by Gideon Marcus

Dashed hopes

It really looked like it was going to be a happy Halloween. On October 31st, President Johnson made the stunning announcement that he was stopping all bombing in Vietnam. This was in service to the Paris peace talks, which subsequently got a huge shot in the arm: not only were the Soviets on board with the negotiations, but the South Vietnamese indicated that, as long as they had a seat at the table, they were in, too.

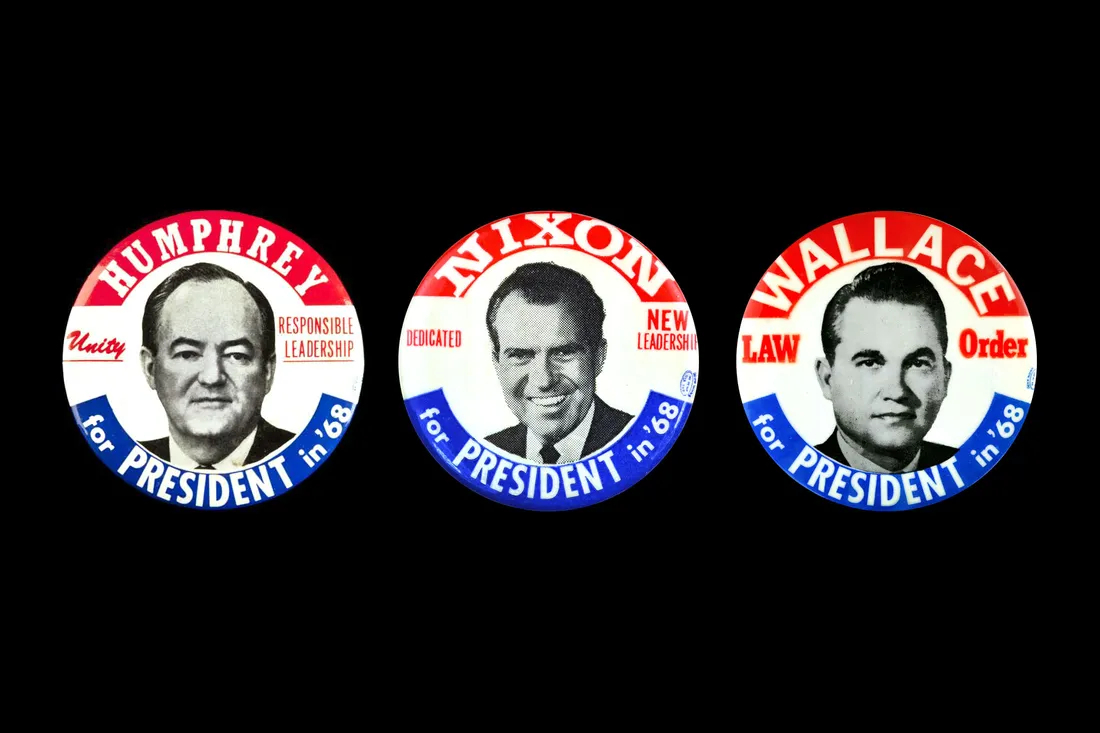

The holiday lasted all of five days. In yesterday's paper, even as folks went to the polls to choose between Herbert Humphrey and Tricky Dixon (or, I suppose, Wacky Wallace), the news was that South Vietnam had pulled out. They didn't like that the Viet Cong, the Communists in Vietnam (as distinguished from the North Vietnamese government), were going to get a representative at the talks. So they're out.

It's not clear how this will affect the election. As of this morning, it was still not certain who had won . Nevertheless, it is clear that Humphrey's chances weren't helped by the derailing of LBJ's peace plans. If a Republican victory is announced, it may well be this turn of events led to the sea change.

Well, don't blame me. My support has always been for that "common, ordinary, simple savior of America's destiny," Mr. Pat Paulsen. After all, he upped his standards—now up yours.

Respite

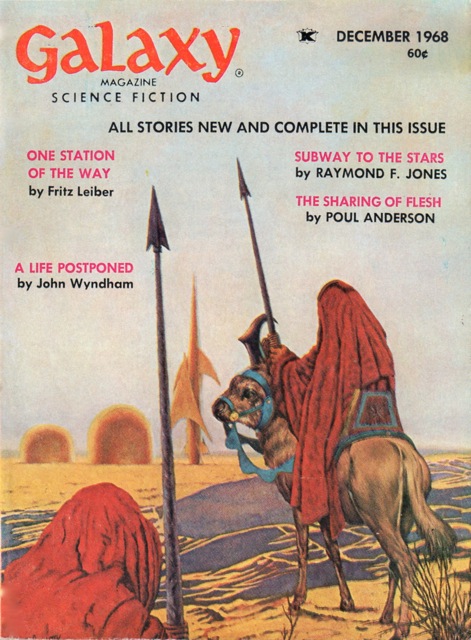

Once again, a tumultuous scene provided the backdrop to my SFnal reading. Did the latest issue of Galaxy prove to be balm or bother? Read on and find out:

by John Pederson Jr. illustrating One Station of the Way

The Sharing of Flesh, by Poul Anderson

by Reese

Evalyth, military director of a mission to a human planet reverted to savagery after the fall of the Empire, watches with horror as her husband is murdered, then butchered by one of the planet's inhabitants. Cannibalism, it turns out, is a way of life here; indeed, it is considered essential to the rite of puberty for males.

