the novel with the punning title Ralph 124C41+ (say it out loud), subtitled A Romance of the Year 2660, and serialized it as he wrote it in his own Modern Electrics in 1911. I haven’t dared try to read it, but it is reputed to be short on literary elements but quite long on predicted future inventions and discoveries, including both radar and space-sickness. He published others’ fiction as well as his own in Modern Electrics and in Electrical Experimenter and its successor Science and Invention. His series Baron Munchausen’s New Scientific Adventures began in Electrical Experimenter in 1915.

In fact, before Gernsback published the first SF magazine, he published the first SF magazine issue: the August 1923 Science and Invention was blurbed “SCIENTIFIC FICTION NUMBER” and left us such treasures as G. Peyton Wertenbaker’s The Man from the Atom. And in 1924, he made his first abortive attempt to start an SF magazine, Scientifiction, but his large mailing soliciting subscriptions fell flat.

Which brings us to 1926 and the birth of Amazing, this time with no advance solicitation. The first issue, dated April 1926, included nothing but reprints and foregrounded Wells, Verne, and Poe, but original fiction began to appear quickly enough, with G. Peyton Wertenbaker’s The Man from the Atom (Sequel) in the May issue and his The Coming of the Ice in June. By late 1928, almost all of the magazine’s contents were original material.

by Frank R. Paul

Gernsback quickly expanded his empire with the very large Amazing Stories Annual in 1927, featuring a specially commissioned Mars novel by Edgar Rice Burroughs, and followed it with Amazing Stories Quarterly, which also ran a complete novel in each issue.

But a rude awakening was in store. Gernsback liked to make money, but he was less fond of paying it out, to his authors or anyone else. H.P. Lovecraft dubbed him “Hugo the Rat” for paying so little for The Colour out of Space, one of his best stories, and H.G. Wells refused further reprint permissions because of Gernsback’s low rates. Though Gernsback was very far from broke, in 1929 his company was forced into bankruptcy by creditors who had not been paid on time, as permitted by the law at the time. Its assets were sold, with Amazing going to Teck Publications. Ultimately the creditors were paid $1.08 on the dollar (“bankruptcy de luxe,” as Moskowitz quotes the New York Times).

Undaunted, Gernsback announced by mass mailing that he would publish Everyday Mechanics in place of (and to compete with!) Science and Invention, Radio-Craft in place of Radio News, and Science Wonder Stories in place of Amazing. This time, his solicitation worked. He received thousands of subscriptions and was quickly back in business. The last Amazing listing Gernsback as editor was April 1929; the first issue of Science Wonder Stories was dated June 1929. He promptly added Science Wonder Quarterly, Air Wonder Stories, and Scientific Detective Monthly to his stable, though only the quarterly lasted more than a few issues.

by Frank R. Paul

Gernsback’s new ventures were successful. For much of the early ‘30s, Wonder Stories (“Science” was dropped in 1930) was reckoned the best of the SF magazines. By 1936, however, Depression economics had defeated Gernsback, and he sold Wonder Stories to Standard Magazines, where it became Thrilling Wonder Stories, a relatively juvenile pulp magazine. For the first time in a decade, Gernsback was out of the SF business.

Unattributed

Gernsback's attempts to get back into the game were abortive. He started Superworld Comics, an SF comic book, in 1939, but it quickly failed. In 1953, he started Science Fiction Plus, in the same large size as the early Amazing, bringing back artist Frank R. Paul and some of the writers from his earlier magazines as well as more current fare, but this largely reactionary venture lasted only seven issues. Though he continued to publish other magazines, notably Sexology and Radio Electronics, his contact with the SF world diminished mostly to the occasional convention visit.

by Frank R. Paul

Most SF readers from the mid-‘50s on probably know of Gernsback, if at all, from his postage stamp-size photo and endorsement that appeared irregularly on the back cover of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, along with those of such other 1950s celebrities as Clifton Fadiman and Spring Byington. His message, as seen on the October 1960 F&SF: “Plus ça change, plus c’est le meme chose—is a French truism, lamentably accurate of much of our latter day science fiction. Not so in the cyclotronic Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction which injects sophisticated isotopes, pregnant with imagination, into many of its best narratives.” Sure.

F&SF, April 1959

So—the “father of science fiction”? Not by decades. But Gernsback certainly was the father of the commercial marketing category of science fiction, or, some would say, SF’s ghettoization. Before Gernsback, SF or proto-SF could be found regularly if not frequently in general fiction magazines of the US and the UK and in the lists of book publishers. But Gernsback’s Amazing Stories, begun in 1926, was the first periodical devoted entirely to “scientifiction”—the first of what eventually became a legion.

