by Victoria Silverwolf

Monsieur Verne and Mister Wells at the Movies

A decade ago, Walt Disney Productions had a big hit on their hands with their cinematic adaptation of the famous Jules Verne novel 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. It was popular with both audiences and critics, winning Academy Awards for Art Direction and Special Effects. It was a lovely film, full of charming details combining futuristic technology with aesthetics of the past.

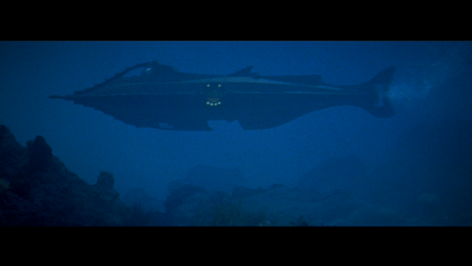

The super-submarine Nautilus; a thing of beauty.

The super-submarine Nautilus; a thing of beauty.

The success of this nostalgic science fiction adventure led to a number of Verne adaptations. Most notable was Around the World in 80 Days, a lush, big budget production notable for the number of Hollywood stars who made cameo appearances.

Old Blue Eyes in a tiny role as a piano player.

Old Blue Eyes in a tiny role as a piano player.

Since then we've had enjoyable films taken from the French author of Extraordinary Voyages, including Journey to the Center of the Earth, Master of the World, and Mysterious Island, all reviewed here at Galactic Journey. A couple of lesser Verne adaptations, namely Valley of the Dragons and Five Weeks in a Balloon, did not escape the acid pen of our local critics. There was also From the Earth to the Moon, which somehow managed to slip under the radar of our Galactic Journeyers. This was a handsomely filmed, if rather dull, account of an American munitions manufacturer (Joseph Cotton) using a powerful explosive to send a spaceship to the Moon just after the Civil War.

Blast off!

Not to be outdone, H. G. Wells, the British master of Scientific Romances, came to the big screen not too long ago in the George Pal production of The War of the Worlds, another Oscar winner for Best Special Effects.

A Martian war machine on the prowl for Earthlings.

Although this version of the story updated the setting to modern times, Pal returned to the Nineteenth Century with an even more highly regarded Wells adaptation, The Time Machine, which won kudos from our host.

With the exception of The War of the Worlds, what these films have in common is the fact that they take place in the Victorian Era. For lack of a better term, we might refer to this sub-genre of fantastic cinema as Steam Science Fiction. I was recently able to attend a secret sneak preview of the latest offering of this kind, already released in the United Kingdom, and due to appear in American theaters later this year. Watch for the trailer the next time you're at your local cinema.

Fly Me to the Moon; Or, A Trip to the Moon on Gossamer Wings

In Dynamation and LunaColor, no less.

First Men in the Moon is directed by Nathan Juran, a veteran of science fiction films, both good (20 Million Miles to Earth) and not so good (The Brain from Planet Arous.) The screenplay for this British production comes from the combined pens of Nigel Kneale (best known to SF fans across the pond for his television serials The Quatermass Experiment and Quatermass II) and Jan Read, who contributed to the delightful fantasy film Jason and the Argonauts.

Don't forget, it's in, not on.

We begin in the near future, as an international team of astronauts land on the Moon. They find a Union Jack and a note claiming the satellite in the name of Queen Victoria.

A mystery!

The note happens to be written on the back of a legal contract mentioning the name Katherine Callender. Investigation leads to the discovery of Arnold Bedford, the man Miss Callender married long ago, now nearly a century old. He tells his incredible story, and we go into a long flashback, firmly in the land of Steam Science Fiction.

Martha Hyer and Edward Judd as the two Victorian lovebirds.

In 1899, our happy couple encounter Joseph Cavor, an eccentric scientist who creates a substance that deflects gravity. Having a healthy ego, he names the stuff Cavorite. As if that were not enough, he plans to use it to launch a spaceship on a lunar voyage.

Lionel Jeffries as the inventor.

Arnold agrees to go to the Moon with Cavor, which seems like a rash decision for a man about to be married. Through a series of unforeseen circumstances, Katherine winds up accidentally accompanying them; you know how much trouble women are! The unlikely trio winds up on the surface of Earth's satellite after a particularly rough landing.

The charming little spaceship approaches its target.

Katherine is left behind, no doubt to prepare tea and crumpets, while the two men don diving suits and set out to explore this strange new world.

Things really get interesting when our heroes fall down a shaft and wind up inside the Moon, justifying the title. It seems that the interior is inhabited by insect-like, sentient beings, whom Cavor dubs Selenites. The plot, mostly played for light comedy up to this point, takes a more serious turn when Arnold, panicking at the sight of the aliens, attacks and kills several of them. The two men escape back to the surface, only to discover that the Selenites have dragged their spaceship, and the woman inside it, underground.

A Selenite, brought to life through the magic of Dynamation.

What follows is a fast-moving adventure, as the intrepid pair explore the city of the Selenites in search of Katherine, battle a huge, caterpillar-like monster, and encounter the Grand Lunar, ruler of the Selenites. An interesting aspect of the story is the contrast between Cavor, the man of science, who wants to exchange knowledge with the Selenites, and Arnold, the man of action, who believes they pose a threat to humanity.

What good is a science fiction thriller without a huge monster?

The Grand Lunar, not at all happy about human aggressiveness.

An ironic ending brings us back to the near future, as we find out what happened to the three explorers and the Selenites.

Adding greatly to the film's appeal is the outstanding stop-motion animation of Ray Harryhausen. The eerie and imaginative world inside the Moon excites the viewer's sense of wonder, and the Victorian design of Cavor's spaceship provides a great deal of charm. You might have to be a little bit patient with the relaxed pace of the opening scenes, but the result is well worth the wait.

Four stars.

As we enter a new era of space exploration, with the very real possibility that a human being will stand on the surface of the Moon within a decade, it's fitting that we look back on those who imagined the future and wrote about it. I hope that more Steam Science Fiction movies appear in theaters in the days to come, and that we never forget the dreamers of yesteryear.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[July 26, 1964] Yesterday's Tomorrows (<i>First Men in the Moon</i> and Other Steam Science Fiction Movies)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/first-men-in-the-moon-trailer-title.jpg?resize=640%2C272)