by Gideon Marcus

Time for the Stars

I was having a lovely conversation with fellow traveler Kris about the mixed reviews for the British anthology show, Out of the Unknown. Some critics are saying the stories aired would have been better served in a conventional setting rather than on Mars or wherever.

Indeed, this has been a common complaint for decades, that science fiction should be uniquely SF with stories that depend on some kind of scientific difference/unique setting, even if many of the trappings are familiar.

Galaxy is a magazine that has led this charge since its inception in 1950 and it therefore comes as no surprise that this month's issue features a myriad of settings that are in no way conventional, backdrops for stories that could take place in no genre but science fiction.

Citizens of the Galaxy

by John Pederson, Jr.

The Mercurymen, by C. C. MacApp

On the face of things, Mercury would seem a most inhospitable planet for colonization. Until this year, the general conception of things was that the innermost planet of our solar system was tidally locked, presenting just one baked hemisphere eternally toward the sun, while the other remained in perpetual frigid night.

by Gray Morrow

C. C. MacApp offers up a most imaginative tale set on this half-cooked world. The planet, or at least the twilight zone between the hot and cold sides, is overrun with the vines of a plant, the interiors of which are large enough and contain sufficient air and water to support human inhabitants. How they plant came about or how the settlers came to dwell in them is a mystery, but hundreds of years later, the colonists have reverted to near savagery. The ecosystem of the vines provides most of their needs: latex for vacuum suits, luminescent mold for light, oxygen-producing fungus for air. But for precious metals and for new soil for crops, the denizens must venture into the airless waste outside.

Similarly, population pressure periodically forces tribes to split, members of a certain age tasked to form a new settlement further along the vine. The Mercurymen is the tale of Lem, eldest son of a recently expired chief, who leads a party out over the bleak landscape of Mercury in search of a new hope. Along the way, he must deal with a deadly environment, hostile tribes, and treachery within the group.

Because so many of the concepts are alien, even as the characters are human, The Mercurymen can occasionally be a detailed, hard read. Nevertheless, I appreciated MacApp's world building quite a lot, and I was carried along with Lem on his engaging, difficult adventure. The novella would merit expansion into full length novel though the following discovery may require a complete change in setting to make it work:

From Nature, Volume 208, Issue 5008, pp. 375 (October 1965):

Rotation Period of the Planet Mercury, by McGovern, W. E.

The recent radar measurements of Mercury indicate that the period of rotation of the planet is 59 +/- 5 days1. This result is in complete disagreement with the previously quoted value of 88 days based on the visual observations of the markings on Mercury2-6. In this communication we show that the same visual observations can not only be reconciled with the radar-determined rotation period of Mercury but, in addition, can be used to derive an improved value for the period of rotation of the planet, namely, 58.4 +/- 0.4 days.

Yes, Mercury isn't tidally locked at all, and the stories that made use of this presumption are now all obsolete. Editor Pohl may even have known this even when he put this issue to bed, as the news first broke in June.

Still, it's a good story, and again, you can squint your eyes and pretend it takes place on a different one-face world entirely.

Three stars.

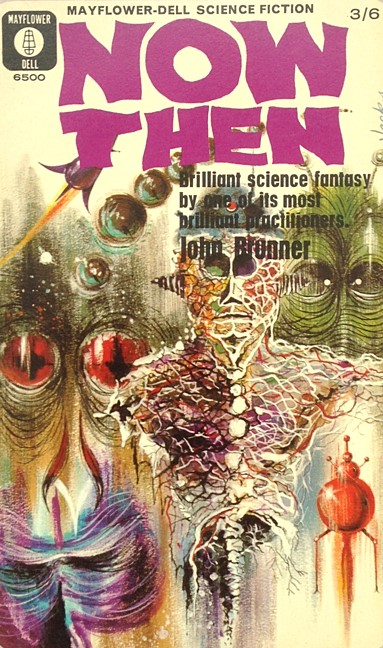

Galactic Consumer Reports No. 1: Inexpensive Time Machines, by John Brunner

The latest Galaxy non-fact article is written in the style of the venerable magazine Consumer Reports, offering evaluation of six cut-rate personal time machines.

The aforementioned Kris noted that there seem to be two John Brunners: one who writes Hugo-worthy material like The Whole Man and Listen! The Stars… and another who churns out hackwork. I'd say this piece is representative of a third Brunner, neither outstanding nor unworthy. It's a cute piece, although I would have appreciated a little more time travel in it.

Three stars.

