[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

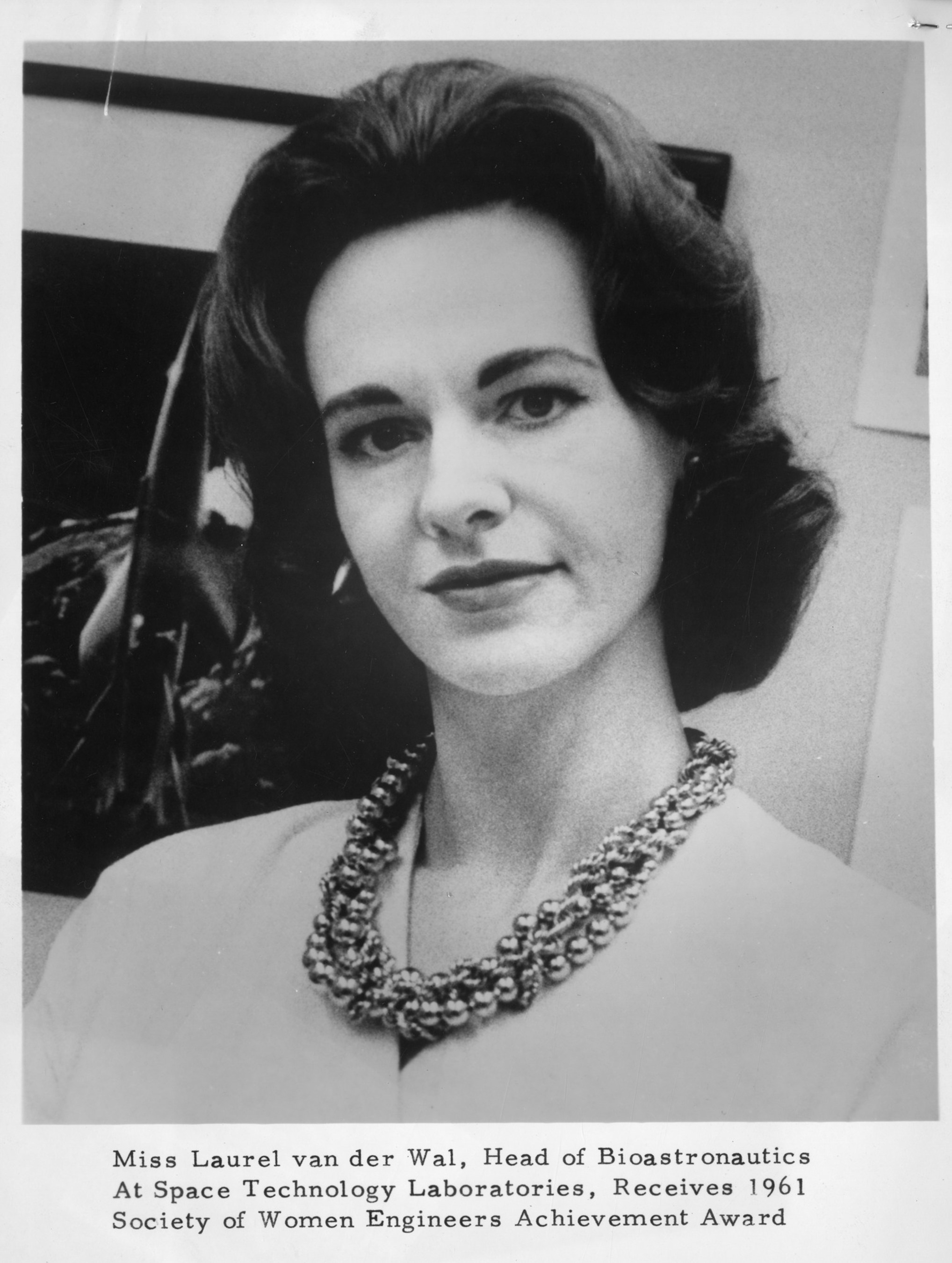

by Gideon Marcus

Halloween is normally a time for scares — for us to invoke, dress up as, and tell stories of various ghosts, ghoulies, and goblins. But let's face it. We've had quite enough fright for one month, what with the Free and the Communist worlds just seconds from Midnight over the Soviet placement of nuclear missiles in Cuba. Thankfully, that crisis has been resolved peacefully, with the Russians agreeing to dismantle their weapons and return them home (who knows what unreported concessions we may have made to assure that outcome). Nevertheless, with our heart rates still elevated, I think the best remedy is to skip terror this time around and focus on the things that make us smile:

Candy and space missions!

