KGJ News has a new episode for the week!

All you need to know in just four minutes:

by Fiona Moore

Having had the opportunity to attend a premiere of George Pal’s latest movie, “The Power”, as the guest of a friend who works at Borehamwood, I’d recommend it for any fans of the current crop of mind-bending, psychedelic, nightmare movies.

An image I'm not going to remove from my brain easily

An image I'm not going to remove from my brain easily

The story (which takes place, according to the chronon at the start, “tomorrow”) revolves around a facility whose purpose is to test the limits of human endurance, with the specific aim of identifying people with the qualities required to live in space. One of its directors, an anthropologist, has been conducting tests on his fellow board members as a pilot project for a survey of the wider population, and discovered that someone in his sample possesses more-than-human talents, including the ability to bend others to their will, to create illusions in the mind, and even, apparently, to use these powers to kill.

After the anthropologist meets a strange death in a gravity-simulating centrifuge, leaving behind a cryptic note appearing to blame someone named “Adam Hart”, our hero, Tanner (George Hamilton), investigates, while his mysterious antagonist seems to be constantly one step ahead of him, killing off board members one after the other and framing Tanner for the murders, though never quite managing to do in Tanner himself. The final confrontation of the film reveals the true reason for his miraculous survival.

Can *you* spot the bad guy?

Can *you* spot the bad guy?

The film’s weak points are largely in the scripting area. The plot is thin, though, to be fair, the action is so non-stop you don’t really notice. I was able to guess who the culprit was fairly early on, just through process of elimination and through considering the sorts of roles various actors are usually cast in, and there’s a party scene two-thirds of the way through which is simply interminable. Although the concept of an institute aimed at testing human endurance is interesting, the link to the space programme is fairly sketchy and seems mostly included as a way of justifying the centrifuge scenes. The idea of an ubermensch who is “the next stage of human evolution” is also well-worn: the film is based on a 1954 book of the same title by Frank M. Robinson, which may explain the use of a conceit which will, these days, strike the well-read sci-fi fan as more than a little bit dated.

The characterisation is also fairly light and boiler-plate. There’s the handsome young man, the pretty girl, the bow-tied scruffy scientist and his unhappy alcoholic wife, the seen-it-all cop, and so on. The casting is about what you’d expect, including as it does George Hamilton, Michael Rennie, Suzanne Plechette and, erm, “Miss Beverley Hills”. While all the performances are solid, none particularly transcends what you’d expect for a thriller movie.

On the other hand, handsome people do get their kit off a lot.

On the other hand, handsome people do get their kit off a lot.

The thing that saves “The Power” from being just another schlocky thriller is the imagery. George Pal treats us to genuinely nightmarish sequences of mental manipulation, such as a scene where a character is trapped in his own office, the doors and windows apparently disappearing every time he turns around. Another powerful sequence has Tanner unable to get off of a fun-fair merry-go-round, with the images flicking back to the centrifuge which was the site of the original murder. There’s one scene which will ensure you never trust one of those ubiquitous dipping-bird toys ever again.

George Hamilton about to have an encounter with a dipping bird.

George Hamilton about to have an encounter with a dipping bird.

Pal also cleverly plays with the mental-manipulation conceit. For instance, at one point Tanner is lured through a desert by the image of an oasis, which the viewer interprets as another obvious illusion—until we discover that it is all too real, and is a target area on a USAF gunnery range. At another, Tanner sees the familiar words of a “DON’T WALK” sign turn into the sinister command “DON’T RUN”, and, several scenes later, is startled to see the words “DON’T RUN” on a newspaper headline… only to realise that the headline refers to a political incumbent warning off a potential rival from taking him on in an electoral race, and the use of the phrase is simply a coincidence. The landscapes around our hero also take on nightmarish qualities, with even the ordinary setting of a suburban garden becoming like a lush, mysterious jungle, and the scenes taking place in the desert seeming genuinely alien. The film’s ability to take ordinary, even pleasant, settings like fun-fairs, toyshops, conferences and parties and turn them into sinister, terrifying sequences recalls The Prisoner in places.

There are other good things that stand out in the movie. German, Japanese and Eastern European characters appear without their ethnicity being a plot or character point (although the German does briefly sermonize about how living under the Nazis has given him insight into the dangers of charismatic supermen). There are several female characters with names, even if they do only talk to each other fairly briefly, and Suzanne Plechette’s love interest character is disappointingly flat and dull, her most memorable scene being a censor-baiting coitus-interruptus with Hamilton. It’s also worth re-watching the early scenes once you know who the villain really is. As noted, the film also maintains at best an ambivalent attitude towards the idea of supermen, and the question of whether or not they can be good people: Tanner at one point muses that absolute power corrupts absolutely.

Mrs Van Zant is Japanese, and why shouldn't she be?

Mrs Van Zant is Japanese, and why shouldn't she be?

“The Power” is, in sum, surprisingly good…for an SF horror blockbuster, with a few nice twists and an entertaining approach to the concept of the mind-manipulating superhuman being. It certainly sets a new high standard in visual effects and unreliable storytelling to challenge future filmmakers in this area. It's still plot-thin and character-lite, however.

Three out of five stars.

![[February 12, 1968] The Power of Cinema (<i>The Power</i>, a movie)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680212poster-672x372.jpg)

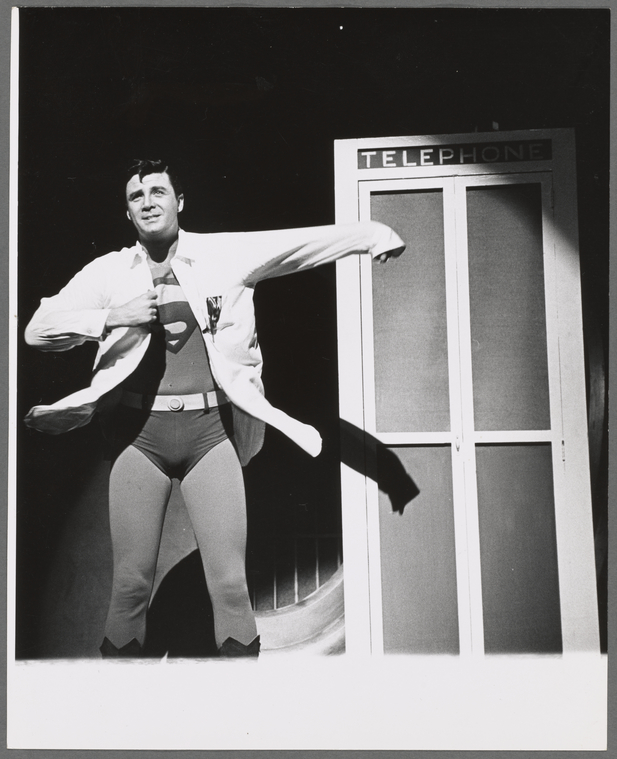

![[August 4, 1966] Up, up, and away! (the <i>Superman</i> musical)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/660804b-672x372.jpg)

![[July 14, 1964] TO THE MOON, ALICE (the August 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/640714cover-659x372.jpg)