by John Boston

The Collectors

SF anthologies are not neutral vessels. They are shaped by editors with agendas. Sometimes these are as simple as “what can I throw together to make some money,” but usually they advance the editor’s conception of what the field is, or should be.

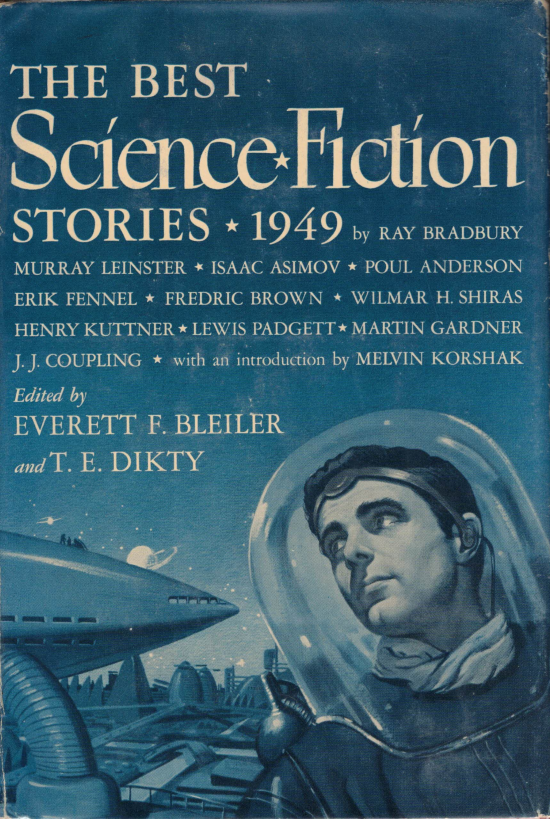

The first “best of the year” compilation in SF was the well-received The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1949, edited by Everett F. Bleiler and T.E. Dikty, published by Frederick Fell in 1949 but containing stories from 1948. The Bleiler-Dikty anthologies spawned a companion series, TheYear’s Best Science Fiction Novels (i.e., novellas), which ran from 1952 through 1954. Bleiler left the project in 1955, to the detriment of its quality, and the series died with a final single volume from Advent, a small specialty publisher, in 1958.

by Frank McCarthy

There was abortive competition along the way. Donald A. Wollheim of Ace Books, a long-time anthologist, published Prize Science Fiction (McBride, 1953), containing 1952 stories supposedly comprising the winners and runners-up for that year’s Jules Verne Prize, an award and a book title that were not heard of again. The next year August Derleth, another veteran anthologist, published Portals of Tomorrow (Rinehart, 1954), collecting stories from 1953 and pointedly subtitled The Best of Science Fiction and Other Fantasy. The editor described it as “covering the entire genre of the fantastic: not only supernatural and science-fiction tales, but also every kind of whimsy and imaginative concept of life in the future or on other planets,” apparently distinguishing it from the Bleiler-Dikty series without mentioning it. There was no second volume.

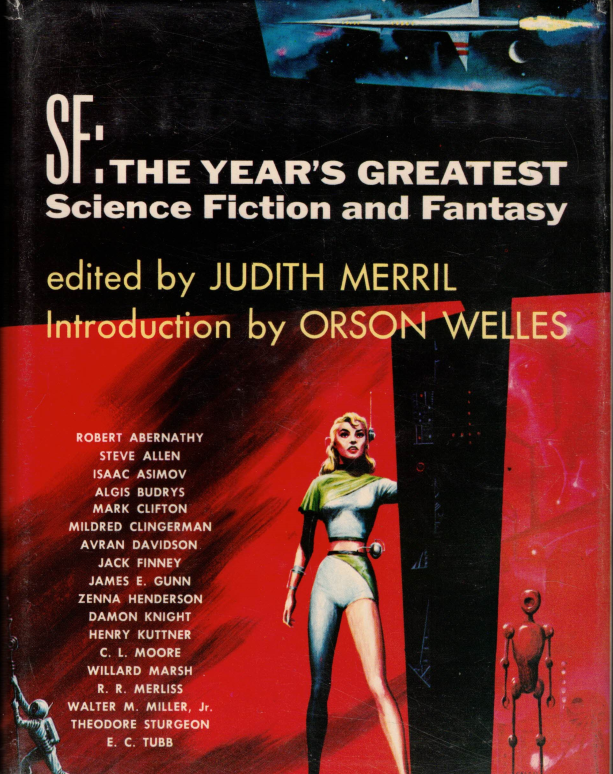

But Judith Merril achieved ignition, and kept it. Her series of annual anthologies shows no signs of flagging after nine years. The first, SF: The Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy, appeared in 1956, with 1955 stories, from the SF specialty publisher Gnome Press, in an unusual publishing arrangement: a Dell paperback edition appeared in newsstands, drugstores, etc., more or less simultaneously with the publication of the Gnome hardcover, rather than after the usual year or so interval before paperback publication. After four volumes, as Gnome tottered towards oblivion, Merril jumped to Simon and Schuster, which published the fifth through ninth books. We await the tenth, slated for December.

by Ed Emshwiller

Merril’s angle from the first was good SF as good literature, accessible to the non-fanatical reader, with emphasis on character—not necessarily character-driven, but more concerned with the perspective and experience of recognizable human individuals than much SF. Her taste in cherry-picking the SF magazines was near-impeccable. She also looked beyond the SF magazines and the writers identified with them.

