by John Boston

That Low

The uproar at the University of California at Berkeley continues, with student leader Mario Savio becoming instantly famous for his cri de couer: “There's a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious—makes you so sick at heart—that you can't take part. You can't even passively take part. And you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you've got to make it stop. And you've got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it that unless you're free, the machine will be prevented from working at all.”

Ever see that corny old silent movie Metropolis, with its oppressed workers desperately struggling against the gigantic levers of a future civilization’s industry? Do you think Mr. Savio might have had those scenes in mind? Is our culture now to be dominated by the imagery of old science fiction, recycled through late-night TV? It can’t come soon enough for me.

The Issue at Hand

by Michael Arndt

Speaking of retrograde imagery, the January Amazing leads off with what seems a striking misjudgment. Though it features the first installment of a serial by the up-and-coming Roger Zelazny, his longest work to date, the cover is a cartoony though well-executed depiction, by newcomer Michael Arndt, of an extraterrestrial boxer being knocked out of the ring, with a Damon Runyonesque audience looking on, clearly illustrating Blue Boy by the determinedly mediocre Jack Sharkey. Zelazny’s story is relegated to smaller type above the magazine title, with his name hard to read against a bright background. Amazing is clearly leading from the wrong side. (Can’t anybody here play this game?)

He Who Shapes, by Roger Zelazny

by George Schelling

Promising as it seems, I will withhold reading and commenting on Zelazny’s serial He Who Shapes until the concluding installment is at hand, as is my practice. A look at the first few pages indicates that the story involves psychiatric treatment by mental projection—not exactly a new idea (see Peter Phillips’s Dreams Are Sacred from 1948 and John Brunner’s more recent The Whole Man), but not overly familiar either. Zelazny also seems to be making the most of his theatrical background in this one. We will see the results next month.

Blue Boy, by Jack Sharkey

Blue Boy is even worse than I expected. The protagonist, formerly involved in the boxing world, has been drafted, and is sent with a large crew on a mission to Pluto, where they encounter blue-skinned humanoids, whom they clap into the brig, and hastily head back towards Earth. The Plutonians are quite muscular and have a knack for footwork, so our protagonist gets the idea of sneaking onto Earth with one and turning him into a boxer.

by Michael Arndt

That’s about as far as I got (halfway) in this offensively stupid and also interminable screed (34 pages but seems like much more), which is written, and padded, in a stilted and circumlocutory style which seems pretty clearly intended as a pastiche of the above-mentioned Damon Runyon. “Why?” one might cry, but the wind only whispers . . . “one cent a word.” One star. No stars. Heat death of the universe. Cessation of all brain activity. Bring back Robert F. Young!

A Child of Mind, by Norman Spinrad

by Virgil Finlay

We return at least to the semblance of sentience with Norman Spinrad’s A Child of Mind, a clever variation on a stock SF plot. Three guys from Survey land on a planet which seems idyllic, but of course there’s something wrong; there always is. This time, the majority of the females of the various local fauna have cell structures indicating they are really different organisms under the skin.

Turns out they spring from “teleplasm,” an inchoate life form whose modus vivendi is, whenever a male of any species passes by, to discern and produce his ideal mate. Why this all-female survival strategy? As the hero, ecologist Kelton, Socratically explains to one of the other guys:

“Who pays for a wife’s meals?”

“Her husband, of—Oh my God!”

Er . . . that’s not always how it works. If a lioness could speak, she would have a rather different account of things, as would many other females of other species. But never mind, because, of course, very shortly, all three crew members have their own cocoon-grown dream girls: the thuggish one has an adoring slave, the mama’s boy has a sexy mama figure, and well-balanced Kelton has a merely supernaturally beautiful mate who understands his every desire.

This road leads nowhere, of course—to species extinction, since teleplasm doesn’t breed in the usual fashion, and not even to short-term satisfaction for Kelton, to whom

“. . . Woman had always been Mystery.

“And a creature of his own mind could hold no mystery for him, only the unsatisfying illusion of it.”

So Kelton does the only sensible thing, which you can probably guess. While Kelton’s devotion to the autonomy of Woman may be creditable, there are hints of some pretty strange attitudes drifting through the story. At one point, as Kelton is musing about how the teleplasm women are custom-made for their men, he thinks, “Swapping them would be like swapping toothbrushes.” Earlier, Spinrad quotes a “saying among Survey men: ‘Planets are like women. It’s not the ugly ones that are dangerous.’”

Well, let’s reserve the psychoanalysis and give the author credit for a reasonably well-turned story—but meanwhile, Mr. Spinrad, you might think about putting some women on your space crews. Three stars.

The Hard Way, by Robert Rohrer

Robert Rohrer’s growing competence suffers a setback in The Hard Way, a one-set psychodrama starring the sadistic Lieutenant Percy, who is delivering several prisoners from a penitentiary on Earth to one on Mercury. Unfortunately they missed the turn towards Mercury and are heading towards the Sun, to die of heat on the way. May as well have some fun with it! thinks the Lieutenant, and offers the prisoners a choice between slowly roasting to death and opening the airlock for a faster and cleaner exit. Contrived, cliched, scenery-chewing. Two stars, barely, and mainly to distinguish it from the abysmal Sharkey story.

The Handyman, by Leo P. Kelley

by George Schelling

Leo P. Kelley’s The Handyman is a pleasantly inconsequential dystopia about a small town where everything seems pretty nice except for the medical facility, the Hive, which spirits sick people away to its sterile and overlit premises and forbids any medical practice but its own. Old Doc Larkin must ply his profession covertly, masquerading as a handyman and carrying his instruments concealed in a loaf of bread newly baked by his wife. Three stars, also barely.

The Men in the Moon, by Robert Silverberg

by Virgil Finlay

The second of Robert Silverberg’s “Scientific Hoaxes” articles is The Men in the Moon, concerning the hoax perpetrated by journalist Richard Adams Locke, who published a series of articles in the New York Sun concerning the observations of profuse flora, fauna, and people on the Moon, supposedly made by famed astronomer William Herschel from his observatory at Cape Town, South Africa. Herschel was indeed in Cape Town but of course made no such observations and didn’t know Locke was making these claims until years later. Like its predecessor, it’s an interesting story capably told. Three stars.

Summing Up

So: another dose of mediocrity from this historic magazine that hasn’t done much of anything for us lately, and owes us big time, at least those of us putting down good money for it each month. Maybe the Zelazny serial will be its redemption. Hope springs eternal, but it’s getting tired.

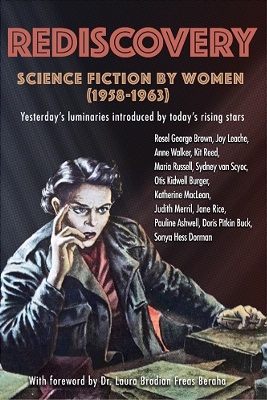

[Holiday season is upon us, and Rediscovery: Science Fiction by Women (1958-1963), on the other hand, contains some of the best science fiction of the Silver Age. And it makes a great present! Think of it as a gift to friends…and the Journey!

![[December 13, 1964] Save us from Yourselves (January 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/641213cover-480x372.jpg)

![[October 12, 1964] Slow Cruising (November 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641010cover-672x372.jpg)