It’s easy to overstate Gernsback’s significance here. It is nearly certain that there would have been science fiction magazines quickly enough had Gernsback never existed. From the late 1920s on, pulp fiction magazines multiplied rapidly, specializing to satisfy every conceivable interest—westerns, romances, western romances, “spicy” (mildly suggestive) stories, crime fiction hard-boiled and soft, sports stories, horror and “weird menace” stories, aviation and air war stories. The quest for market niches led to even narrower specialization: Zeppelin Stories (1929, four issues); Prison Stories (1930-31, six issues); The Wizard: Adventures in Moneymaking (1940-41, seven issues, three under a new title); Civil War Stories (1940, one issue).

And new ventures required little encouragement. Astounding Stories of Super-Science, the first SF magazine started by anyone not named Gernsback, was apparently launched after William Clayton, publisher of 13 magazines, realized that he could add more titles cheaply because pulp covers (a major part of the publishing cost) were printed in sheets of 16, and he had blank spaces available. The self-interested machinations of Clayton editor Harry Bates then tipped the scale towards Astounding and away from the competing proposal, Torchlights of History. (Bates, “to begin” (sic), Editorial Number One in Alva Rogers, A Requiem for Astounding (1964)). In Gernsback’s absence, others besides Clayton would surely have found and filled the niche for scientific fiction magazines.

But it is also easy to understate Gernsback’s contributions. One of them was his facilitation of SF fandom—initially, simply by printing letter-writers’ addresses in Amazing’s letter column, so they could communicate with each other, and later by creating the Science Fiction League with its organizational framework and local chapters. SF editors have expressed mixed feelings about fandom’s activities and influence, but at the least it has been valuable to have a semi-organized claque to speak up about the worst tendencies in SF publishing, such as the “Shaver mystery” featured in the mid-‘40s Amazing and finally dropped under pressure.

Gernsback’s other major contribution was his pretenses. From the beginning, he proclaimed “scientifiction” to be a means of scientific education and speculation—as exemplified in his own Ralph 124C41+ and its exhausting parade of future inventions—and he continued to express that view in Wonder Stories, notwithstanding his dropping “Science” from the title. I say “pretenses” because much of the fiction he published was not especially scientific or educational, such as the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs and A. Merritt that appeared in his magazines as early as 1927. That is no surprise, since regardless of his preferences he had to attract enough readers to keep his magazines going.

But still, he would raise the flag now and then, such as in his editorial in the first Science Wonder Quarterly: “In publishing a number of science-fiction magazines, the editors feel that they have a great mission to perform; their mission being to get the great mass of readers, not only to think what the world in the future is likely to become, but also to become better versed in things scientific.” (Science Wonder Quarterly, Fall 1929, p.5) And sometimes he broadened his prescription. Commenting on the Technocracy movement of the ‘30s, which proposed to reorganize society along more scientific lines, he wrote: “. . . [T]he great mission of science fiction is becoming more recognized, day by day. This is the triumph of our readers over those who scorned science fiction. If science fiction can make serious people sit up and take notice, and THINK about the future of humanity, it will have accomplished a tremendous good.” (Wonder Stories, March 1933, p. 741)

The idea that SF should be held to higher standards and purposes than the run of pulp fiction may have made a considerable difference. One need look no further for a counter-example than the first new non-Gernsback competitor, Clayton’s Astounding Stories of Super-Science. Alva Rogers says in his informal history A Requiem for Astounding that the Clayton magazine “was unabashedly an action-adventure magazine and made no pretense of trying to present science in a sugar-coated form as did, to some extent, the other two magazines.”

by Hans Wessolowski

You can bet that little of the social speculation and satire, somewhat featured in Gernsback’s magazines and considerably more prominent in the SF of the ‘40s and ‘50s and later, showed up there either. Had Clayton’s magazine rather than Gernsback’s become the template for magazine SF, we would likely have had a much different and less interesting genre in the ensuing decades.

So—hail and farewell, Pops.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[August 20, 1967] Hugo Gernsback, 1884-1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/gernsback-1929-486x372.png)

![[March 16, 1967] A Matter of Life and Death (<i>Why Call Them Back From Heaven?</i> by Clifford D. Simak; <i>Tarnsman of Gor</i>, by John Norman)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670316covers-672x372.jpg)