Niña and Pinta sail the magnetic oceans

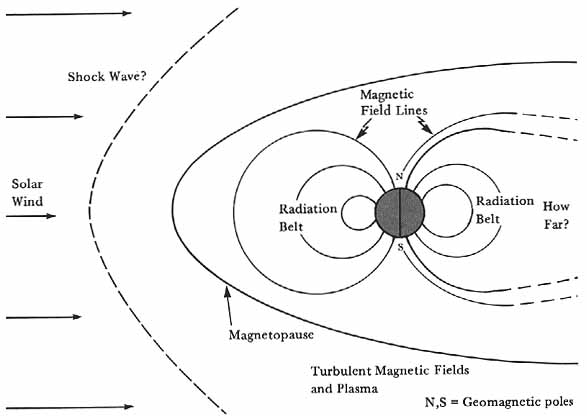

Last year, I gushed rhapsodically about the voyage of Explorer 12, a vessel designed to map the contours of the Earth's magnetic field. The results did not disappoint; thanks to that little probe's journey, we now know that there is a sharp boundary between the our planet's magnetosphere and the magnetic emanations of our sun. This, then, is the map of our unseen ocean, as of this year:

But how constant is this border, this magnetopause, between ours and the solar magnetic sea? What are the mechanisms of its flow? Moreover, what of the three charged "Van Allen" belts girdling the Earth? And what impacts do our atmospheric atomic tests have on them, short and long-term?

That's the nature of science. Early experiments tend to provide more questions than answers! Explorer 12, which ceased operations in late '61, won't be answering any more of them; however, NASA launched two more Explorers just this month to pick up where the magnetic Santa Maria left off.