Laugh Along With Franz, by Norman Kagan

by John Giunta

In a disaffected future, "None of the Above" (the so-called "Kafka" vote) threatens to become the electoral candidate of choice.

More pastiche of outlandish societal explorations than tale, I found myself falling asleep every few pages. I'm afraid Norm Kagan continues not to do it for me.

One star.

For Your Information: The Healthfull Aromatick Herbe, by Willy Ley

A rather defensive Willy Ley discusses the history of tobacco in his latest science article. It's actually pretty interesting, though I am no closer to taking up the still-ubiquitous pasttime than I was before.

Four stars.

The Warriors of Light, by Robert Silverberg

by Jack Gaughan

In the previously published story, Blue Fire, Silverberg introduced us to an Earth of the late 21st Century, one that worships the Vorster cult. Vorster and his disciples cloak the scientific pursuit of immortality with a bunch of religious mumbo jumbo, complete with a rosary of the wavelengths of light.

Warriors of Light is not a sequel to Blue Fire, per se. Instead, it is a story from a completely different perspective, that of an initiate of Vorsterianism who is recruited by a heretical group to steal some of the cult's deepest serets.

Reportedly, Silverbob produces 50,000 words of salable material per week, enough to make it seem like SF is his full time career even though it's just a fraction of his overall output. Light is not the brilliant piece that its predecessor was, but the Cobalt-90 worshipping future Earth remains an intriguing setting, and I look forward to the next story that takes place therein.

Three stars.

"Repent, Harlequin!" Said the Ticktockman, by Harlan Ellison

In Ellison's latest tale, The Master Timekeeper, a.k.a. the Ticktockman, is the arbiter of justice for a chronologically regulated humanity. Everything runs to schedule; tardiness is punishable by the lost of years from one's lifespan. There is no room for deviation, nonconformity.

Yet one clownish fellow, known as The Harlequin, cannot be restrained. His antics distract, his capers disrupt, his personality compells. This dangerous threat must be stopped. But in erasing the heretic, can even the master inquisitor escape just a little of the nonconformist contagion?

This is the most symbolic of Ellison's work to date, and with a deliberate, almost juvenile storytelling aspect that veers toward the Vonnegutian. I appreciate what Harlan is doing here, but there's a lack of subtlety, a ham-handedness that makes the piece less effective than much of his other work.

Oh, my telephone is ringing. One moment.

Ah. Harlan says I'm an ignorant so-and-so and if I withdrew my head from my seat, I might be able to better comprehend his work. (Note: this is not an exact transliteration).

Anyway, three stars.

The Age of the Pussyfoot (Part 2 of 3), by Frederik Pohl

by Wallace Wood

Last up is the continuation of last month's serial by editor Pohl, who is indulging himself in his first love, writing. Forrester, who died in the late 1960s only to be ressurrected in the 25th Century when medical technology was up to the task, has run out of dough and has become employed by the one boss who will have him, an alien from Sirius, member of a race with whom Earth is currently in a Cold War.

In this installment, we learn about how this state of not-quite conflict came to be, as well as about the Forgotten Men, the penniless humans who make a living outside of normal society. We also learn how difficult it is to survive when one cannot pay the bill on one's "joymaker," the ubiquitous hand-held combination telephone, personal computer, and electronic valet.

Let us hope that we never get so reliant on this kind of technology that we find ourselves similarly helpless without them!

Pussyfoot continues to be entertaining and imaginative, far more effective in execution of its subject than similarly themed Kagan piece, though less satirical in its second installment than its first.

Four stars.

Beyond This Horizon

My Heinlein motif for the article section titles may be a little misplaced given that R.A.H. doesn't appear in the pages of Galaxy this month. Call it artistic license since his most recent novels are coming out (or have come out) in sister mags Worlds of Tomorrow and IF.

Anyway, at the very least, the stories in the December 1965 Galaxy hold to the Heinlein tradition of fundamentally incorporating unique settings. No transplanted Westerns or soap operas here!

For the most part, it works, resulting in a solid 3-star issue. Why don't you pick up a copy, Space Cadet, and see if you agree!