The latter practice has been both a strength and a weakness, bringing to the SF-reading public many worthy stories that they otherwise would never have heard of, but also including some items that seemed trivial or misplaced but came from a prestigious source or with a prestigious byline. As a result, the Merril series has become woolier and more diffuse in focus over the years. Her last volume included stories from Playboy (two), the Saturday Evening Post, the Saturday Review of Literature, the Peninsula Spectator, The Reporter, and the Atlantic Monthly, and such large literary bylines as Bernard Malamud and Andre Maurois, the latter with a novelette that may have been the best of 1930, when it was first published. Oh, and three cartoons. Of course it also included, as always, a large and solid selection of indisputable SF and fantasy, both from the genre magazines and from other sources.

Merril’s agenda is clear. Let her tell you about it. In her introduction to the last of the Gnome volumes, she wrote:

“The name of this book is SF.

“SF is an abbreviation for Science Fiction (or Science Fantasy). Science Fiction (or Science Fantasy) is really an abbreviation too. Here are some of the things it stands for. . . .

“S is for Science, Space, Satellites, Starships, and Solar exploring; also for Semantics and Sociology, Satire, Spoofing, Suspense, and good old Serendipity. . . .

“F is for Fantasy, Fiction and Fable, Folklore, Fairy-tale and Farce; also for Fission and Fusion; for Firmament, Fireball, Future and Forecast; for Fate and Free-will; Figuring, Fact-seeking, and Fancy-free.

“Mix well. The result is SF, or Speculative Fun.”

English translation, if you need one: What she thinks the SF field is, or should be is . . . not really a field. That is, not categorically distinguishable in any clear-cut way from the general body of literature, though having a somewhat different set of preoccupations than the typical contemporary novel or short story.

You can debate her argument, but I’m not inclined to. I think if Merril did not exist it would be necessary to invent her, or someone similar, to help rescue the field (that word again!) from excessive insularity. I am also glad to have her book to read each year, exasperating as some of its contents may be.

Yin and Yang

But not everyone feels that way, and it is not surprising that there is once again some competition. Donald Wollheim is back for a second try, with co-editor Terry Carr, a long-time SF fan and shorter-time author now working at Ace Books, with that publisher’s World’s Best Science Fiction: 1965, a chunky original paperback with a distinct “back to basics” air about it, though there’s no comment at all about Merril’s book and nothing that can be read as a disguised dig at it.

So what’s the more overt angle, besides “here are some stories we think are good”? First, the title does not include “Fantasy,” a word which for Merril covers a multitude of exogamies. And the “World’s Best” in the title is not ceremonial; the editors make much of having scoured the world, and not just the US, for stories. The back cover says “Selected from the pages of every magazine regularly publishing science-fiction and fantasy stories in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, Australia, and the rest of the world. . . .” The yield: five non-US stories, of seventeen in the book. Two of these are from the British New Worlds, which is not exactly news, but the others are from less familiar sources, though they are closer to the Anglo-American genre core than some of Merril’s catches.

First of these three is Vampires Ltd., by Josef Nesvadba, a Czech psychiatrist and well-known SF writer, the title story of his recent collection, about the current preoccupation with fast automobiles; the protagonist accidentally gets his hands on an especially fine one, and per the title, finds out that it doesn’t really run on gasoline. We reach that denouement by way of a surreal and hectic series of events which makes little pretense to plausibility. But that is beside the author’s point, which is satire. It’s an interesting look at a different notion of storytelling than you will find in the US SF magazines. The Weather in the Underground, by Colin Free, best known for his work for the Australian Broadcasting Commission, from the Australian magazine Squire, is more consistent with US conventions. It takes place in an underground habitat where part of humanity has fled for safety, leaving the rest to freeze in a new ice age. This life is made tolerable by constantly renewed psychological conditioning, but our protagonist’s conditioning never quite took hold, so he’s miserable and maladjusted, leading to banishment and a sorry end. It’s a strikingly vehement story, very tightly written and forceful, and one of the best in the book.