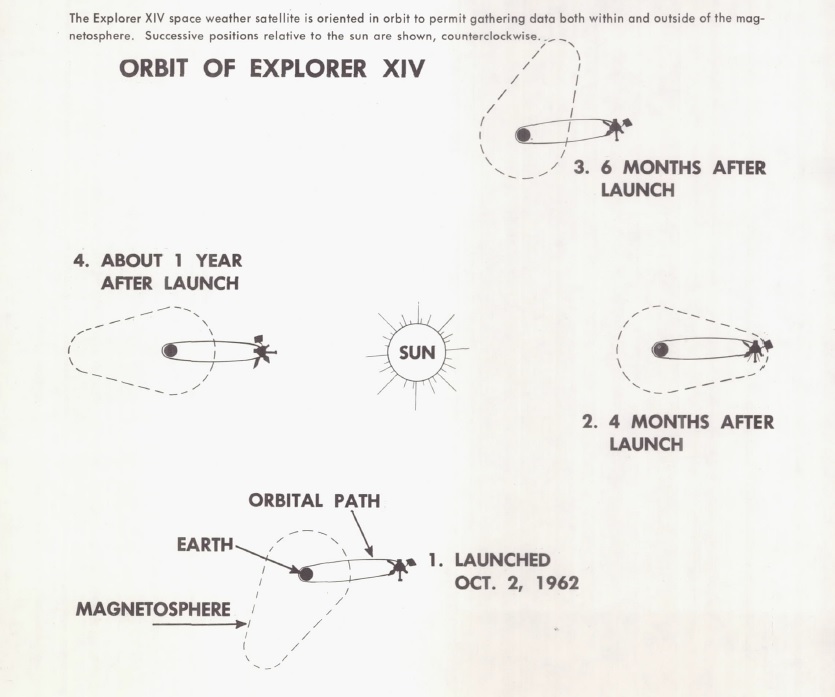

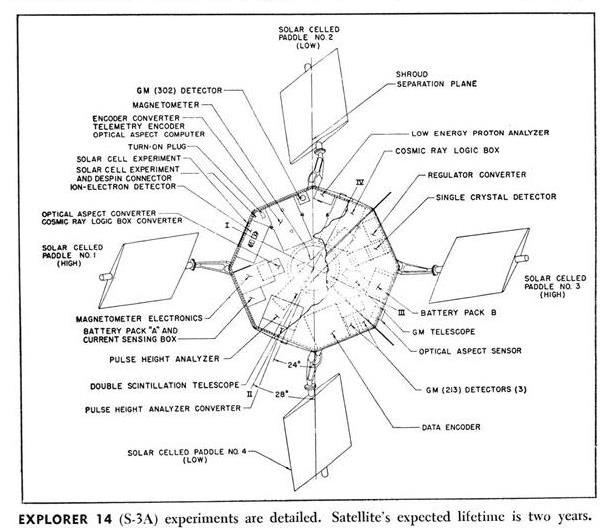

Explorer 14 was launched October 2. Like Explorer 12, it has a highly eccentric orbit in which the 89 pound spacecraft zooms 60,000 miles into the sky before flying near the Earth. This takes the probe through all of the layers of the Earth's magnetic field. The experiment load is largely the same as Explorer 12's, with a couple of additional sensors.

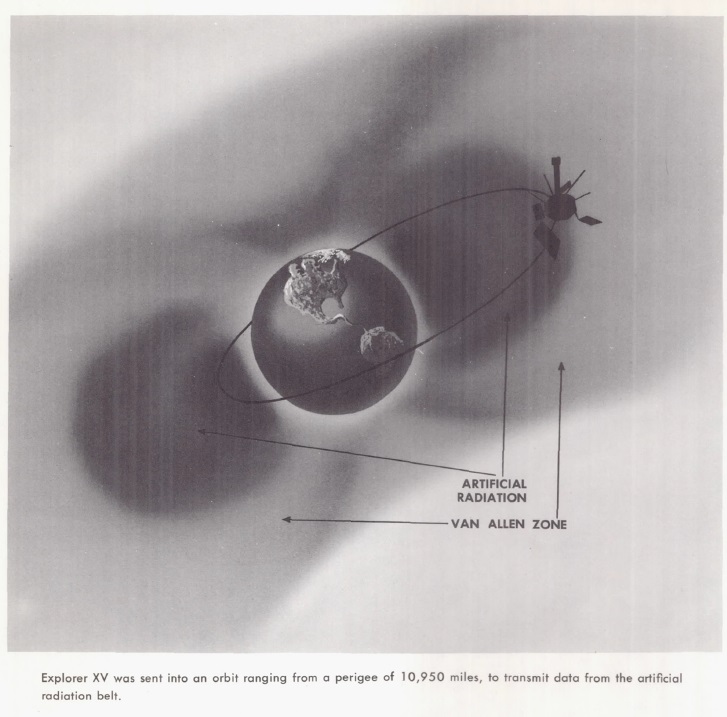

Explorer 15 is a different kind of ship. It only goes up to about 10,000 miles, and its mission is more focused on the artificial particle fields created as the result of nuclear explosions. Unfortunately, when the spacecraft launched on October 27, it did not extend its "arms" — little weight-bearing spars — to slow down the spin imparted to it by its rocket. Like an ice skater with her arms tucked in, Explorer 15 is spinning much faster than intended. Nevertheless, good data is being gotten from five of its seven experiments.

Watch this space for exciting updates. Between the new Explorer twins and the Venus probe, Mariner 2, now several million miles from Earth, the age of space magnetic exploration is truly underway!

Chocolate Arms Race

Since early this century, two superpowers have faced off, each developing a physical and sociological arsenal designed to sway the world into one's camp or the other's. I am not speaking of the mortal struggle between Communism and Democracy…but that of Pennsylvania's Hershey Company versus Minnesota's Mars, Incorporated.

On the one side, we have the eponymous Hershey Bar, the conical Hershey's Kisses, the peanut-infused Mr. Goodbar, the rice-included Krackel, etc. On the other, the Milky Way bar, the Three Musketeers Bar, and most importantly (at least to this column's editor) the peanutty Snickers Bar.