![[November 10, 1965] Strangers in Strange Lands (December 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/651110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 6, 1965] Turns, Turns, Turns (Avalon Hill's <i>Midway</i> and <i>Battle of the Bulge</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2020-03-08-12.49.20-672x372.jpg)

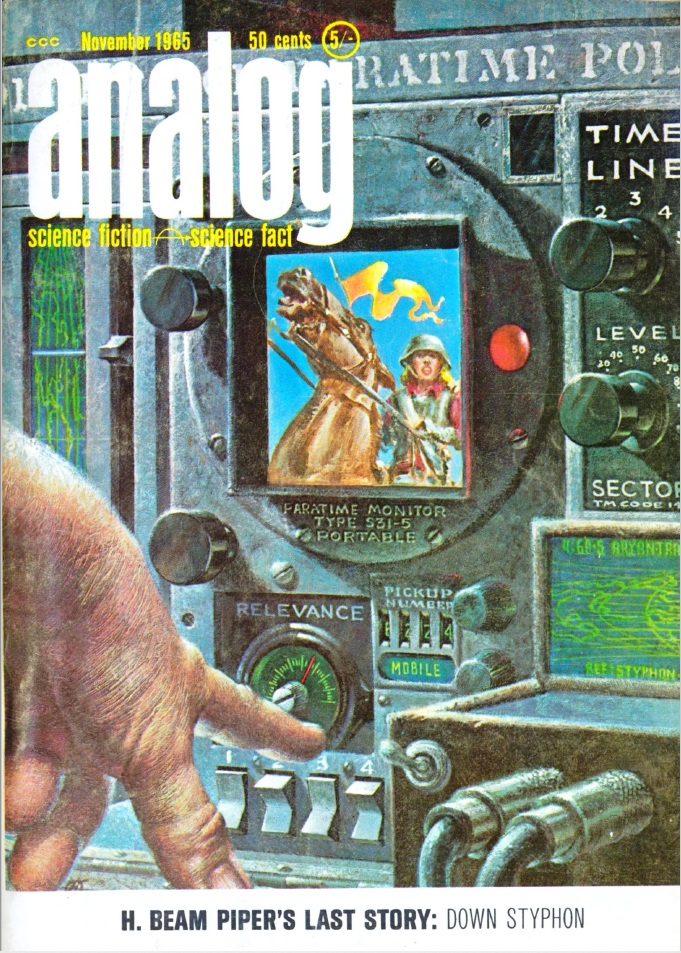

![[October 31, 1965] Finished and Unfinished Business (November 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651031cover-672x372.jpg)

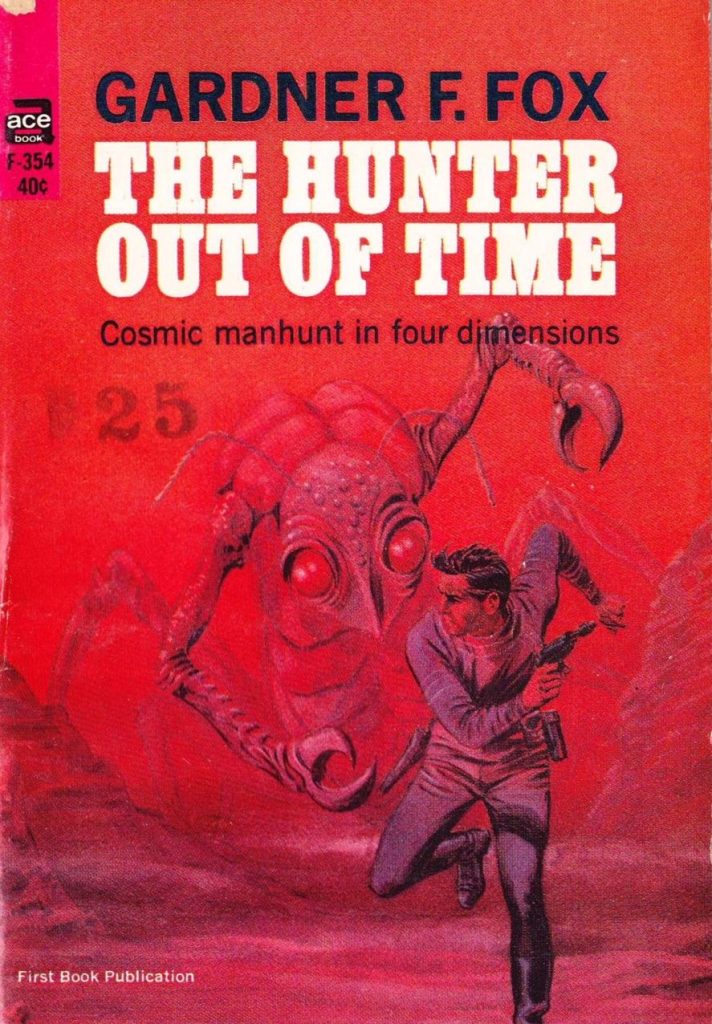

![[October 24, 1965] "What time is it?" (October Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651024covers-1-672x372.jpg)