The martial Evalyth vows to have her revenge, tracking down the murderer, Mora, and taking him and his family back to their base, where they are subjected to fearsome scientific examinations. But can she go through with executing the killer of her husband? And does Mora's motivation make any difference?

There' s so much to like about this story, from the exploration of the agony of love lost, to the examination of relative morality, to the development of the universe first introduced (to me, anyway) in last year's A Tragedy of Errors. It doesn't hurt that it stars a woman, and women are integral parts of this future society, with none of the denigrating weasel words that preface the introduction of female characters in Anderson's Analog stories (could those be editorial insertions?)

This is Anderson at his best, without his archaicisms, multi-faceted, astronomically interesting, emotionally savvy.

Five stars.

One Station of the Way by Fritz Leiber

by Holly

Three humaniforms watch on cameloids as the star descends in the east. Sure enough, at a home in the east, a divine being prepares to impregnate a local female so that she will bear a divine child.

Heard this story before? There's a reason. But the planet of Finiswar is not Earth, the aliens are not remotely human, and the white and dark duo who pilot the spaceship Inseminator are anything but gods.

An excellent, satirical story. Four stars.

Sweet Dreams, Melissa by Stephen Goldin

A little girl is told a bedtime story about a big computer that stopped doing its job right. That's because the machine couldn't think of casualties and war statistics as simple numbers, battle strategies as abstract puzzles. The problem is its personality; if the computer's mind could be reconciled with its function, the machine could work again. But can any mind be at peace with such a frightful purpose?

A simple piece like this depends mostly on the telling. Luckily, Goldin is up to the task. Four stars.

Subway to the Stars by Raymond F. Jones

by Jack Gaughan

Harry Whiteman is a brilliant engineer with a problem: he's too much of a "free spirit" to keep a job, or a wife. Desperate, when the CIA approaches him about a singular opportunity, he takes it, though the resents being bullied into it.

In deepest, darkest Africa, the Smith Company is working on…something. Ostensibly a mining concern, it produces no gems. On the other hand, whatever it is is important enough that the Soviets have based missiles in a neighboring country—pointed right at the company site!

Whiteman is hired, for his irreverence more than his ability, and begins work as a double-agent. Once on location, he finds the true purpose of the site: it's a switching station of an intergalactic railroad station! But it turns out that the folks at the Smith Company also have multiple agendas…

A mix of Cliff Simak's Here Gather the Stars (Way Station) and Poul Anderson's Door to Anywhere, it is not as successful as either of them. It takes too long to get started, and then it wraps up all too quickly. It's genuinely thrilling as Whiteman peels back the multiple layers of the Smith operation and the factions within it, and when the missiles do find their target, the resultant chaos is compelling, indeed. But then it turns into a quick, SFnal gimmick story better suited to Analog than Galaxy.

I think I would have rather seen Simak takes this one on as a sequel to his novel. Jones just wasn't quite up to it.

Three stars.

For Your Information: The Discovery of the Solar System by Willy Ley

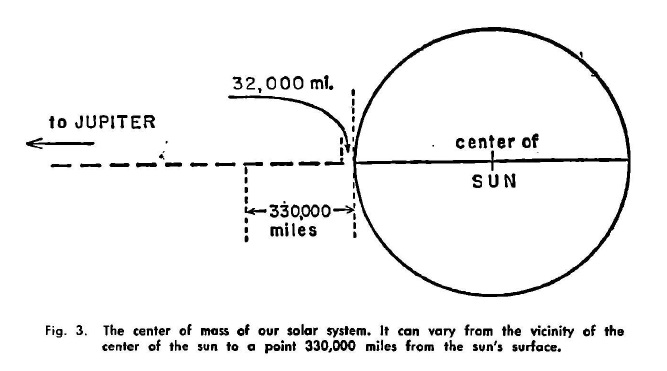

As it turns out, the science article in this month's issue addresses two issues on which I've had keen recent interest. The first is on the subject of solar systems, and if they can be observed around other stars. Ley discusses how the gravity of an unseen companion can cause a telltale wiggle as the star travels through space, since the two objects orbit a common center of gravity (rather than one strictly going around the other).

In the other half of the article, Ley explains how atomic rocket engines work: shooting heated hydrogen out a nozzle as opposed to burning it and shooting out the resultant water out the back end—it is apparently twice as strong a thrust.

What keeps this article from five stars is both pieces are too brief. For the first half, I'd like to know about the stellar companions discovered through astrometry. He mention's Sirius' white dwarf companion, but what about the planets Van de Kamp claims to have discovered around Barnard's Star and so on? As for the atomic article, I'd like to know what missions a nuclear engine can be used for that a conventional rocket cannot.