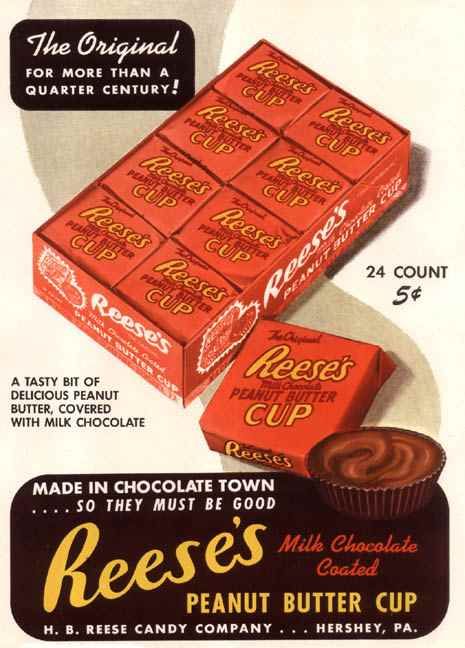

Of course, this oversimplifies things. There are plenty of "Third World" candy makers, including Nestle's (Crunch), Necco (Clark Bar), and Peter Paul (Mounds and Almond Joy). In fact, my favorite chocolate-based candy is Reese's Peanut Butter Cups, made by Harry Burnett Reese Candy Co. Harry died six years ago, but I think we can trust his six sons to carry on the independent tradition that has made these confections so delicious.

In fact, I wholeheartedly support greater parity among the world's chocolatiers. After all, we've just seen what crises can result in a bipolar world…

Canada joins the Space Race!

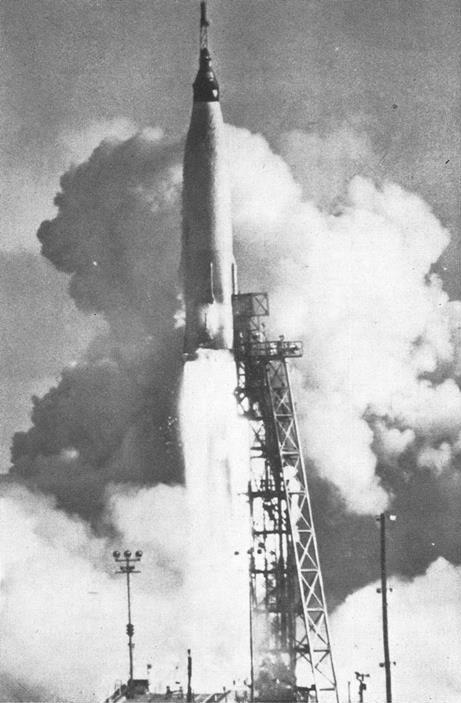

Typically, a Thor Agena B launch from Southern California means yet another Air Force "Discoverer" spy sat has gone up; such flights are now weekly occurrences. But the flight that went up September 29 actually carried a civilian payload into polar orbit: Alouette 1, the first Canadian satellite.

Alouette is designed to study the ionosphere, that charged layer of the atmosphere hundreds of miles up. But unlike the sounding rockets routinely sent into the zone, Alouette will survey (or "sound") the ionosphere from above. Canada is particularly interested in understanding how and when the sun disrupts the region, interrupting radio communications. Our neighbor to the north is a big country, after all, and it is the Northern Hemisphere's first line of defense against Soviet missiles and bombers. Radio is, therefore, vital to both defense and civilian interests.

According to early data, it looks like the highest "F2" layer of the ionosphere is as reflective to radio waves from the top as the bottom. Alouette has also, by beaming multiple frequencies down to Earth, helped scientists determine what radio wavelengths aren't blocked by the ionosphere.

Sometime next year, Alouette will be joined by an United States "sounder" mission with a different experiment load. Then we'll have two sets of space-based data to corroborate with ground-based measurements. Soon, one of the more mysterious layers of the atmosphere, one completely unknown to us a century ago, will be well understood.

Sweetly Sour

Some people love chocolate. Strike that — most people love chocolate. But I tend to favor fruit-flavored candies. For instance, Smarties, Pixy Stix, the recent Starbust Fruit Chews, and brand new for this year: Lemonheads!