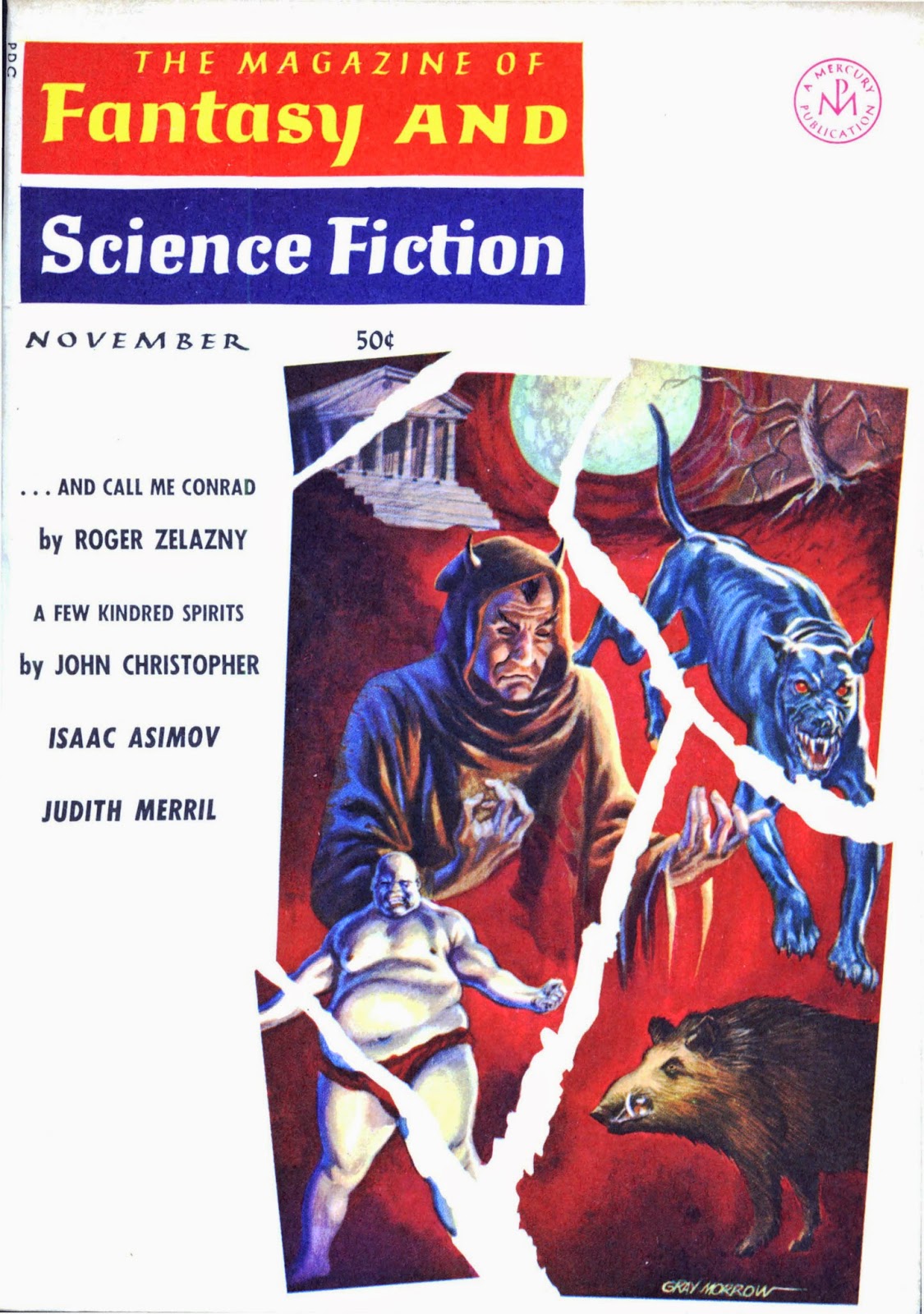

![[October 18, 1965] Turn, Turn, Turn (November 1965 <i>Fantasy & Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651018cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 8, 1965] Handle with Care (<i>Forbidden Planet</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651010a-672x372.jpg)

![[September 30, 1965] Big and Little Bangs (October 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650930cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 20, 1965] Unfinished Business (October <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650920cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 14, 1965] The Face is Familiar (October 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650914cover-551x372.jpg)

![[August 26, 1965] Stag Party (September 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/650828cover-396x372.jpg)