Four stars.

A Life Postponed by John Wyndham

by Gray Morrow

Girl falls in love with cynical jerk of a boy. Boy decides there's nothing in the world worth sticking around for, so he gets himself put in suspended animation for a century. Girl follows him there. He's still a cynical jerk, but she doesn't care because she loves him. They live happily ever after.

I'm really not sure of the point of this story, nor how it got in this month's issue other than the cachet of the author's name.

Two stars.

Jinn by Joseph Green

It is the year 2050, and aged Professor Morrison, stymied in his attempts to make food from sawdust, is approached by a brilliant young grad student. Said student is brilliant for a reason: he is a Genetically Evolved Newman or "Jinn", with a big brain and bigger ideas. The student has solved Morrison's problem. However, another Jinn wants humanity to go to the stars, and he fears if the race gets a full belly, they'll lose interest.

The conflict turns violent, the point even larger: is there room for baseline homo sapiens in a world of homo superior?

Green doesn't paint a particularly plausible future, but there are some nice touches, and the points raised are interesting ones. I'd say it's a failure as a story but a success as a thought-exercise, if that makes sense.

So, a low three stars.

Spying Season by Mack Reynolds

by Roger Brand

We return, once again, to Reynolds' world of People's Capitalism. It is the late 20th Century, and the Cold War adversaries have reached a more or less peaceful coexistence. The greater challenge is existential: ultramation has taken away most jobs, and the majority of the populace is on the dole. How, then, to avoid stagnation for humanity?

In this installment, Paul Kosloff is an American of Balkan ancestry, one of the few in the United States of the Americas who still has a steady job, in this case, that of teacher. He is tapped by the CIA to go on sabbatical in the Balkan sector of Common-Europe. Ostensibly, his job is not to spy for the USAs, but to sort of soak in the culture of the area over a twelve-month span.

Very quickly, Kosloff finds himself entagled with an underground revolutionary group, with law enforcement, and with several fellows who enjoy sapping him on the back of the head.

Suffice it to say that all questions are answered by the end, the major ones being: why an innocuous pseudo-spy should be a target, why the CIA would send him on a seemingly pointless mission in the first place. In the meantime, you get a bit more history of this world and some tourist-eye view of Yugoslavia. In other words, your typical, middle-of-the-road Reynolds story.

Three stars.

Counting the votes

While not as stellar as last month's issue, the December 1968 Galaxy still offers a more satisfying experience than, well, most anything going on in "the real world". It clocks in at a respectable 3.45, which brings the annual average to 3.23.

Compare that to the 2.81 it scored last year, and given that Galaxy is once again a monthly, I think it's safe to say that, at least in one way, "Happy days are here again."

![[November 6, 1968] Who's the one? (December 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681106cover-471x372.jpg)

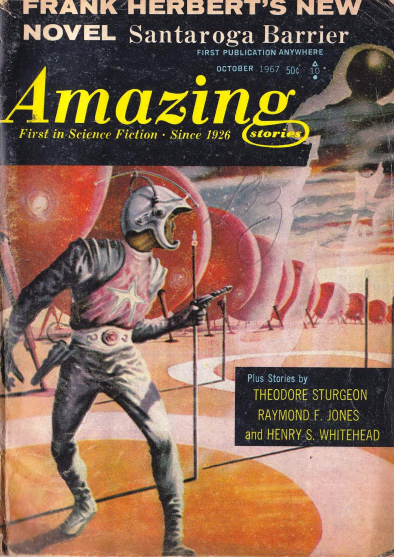

![[September 6, 1967] New Look, New . . . ? (October 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/amz-1067-cover-394x372.png)

![[July 26, 1966] Along for the Ride (<i> This Island Earth</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/this-island-672x372.png)

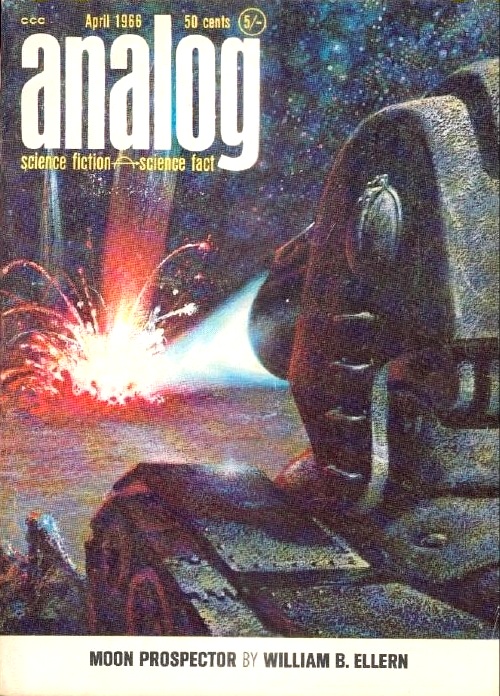

![[March 31, 1966] Shapes of Things (April 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660331cover-500x372.jpg)

![[October 12, 1964] Slow Cruising (November 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641010cover-672x372.jpg)