Made by Ferrara, the same folks who make Red Hots (which I also love), Lemonheads are a delicious hard candy mix of sour on the outside, sweet on the inside. I have now made myself sick at least twice on these things, and I firmly intend to do so at least twice more. I'm an adult, and no one can stop me. Besides — it keeps me away from Candy Corn…

The Moon claims another Victim

Speaking of sour…first it was the three Air Force Pioneer missions launched in 1958 – none of them made it even halfway to the Moon. Then the four Atlas Able Pioneer missions of 1959-60 didn't even got into Earth orbit. Now five out of five Ranger probes launched over the last year have failed.

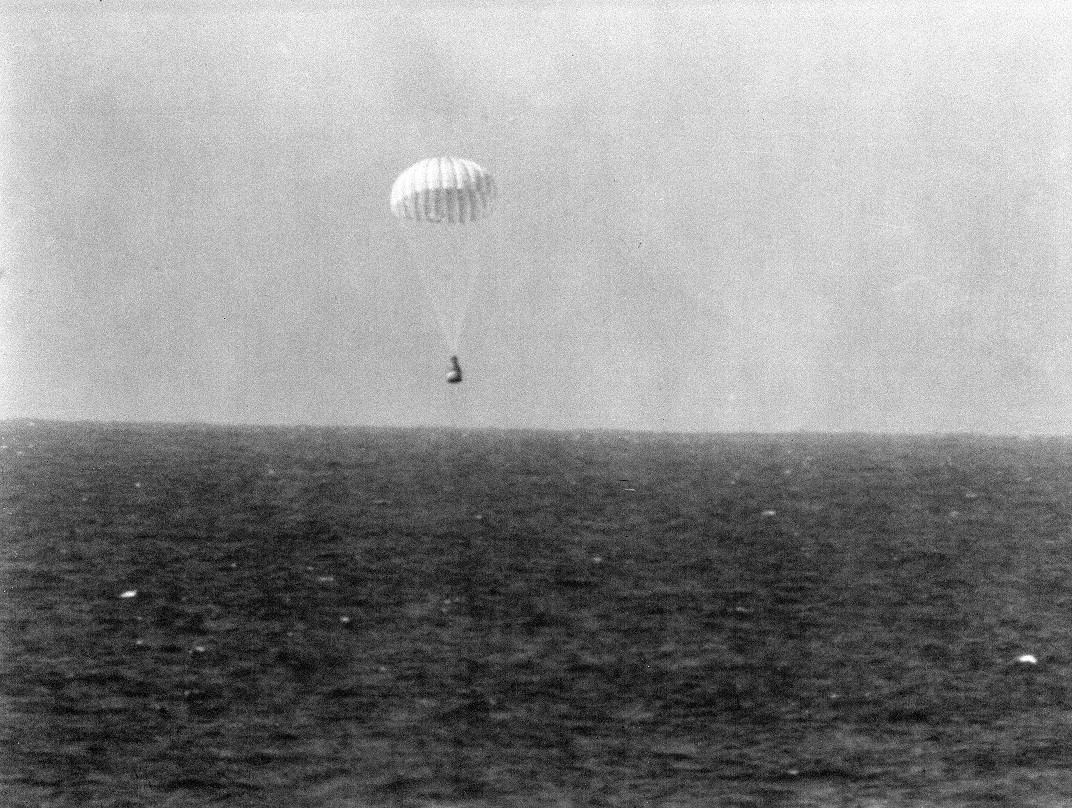

Launched October 17, the fifth of the Rangers went on the fritz just a few hours after take-off. On the way to the Moon, the solar power transformer went kaput, leaving the spacecraft on battery power, which rapidly depleted. Two days later, the silent ship sailed 9,000 miles over the surface of the Moon, after which ground-based 'scopes quickly lost sight of it.

Ranger 5 marked the last of the "Block II" line. The two Block I spacecraft were supposed to stay in Earth orbit and do sky science, but neither of them lasted long enough. None of the three Block IIs succeeded in their mission of smacking the Moon with their bulbous noses, filled with sensor equipment. I suspect NASA is going to do a lot of work making sure the Block III craft, armed with cameras, reach their destination alive and snapping photos. That is, if Congress doesn't cut their funding.

Happy Halloween, and don't let the news get you down.