The third non-US/UK offering is What Happened to Sergeant Masuro?, by Harry Mulisch, from The Busy Bee Review: New Writing from the Netherlands. Mulisch is apparently a notable Dutch literary figure, with eight books published. Sergeant Masuro was a soldier in a Dutch patrol in Papua New Guinea; one of the other soldiers raped a native girl, or tried to; the headman was later seen skulking around; and Sergeant Masuro began to undergo a terrible transformation. The story is the report to headquarters by the patrol’s superior officer, who recounts both the events and his own anguish at some length. Amusingly, the plot—white men go into the jungle, transgress against the natives, and are cursed—is a long-familiar pulp plot of which dozens of examples could no doubt be exhumed from Weird Tales, Jungle Stories, and the like. The literary gloss doesn’t add much to it.

Aside from these foreign trophies, the book is a stiff gust of de gustibus. Of the five stories which one of us at Galactic Journey thought worthy of five stars (excluding several outright fantasies from Fantastic), none are included. Nor are any included from our longer end-of-the-year Galactic Stars list. Of the stories that are in the book, only two were awarded four stars, and one—Leiber’s When the Change-Winds Blow—fled the wrath of Gideon with only one star.

And much of what is here is remarkably pedestrian or worse. The editors seem determined to reproduce the genre’s weaknesses as well as its strengths. Starting the book is Tom Purdom’s Greenplace, which features such lively matters as a psychedelic drug and a man in a wheelchair being beaten by a mob, but is essentially an extremely contrived and implausible warning about a genuine problem: how democracy can survive, or not, as psychological manipulation becomes more sophisticated. Next, and proceeding downhill, Ben Bova and Myron R. Lewis’s Men of Good Will is an equally implausible, but more trivial, story built around a scientific gimmick that’s not even entirely original (remember Jerome Bixby’s The Holes Around Mars?).

This is followed by Bill for Delivery, by that faithful purveyor of contrived yard goods Christopher Anvil, about the problems some salt-of-the-earth spacemen have carrying a cargo of unruly and dangerous birds from one star system to another. At this point, a reader who bought the book thinking it was time to check out this “science fiction” stuff people are talking about would probably start to think “How can anybody possibly be interested in this?” and toss it or leave it on the bus.

There’s more of this ilk later on: C.C. MacApp’s weak and gimmicky For Every Action, and Robert Lory’s The Star Party, an annoyingly slick rendition of an original but silly idea. And Leiber’s When the Change-Winds Blow answers the question that hardly anyone is asking: “What does a talented author do when he can’t think of anything of substance to write?”

But that’s the bad news. The good news is a number of worthwhile stories. Four Brands of Impossible by new writer Norman Kagan is at once an amusing picture of aspiring math and science brains in their element, and a chilling one of the uses to which their talents may be put, wrapped around an interesting mathematical idea. William F. Temple’s A Niche in Time is a smart time travel story that goes off in an unexpected direction. John Brunner’s The Last Lonely Man (one of the New Worlds items) develops a clever piece of psychological technology in the author’s earnest and methodical way. Edward Jesby, another new writer, contributes the stylish and incisive Sea Wrack, which starts out as a tale of the idle and decadent rich in a far future where some humans have been modified to live undersea, and and turns into a story of class struggle, no less.

Philip K. Dick’s Oh, To Be a Blobel! is a sort of slapstick black comedy updating Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. Thomas M. Disch’s Now Is Forever is a sharp if overlong piece of sociologizing about the effects of wide availability of matter duplicators, which kick the props from under everyone’s getting-and-spending way of life. New writer Jack B. Lawson’s The Competitors is a breezy rearrangement of stock SF elements that reads to me like a facile parody of the genre, probably done with A.E. van Vogt in mind.

To my taste the most striking item here is Edward Mackin’s New Worlds story The Unremembered, a sort of religious fantasy framed in SF terms. In the automated and urbanized future, lives have been extended for hundreds of years, but the show seems to be closing from sheer ennui: the birth rate is falling and the youth suicide rate is rising, and older people are queueing up at the euthanasia clinics. Apparitions of people are appearing and disappearing seemingly randomly, because (it is hinted) the human span has become divorced from its natural length. The elderly protagonist becomes one of the apparitions, and his consciousness takes a Stapledonian journey through the cosmos before arriving at the final revelation. C.S. Lewis would appreciate this one if he were still around. It is quite different from anything I’ve seen from Mackin before, or from anybody else for that matter.

But that’s the only really strikingly memorable story here; closest runners-up are the Colin Free and Edward Jesby stories, based mainly on their intensity in presenting relatively familiar sorts of material. The writers who are pushing the SF envelope in notable ways are not here—no Lafferty, no Zelazny, no Ellison, no Cordwainer Smith. And there is too much overt dross.

So, the bottom line: a pretty decent book with much solid material, but it mostly fails the “Surprise me!” test. Maybe the next one will be more startling. Meanwhile, Merril will be back to argue with in a few more months.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[June 12, 1965] The Number of the Bests](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/wollheim-cover-382x372.png)

![[May 8, 1964] Rough Patch (June 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640508cover-672x372.jpg)